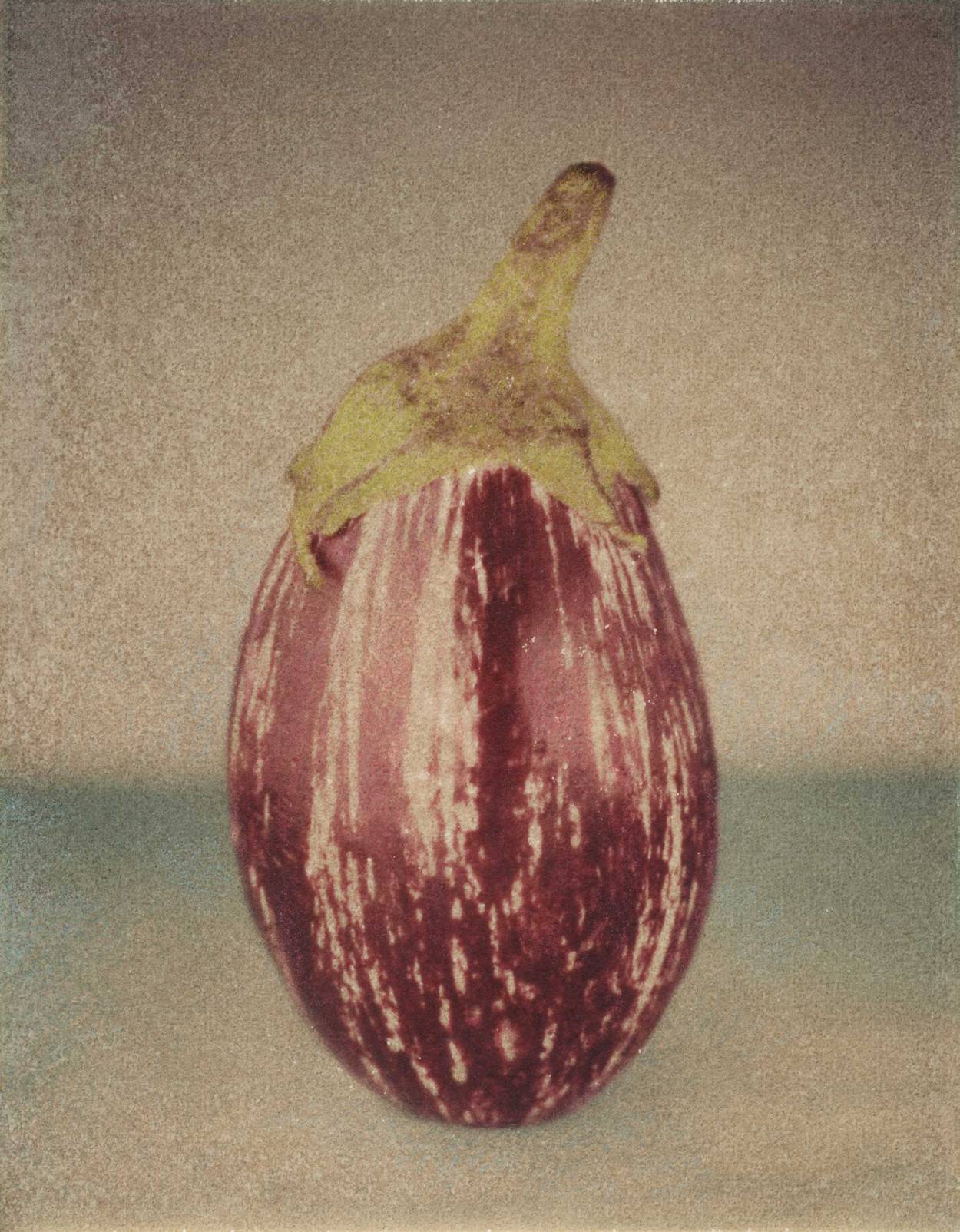

From Stigma to Staple

The eggplant is a symbol of Sephardic resilience, identity, and survival

Jennifer Kennard/Corbis via Getty Images

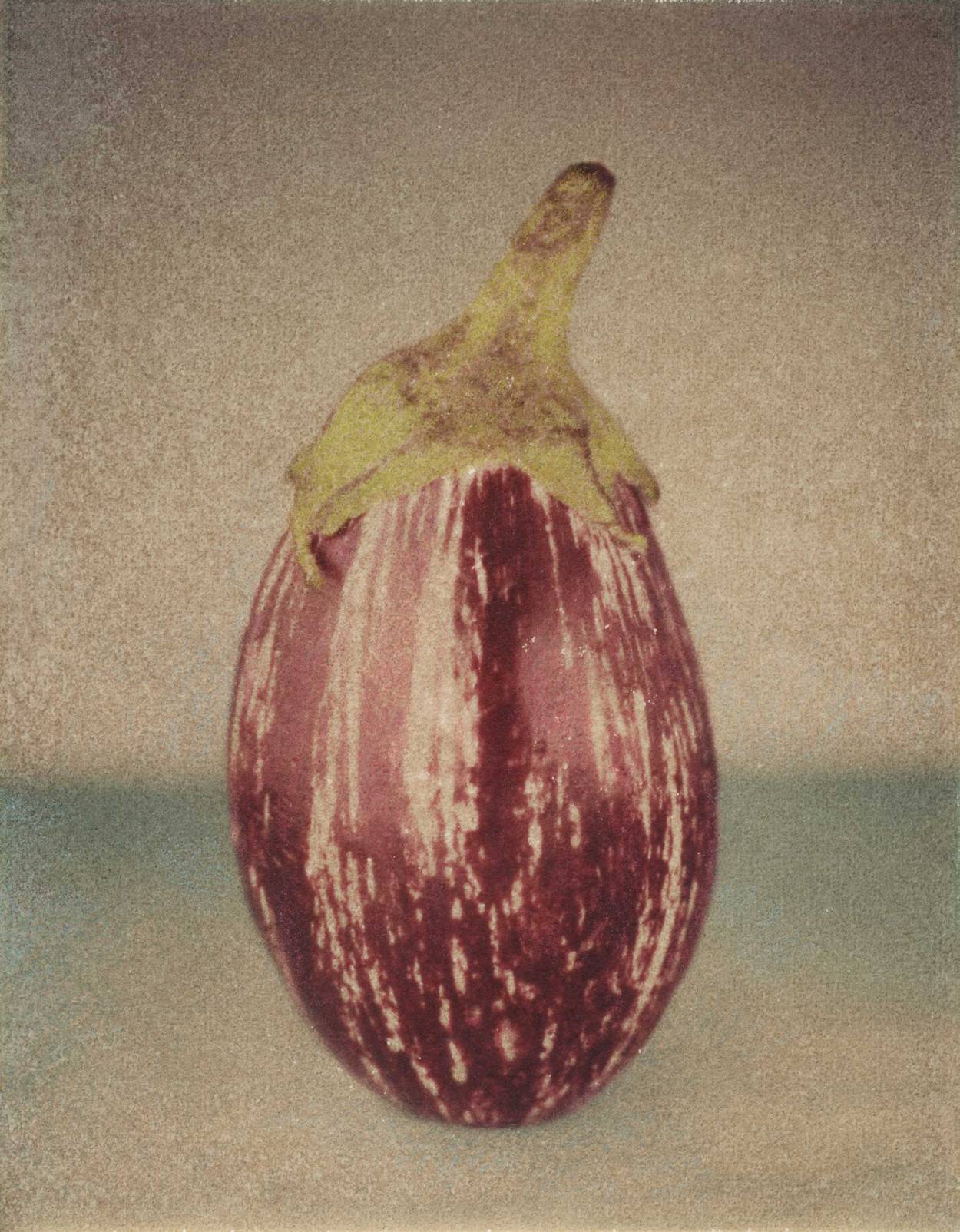

Jennifer Kennard/Corbis via Getty Images

Jennifer Kennard/Corbis via Getty Images

Jennifer Kennard/Corbis via Getty Images

On a recent jaunt to the heart of Spain’s Segovia, it wasn’t the grandeur of the Roman aqueduct or the history-soaked walls of the synagogue-turned-Corpus Christi Church that buzzed me. No, it was the anticipation of a meal at El Fogón Sefardí (The Sephardic Cookpot), a quaint bistro tucked away in the Jewish quarter. Esteemed as one of the rare spots in Spain to dish out genuine Sephardic medieval delights, it promised a culinary time machine back to the era of Spanish Jewry. For eons, my taste buds had fancied the treats on their menu. But, to my chagrin, a swath of Sephardic dishes were struck off. Mariano, the ever-accommodating maître d’, lamented as I yearned for the berenjenas caramelizadas con miel (caramelized eggplant with honey), “Sorry, we took it off the menu; those dishes rarely get any takers.” Quick on his feet, he chipped in with an alternative: “But might I tempt you with a succulent suckling pig paired with caramelized apples?” A twist, indeed.

The reluctance toward dishes like the sweet-and-sour eggplants cooked in olive oil and honey and spiced with cinnamon speaks to Spain’s complex culinary history. Specifically, it hints at the controversial status of the eggplant in the country’s past. Despite its abundant presence in various regional cuisines, the humble eggplant, now a celebrated culinary staple, once suffered intense scrutiny and stigmatization in medieval Spain due to its Semitic origins.

“In the Middle Ages, eggplants were considered poisonous,” said Ana M. Gómez-Bravo, Spanish and food studies professor at the University of Washington. “Being a vegetable associated with evil, anyone who ate it who didn’t die was also evil.”

Tracing the history of eggplant in the Iberian Peninsula leads us back to the eighth century when the Moors introduced it. Solanum melongena is one of the few edible solanaceous plants that do not originate in America. Originating from India, the eggplant was widespread in ancient Asia and the Middle East, even mentioned in the significant Chinese agricultural treatise Qimin Yaoshu (fifth century CE). However, the old crop didn’t leave significant footprints in Greek or Roman literature, despite these civilizations being familiar with other poisonous nightshades, such as henbane, belladonna, stramonium, and, above all, mandrake, whose fruits are similar to small eggplants.

The esteemed 10th-century Kitāb al-tabīj, The Anonymous Andalusian Cookbook written by Ibn Sayyar al-Warraq, offers a window into the culinary and religious traditions of medieval Muslims and Jews. Of 543 recipes, 62 showcase the eggplant in various preparations, including one recipe called Eggplant, Jewish Style. The book is in the National Library of France and listed as Arabe 7009, Recettes de cuisine.

Other medieval European references include mentions from Abū ‘l-Khayr in the 10th-century Calendar of Cordoba and the 11th-century Agronomic Treatises, known as the Kitāb al-filāḥa in Arabic. Thirteenth-century Sevillian botanist Ibn al-’Awwām detailed the cultivation of eggplant in al-Andalus, identifying four varieties—white, reddish-purple, black, or brown—and even likened its appearance to “an egg in the skin of a hedgehog.” Known as Abu Zacaria of Seville, Ibn al-’Awwam highlights eggplant’s cultivation in the ancient Roman city of Aquileia (near modern-day Trieste, Italy) despite little evidence of Roman authors discussing the vegetable.

As the centuries progressed, the acceptance of vegetables in Europe wasn’t universally positive, as it had been during the golden age of Jewish culture in Spain. Historical cookbooks such as the Novellino and the Tacuinum Sanitatis from the 13th and 14th centuries helped spread prejudice against the eggplant by describing it as pomo sdegnoso (disdainful apple). By the 16th century, it was prohibited as a food in England and neglected in Germany, though still cultivated ornamentally. In the Italian Renaissance, humanist Ermolaus Barbarus dubbed the eggplant malum insanum (mad apple), a term that shaped the vegetable’s current name in Italian, melanzana, far from what the Arabs called it: al-badinjan, which produced both the French aubergine and the Spanish berenjena. The ill-natured names reflected the disdain eggplant faced at the time, an attitude evident in Antonio Frugoli’s 1631 treatise where the gastronome suggested “delicate fruits to serve at any table of princes and great lords” while the rest of vegetables like eggplants were only “fit for peasants or Jews.” This derogatory perspective against Jews persisted into the 17th century, with agronomist Vicenzo Tanara reiterating the vegetable’s association with lower societal classes.

This negative reputation wasn’t limited to cultural discourse. Many in the medical field, influenced by the theory of humors, believed eggplants to cause various ailments.

“It was believed that its consumption caused phlegm, one of the four elements of humorism, which is why it was frowned upon by the Christian authorities and monarchs of the time,” said Gómez-Bravo, “because it was believed that humors determined the character of a person or people. In this case, this entrenched medical discourse of the time stereotyped the Jewish body and culinary customs as inferior and impure.”

Avicenna, a respected 10th-century physician, blamed the vegetable for illnesses ranging from leprosy to epilepsy. “Whoever eats eggplant engenders melancholy and weakness in the liver and spleen,” he wrote. As Diego de Covarrubias, a Roman Catholic prelate, stated, eggplants were believed to have adverse effects on one’s disposition and health. Even Sephardic Jewish philosopher Maimonides, in his famous The Regimen of Health, disregarded eggplant along with garlic, onion, leek, radish, and cabbage: “These vegetables are terrible for whoever wishes to follow a healthy diet alone.”

Its near absence from cookbooks under Christian dominion hints at a larger ambition to eradicate the culinary traditions associated with the Jews and Moors. Fortunately, this endeavor was unsuccessful, as several manuscripts documented these communities’ rich and diverse culinary traditions. Notably, medieval and early modern Castilian and Catalan cookbooks, such as the Libro de guisados by Ruperto de Ñola (1520), spotlight the eggplant as a dominant ingredient. For example, in dishes like cazuela mojí, eggplant slices are fried and combined with roasted bread, spices, and cheese, followed by a mix of beaten eggs, pepper, saffron, and clove.

The popularity of eggplants among the Sephardim transcended beyond the sculleries’ confines, as evidenced in literature, music, poetry, and popular culture. For instance, in Francisco Delicado’s Portrait of Lozana (1528), the protagonist, Aldonza, boasts of her cooking talents while revealing her Jewish provenance: “Do I know how to make boronia? Wonderfully! And eggplant cazuela? To perfection!” Converso ancestry was often denoted by what they ate; food usually gave people’s tradition away, ultimately leading to their persecution and killings solely for professing to observe Judaic dietary habits.

As reflected in David Gitlitz and Linda Kay Davidson’s book A Drizzle of Honey: The Life and Recipes of Spain’s Secret Jews: “Late fifteenth-century conversos were evidently so fond of eggplant that the satirical literature of the day is filled with pointed references to this predilection.” Typical is the burlesque poem by Rodrigo Cota about a converso wedding at which the guests were served this vegetable. The tribunal of the Inquisition of Toledo even accused several families of Judaizing for the preparation of these dishes after they were denounced by neighbors, friends, and even servants. “What’s remarkable is how closely some of these recipes are to what we find in the Inquisition testimonies,” said writer, chef, and cooking instructor Susan Barocas.

Baltasar de Álcazar, another converso writer, celebrates bravely with irony in a poem about the virtues of eggplants, where he slips in ham so people won’t suspect his Jewishness; unfortunately, his passion for the known Jewish vegetable gives him away.

Tres cosas me tienen preso

De amores el corazón:

La bella Inés, el jamón

Y berengenas con queso.

My heart is a prisoner

In love with three things:

Beautiful Inés, ham

and cheese with eggplants.

Berengeneros (eggplant eaters) was even a pejorative term used to insult someone suspected of having Jewish heritage or showing their Jewishness publicly. The so-called old Christians considered the vegetable undignified food eaten by crypto-Jews. In cities like Toledo, considered the heartland of medieval Iberian Semitic culture, the term was used with contempt by the inhabitants of the nearby towns of León or Valladolid to refer to those who were thought not to be of pure blood—that is, to have Jewish or Moorish roots.

Oral tradition played a crucial role in the collective memory of Sephardic Jews in Spain and the diaspora. The preference for certain foods toward specific edibles also made its way onto the collective bodies of folk narrative ballad poems called Romanceros and Cancioneros. These orally transmitted works were a powerful tool used by Jewish women to teach their daughters the komidikas (recipes) of their families, the traditions of the holidays, and Hebraic rituals.

“The communal and musical aspect of these gatherings played a crucial role in passing these recipes from women to women as they cooked and sang together,” said Barocas.

The collection of ballads that constitute the corpus of texts where eggplants are found consists of almost 2,000 versions. The verses that come to us from the Sephardic people of the Ottoman Empire and North Africa have reached great popularity since the 18th century. The burlesque lyrics turned into rhymes and songs, helping the memorization of the recipes, which Sephardim carried and maintained orally throughout the lands that sheltered them after the Spanish expulsion—mostly the Ottoman Empire and countries in northern Africa such as Morocco and Algeria.

Among the most popular kantikas (poetic chants) that speak of eggplants and the way to cook them are those collected on the island of Rhodes, like Siete Modos de Guisar las Berenjena and Los Gizado de las Merenjenas. The latter contains 36 ways to stew the vegetable. Over time, the myriad eggplant dishes of the Sephardic Jews have influenced and enriched the Mediterranean, Maghreb, and Middle Eastern cuisines. Today, popular dishes like Greek moussaka, Italian vegetable frittatas, Catalan escalivada, pickled eggplants from Almagro, traditional cold purees from Greece, and Andalusian fried eggplants all bear the indelible mark of this culinary heritage.

The enduring legacy of the eggplant in Sephardic culture is a testament to more than just culinary tastes; it’s a poignant chronicle of identity, survival, and evolution. As modern palates worldwide savor its rich flavors and textures, they are simultaneously tapping into a rich tapestry of history. From the ancient streets of Toledo to contemporary kitchens around the globe, the eggplant is not just a dish’s main ingredient but a bridge connecting generations, reminding us of the profound ways in which food transcends borders and time, weaving together stories of celebration, endurance, and deep-rooted heritage. Today, as chefs and home cooks alike revel in the versatility of the eggplant, it stands as a vivid emblem of its storied past, symbolizing the journey of the Jewish community, our unwavering resilience, and an unyielding commitment to preserving our identity, no matter the challenges faced.

“It’s all about continuity. Whatever the circumstances we have faced—the Inquisition, the expulsion from Spain, the Holocaust, and the wars—we’ve always persevered, adapting and growing with every new experience,” said Barocas. “We created new lives there to the places we went, and these places, these cultures that embraced us contributed and added to our culture, cuisine, music, language, even to our prayers. We used it, and we survived. And we’re gonna keep doing it.”

Orge Castellano is a Madrid-based journalist, writer, and social scientist.