The Flavors of Netivot

Once an absorption center for North African immigrants, this city in southern Israel has developed a culinary scene that draws on its past, but with the occasional new twist

A one-hour drive to the south from Tel Aviv brings you to another world. The southern Israeli city of Netivot is not generally considered a tourist attraction (except for the tomb of the Baba Sali, the city’s leading Moroccan rabbi and miracle worker who died in 1984 and whose grave has become a pilgrimage site for his followers). But enthusiastic recommendations on Facebook of a culinary tour held in the city sparked my curiosity, and prompted a visit: I wanted to find out more about the food of Netivot.

Originally known as Azata, Netivot was established in 1956 as a ma’abara—an immigrant absorption camp providing temporary housing—populated by olim from Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia. Soon after, the name was changed to Netivot and it grew into a “development town,” which was the name for new permanent settlements that popped up in the Negev in the south, as well as in the Galilee in the north, as a means to spread the population all over Israel, so it’s not all in the center of the country or around Jerusalem.

Like its original settlers, Netivot’s culinary profile is North African. The city’s history makes it a great place to eat an authentic Tunisian brika (a deep fried, wafer-thin pastry filled with a raw egg) or a Tunisian fricassé sandwich (a fried bun filled with potato, harissa, tuna, black olives, and a hard-boiled egg), or perhaps to buy Moroccan spices. But Netivot isn’t a little development town anymore, and its culinary palate grew beyond the traditional recipes that its early settlers brought with them to Israel. In the 1990s many immigrants from Russia and Ethiopia came to Netivot and in the year 2000 it was officially declared a city. Today it is considered a metropolitan area for the northern Negev, and it is rapidly growing with the help of government funding. Nowadays Netivot’s population counts more than 42,000, while 10,000 of those moved to the city in the past 10 years alone.

Our tour guide—35-year-old local entrepreneur and social activist Einav Levi—was born in Netivot to a Moroccan family. After a few years living elsewhere, she returned to Netivot. She comes from a background in film and owns a company specializing in visual media and independent films. To that she added an initiative called “I Love Netivot“ in which she hosts culinary tours.

“I love my city and I feel there is a huge gap between how I view Netivot and how it is perceived in the rest of the country or how it is portrayed in the media,” she told me. “People talk about Netivot as a peripheral place, of low socio-economic status with a mostly Haredi population, and it isn’t like that anymore—if it ever was. I feel people view Netivot very stereotypically and I felt that through culinary tours, I can invite people in and let them make up their own minds.”

One of the things Levi shows in her tour is that even the traditional Jewish North African cuisine that the people of Netivot grew up eating has developed and changed over time. Take, for example, popular food stand Yawaradi (a slang word meaning “wow!”), which operates every Friday in the lot where Netivot’s old market used to stand. The market moved to a new location about 20 years ago, but Yawaradi, as well as a few sporadic and changing stands, still operate in the old lot on Fridays. Yawaradi, which is packed and full of atmosphere with Mizrahi music blasting from the speakers, specializes in Moroccan-style fish in spicy red sauce served in frena bread, which is baked fresh right in front of your eyes in a portable tabun oven. But it’s no ordinary Moroccan fish and no ordinary frena bread, either.

Frena is Moroccan flat bread, reminiscent of a very fluffy pita. Usually, the frena dough is left to rise for between three and five hours, depending on the weather. But at Yawaradi they leave it to rise for 72 hours, like Neapolitan pizza dough. Inside your frena bread you can choose one out of three options—tuna fish, fish roe, or fish patties—all cooked in a Moroccan style with a twist. For instance, Yawaradi’s red sauce includes Greek Kalamata olives, and the side dishes that you can add to your frena fish sandwich are more Mediterranean than Moroccan: garlic confit and antipasti, for instance.

“Netivot is a city pf people who know good food,” Levi told me. “Everyone grew up with ethnic home cooking. Everyone’s mother and grandmother cooked. Nowadays Netivot’s food scene has many influences from the outside. People are open and curious to new tastes, as long as its kosher.”

The majority of Netivot’s population is observant, with a large Sephardic Haredi population. And all of the restaurants, food stands, or eateries in Netivot are kosher. (Not all of them are certified, but all of them are kosher.) What people do in their own homes is their business, however, and even though most of Netivot’s population is religious, they welcomed Russian and Asian supermarkets into their city—the latter opened to cater to migrant workers—even though they carry nonkosher products.

David Peretz, a journalist and musician who grew up in the south of Israel and still resides in Be’er Sheva, is a big fan of local, home-cooked cuisine. “For years I found it funny that people came to look for restaurants in Netivot,” he told me. “The best food you could find in Netivot was to knock on any door and say you’re hungry. The best food was cooked at home by the mothers and grandmothers who came as immigrants from North Africa. They brought with them recipes that were perfected and honed through the generations. The Jewish cooking in North Africa was very different to the cooking of their Arab neighbors. It was its own language. It wandered between Jewish communities throughout North Africa and in each place developed a different accent. The olim from North Africa were sent to development towns, so places like Netivot, Yeruham, Sderot, and Ofakim kept North African cooking traditions alive.”

For years, in Netivot, this cooking remained in the homes. There was no one to sell it to because everybody had this food at home. “Generations had to pass for it to be rediscovered,” Peretz explained. “Many women of my generation abhorred the idea of staying in the kitchen like their mothers and grandmothers did. Luckily the young generation, the grandchildren, understood what they have in their hands and the fact that they can use this knowledge to make magic, as well as money. Since Netivot is a very traditional city, it retained this knowledge. Nowadays there are many stands selling this food in Netivot and it’s suddenly becoming fashionable. And rightly so. It has exaggerated tastes, it’s in your face, and it is filling and fulfilling. There are many great food stands in Netivot but they’re still not as good as what you’d find at the Shabbat table or at a wedding table.”

One of the things you would find at any of these tables is the aforementioned Moroccan frena bread, which is the most widely consumed type of bread in Netivot.

Netivot Bakery is an old-school style bakery that provides baked goods to a large part of the city’s population as well as to many of its eateries and catering businesses. It, too, had to develop from how things were traditionally done. Traditionally, frena was baked in a small mud oven, in which they were baked one by one (or two by two, tops). This was done manually: You put the frena in the oven and pull it right out. In a commercial bakery this obviously isn’t possible because you have to make thousands of frena breads a week. So, at Netivot Bakery they tweaked the recipe to be able to keep the original flavor and consistency while using an industrial-size oven and baking on a large scale.

Everybody eats frena in Netivot, and some find new uses for it. At La Frena restaurant, for instance, they serve hamburgers, schnitzels, and kebabs in frena bread. La Frena is located in the new Manhattan-Netivot neighborhood, which includes 15 new buildings and a replica of the Statue of Liberty, holding an apple with the number 15 instead of a tablet in her left hand. Local real estate magnate Oded Shriki, who had recently been in the news in a less favorable context (he was questioned in regard to tax evasion), is the man behind this as well as another international monument that has made its way to the south of Israel: Netivot’s very own replica of the Eiffel Tower. This Instagrammable structure stands proudly in the middle of Shriki’s Paris Center, a stylish open mall with Parisian chic.

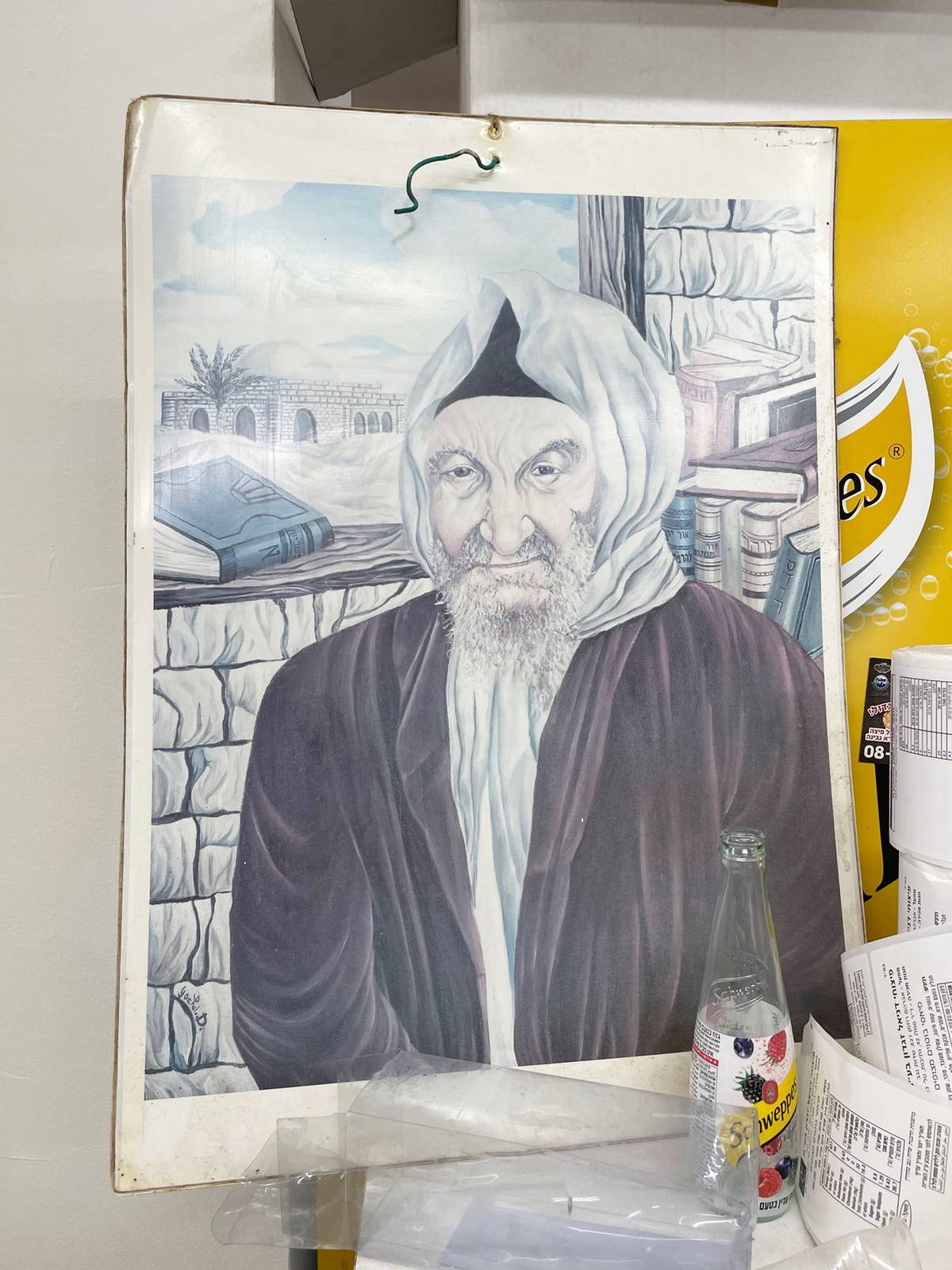

These two Vegas-like monuments in Netivot are secondary in landmark status only to the tomb of the Baba Sali. And indeed, any bakery, falafel joint, and grocery store I entered during my visit to the city had at least one portrait of the Baba Sali hanging on the wall.

But the Baba Sali is the past; hamburgers in frena bread are the future.

Dana Kessler has written for Maariv, Haaretz, Yediot Aharonot, and other Israeli publications. She is based in Tel Aviv.