Service With Spirit

Even as North Carolina’s Lumbees fight for official recognition, the Native American tribe maintains a distinct religious culture, blending Christianity with traditional rituals

Courtesy Kevin Melvin

Courtesy Kevin Melvin

Courtesy Kevin Melvin

Courtesy Kevin Melvin

Although they account for only 1.1% of a total force of over 1.3 million, Native Americans serve in the active-duty military at higher per capita rates than other, larger minority groups in the United States. An Army ceremony honoring National American Indian Heritage Month held at Fort Liberty, North Carolina, on Nov. 8 invited attendees to contemplate the complicated—but proud—legacy of military service among Native American communities. For many, service is not just a source of pride, but a way to keep spiritual traditions and rituals alive.

Fort Liberty is America’s largest Army base. Formerly known as Fort Bragg, it is home to the famed 82nd Airborne Division and various special forces units. It is also situated in an area of the state that has been inhabited by the Lumbees, a Native American tribe that lacks the federal recognition bestowed on household tribal names like the Osage, Cherokee, or Navajo. Native peoples lived by North Carolina’s Lumbee River for thousands of years (from which the tribe derived their name by a vote in 1953, having been called various things by the state since 1885). Today’s Lumbees, who number around 55,000 and live throughout several of the Tarheel State’s southeastern counties, are the descendants of those peoples. They are also an amalgamation of other tribes from the Carolinas and Virginia, refugees who came inland in response to disease, oppression, and war after the arrival of Europeans to the region beginning in the 17th century. A tribe shaped by the vicissitudes of European contact, the Lumbees’ own relationship to military service distills many of the past and present controversies that surround Native identity today.

One thing was made very clear at this year’s observance of National American Indian Heritage Month: There would be no traditional dancing, drumming, or dress, as there had been in years past. At Fort Liberty, this year’s observance, titled “Why We Serve,” would be focused squarely on the contribution of Native Americans in uniform. It was an intentional break from what Master Sergeant Garrick Stroud, who is both Navajo and Cherokee, referred to as a centuries-old tradition: When outsiders come into contact with Native Americans, he said, the typical demand is “dance for us.” Stroud, who helped plan the event, stood tall in his Army “pinks and greens” olive drab uniform and jump boots, covered with ribbons and medals indicating achievements in combat and training, and multiple deployment stripes on his sleeve reflecting four tours in Iraq. At this ceremony, held in the 82nd Airborne Division museum’s Hall of Heroes, he was adamant that the emphasis would be on the achievements of Native American veterans.

Kevin Locklear Melvin, tribal historic preservation officer for the Lumbees, served as the event’s guest speaker. The grandson of a WWII veteran, Melvin said that it wasn’t until after his grandfather’s death that his family learned, from talking to other veterans, that when the lifelong farmer told his family he was “going to check on the fields,” he was in fact attending veteran-only tribal ceremonies with other Lumbee veterans. Although the ceremonies can vary by tribe, Melvin said the two most common to southeastern tribes are known as sweat lodge and sunrise ceremonies. Melvin informed me that what goes on there is privileged information. Not even he himself knows, beyond anecdotal bits he’s picked up, since the ceremonies are closed to all but veterans. He said he knows Vietnam veterans who still attend such ceremonies on a monthly basis, as they continue to process their wartime experiences.

Courtesy Kevin Melvin

Like other tribes, the Lumbees have their share of veterans. Melvin gave a presentation on the tribe’s martial history that began with their engagement in the Carolinas’ Tuscarora War (in which the Tuscarora native people rose up against British colonists) from 1711-15, and later, the Revolutionary War. According to Melvin, the Lumbees’ loyalties were not exclusive. Some backed the British, some the Americans. Many fought for themselves, against any soldiers who impeded into Lumbee territory looking to avail themselves of their resources and livestock. Their loyalties were similarly fractured during the Civil War.

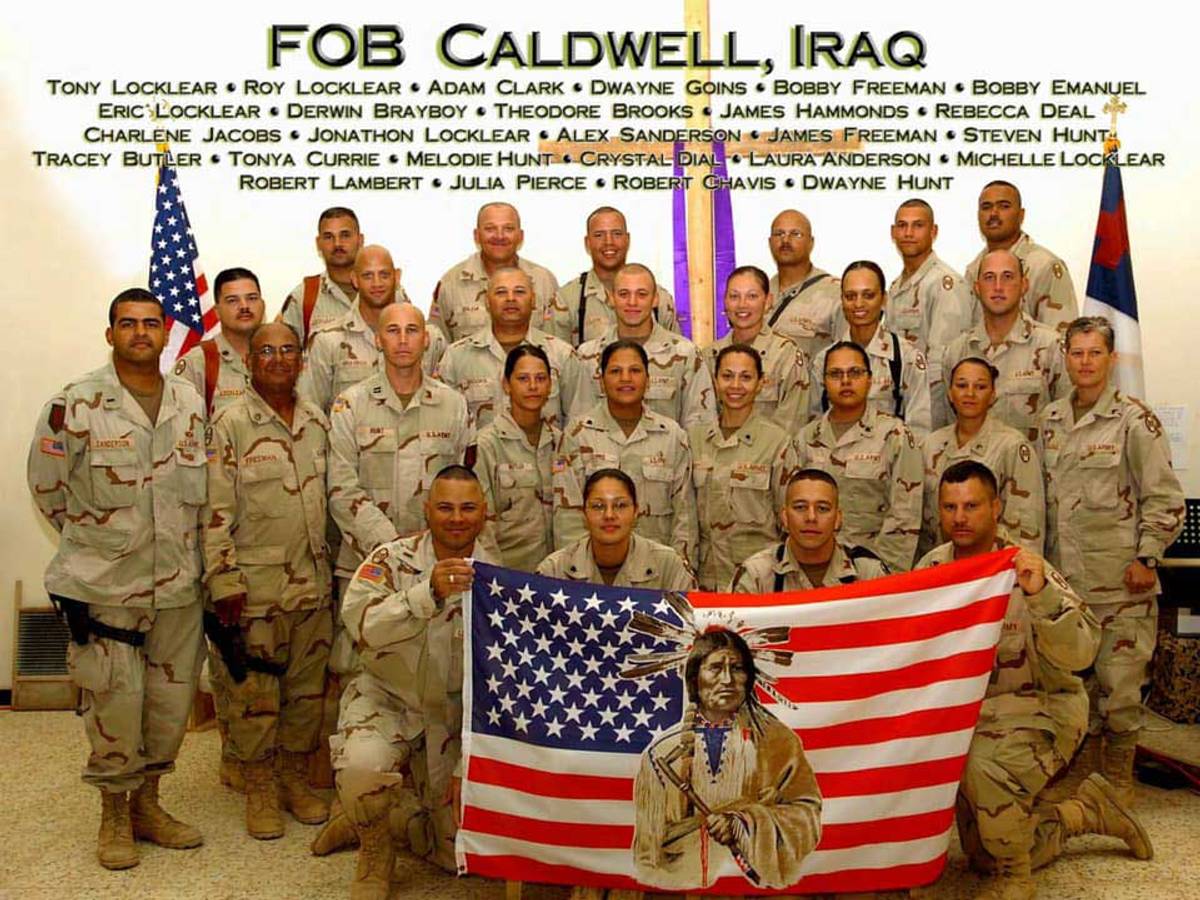

But by WWII, Lumbees were serving as Army doctors and Naval aviators (the first Native American to commission as a pilot in the Navy was Lumbee). Early in the second Iraq War, a group of Lumbee soldiers organized a powwow while they were deployed.

According to Stroud, the theme “Why We Serve” was chosen to address the paradox of Native Americans in uniform. Although not all the same, “each tribe has a lineage of being a warrior as a position within the tribe,” Stroud said in his remarks at the event. Indeed, much ink has been spilled on how pre-European contact understandings of what it meant to be a warrior informed later Native American military service in the U.S.

But Melvin’s presentation was focused on the reverse phenomenon: the way military service informs Lumbee community life. In his experiences talking with the Lumbee individuals he calls “pillars in our community,” Melvin said he finds that Lumbee veterans tend to attribute the life lessons and values that they learned in the military to their drive to become leaders back home as civilians: sitting on boards, running for office, or working in the medical and legal professions.

It is precisely this synchronicity of values that interests Stroud, who before he joined the military worked for the Cherokee Tribe, where he was impressed by the “responsibility of service” pressed upon him both by his father, and by Cherokee tribal leaders, something he said he didn’t initially realize was a value they shared with the military. Yes, the military provides certain economic and educational advantages to young Native Americans, but it is also, he said, a constructive channel for “the warrior spirit,” with its emphasis on selfless service.

Stroud, who is approaching the end of his military career after over two decades of service, said that he will take the Army values he has learned to build leaders in his civilian community.

Alongside the Pan-Indian Movement of the 1960s, which saw displaced tribes develop common intertribal identity markers as a form of solidarity, Native American veterans were key to the spreading of powwows across the United States.To honor their comrades from WWII and the Korean war, they revived and adapted rituals from various tribes.

One such example is the Gourd Dance, which began as a spiritual ritual for warriors that has been strongly associated with the Kiowa tribe since at least the 1830s (other Plains and Prairie tribes have their own versions), and is now a common feature at intertribal powwows. The Gourd Dance that the Kiowas revived in the 1950s is the descendant of a dance that gained prominence after the tribe’s preeminent cultural and spiritual ritual, known as the Sun Dance, was suppressed in the late 19th century, part of a U.S. government effort to stamp out native religion.

When members of the Kiowa sought to bring the Gourd Dance back after its popularity waned sometime in the 1920s, it caught on quickly. Other tribes soon developed their own Gourd Dance societies dedicated to propagating the ritual. Today, gourd dancing groups exist all over the country, but its warrior origins mean that it continues to have special spiritual resonance for veterans and often their families, for whom intertribal powwows will often set aside a dedicated portion of time. In a characteristic intertribal Gourd Dance, simple rhythmic bending and straightening of the knees is accompanied by a bobbing of the head, usually while shaking a rattle or other noisemaker. Military insignia, uniform items, and American flags may also be incorporated into the dancer’s outfit and accessories.

“The dance celebrates warriors’ victories and helps the healing process by providing fellowship and reminding veterans they are not alone, nor are they forgotten,” said a 2015 Kirtland Air Force Base article on a veterans’ Gourd Dance held at the installation’s hospital. “Now it’s like a healing ceremony for me,” one Marine Corps veteran was quoted. “When I go out there I dance for my family, for my brothers, sisters, sons, daughters, grandchildren, all the friends I’ve known, all the servicemen here and not here. Those I know who want to dance but they can’t. I dance for them, too.”

The Gourd Dance and its various iterations, as well as other ceremonies that can accompany both deployment and return from deployment, said Stroud, exist “to center us.”

Attendees at the Fort Liberty NAIHM event were shown clips from a 2019 PBS documentary, The Warrior Tradition. “People have asked me, with the history of the Comanche and the Kiowa, government taking your land, ‘Why did you go into the military?’” one veteran was shown saying. “Well, you know, we lost our land once. We’re not going to lose it a second time. It’s still our land.”

Over the years, what we ended up doing, was we took some of those traditional practices and kind of started intermingling it with Christianity and made it very unique.

Colonel Todd Borroughs, commanding officer of the 82nd Airborne Division’s Falcon Brigade, which sponsored the event, wrapped up the ceremony. The theme of Borroughs’ remarks was also identity. While the soldiers gathered that day were there to honor diversity, he said, above all, they were honoring soldiers and paratroopers. Thirty-three Medal of Honor recipients were Native American, he said. “Everyone,” Borroughs said, “brings something unique to the formation that makes the force stronger.”

As a tribe formed post-European contact, the Lumbees were Pan-Indian before the term existed. Their intermingling with other tribes, as well as with Europeans, means that it has been difficult for them to gain federal recognition as a tribe. Indeed, a theory about the tribe’s ethnic makeup posits that today’s Lumbees are actually the descendants of the “lost colony” of Roanoke. The initial European settlers to the area, around what is today Pembroke, North Carolina, found indigenous people with European features who already spoke English, and early 18th-century records indicate Lumbees who shared last names with Roanoke colonists.

According to Melvin, those names were common among English settlers in general, and the fair-complexioned, English-speaking Lumbee the settlers encountered were more likely the descendants of former European indentured servants, who had married indigenous women and moved inland to the Lumbee River area’s fertile swampland after they were freed.

Today, most Lumbees are Christian, predominantly Southern Baptists and Methodist, which Melvin also ascribes to intermarriage with European colonists, as well as to government suppression of indigenous religion. A 2018 Washington Post article, on one Lumbee woman’s struggle to claim federal benefits from the Bureau of Indian Affairs, describes church membership as “an essential part of Lumbee culture.”

Somewhat paradoxically, it is in these churches, Melvin said, that Lumbees have begun in recent years to rediscover lost traditions. In the past 30 years, the discovery of journals and letters from traders who came through the Lumbee River area have provided a window into the rituals and religious practices of the indigenous tribes of the region. These primary sources describe dances and ceremonies that chime with contemporary Lumbee culture, especially “in the way we church,” he said.

Brendan Smialowski/AFP via Getty Images

“You go to a Southern Baptist church anywhere in the country,” said Melvin, “and see the way Southern Baptist people worship. And then you go to a Baptist church in Lumbee country, [or other North Carolina tribes] the Coharie or the Waccamaw Siouan, and see the way they worship. And it’s very different.”

He gives the example of the stomp dance, a circular dance accompanied by call-and-response singing. In a Lumbee Southern Baptist church, he said, prior to the rediscovery of the European primary accounts of local native traditions, that type of call-and-response survived in a distinct preaching style that characterized Lumbee worship. There was also the dance itself. “When some of our church members feel the spirit of the Lord moving their body,” he said, “they get up, and they stomp around, kind of in a circle. That’s something that’s very unique to us.”

This phenomenon has occurred with other ethnic groups who have had their religion suppressed, for example, with the crypto-Jews in the American Southwest. These descendants of conversos during the Spanish Inquisition understood themselves to be Catholic, but unwittingly maintained vestigial Jewish practices, such as lighting candles on Friday nights, draining the blood of slaughtered livestock, and certain burial rites.

“Over the years, what we ended up doing, was we took some of those traditional practices and kind of started intermingling it with Christianity and made it very unique,” said Melvin. “So we really kind of hid it from ourselves.”

And as with other Native American tribes, it is culture, more than genetics, that matters to many Lumbees. The idea of a “blood quantum,” or the provability of Native ancestry, according to standards set by the federal government to determine eligibility for benefits, is controversial among many Native Americans, although it is still used by some tribes to establish citizenship. Some activists have taken to gatekeeping indigeneity, publicly calling out so-called “pretendians,” or white people claiming native status, which has in turn prompted its own backlash. One example of this kind of complicated cultural minefield is the recent controversy over native rights activist Buffy Sainte-Marie, who is alleged to have invented a Native American background for herself, as evidence surfaced that she was born to white parents. A family from Canada’s Piapot First Nation says that, having ritually adopted her as an adult, such recognition by their community “holds far more weight than any paper documentation or colonial recordkeeping ever could.” Sainte-Marie’s skeptics, however, maintain that such an adoption doesn’t confer true indigenous status.

MPI/Getty Images

When the Lumbees sought federal recognition after the passage of the Indian Reorganization Act in 1934, only 22 of the 209 Lumbees living in Robeson County, North Carolina, were found to meet the federal eligibility requirements of being over half Native American. And while Congress recognized the Lumbees as an American Indian tribe in 1956, this recognition did not confer federal benefits on them. Several decades later, the tribe continues to seek federal recognition. Other rationales for the holdup are given: Potential threats to Cherokee gaming rights elsewhere in the state are sometimes cited as an obstacle, as are the expansion of already limited healthcare benefits to thousands of newcomers.

In their quest to gain the benefits that come with federal recognition, the Lumbees struggle to be recognized even by other Native American tribes. In 2022, a group of tribes from around the country sent a letter to Congress opposing the extension of tribal benefits to the Lumbees. These tribes, which include the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians, and the Fort Sill Apache Tribe, maintain that by seeking congressional approval for their benefits, rather than going through the Bureau of Indian Affairs, as is more common, the Lumbees are opening the floodgates to “hundreds of other groups claiming to be tribes.” According to Melvin, however, because it was Congress who recognized the Lumbees with the Lumbee Act of 1956, it can only be amended by Congress.

In 2023, despite campaign promises of federal recognition from both 2020 presidential candidates, as well as legislation introduced earlier this year by North Carolina Sens. Thom Tillis and Ted Budd, the Lumbees of North Carolina continue to navigate a complex obstacles of genetics, history, and concepts of identity in pursuit of access to benefits from the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

“Oftentimes,” the 2022 joint tribal letter to Congress said, “groups seeking federal acknowledgment claim tribal identities that do not belong to them. Even more often, the people claiming to be descendants of known historic tribes cannot demonstrate tribal ancestry, or any Native ancestry at all.”

Melvin said that the Lumbees have historically faced two types of existential threat. One threat was domestic: outside groups trying to define the Lumbee identity, having their lands taken from them, or, in a notable case from the 1950s, fending off Ku Klux Klan members who were harassing Lumbees. In time, another threat arrived from abroad, in the form of foreign enemies to U.S. interests.

“We already know who we are,” Melvin said. Even though today’s Lumbees “have lost a lot,” he said, “we didn’t really lose everything.” Even as the Lumbee resurrect old rituals, those honoring warriors have been kept alive, because just like any other tribe—both at home and abroad—fighting has remained the one constant.

This story is part of a series Tablet is publishing to promote religious literacy across different religious communities, supported by a grant from the Arthur Vining Davis Foundations.

Maggie Phillips is a freelance writer and former Tablet Journalism Fellow.