A Second Chance for a Jewish Education

As a child, I hated the classes at my synagogue’s cheder. Now I send my own children there—and I’m falling in love with Sunday school for the first time.

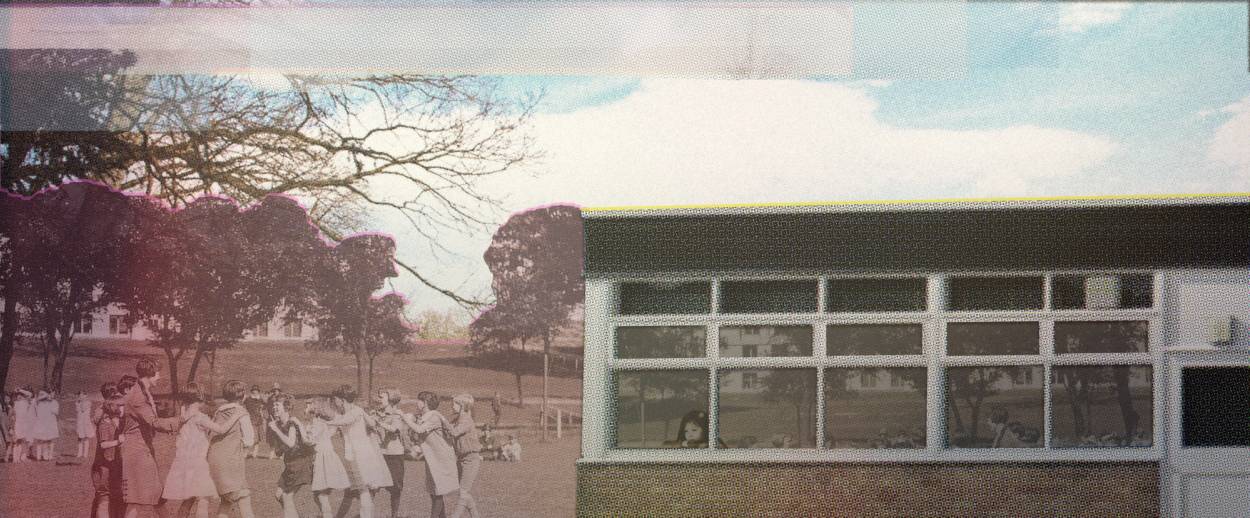

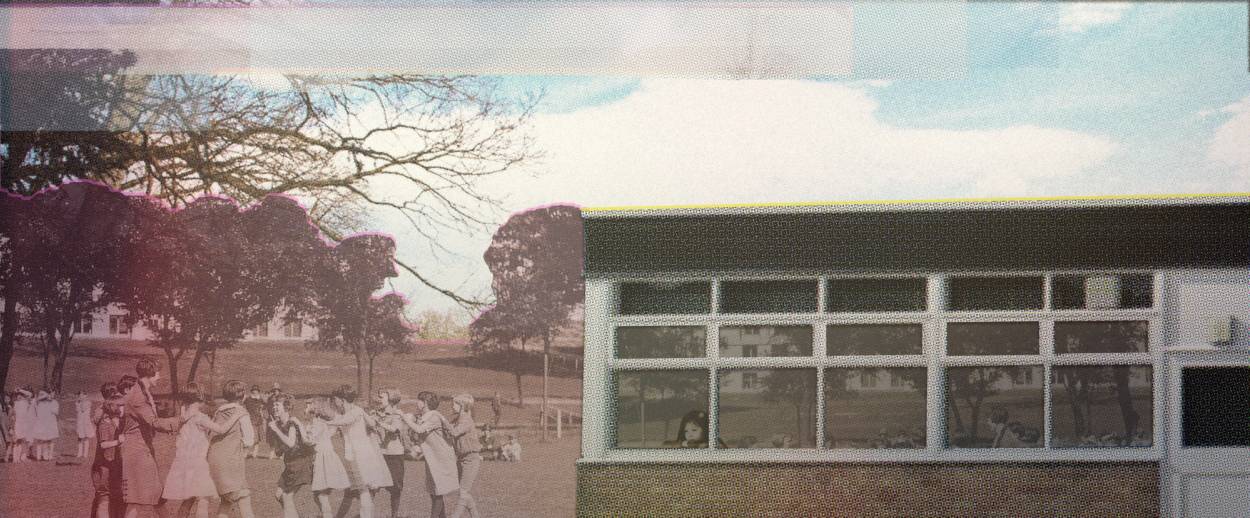

When I first walked my children into Sunday classes at the synagogue in Oxford, England, it felt like coming home after a long journey. The building had changed in the 22 years I’d been away, but the plastic curtains and utilitarian seats in the bleak, post-modern shul were still there.

I never thought I’d come back to Sunday school. Growing up, I hated cheder. Really, truly hated it. One of my clearest memories of childhood is of sitting in the classroom at the Oxford synagogue, aged 7, gazing at that plastic curtain, which separated my small group from the children a year above. “It’s 1986, and I am bored,” I imprinted on my mind, telling myself to remember this uninteresting moment for the rest of my life.

After I graduated from cheder at 13, my formal Jewish education came to a stop. I continued to work at the shul for a year helping at Sunday classes, and went to Habonim youth group meetings a few times, but from 15 onward, I was less interested in traditional Jewish studies and more in exploring “the meaning of life.” I continued celebrating Shabbat and festivals with my relations, but apart from that, I was relieved to be freed from what I saw as an unsoulful, anemic religious education, so I could study philosophy, poetry, and the Tao Te Ching instead.

By my twenties, although I celebrated Rosh Hashanah every year with my family, I was busy dating and establishing a career in London and still skeptical about organized religion. I felt a growing nostalgia, though, for that Jewish community I’d grown up with and found myself searching for my old cheder classmates on Facebook and joining JDate, thinking I’d actually like to have a liberal Jewish home. I still wasn’t sure I belonged at my hometown shul—or any shul—until I became pregnant with my first child and found myself literally knocking on my local synagogue’s door.

***

My father, whose first language was Yiddish, was the son of a small-town rabbi and shochet (ritual slaughterer) who had emigrated from Lithuania to South Africa. He met my mother in Cape Town at Habonim, where he was a madrich. My mother’s mother was deeply religious and a well-known Bible teacher. My parents had both grown up strongly culturally identified as Jewish. Once they got married, immigrated to England, and became members of the small, multi-denominational Jewish community in Oxford, it was my turn to follow in their Jewish footsteps.

My father is a kind man and was not strict as a parent, but when it came to Sunday classes, there was no arguing with him: I had to go. He and my mother were both brought up in observant, kosher homes, but they had been rebellious in their own way. My parents are atheists and see the Bible as a fascinating document rather than a rule book. In our household, although we did mark Shabbat and the major festivals and we didn’t have Christmas, we didn’t keep kosher and even bought the odd package of pork sausages. But what did matter, especially to my father, was that I should grow up properly educated about Jewish identity, culture, and history. He is extremely learned about Jewish history, and he wanted me to understand our roots.

I started “playshul”—the cheder’s pre-school—at age 3. That was fine; it just involved playing. And when I entered Oxford’s cheder proper at 5 and the actual Jewish education began, I willingly learned the first few letters of the Hebrew alphabet and several vowels. But a year or so down the line, I simply decided I didn’t want to learn Hebrew anymore.

I detested the little green “Lamdeni” workbooks we used with Alefs and Bets pictured jumping around in a playground. Looking back, I’m not sure why (the books look rather enticing to me today)—perhaps a teacher didn’t hold my attention, or perhaps I felt, in some way, resistant to being indoctrinated.

My defiance backfired on me: As the years went by, I became hopelessly lost, unable to follow what the others in my year-group of eight children were reading or writing. And so I became achingly bored every Sunday, in the way only a child can be. The vast majority of what we learned passed me by. I was barely listening in class and defined myself as the naughty girl, the lost cause. My teachers didn’t seem to like me and wrote reports criticizing my attitude and lack of attention. When it was time for Sunday classes, I did everything I could think of to get out of it, from begging my parents to let me stop to feigning illness to, more shamefully, lying, telling my parents it was a holiday when it wasn’t. Anything to miss a session.

The funny thing was that from Monday to Friday in mainstream school—a Church of England school, like most in England—I was academic and well-behaved. I remember wishing, at times, I could be Christian like everyone else—to get to have Christmas and sing “proper” hymns in English. It wasn’t that I didn’t want to be Jewish. It was that I ached for a religious education that was more powerful, more holy.

Cheder classes seemed dull to me and, strangely, not very Jewish. There was nothing emotional, nothing soulful—not like the intense stories my grandmother told me of biblical prophets and their inner struggles with God. She and my parents gave me what I saw as my real Jewish education: I loved my long, deep discussions with Gran about Jonah or Isaac; my Dad telling me terrible Yiddish jokes and laughing so much he couldn’t speak; our huge family Seders; the haunting melodies of Jewish folk songs. I also read about my people’s history, especially the Holocaust, from the diaries of Anne Frank and Hannah Szenes to When Hitler Stole Pink Rabbit.

Meanwhile our Jewish temple—a brutalist building plonked in a suburban row of semi-detached houses and lined with laminate flooring—seemed embarrassingly weak by comparison with my school friends’ soaring, beautiful churches. My friends’ Sunday schools taught them morals that seemed meaningful— “turn the other cheek”—and they had cool songs about Jesus, in English, sung with guitars. At cheder, which we called “Hebrew classes,” the acquisition of what seemed an impenetrable language was the focus, and this irritated me. Also, it was the 1980s; the Holocaust had happened only 40 years before. I couldn’t understand why the subject that frightened me so much and had affected all our families’ lives was never mentioned at cheder. Sunday classes felt irrelevant, divorced from living history and from the English world in which I lived.

Around the age of 12, when we finally started focusing in depth on Jewish history and the Hebrew lessons stopped, I started to enjoy studying under an inspiring elder, having a bat mitzvah, and attending occasional services with my dad. After graduating the next year, I stayed on every Sunday for another year, helping teach the children. But I still felt like a fraud. When a Jewish exchange student from France visited with me, she asked me why I wasn’t correcting the children’s mistakes when they read their Hebrew. I had to confess I had no idea what they were reading. I’d never got beyond being able to recognize the first half of the letters of the Hebrew alphabet.

I swore, all the way through my Hebrew classes, that I would never inflict the same on my children.

***

After all my JDating in my twenties, I ended up falling for Phil, a staunch atheist from a Catholic family in the far north of England. His interest in religion was less than nil, but he respected my Jewishness, and we agreed when I was pregnant with our first child that we would celebrate some Jewish customs and ultimately allow our son to decide what he believed in. As an adult, I had followed in my father’s footsteps—appreciating the culture and history of Judaism, while feeling no need to follow the laws of observance. I now wondered whether I would make my son go to cheder. What if he hated it, like me?

Then, when I was 29 weeks pregnant, we found out our baby was critically ill in the womb with a rare condition called hydrops fetalis, which was crushing his lungs. His life was hanging in the balance. When the doctors could do no more, I found myself praying, and then, one dark Sunday afternoon, driving to my local synagogue in Muswell Hill, north London. I’d never been before, and found it was another anonymous, brutalist building in another row of semi-detached houses. I could see the rabbi and a group of people having a small gathering inside. I knocked on the door until someone heard me and was ushered in, feeling surreal and biblical, with my swollen pregnant belly. I told my story to the amazed rabbi. I knew I’d never been here before, I said, and I wasn’t religious, but would he pray for my baby? He listened kindly and we lit a candle and prayed. When Humphrey was born, of course I felt close to the rabbi and the synagogue.

Humphrey spent his first five months in the hospital, where I found myself in the neonatal unit singing him, as lullabies, hymns we had sung every Sunday at cheder—Adon Olam and Ein Keloheinu. I didn’t know what the words meant—I never had—but the words and melodies were still in my head after all these years. I wanted my children to have these hymns in their heads, too. And I was hoping someone would teach them about the festivals and the prayers and the rituals—because I didn’t know enough to teach them.

As soon as Humphrey was well enough, I started taking him to the shul’s Shabbat playgroup, where we broke challah with the rabbi’s wife. I had a new yarmulke crocheted for my father to match Humphrey’s and together we started to celebrate Shabbat. Humphrey loved wearing his yarmulke and lighting the Sabbath candles from the start, and I knew then that I would send him to cheder one day.

Now that I was committed to this plan, I felt sad that I’d paid so little attention to my formal Jewish education and had barely taken in basic things I would now like to know—like what different festivals are about, why certain rituals are done, or what words in famous prayers mean. I now felt I’d missed out by not giving cheder a chance as a child.

After spending years in London, I moved back to Oxford with my family in 2014. One of the first things I found myself doing was looking up the Oxford synagogue website to find out if my children could go along to any activities. I enrolled my children—Humphrey Jonah is now 5, and my daughter, Lovell (or Liebe, after her Yiddish great-grandmother), 2—into playshul, the first rung on the cheder ladder. And I returned to the lessons I thought I’d never relive.

***

In many ways, Humphrey is like me—a natural-born rebel. At first, he didn’t like playshul. It was too busy, too noisy, too boring; he didn’t want to go. It does not even cross his mind to try to listen to the educational parts—when, after 90 minutes of free play and themed crafts, the leaders sit the children down and explain what festival or Bible story we’re celebrating this week or about one of the Ten Commandments, Humphrey simply ignores the lecture and talks to himself, usually about his current obsession: Father Christmas. Humphrey takes in absolutely nothing from playshul from a religious perspective—and yet continues to adore family Shabbats and asks searching questions about what happens when people die.

When playshul gets too much for him, I take him into the synagogue itself, and he instinctively calms down and feels at home there, with the Ark, tallitot, and prayer books.

Every time I walk down the corridor, I catch glimpses of faces I remember from my childhood—still recognizable years later—now back with their own children in tow. I’ve reconnected with teachers (it seems they didn’t think I was a lost cause after all) and quickly felt I’d found my roots back in a community that, to be honest, I wasn’t sure would welcome me after my childhood recalcitrance. My father sometimes comes along with us and gets a kick out of it as much as I do. Years ago, I spent all those Sundays singing Adon Olam not knowing what the words meant and watching the hands of the clock as they turned so slowly from 12:00 to 12:30 when I would at last be free to go home; now, in my thirties, Adon Olam moves me.

Talking to an old cheder contemporary recently, he said he had loved our years of classes here. But the thought occurred to us that perhaps questioning cheder (which I know I was not alone in) can be a valid, even normal, even formative part of being Jewish.

To be completely frank, at first on my return to cheder, I sometimes worried I didn’t truly belong. I still seemed to get in the way of authority every now and then. Once, when I took Humphrey into the shul for some calm, an older woman having an important meeting there voiced her disapproval. And I continue to find Hebrew a barrier. When we say prayers or sing together with the children, I am the only one, it seems, who doesn’t even try to mouth the Hebrew words; I just stand there looking awkward and embarrassed. But increasingly, I realize no one is judging me—and the building doesn’t bother me anymore; I now see it as a safe place, where I’ve always belonged, even if I didn’t understand that until now. I’m making friends and feeling, at long last, part of the community. I’m falling in love with Sunday school for the first time.

In September, Humphrey will move up into cheder proper—and I’m excited. There aren’t many Jews in Oxford, but through cheder, he will get to make Jewish friends his own age. The cheder leader is so full of fun ideas for the children that apparently these days they don’t want to miss a week. There are sleepovers, a summer camp, and all kinds of creative arts and drama. And when it comes to learning Hebrew, now that I’m grown up, I think, “How amazing to get to learn this back-to-front, ancient language.” I can only hope Humphrey sees it the same way, but I’m already looking forward to studying Hebrew along with him—and giving myself a second chance.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Olivia Gordon is a British freelance journalist who writes for a wide variety of newspapers, magazines, and websites.