The Rebellion Against Rashi

New scholarship captures the fierce but failed attempt to dethrone Judaism’s preeminent biblical commentator

The Commentary on the Torah by Solomon ben Isaac (1040–1105)—also known as Shlomo Yitzhaki, or Rashi—stands out as the most widely studied, influential Hebrew Bible commentary of all time. It has shaped perceptions of the meaning of the Torah, Judaism’s foundational document, for over nine centuries. Leading Israeli scholar Avraham Grossman proposed that “with the exception of Scripture and the Talmud themselves, it is doubtful whether any other literary creation so greatly influenced the spiritual world of the Jew in the Jewish people’s many dispersions in later medieval times and even beyond as did Rashi’s Commentary on the Torah.” The biblicist Nahum Sarna states: “no other commentary on the Hebrew Scriptures in any language has ever attained comparable recognition, acceptance, and sustained popularity or similar wide geographic distribution, or ever equaled it in its profound impact on human lives.”

Rashi’s enormous share in Jewish destiny owes to the fact that he astonishingly managed to write “the classic commentaries on the two classics of Judaism”: the Bible, especially the Torah; and the Babylonian Talmud. Yet unlike Rashi’s talmudic commentaries, the Commentary on the Torah’s elevation to supreme stature never gained unanimous consent. Indeed, a wholly unexpected side of the story of the Commentary’s transformation into a Jewish classic has recently come to light: passionate resistance to it, at times given expression in rhetorically intense assaults.

The rebels against Rashi blamed his unpacking of the divine word for a multitude of sins. In some cases, they concluded that it amounts to nothing less than “nonsense” and “absurdity,” words that would be shocking—if not blasphemous—to many contemporary readers.

The authors of the anti-Rashi rebellion are obscure but the authorities who inspired them are not. Foremost among them was the great luminary of Sefardic rationalism, Moses ben Maimon (aka Rambam or Maimonides). In the critics’ arrant scorn for Rashi and veneration of Maimonides lies a tale of two Judaisms. While the critics’ anti-Rashi rebellion did not win the day, it is worthy of our attention as one of many roads not taken by Judaism on its journey to modernity.

Many factors must have commended Rashi’s Commentary over the ages, even leaving aside its author’s status as a devoted communal leader, towering scholar, and, of course, his singular reputation as the foremost commentator on the Talmud. The Commentary explained the Torah in concise and digestible language where some later commentators cultivated a more involved essayistic—or, alternatively, formidably recondite and laconic—style. The Commentary provided a more or less continuous running account of the Torah’s narratives and laws where many later commentators glossed the Torah only intermittently. The Commentary offered an exposition of the “written Torah” basically in harmony with—and indeed heavily indebted to—the interpretations found in the authoritative tomes embodying the “oral Torah.” What surely endeared the work most to Jews was Rashi’s inclusion of classical rabbinic teachings, collectively called Midrash, in his interpretation of the divine word.

Rashi’s deployment of rabbinic interpretations was hardly a matter of cutting and pasting. Instead, working at his easel, Rashi carefully selected, refashioned, moved, and otherwise adapted these ancient dicta—according to principles that remain highly contested—in a way that quietly allowed him to hoist his own colors, often giving voice to the plurality of views present within and across the great tomes of rabbinic literature.

Rashi indelibly reconfigured the way the Torah became etched in the minds of Jews, as well as the manner in which the midrashic corpus was transmitted. Many later readers would barely distinguish the words of scripture from Rashi’s rabbinic readings of them. Was Nimrod’s attempt to kill Abraham by casting him in a fiery furnace in punishment for smashing his father’s idols in the Torah or Rashi? One barely knew (it wasn’t), and to some it barely mattered. What is certain is that midrashic ideas like these were etched into Jewish consciousness. Rashi’s glosses became, in a word, the closest thing Judaism has to a canonical reading of the Torah.

The anti-Rashi rebels attest to the ‘Commentary’s’ status as a Jewish classic as much as its many untold admirers.

Yet the ascent of the Commentary met with resistance, even as it faced stiff competition for canonical supremacy in the form of rationalist reconfigurations of Judaism as they developed in Mediterranean seats of Jewish learning. In the field of Torah interpretation, the main rival and alternative was Abraham Ibn Ezra, an offshoot of the Sefardic school of biblical commentary during the famed “golden age.” More broadly, Moses Maimonides—who bestrode the nexus of Jewish law, theology, and biblical interpretation like a colossus—shaped religious allegiances and literary productions of countless scholars in Mediterranean seats of Jewish learning and beyond.

Maimonides wrote no running Torah commentary, though some argue that his sui generis Guide of the Perplexed is best understood as a work of biblical interpretation. Many saw the exegetical methods that he pioneered, and the theological ideas that they legitimated, as salvific breakthroughs (or recoveries); others, as a foreign accretion fraught with mortal danger for the survival of authentic Judaism. For exegetes of a philosophical outlook, Maimonides stood as a totem due to his powerful effort to demonstrate the basic congruence between the words of the Torah and finalities of scientific truth.

In light of such convictions, it is little wonder that a tendency arose to put Rashi and Maimonides into direct opposition in a variety of ways, though the two never met except in Jewish legend. Over time, modern historiography joined this tendency to cast Rashi and Maimonides as foils, if not near-ontological antitheses. For example, the mid-20th-century historian, Judah Rosenthal, speaks of two “utterly opposing tendencies in our spiritual history,” one “romantic-conservative” fathered by Rashi and another “rational-progressive” by Maimonides, with an “epic battle” ensuing. While short on nuance, this understanding captures well some of the energy and vision that informed the rationalist rebellion against Rashi’s Commentary.

The fact that the Commentary was subjected to criticism is not news. Perhaps the best example, if not always sufficiently appreciated as such, is the critical scrutiny that it received from another son of Sefarad, R. Moses ben Nahman (aka Nahmanides; Ramban), who wrote a Torah commentary in which Rashi figured consistently.

While generally retaining a respectful tone toward Rashi (he calls him “Rabbi Solomon”), Ramban issued many trenchant criticisms of Rashi’s interpretations. What has only recently been excavated, however, is a record of unknown assaults on the Commentary made in the spirit of Ibn Ezra and the rationalist titan Maimonides that is so rhetorically fierce it could only have made Nahmanides quake.

Rashi’s “resisting readers” (to invoke a coinage from feminist criticism) poured opprobrium on the Commentary for two basic failings: its surfeit of misguided interpretation, especially of the rabbinic (midrashic) variety, and any number of scandalously unscientific ideas that Rashi interwove into the fabric of the divine word. The earliest datable figure to adopt a stance of derision toward Rashi is Eleazar Ashkenazi, a 14th-century scholar whose Torah commentary Revealer of Secrets apparently emerged from the veritable babel of Jewish intellectual and literary expression found in the late medieval Eastern Mediterranean. The recently recovered work remains to be digested, having languished for decades in Moscow among artifacts and literary treasures looted by the Nazis and intercepted by the Red Army after World War II.

What is clear is that unlike prior critical interlocutors of Rashi such as Nahmanides, Eleazar deploys a weapon against the Commentary that lacks precedents: mockery. In so doing, he can be seen as a precursor of modern critics of Orthodoxy during the Enlightenment. Eleazar’s harnessing of the potentially rebellious force of laughter and ridicule serves as a means for expanding the community of Rashi’s derisive naysayers.

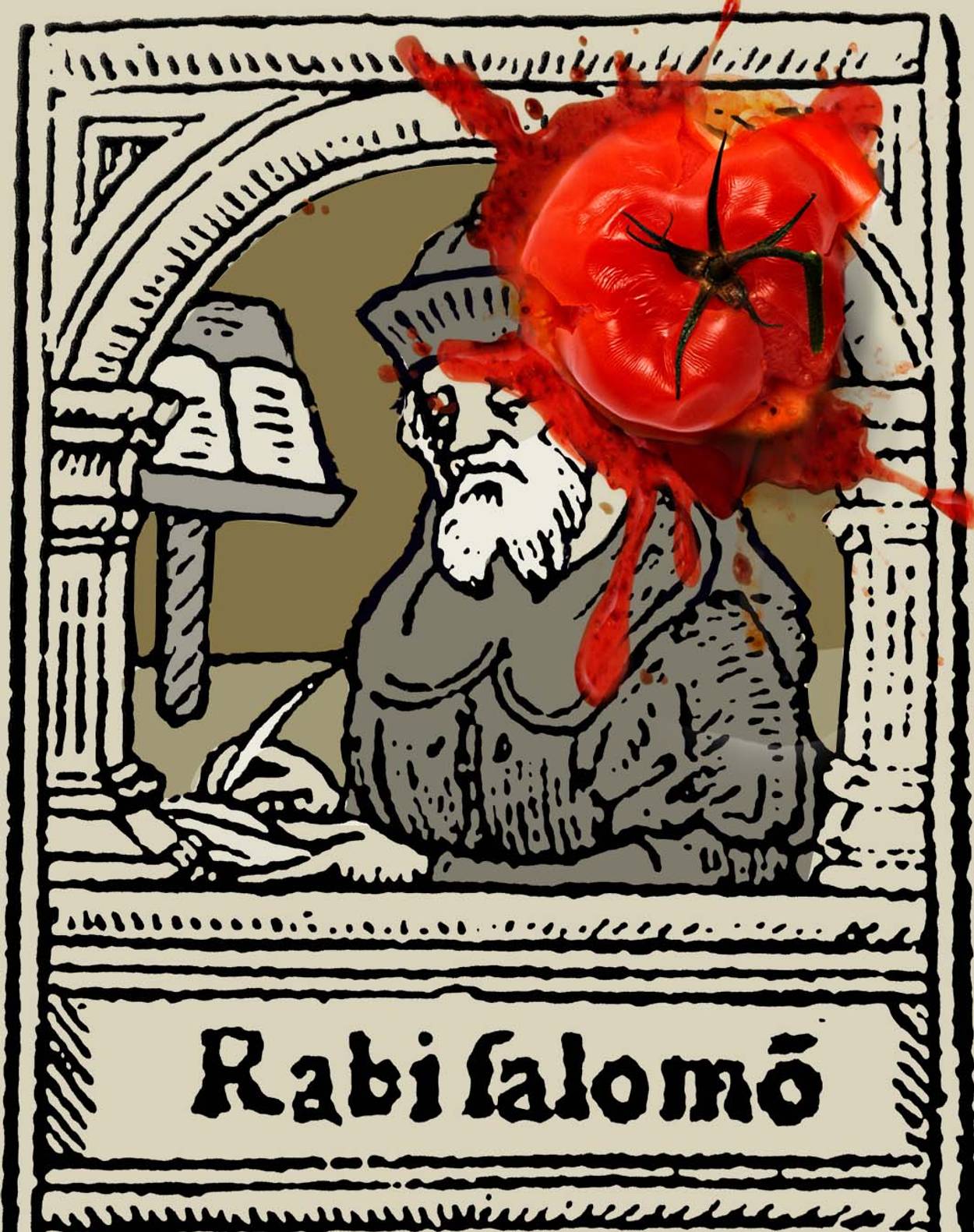

Those naysayers included the anonymous author of the most concentrated attack on the Commentary ever composed. This writer’s work comes down under a bulky title: The Book of Strictures in which Rabbi Abraham ben David Censured Our Rabbi Solomon the Frenchman (May His Memory Be a Blessing) Regarding the Commentary on the Torah. As its title suggests, it comprises a litany of strictures (hassagot in Hebrew) in which the author casts aspersions on selected interpretations of Rashi.

To cover his tracks, this fierce critic of Rashi wrote under the name of the towering 12th-century southern French talmudist permanently associated with the stricturalist genre, Abraham ben David of Posquières (known by his rabbinic acronym Rabad). Throughout his work, Pseudo-Rabad insistently contrasts an understanding of scripture grounded in canons of plain sense interpretation and scientific criteria of credibility with Rashi’s more fanciful midrashic methods and fantastical mentality.

A later reader of the Book of Strictures expressed outrage at the work’s disparaging treatment of Rashi and his biblical scholarship by mutilating the sole manuscript in which the work survives. The first page of these acts of defacement is illustrated on the cover of my recent book. The censor strikes out such things as the author’s description of Rashi as “devoid of any sort of wisdom save for [facility in] navigation of the talmudic pericope alone” and promises to expose places where Rashi “blundered.”

In short, the provocation of the Commentary’s success along with fear for the future should the Judaism of the Commentary continue to be broadcast brought some of the work’s critics to unheard of levels of vitriol. The rhetorical extremes of late medieval criticisms of the Commentary are in no way incidental to their authors’ aim to reduce not just Rashi’s exegesis but his Jewish vision to an inferior estate.

Another critic of Rashi who wrote under a false name was “Rabbi Palmon ben Pelet,” described as “a son of ‘Anonymous,’ who married a daughter of ‘So-and-So.’” In his Book of Accusations, this author put satirical genius in the service of exposure of the obscurantism that, in his view, came to degrade Jewish life in post-talmudic times. The corruption infiltrated every sphere, and this writer thought the Commentary a major cause and symptom of it. Indeed, only Rashi is attacked by name in his tract aimed at mounting a rationalist counterinsurgency. This aim seemingly helps to explain the work’s authorial mask of “Palmon ben Pelet.” The alias summons an insurrectionist movement by hearkening to On ben Pelet, a member of the biblical desert rebellion against Moses and Aaron.

Assessing the role of differing modes of biblical scholarship in creating the religious wreckage, the author subtly contrasts the midrashic hermeneutic of Rashi with the approach of Maimonides. Rashi’s interpretations are not actually “explanations” (perushim), he posits. Rather, they are midrashim that were never intended to be used for interpretive purposes. Explaining this thought in a commentary he wrote on his own work—written under yet another pseudonym, “Joseph ben Meshulam”—the author describes midrashim as “poetical conceits,” a definition found in Maimonides’ Guide of the Perplexed. Wherever Rashi is read, says the author, “the children of Israel find themselves stripped of the Torah’s and scripture’s plain sense.”

There is more. Beyond the Commentary’s injurious impact as an assemblage of misguided interpretations, Rashi’s scriptural magnum opus is “a cause of blindness and confusion with respect to the perfection of souls.”

In writing those words, the author of the Book of Accusations must have had in mind Maimonides’ intellectualist vision of human perfection. So understood, the Commentary’s popularity is even more deleterious than meets the eye. Threatened is the very purpose of revelation, as Rashi abets the falling away from rationality that our author sees as the root of the Jewish people’s spiritual malaise and ongoing political enfeeblement in exile.

This critic of Rashi again points to a struggle for the future of Judaism and the soul of the Jewish people in which Rashi’s Commentary is understood to play a decisive, catastrophic role. The Book of Accusations expresses alarm at the growing ubiquity of Rashi’s writings while seeking to enthrone his own superior alternatives, most notably in the form of the figure whom he calls the supreme “master and guide,” Maimonides, cast by the author as a divine emissary in the manner of his biblical namesake, Moses. Were the nation to return to Maimonides, ancient glories could be restored. Instead, the Commentary’s increasing popularity reinforces the very trends that have brought the Jewish people to spiritual wrack and ruin.

To speak in these terms is to emphasize a side of the Commentary’s legacy that has received relatively short shrift: its role not only as a biblical commentary of the first rank but also as a rich source of ideas that, through Rashi’s careful selection and at times decisive reformulation, shaped Jewish sensibilities and perceptions of the Torah’s teachings. The implication is that Rashi’s commentarial voice must be appreciated not only for its exegetical intentions and achievements but also in terms of the teachings that it set forth, allusively and elusively, by way of rewritten Midrash.

The Commentary was, of course, a commentary, but it can also be seen as an important work of thought—one, to quote the great contemporary scholar of Judaism Michael Fishbane, true to the “inner texture of classical Jewish thinking as an ongoing exegetical process.” The clash between Rashi and his critics often amounts to a fundamental dispute over the matter and modes of Torah, pitting a reading informed by quasi-mythical midrashic ideas involving frequent miracles and routine divine interventions in human affairs against a scientific understanding rooted in nature’s intelligible workings as known from the everyday world.

Rashi’s Commentary became deeply and diversely embedded in Jewish life and has remained so, but modernity’s disintegrative and fragmenting effect has taken its toll, meaning one can find signs in recent centuries of the work’s decanonization. We may illustrate this side of the story on the basis of the essay published by an amateur Bible scholar in 1953 which calls Rashi’s interpretation of the Bible “very important” but immediately adds that it is “only the commentary of Rashi.”

Thus did David Ben-Gurion insist that Rashi should make no special claim on Jews and, speaking more broadly, that he suffered from a defect from which all commentators suffered prior to the Jewish return to Zion. Through no fault of their own, such expositors of the Tanakh could not connect with the “spiritual and material climate of the Bible” in a way that was necessary to arrive at the Bible’s “essence and truth—historical and geographic as well as religious and cultural.” Alan Levenson remarks that in such statements Ben-Gurion was drawing lines of battle: “On the one side, Zionist, Israelocentric, biblical; on the other, Orthodox, diasporic, and rabbinic.” For Ben-Gurion, Rashi fell squarely in the latter category.

Yet despite clear signs of its marginalization, there are corresponding indicators of the Commentary’s abiding contemporaneity. Already in his Yiddish poem of 1890, “Akhdes” (“Unity”), Morris Winchevsky, a student at the yeshiva in Vilna who became an atheist and socialist, expressed in passing the Torah’s inseparability from Rashi’s commentary in the Jewish collective imagination: “We’re all brothers. ... Religious and leftists are all united, like groom and bride ... like Humash and Rashe [Rashi], like kugel and kashah.” In his address upon receiving the Nobel Prize, Israeli writer S.Y. Agnon listed as the works that influenced his writing “first and foremost” the Bible, Mishna, Talmud, Midrash, and “Rashi’s commentary on the Bible.”

Fast forward to the assessment of the Commentary in a five-volume edition of it produced under the “Artscroll” imprint of Mesorah Publications, whose creators sponsor a spectacularly successful line of Jewish classics produced in at once user-friendly and elegant and uncompromisingly ultra-Orthodox formats. The editor states that the “messages implied by the nuances of Rashi are infinite,” such that readers of the Commentary should approach it with the same attitude that “Rashi himself adopted towards Scripture,” namely that “not the slightest aspect is arbitrary.” In short, as a text that itself requires the most profound and penetrating interpretation, the Commentary is elevated almost to the level of scripture itself. Meanwhile, engagement with the Commentary extends to digital platforms, with the work produced on websites in editions based on manuscripts or analyzed though distribution lists that offer a “dose” of the work by way of “Rashi newsletters.”

In a way, the anti-Rashi rebels attest to the Commentary’s status as a Jewish classic as much as its many untold admirers. One generally does not waste time or intellectual energy excoriating a work that one thinks irrelevant and uninfluential. Consider that it is Rashi’s biblical commentary that David Ben-Gurion felt compelled to contest; no other commentator is mentioned. In every act of attempted decanonization lies tacit recognition of a work’s hold on a community. By all indications, that hold, and the Commentary’s remarkably enduring capacity to provide major segments of world Jewry with what nowadays we call their “narrative,” is assured for a long time to come.

This essay is adapted from several chapters of Rashi’s Commentary on the Torah: Canonization and Resistance in the Reception of a Jewish Classic, by Eric Lawee, with permission of Oxford University Press.

Eric Lawee is a professor of Bible at Bar-Ilan University where he holds the Asher Weiser Chair for Research into Medieval Jewish Biblical Interpretation.