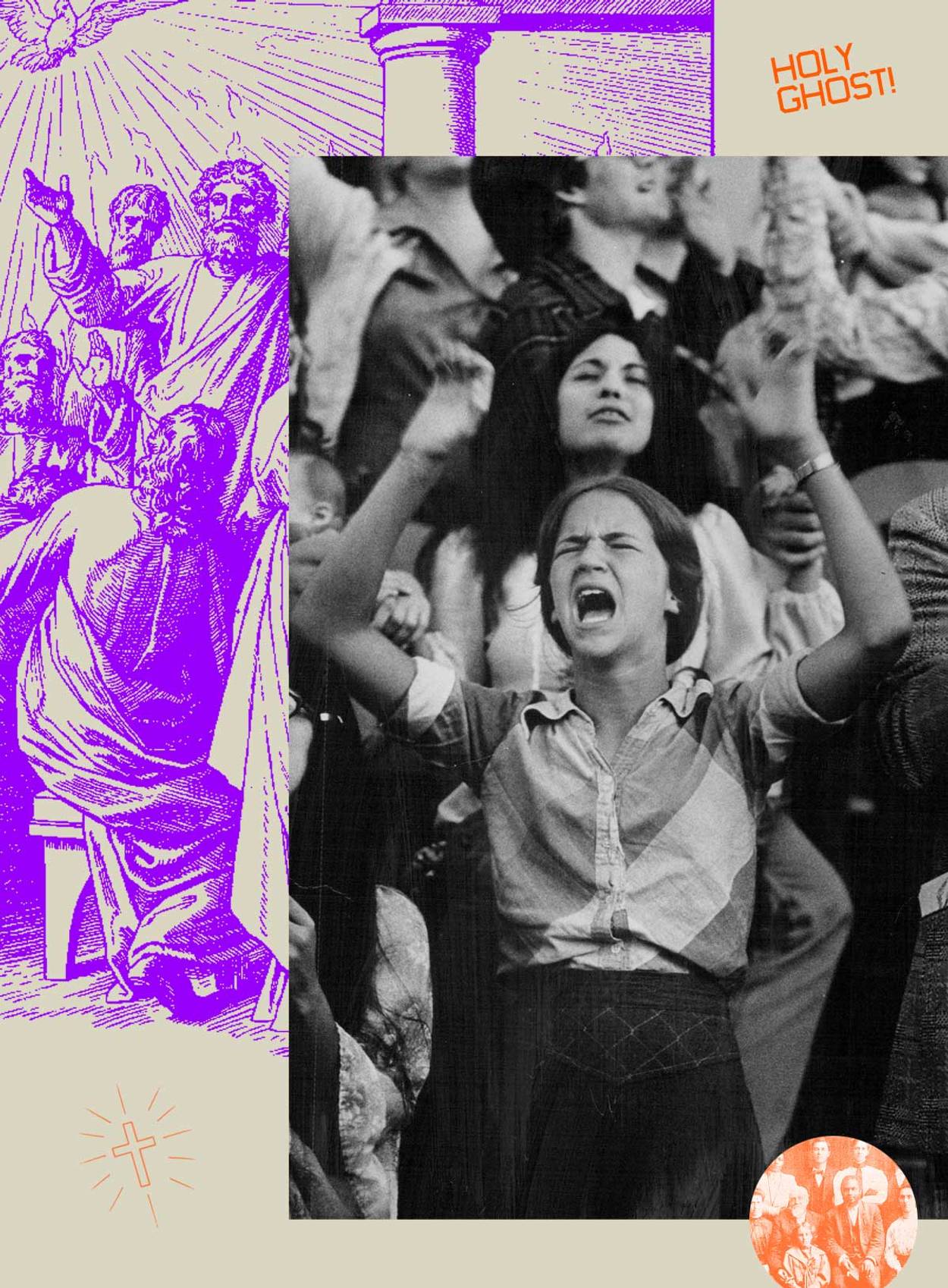

When FX released The Secrets of Hillsong in May, the much-discussed TV docuseries presented a tale that is all too familiar in a fallen, post-Tammy Faye Bakker world: At Hillsong, a New York City megachurch, a charismatic rock-star celebrity pastor falls from grace as he succumbs to the worldly temptations of sex, money, influence, and power. Early in the series, the church’s denominational affiliation with what one talking head describes as “old-school Pentecostalism” gets a fleeting mention amid a montage of grainy, dated-looking footage of ecstatic worshippers shown speaking in tongues and singing with their hands in the air, eyes closed. “They’re a little extreme,” says another with a laugh. The documentary, which takes pains to show the lack of diversity—whether of sexuality, gender, or race—at Hillsong New York City, overlooks the vibrant ferment that gave birth to Pentecostalism itself, as well as a spirituality developing in some quarters of the faith today that is at once self-critical and outward looking.

Pentecostalism, a faith characterized by lively prayer services that can include speaking in tongues and impassioned preaching, is a comparatively recent Christian denomination. It began in the 19th century, with the parallel development throughout the Anglosphere of a grassroots spiritual enthusiasm grounded in personal experience. Its theology is rooted in history both ancient and more contemporary: a key event in the Christian Bible’s Book of the Acts of the Apostles, as well as the theology of John Wesley, who is recognized as the father of Methodism. In the U.S., its catalyst is usually identified as a religious revival movement that began in Los Angeles in 1906; over a century later, it still enjoys a widespread presence in the U.S., and is a rapidly growing global phenomenon.

Whereas Assemblies of God and Church of God in Christ are two major homegrown American churches that exist under the Pentecostal umbrella, Hillsong, which originated in Australia, is something of a parvenu in the American religious ecosystem. But its New York City campus, established in 2010, was the first of what would grow to 16 stateside franchises at its peak (nine of them folded in a matter of weeks last year, due to a series of scandals). At various points, Hillsong’s American branch counted Justin Bieber and other notables as members. The ambassador for a cool, accessible Christianity in its heyday—de-emphasizing (while quietly maintaining traditional beliefs in) many controversial cultural issues—Hillsong represented a kind of coming full circle for Pentecostalism: It marked an acceptance into both the secular and Christian mainstream, and with its influential powerhouse music catalog and bleeding-edge style and branding, the ability to set the tone for other Pentecostal and nondenominational churches around the country.

Although not quite the poster child for contemporary American Pentecostalism, Hillsong and its vestigial influence remains a useful starting point for an exploration of the denomination. It is “one of Australia’s greatest exports,” according to Mark Fennell, a documentarian and former Hillsong member, speaking in a recent interview in his native Australia. “It should go like: iron ore, Hemsworth brothers, Hillsong.” Fennell, who produced a documentary on Pentecostalism and Hillsong in Australia, grew up in Pentecostalist churches, including Hillsong, before stepping back from Christianity altogether as a young adult.

Although no longer a believer, when speaking about the motivation for his Pentecostalism documentary, The Kingdom, Fennell addresses what he perceives as a shortcoming of many religion documentaries. “There’s no shortage of documentaries about Pentecostal Christianity, and particularly Hillsong, particularly at the moment,” he said with a laugh. But when negative media stories began to appear about Hillsong in the late 1990s and early 2000s in Australia, something bothered him. “The thing you saw on TV was legitimate. Like, there were real concerns about you know, money, and you know, coercive behavior. I think those things are really important to talk about. But the world that you saw on those news reports, and it’s true now, bore little resemblance to the thing that people rocked up to on Sunday,” Fennell said. “You know whenever you see stories about churches, it’s like, you can tell—you can kind of tell that sitting underneath it, is this little thing of like, ‘Look at them. They’re freaks!’” But as someone who still has loved ones in Pentecostalism and retains positive associations with aspects of the community he experienced, he is interested in showing that two things can be true at once. “It’s not a monolithic faith,” he said. And in the case of Hillsong in particular, which was and is renowned for its concert arena production values and atmosphere at services, “Beyond just saying, ‘oh, they’ve got good music and nice lights,’ there’s something else there, right? And I think that’s the other thing that when, you know, stories about Hillsong are done, it always kind of comes back to the same ideas of you know, bright lights and music, the same power chords, and I think that misses a trick. Because that’s part of it, no doubt, but there’s something else there that keeps people, and you have to examine that.”

It’s that “something else” that the FX documentary, in its mission to highlight Hillsong NYC’s ethical, legal, and moral failings, is less at liberty to explore. And the Hillsong brand is perhaps more closely popularly associated with Pentecostalism in its native Australia, whereas the NYC branch featured in the FX series wore its affiliation very lightly—almost imperceptibly. But the experiential aspects of worship at Hillsong, the bright lights and the power chords, are distinctly Pentecostal. And while the Hillsong brand is once again the period main character in American pop culture discourse, as it is every so often when a new documentary or podcast about it comes out, another closely related aspect of Pentecostal worship is enjoying one of its occasional moments of cultural prominence: revival.

Perhaps the earliest instances of widespread religious fervor in American history were the First and Second Great Awakenings of the 18th and 19th centuries. But more recently, a multiday revival at Asbury University in Kentucky made headlines for attracting hundreds of worshipers singing and praying together for days without pause.

It wasn’t Asbury’s first revival. The university’s founder, John Wesley Hughes, had belonged to the Wesleyan-Holiness movement, a spirituality rooted in intense personal experience that would go on to inspire the Azusa Street Revival in Los Angeles in 1906. This revival would become what is known today as Pentecostalism.

The Book of the Acts of the Apostles describes a divine visit, 50 days after Passover, of spiritual encouragement paid to Christ’s committed disciples after his crucifixion. Unsure of what awaited them from either Temple or Roman authorities as followers of the recently executed Jesus, they were gathered together in hiding. Acts paints a vivid scene of the Holy Spirit—the third “person” in the Trinity, which Christians believe to be a powerful manifestation of the relationship between Christ and God—descending on these members of the early Christian church, in the form of flames, or “tongues of fire.” These flames in turn inspire the assembled gathering to begin speaking about their faith in various foreign languages, thus enabling them to be understood by visitors from around the Middle East, gathered in Jerusalem for Pentecost.

Pentecost is the “birthday of the church” in some understandings of the event, seen as a reversal of the Tower of Babel story found in Genesis, in which God divides the peoples of the world by language. For Christians, Pentecost forms a crucial understanding of what their faith is all about. The way that emphasis on the Pentecost story is exhibited, however, can vary widely.

A Canadian and professor of Pentecostal theology at Evangel University in Springfield, Missouri, Martin Mittelstadt said that even though he identifies “a certain kind of American elitism that wants to believe that all routes go back to the Azusa Street Revival,” he contends that the 1906 Azusa event “shapes immensely kind of the DNA of the movement,” he said, making it “the symbol of early Pentecostalism.”

Mittelstadt said that John Wesley inaugurated a back-to-basics spirituality that made him a “precursor” to Pentecostalism in the Anglosphere. Wesley’s strong belief in personal conversion experiences and what he called “entire personal sanctification” meant for him, and those he would influence, that human proclivities like desire, ambition, and love could all be made holy. “In the late 19th century, there arrived this language of ‘baptism in the spirit,’” Mittelstadt said, which evolved into a belief that personal holiness meant constant recommitment to God, even after one’s initial conversion; like the apostles in the Book of Acts, professed Christians could be enabled, through their openness to an ongoing outpouring of grace, to plug into God’s holy spirit, and operate intimately within it. Miraculous results were practically taken for granted.

The holiness movement was in some ways a reaction against a skeptical culture that celebrated the rational. Even in Christian circles, cessationism, the belief that miracles had ceased with the time of the first Apostles, was taking hold. Early-20th-century Pentecostalists, then, were riding a counterwave against the cumulative societal effects of the Enlightenment and Industrial Revolution: Spiritualism also gained traction in the late 19th century, along with an interest in alternative medicine and healing, as a significant number of people militated against this mindset.

In America in particular, Mittelstadt said, the proto-Pentecostal holiness movement propagated by Wesley was very popular in 19th-century African American spirituality, “The deep sense of groaning and longing and lament and hope,” he said, “they desperately needed more than a cognitive response for Christianity to work, they needed experience.” Wesleyanism is not the only strand of influence on Pentecostalism as a global movement, he said, but as it developed in the United States, it was key. Pentecostals and those who emphasized a baptism of the holy spirit did not have a copyright on holiness, but Wesley’s conception of it provided a familiar common language.

The culminating result was that by the early 20th century, when the Azusa Street Revival began, it was led by an African American Methodist, William Seymour.

The men and women who gathered to this particular revival in Los Angeles were participating in a widespread phenomenon that had rolled over from the 19th century to become what David Cole, professor of Pentecostal and charismatic movements at The King’s University in Southlake, Texas, said was “one of the real fountainheads of the Pentecostal movement.”

Cole described the Azusa Street Revival, which lasted through 1908, and was characterized by multiple daily services and the novel practice of worshippers speaking in tongues (unlike in the Book of Acts, these tongues were not necessarily existing languages spoken elsewhere, but might be unknown even to the speaker), as an ecumenical affair. Men and women, various races, different socioeconomic classes and even faiths, all came together in an old African Methodist Episcopalian church building on Azusa Street to pray. Seymour oversaw not only the prayer meetings, but the dissemination of a newsletter about their burgeoning movement that boasted a circulation of 50,000.

It was “a democratization of the faith,” Cole said, that was to go by the wayside as different strains of Pentecostalism emerged in the decades that followed Azusa. Liturgical and mainline denominations with more social influence distanced themselves from this style of what is called “charismatic” worship, which would in turn lead to a desire for recognition and respectability in certain corners of the upstart denomination.

By the mid-20th century, some Pentecostals had begun aligning with the evangelical movement. “They wanted to be accepted as real Christians in the larger culture,” Cole said. They began to de-emphasize what he calls “their Pentecostal distinctives,” downplaying speaking in tongues, healing, and prophecy to become “evangelical-plus.” By the 1980s and ’90s, this strategy synced with what was known as “the seeker-sensitive movement” in evangelicalism, he said, an effort “to attract as many unchurched people as possible.” That meant not leading with the distinctives and holding off on getting into specifics, in order to prioritize simply sharing the gospel. New York Times opinion writer David French has described evangelicalism to Tablet previously as less of a coherent ideology and “more of an exit poll category,” usually functioning as a catchall phrase to describe a broad set of spiritual, social, and often political beliefs. Prominent religious research group Barna distinguishes evangelicals in part by the primacy that their Christian belief takes in their lives, as well as their personal responsibility to share their faith with others. “They wanted to have a more broad reach in the culture for people that don’t know anything about Pentecostalism,” said Cole, “but they might be interested in trying a cool church that had good music.”

A quick tour of Pentecostal worship in the Bible Belt in 2023 reveals that both the traditional revival-style of Pentecostal worship, as well as the seeker-sensitive model exemplified by Hillsong’s American churches (“Hillsong is a Pentecostal church,” says a former NYC congregant in the docuseries. “Most people probably wouldn’t know that, might be surprised to find out.”), are alive and well.

At one recent streaming service I watched on the Facebook page for New Life Tabernacle United Pentecostal Church in Aberdeen, North Carolina, “Holy Ghost!” was a frequent intonation, along with “Hallelujah!” as a worship team (singers, a keyboard, and a drum kit) repeated a hymn with the reiterative lyrics, “I am a child of God.”

Congregation members of different ages and races came up to the altar and knelt or prostrated themselves as hymns were sung, others singing along with the words that appeared overhead on a projector screen, hands in the air and their eyes closed. Hymns were punctuated by spoken prayers, with indeterminate tongues heard periodically, indistinct vocalizations that overlapped in the din of fervent shouted prayer and singing. The pastor, a tall, suited man named Jonathan Scarboro, was up on the pulpit one moment, encouraging his congregation, the next he was down among members of the congregation, praying with them.

Scarboro’s wife, Meme, is the worship leader who oversees the music, which she acknowledges is integral to the service, but not ultimately essential. There have been services, she said, where she has even stopped the music to better enable worship, which she contends is something distinct from praise. “Praise,” she said in a phone interview, is “more outward,” whereas worship comes from a place of “deep reverence.” On the whole, however, at a Pentecostal church, “people are more outward in their worship.” Ultimately, Scarboro said, “it all comes down to love of God.”

The word “Gather” appears in large letters at the front of the church. It is, according to a sermon posted on April 16, “a prophetic word” that was not chosen for the church’s theme for 2023 at random, but revealed to the congregation through prayer and discernment.

“This is a year of gather,” said the preacher, a younger man named Will Bell, in his sermon to the enthusiastic congregation. “This is the year that people are coming home. This is the year that they’re going to walk through the doors.”

Bell told the congregants that the church has received phone calls from people who have not previously attended the church, “they don’t even know what church it is,” but that they feel like they’re supposed to attend.

“It is not the Lord’s will that revival not happen,” he said.

He then shifted his focus, to the need for those already within the fold to recommit to their distinctively animated style of worship, noting that singing and dancing are commanded in the Psalms that exhort believers to engage in praise and worship. “It is biblical that you clap your hands,” he said as the keyboard begins to vamp in anticipation of the praise team. “It is biblical that you dance, it is biblical that you leap.” Praise, he said, “will get you through a lot of things.”

At another, more seeker-friendly congregation nearby, the pastor said in a recent streaming service (he declined to be interviewed for this piece) that he comes from a Church of God background (Church of God is a Pentecostal denomination). There is no mention of Pentecostalism on their website or social media, and everything from the location to the pastor’s trendy outfit is aimed at a younger, likely less “churched” demographic. Nevertheless, the distinctly charismatic style of worship on display marks it as Pentecostal.

“Common in today’s Christianity is, again, the frustration with the Church and with denominations, that you’ve got these new churches starting, they don’t even want the label Pentecostal,” Mittelstadt said. “So they’ve got this kind of Starbucks church idea or coffee shop idea, everybody’s welcome, we’re not going to preach at you. It’s more of a seeker emphasis.” In a shift from the seeker-friendly churches of the ’80s and ’90s, many such congregations “are actually re-evangelizing their own,” he said. “Their mission is those who were formerly churched.”

Scarboro said this is another motivator behind the continued streaming of their church’s services long after COVID restrictions lifted, as well as this year’s emphasis on “Gather.” It’s because of “right now,” she said, when in addition to unchurched seekers, New Life is aiming to draw in those “that used to be part of the church.” It is bearing fruit, she said, attracting young people that include the children of congregants, now seeking an alternative to the experiences offered by the world, what she calls “shallow emotion.”

“Though they don’t want to adhere to the language, they’re still on the same kind of quest,” said Mittelstadt of many Pentecostals today. In the wake of scandals in churches like Hillsong and elsewhere, “They’re not returning to rational Christianity. They want experience, but they want authentic experience that’s going to make a difference in every part of their daily lives, and that’s been the disconnect that 21st-century Christians are experiencing.”

Mittelstadt speaks of an exodus as Pentecostals who, like Christians in other denominations, are disillusioned with their church leadership. Cole attributes disaffection among Pentecostals in part to the drive for respectability that came about in the mid-20th century. As faiths become institutionalized, he said, ossification and routinization can follow. Respectability can breed elitism and insularity, resulting in a faith “more upper middle class than you wanted to be.” A far cry from the raucously integrated democratic mélange of Azusa Street.

Indeed, to the extent that some within Pentecostalism become involved with democracy, it is in a decidedly secular form. The Secrets of Hillsong features prominent Pentecostals, including Hillsong founder Brian Houston, meeting with Donald Trump, and underscores the conservative politics of many within the denomination.

For clergy, who must take care about propounding politics from the pulpit, nevertheless, “the cord between their political side and the gospel,” said Mittelstadt, “it’s not even separable.” Although as a Canadian, he was aware of the way that politics and religion overlap in America, living in Springfield, Missouri. “You can’t imagine it until you live in it,” he said. “It is so un-Western European and Canadian.”

All the same, he said placing Pentecostals politically is “tricky.” As a multiracial denomination, political affiliation is hard to generalize. “It definitely leans right,” he said, while noting there are nuances; white Pentecostals likely tend to vote Republican due to views on sexual ethics, and although Black Pentecostals tend to share their white co-religionists’ views on abortion and LGBTQ issues, they may bring an additional concern for social justice issues that flavors their politics differently.

And despite their interracial beginnings over a century ago, in 2023, Pentecostal worship is not always integrated. Suburban churches tend to be dominated by white congregants, he said, but cities like LA, Portland, and Kansas City tend to be more diverse, with members from Black, white, Asian, and Latin American communities.

For all that, beginning in the 1960s, a development in and among liturgical Christian denominations began a process of ecumenism that continues to this day.

It was then, in Van Nuys, California, that an Episcopalian priest named Dennis Bennett was going to some Pentecostal prayer groups and “had some experiences where he experienced gifts of the Holy Spirit,” Cole said, “speaking in tongues and prophesying, and praying for healing and that kind of thing.” It was something he felt he needed to share with his congregation. Although asked by church leadership to step back from ministry, Bennett gained mainstream media attention, and was relocated to a parish in Seattle, where he became a charismatic Episcopal pastor, and a model for liturgical faiths who were having what Cole calls “charismatic experiences” within their denominations.

Presbyterians, Methodists, Baptists, Lutherans, and Catholics were following suit within various smaller prayer groups and Bible studies. “It became a charismatic movement that was transdenominational,” Cole said, “similar to the Pentecostal movement back in the early 20th century, which sort of shook up existing denominations at that time.”

In the past 20 years, Cole said that Pentecostal cooperative bodies like the Pentecostal World Fellowship are formally engaging with Catholics, Lutherans, Methodists, and Presbyterians in ecumenical conversations at the international, national, and local levels.

Over roughly the same period, Cole said, Pentecostals have “started to accept the fact that they really need to be part of the larger church, that they need to recognize that there are real Christians in non-Pentecostal churches.” As Christian churches, including more established churches, began to incorporate a Pentecostal style of worship, the assumption in many Pentecostal circles was that they would join their churches. But as more people started prioritizing experiential worship and incorporating it into their theology, Cole said, “It really has forced the Pentecostal movement to figure out, OK, how do we contribute to this larger body of Christ, whoever they may be, and wherever they may worship?”

Mittelstadt is part of a three-year process of formal Catholic-Pentecostal dialogue that finishes this September. Academics had been doing it independently for a while, he said, but official meetings under the aegises of the U.S. Council of Catholic Bishops and the Pentecostal Charismatic Churches of North America are something new. “In terms of ecumenism, the goal is always to find common unity and common witness,” he said. “And I think Catholics and Pentecostals share a lot—we’re experiential religions,” Mittelstadt said, “We’re Christians that value encounter. We’re magical religions. The [Catholic] sacrament [of Communion] is enchanted.”

As a member of a faith that openly embraces the experiential, Mittelstadt doesn’t perceive a threat to his worldview when someone likens a Taylor Swift singalong in the West Village to the recent Asbury revival. He cites another Taylor: “I think that’s what Charles Taylor would say, is this desire for an encounter, that something’s bigger than me,” he said. “I think it’s innate, and after 150 years of Enlightenment, of telling people to suppress it, people are saying, ‘no.’ But at the same time, the church has lost a lot of credibility,” alluding to some of the same institutional shortcomings identified by Fennell.

Scarboro cautions that this search for what Taylor and Mittelstadt might call “enchantment” is not the intrinsic goal of Pentecostal worship as she understands it. “We would be shallow Christians if that’s why we’re in it,” she said. Lucifer, she points out, was the first worship leader, who in the traditional Christian understanding, was the most beautiful of all the angels, who led the heavenly choirs in praise of God. The first job, as Scarboro sees it, is worship of God for its own sake, a connection with the authentic.

Mittelstadt sees a parallel between the environment that launched the Azusa Street Revival, which came after a century of technological and industrial disruption, and the current preoccupation with things like artificial intelligence and the flattened experience of modern, technocratic life. He again invokes Taylor’s theory of enchantment. “The Enlightenment and modernity really moved us toward disenchantment,” he said. “Religions became disenchanted.” In the 21st century, he said. “There is this huge longing for re-enchantment.” He cites New Age movements, and even contemporary pop culture as evidence of this spiritual groundswell. Mittelstadt diagnoses what he says has traditionally been an allergy to postmodernity within Pentecostalism, and he finds it ironic: “We bring an enchanted world view to a world that is on a quest for enchantment,” he said. “We’ve never been merely rationally based.”