Vienna Calling

I finally got citizenship from the country that persecuted my parents—just as things started feeling less secure in the country that offered them refuge

In late January—less than a week after the Colleyville synagogue standoff—I got a call from the Austrian Consulate in Los Angeles. My application for dual citizenship with Austria had been approved. What surprised me more than the personal phone outreach was my reaction to the news. After more than a year of deeply mixed feelings, I was elated.

Not that I’d worried about getting rejected. After September 2020, anyone with a “persecuted ancestor” from Austria was eligible to apply for restored citizenship. I knew I had a slam dunk case. Both my parents fled Vienna in 1939, forced to leave their families behind. Navigating a perilous new world on their own, Rita Rosenbaum and Paul Jarolim met in Brighton Beach, in an English language class for refugees. My mother liked to say that my father was attracted to her Viennese accent. She sounded like home to him.

It was a meet cute, only with Nazis.

Of their immediate family members, only one of my father’s brothers survived the war. All the rest—my maternal grandparents, my father’s sister and his other brother—had been deported and killed.

My parents rarely had anything nice to say about Austria, if they said anything at all. When my mother did refer to the country and its residents, it was generally with vituperative outbursts. She loathed the sudden celebrity in the 1970s of Arnold Schwarzenegger, the embodiment of muscular Austrian Aryanism. And she couldn’t stand the outpouring of praise for The Sound of Music. “With all that alpine schmaltz, you’d hardly know that the Nazis in the film were Austrians or that any Jews were being murdered,” she griped. My mother often swore that the Austrians were worse antisemites than the Germans, and claimed that Kurt Waldheim, the secretary general of the United Nations and, eventually, Austria’s president, was a Nazi.

Growing up, I didn’t really believe her. My mother was a nervous, cup-half-empty kind of person and, I thought, a bit paranoid. Everyone knew that the Austrians were victims, too, and that the Germans were responsible for …everything.

Happily, my mother lived long enough to see the world—and me—learn that Waldheim had voluntarily signed up for the Nazi party’s paramilitary wing and continued to take part in Hitler’s war efforts until 1945.

And she died before Schwarzenegger became governor of California.

But my mother kept a pressed edelweiss, that peculiar furry flower, among her belongings. And there was one detail of happier times in Vienna that she was fond of retelling: that one of her uncles had been Sigmund Freud’s butcher.

After a lifetime of aversion therapy against the country and its language—in spite of it being spoken in my home as a “secret” code, German sieves out of my brain when I try to learn it—I had no desire to visit Austria. Still, the Freud connection was intriguing. And when I discovered that my great uncle Siegmund Kornmehl’s butcher shop had been in 19 Berggasse, sharing that address with Freud for 44 years, I started digging into my family history.

It was a meet cute, only with Nazis.

It helps to have links to a famous person, if only by proximity, to access good archival records. A catalog for the “Freud’s Lost Neighbors” exhibition of Vienna’s Sigmund Freud Museum had a section devoted to Siegmund Kornmehl, detailing the exorbitant taxes levied on, and Aryanization of, his butcher shop, and Austria’s postwar obstruction of the return of their property at every juncture.

This was just the tip of the iceberg, I realized. My grandmother had six siblings in addition to her brother Siegmund and I knew next to nothing about most of them. There were other Austrian Jewish archives, other family landmarks, that I wanted to investigate firsthand.

In 2014, I donned my travel writer’s hat and headed for Vienna. I could use work as an excuse for the trip, and it would be tax deductible. I thought I had the perfect story hook: I would cover Vienna’s commemorations of the 75th anniversary of Freud’s death.

Astonishingly, I found a city that barely acknowledged its most famous Jewish resident. There was a larger-than-life statue in the heart of town of Karl Lueger, the antisemitic mayor whom Hitler cited as an inspiration for Mein Kampf, but not a single one of Freud. No major streets were named for the founder of psychoanalysis. Even Vienna’s kitsch was Freud-free: While Mozart tchotchkes, including a white-wigged rubber duck, were everywhere, I didn’t spot a single bearded sage with round glasses.

Eeriest of all, even his namesake museum was practically devoid of Freud. Except for the bookshop and the waiting room for which Anna Freud sent back a few of the original furnishings from London, where the family was forced to flee in 1938, the rooms of the Sigmund Freud Museum were largely empty. The museum’s planned commemoration of the 75th anniversary of Freud’s death—the only one I found in Vienna—was similarly minimalist: A “Hidden Freud” exhibition would post 16 pictures in biographically significant public places throughout the city, but the text accompanying them would only be in German and only accessible via a QR code reader. Any foreign visitor without translation or QR scanning apps—or, heaven forfend, without a smartphone—would be out of luck.

A city that could erase—or as Freud’s biographer, Peter Gay, put it, repress—such an internationally renowned Jew clearly had not come to terms with its Nazi past.

Still, I continued my personal-history-oriented visits to Vienna. And I started noticing changes in Austria’s attitude toward Freud and, more significantly, to its less renowned Jewish ex-residents. On June 4, 2018, exactly 80 years after Freud and his family left Vienna, the first full-size statue of Sigmund Freud, by Jewish sculptor Oskar Nemon, was dedicated outside the Medical University of Vienna. The Freud Museum underwent a major renovation that made its namesake more of a living presence. I began to see a proliferation of Freud dolls, keychains, and even a miniature plush couch alongside Mozart memorabilia.

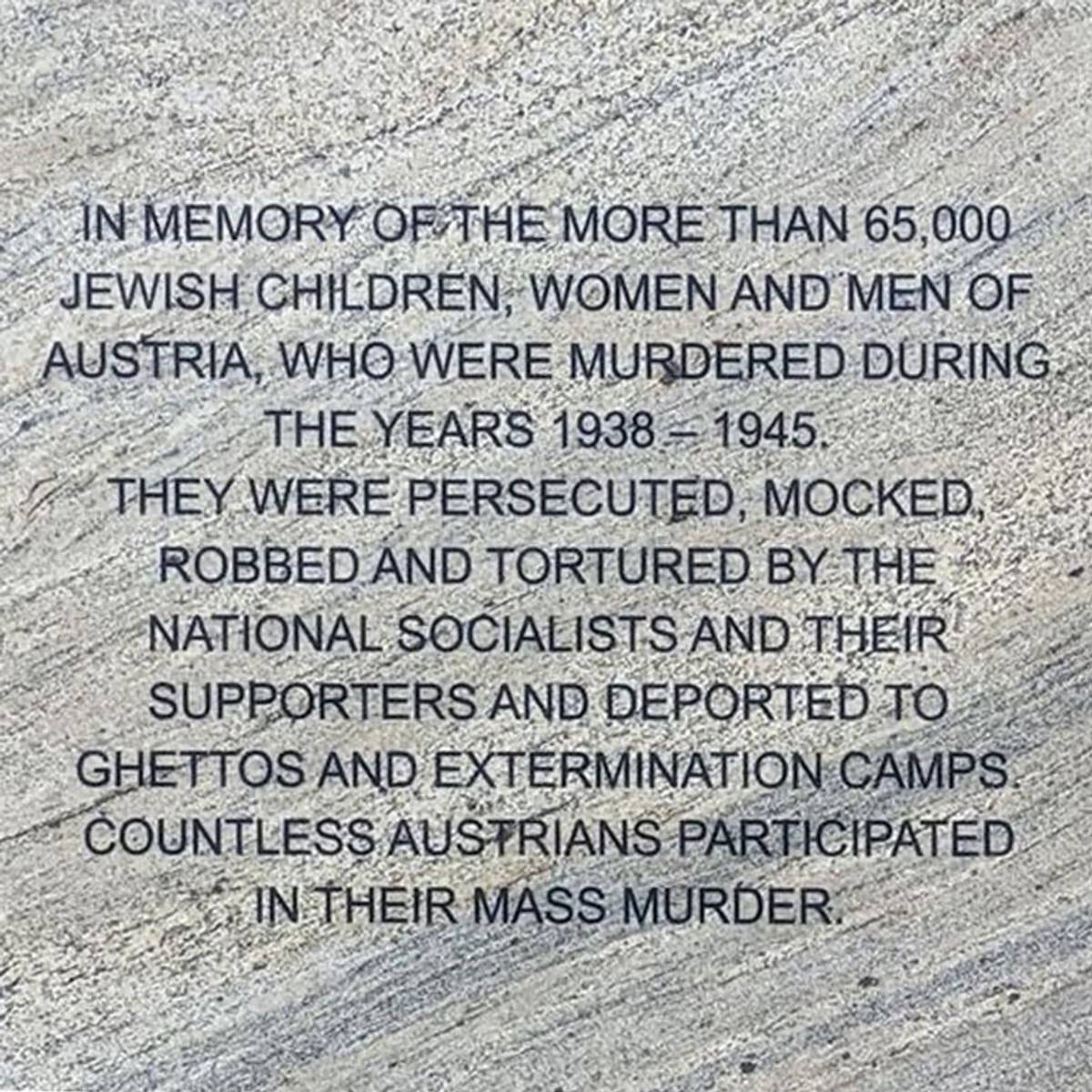

Those larger changes? Along with Austria’s offer of citizenship to ancestors of persecuted individuals in 2020, the Shoah Wall of Names Memorial was dedicated in Vienna on Nov. 9, 2021, the 83rd anniversary of the Kristallnacht pogrom. Similar to the Vietnam Memorial in Washington, D.C., in its simplicity, it is very explicit about Austria’s complicity.

When the possibility of Austrian citizenship arose, I thought long and hard about applying. I had no practical reason to seek a legal connection to the country. I don’t have children, I don’t need an EU passport—though I like the idea of getting through immigration lines more quickly—and, in spite of my roots and pleasant recent visits, I never warmed up to Vienna. I prefer more vibrant, grittier cities like Paris or my hometown, New York. And ones that didn’t send my relatives off to be murdered.

But if revenge is a dish best served cold, I was ready to dine. Wasn’t the restoration of what was stolen from my parents, a declaration that they couldn’t get rid of us so easily, reason enough to apply?

Apparently not, said my subconscious (thanks, Freud).

I filled out the preliminary application in October 2020 and waited so long to follow up that I forgot I had already emailed it to the Austrian Consulate several months earlier. So long that I let my hair go pandemic gray and then started obsessing about putting gray-tressed images on my new Austrian passport (which I was nowhere close to getting). So long that I read at least four more books about the Holocaust in Austria that confirmed my mother’s claims about the country’s antisemitism.

And when I finally did start working on the forms, I subverted their progress. This was around the time of the 2020 election, and Postmaster General Louis DeJoy had started messing with the mail. Expensive sorting machines were being taken offline, mailboxes were being physically removed … and yet I dropped my original birth certificate, required for proof of identity and relationship to my persecuted ancestor, into a mailbox that looked weather-beaten and abandoned, possibly unattended by a human postal person for years.

But slowly, slowly, I gathered all the necessary documentation. I learned terms like “apostille,” a form of document verification. And, after having my fingerprints run through a U.S. government database, I confirmed that I was not wanted by the FBI.

In October 2021, I submitted the completed application.

At around the same time that I started visiting Vienna, I became aware of the increase of antisemitism in the U.S. In addition to the right-wing kind I’d been most familiar with—the scrawled graffiti swastikas, the demonization of George Soros, and the Tree of Life synagogue shooting in 2018—I started noticing antisemitism among progressives, my political cohort. On college campuses, in leftist groups, and in the nonpolitical professional organizations I belonged to, everything to do with American Jews seemed to be filtered through the lens of Israel and Zionism. Suddenly, I was no longer part of a persecuted minority, but a white colonialist. Every statement in support of diaspora Jews had to be caveated by an addendum to the effect of “this doesn’t mean we don’t support Palestinians, too.”

Gaslighting, especially instead of expected allyship, felt more threatening than overt Jew-hatred. It meant I couldn’t discuss my fears with progressive non-Jewish friends, or even with several Jewish ones, lest I appear overwrought, paranoid—all the traits I attributed to my mother for so many years. Karma is a bitch, isn’t it?

The hostage standoff in the Colleyville synagogue was a tipping point for me. I was shocked at how an obvious hate crime against Jews was underplayed or explained away. By the FBI. By the press that didn’t emphasize that the rabbi saved the day, or that Jewish clergy now need to be trained for precisely these situations. By the “nobody died,” “it could have been a church,” “we hate all gun violence” crowd.

And this is why, I realized, the call from the Austrian Consulate a week later felt so satisfying. It wasn’t revenge I craved after all, but clarity. I’d needed simple, direct acknowledgement of being wronged and the offer of a remedy, however toothless and belated.

It’s distressing to feel more seen by the country that persecuted my family than I do by the one where they found sanctuary. I can only hope that it’s not too late for the tide to turn, and that future generations of American Jews won’t have to be grateful for restored citizenship and a memorial wall.

Edie Jarolim writes about food and travel for a variety of national publications, and blogs about genealogy, psychology, and meat on FreudsButcher.com.