A Mystery Baked Inside a Cake

My explosive mission to recreate the ‘pain d’espagne’ my grandfather once made, which I never got to eat

Late one afternoon, during the first dark days of the fall when I was 5 or 6 years old, my grandfather turned to me and said a thing I never expected to hear: “Why don’t we bake a pain d’espagne?”

With both parents and my grandmother at work, after-school babysitting often fell to my grandfather Henri. Together we built ancient Greek-style weaponry out of cardboard, made Bedouin tents in the living room, and, to the dismay of my parents, occasionally worked on carpentry projects involving a handsaw. But this was the first time that my grandfather, the former inventor, tycoon, and businessman, had ever suggested baking.

By saying those words, pain d’espagne, my grandfather seemed to have awoken a long-forgotten ghost, some ancestral spirit that I didn’t know was following me until that very moment. I knew all about my family’s life in Egypt, where my dad was born, and I had heard the stories about my family’s time in France and Italy before finally coming to the U.S. But I knew almost nothing about my family’s connection to Spain more than 600 years earlier; Spain felt to me, then, like an ancient country, one that did not appear on any map, a place nobody had ever been to, and yet here, in this little kitchen on Amsterdam Avenue, as if by some conjurer’s trick, my grandfather and I were going to reproduce the bread of Spain. It felt like a secret that everyone seemed to know about except for me. In retrospect, this might have been my first run-in with the entire notion of Sephardism. I still have the image etched into my memory of my grandfather standing over the detached stove, pouring batter into a pan, while I dreamed of what it would become.

I never got to taste it.

One of my parents came to pick me up, and by the time I returned a few days later, it was all gone. I, foolishly, thought it would be ready to eat right away, but my grandfather said that it needed to rise—il doit se lever. My grandfather lived another decade but never baked the bread again.

It is, apparently, according to relatives who have actually tasted it, a light, fluffy, yellowish cake with a firm but tender brown crust, cooked, usually, in a Bundt-like pan called a four Palestinien (Palestinian oven).

The mythological qualities of the pain d’espagne were not something I had merely imagined. Pain d’espagne is not a family specialty, but is, in fact, a very popular Sephardic sponge cake that dates back to the days long before the Inquisition. It rises in the oven not because of yeast, but because of eggs in the batter. In Italian it is called pan di Spagna, in Greek it is Pantespani, and in Ladino it is called pan d’Espanya. But according to chef Stella Hanan Cohen, author of Stella’s Sephardic Table: Jewish Family Recipes from the Mediterranean Island of Rhodes, the cake is also sometimes called pan esponjado—spongy bread—a phrase that sounds so much like all of the others yet means something completely different. The cake’s history is like tire marks that have been rubbed away and replaced by hundreds of years of other tire marks.

Because Spain is thought to have been home to one of the very first yeastless cakes in history—a quality that would have made it understandably popular with Jews around a certain holiday—pain d’espagne was able to easily embed itself into Sephardic tradition.

“When we entertain Spanish ambassadors at our house, they take a bite of the sponge cake and are moved to tears,” Cohen told me over the phone. “You’re making something that is a bite of ancient Spain.”

The story of pain d’espagne is the story of food in a diaspora; while traditions at the point of origin—Spain, in this case—often shift or vanish with time, in exile, they become codified, almost like religious rites. It is for this reason pain d’espagne has managed to remain an ordinary staple of Jewish cultures to be cooked across the Mediterranean and eventually with hyperactive school children on the Upper West Side, while Spanish diplomats will stand befuddled at Cohen’s dining table after tasting something that was known only to their ancestors.

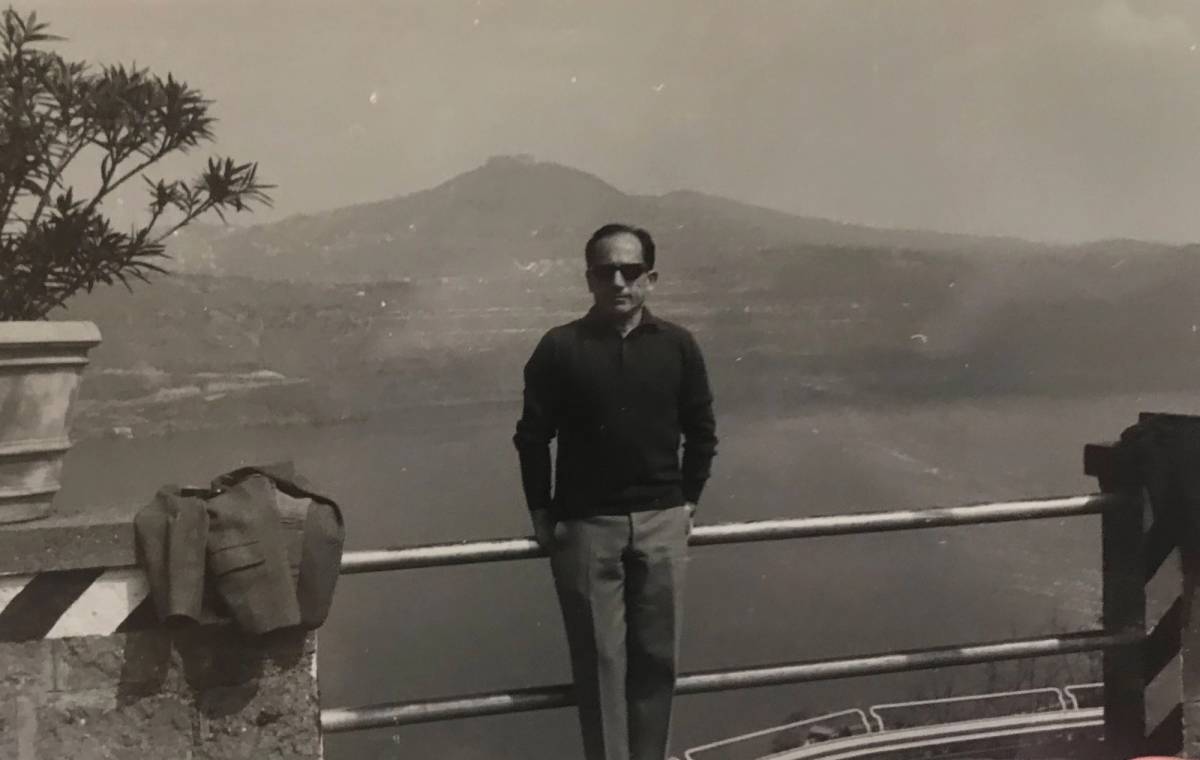

My grandfather Henri was not always an avid home baker. He was born in Istanbul when it was still Constantinople. At 17 he immigrated to Egypt, where he spent two years working in a flour mill. Later, he found work in a cotton factory, and eventually went on to own and operate the premier Egyptian cotton-dyeing plant and invented dyeing machines still in use today. In America, after my family’s expulsion from Egypt, his entire workshop had to be shrunk down to the size of a single kitchen drawer. Robbed of every last thing from his old life except his gray flannel suits, he turned once again to that craft he had learned at the age of 17. The engineer in him picked up the science of baking with ease, and as in all things he took on, he excelled in the artistry of it and mastered new techniques. No longer at the helm of a factory and responsible for designing industrial machinery, baking, like carpentry and Greek weapon-building, allowed him to exercise the muscles of invention and ingenuity once more, and the serenity of it seemed to become his way to pass the days and to restore some measure of order to a fractured life. It was a habit that should have presaged my own, given that I have inherited the compulsion of spending hours shaping pasta by hand and baking pizza when I am at my worst or most contemplative.

Trying to figure out exactly what my grandfather did on that autumn day almost 30 years ago, however, came with an additional complication; I distinctly remember his telling me that the bread had to rise. But if pain d’espagne is a famously unleavened cake, then what was he doing?

There are hundreds, if not thousands, of recipes for pain d’espagne online, some that use baking powder, some that don’t, some with cream of tartar, some with eggs whipped to stiff peaks, others to soft or medium peaks, some with lemon juice, some with orange juice, some broiled in the final stage with syrup. Not one of them has yeast in it.

The notion of the cake’s rise has stuck with me all these years like a shard of glass in my foot. It was the reason I never got to eat it. I might have forgotten that afternoon entirely if only I’d gotten to try the bread, but because of the rise, pain d’espagne has remained as elusive and enigmatic as that mystical name spoken by my grandfather.

I began to explore another possibility. Perhaps my grandfather had allowed the batter to set, rather than rise. Quickly, however, I learned that letting anything with whipped eggs sit for too long threatens the oven-rise altogether, which results in a flatter, denser cake.

Cohen told me that she’d never heard of any recipe that used yeast, or indeed of any sponge cake that needs time to rise.

But when I spoke with food writer Roy Yerushalmi, his answer was much more emphatic: “No. Absolutely not. Impossible. You don’t let pan di Spagna rise!”

Yerushalmi, however, who also grew up in a home that spoke no fewer than three languages, came up with another theory. He believed that I was not facing a culinary enigma, but rather, a linguistic one. Contrary to all logic, polyglots can be incredibly imprecise in what they say. In multilingual homes you are able to pick and choose words from various languages to weave together a tapestry of meanings, which can often lead to unintended misapprehensions, arguments, and, occasionally, a lifetime of culinary confusion.

It is just as likely that my grandfather intended to explain that the pain d’espagne needed to cool after it was baked, and he simply borrowed a word in another language to describe what bread does when one lets it chill out on the counter for a while. This was not an uncommon occurrence for a man who spoke French, Arabic, Italian, Greek, Spanish, Turkish, and, reluctantly, some English. Perhaps I’d finally found the answer to the mystery of the cake’s rise.

But then, when I least expected it, new information came to light.

Fans of The Great British Baking Show will perhaps recall the Savarin cake, a favorite of Paul Hollywood’s. One evening as the show played on in the background, I looked up at my screen and saw a fluffy, yellow cake similar in almost every way to a pain d’espagne, only with one major difference: yeast.

I sent a photo of a Savarin to my dad. That looks right, he replied. I felt a sudden rush. Then, for comparison, I sent a photo of a traditional unyeasted pain d’espagne. That also looks right, he said.

I realized then my only choice would be to bake cakes in both styles and see which of the two my father and uncle felt was closest.

I began cobbling together various aspects of different recipes based on what I thought my grandfather might have done. I knew that his dough very likely had honey in addition to sugar, given that he put honey in nearly everything. My father had also once mentioned that in the 1970s, Henri had found a way of making his sandwich bread tangier by adding orange juice to the dough. This, I realized, must have been a trick he learned from baking pain d’espagne, which meant that his recipe was likely one of the ones that had orange juice in it.

“Spain is prolific with oranges,” Cohen said. “Especially juicy oranges from Seville or Valencia.” But, given what was always in my grandparents’ fridge at the time, I refuse to believe that my grandfather used anything other than Tropicana Homestyle juice.

Early one unusually cold September evening that bore premonitions of that autumn afternoon decades ago, I put my first test batches of bread in the oven, thinking that in an hour I would be met with a cake that I’d been waiting all my life to taste. But roughly halfway through, I heard a noise coming from my kitchen—the distressing sound known to all cat owners of a vase or glass being tipped over. I rushed into the other room and saw that my oven door had exploded outward, sending shards of shattered glass all throughout my kitchen.

The cat was quickly exonerated, but both cakes were ruined.

In the many weeks that it took my New York City landlord to replace the oven, I found myself once again in a state of contemplative unrest such as I had found myself as a child waiting to return to my grandfather’s apartment to try the cake.

Time paved the way to restlessness. I mulled over my notes, I called and cross-examined my already exasperated relatives, I tried my best to imagine myself back in that kitchen on Amsterdam Avenue. And gradually, I started to doubt myself. Most recipes for pain d’espagne call for separating egg whites and yolks, and folding them together almost like a soufflé. But would my grandfather really have gone through the trouble, especially as an after-school project? I started dreaming up a recipe for a third cake that used whole eggs in the batter.

Soon, a new oven arrived. More cakes went into it. And this time, nothing exploded. An hour later, three golden brown cakes emerged. That evening I met my uncle for a walk, and standing under the canopy hiding from a sudden flash of autumn rain, I took out a Tupperware with three slices of cake in it.

The Savarin went first; a part of me must have thought he would light up and not even bother with the others. Instead he shook his head. Not right at all, he said.

Next, I broke off a piece from a slice with separated and folded egg whites. Again, he shook his head. A lovely cake, but far too springy.

Then I gave him the third. He paused a moment and studied the slice under the lamplight. It could use a little more orange, he said, but this is it.

And yet something about this did not entirely satisfy me.

I don’t know why exactly my grandfather chose to bake a cake with me that afternoon, or why, of all things, he settled on a pain d’espagne. Nothing about the unremarkable sponge cake I produced for my uncle on that rainy evening gave me an answer to this question, which I realized then may have been what I’d been grappling with all this time. This here was not the answer, but maybe only the beginning of the answer. Perhaps what stuck with me about that day—the first and last time we set foot in the kitchen together—was not a sense of unfinished culinary business, but instead a far more elusive thing, a glimpse into whatever it was that had snuck up on my grandfather that afternoon and compelled him to bake a cake with his grandson. A cake that he ate alone. My grandfather had opened a door to me that day, one that he shut almost just as quickly. But it wasn’t a door to Spain, or to some shared ancestral past, but a door to himself. Without knowing it, I had been searching for that door most of my life. Somehow I had mistaken it for a cake.

Alexander Aciman is a writer living in New York. His work has appeared in, among other publications, The New York Times, Vox, The Wall Street Journal, and The New Republic.