Nazi Antisemitism & Islamist Hate

A review of recent scholarship on the shaping of the modern Middle East in the aftermath of the Holocaust, and how Islamist hate has roots in Nazi antisemitism.

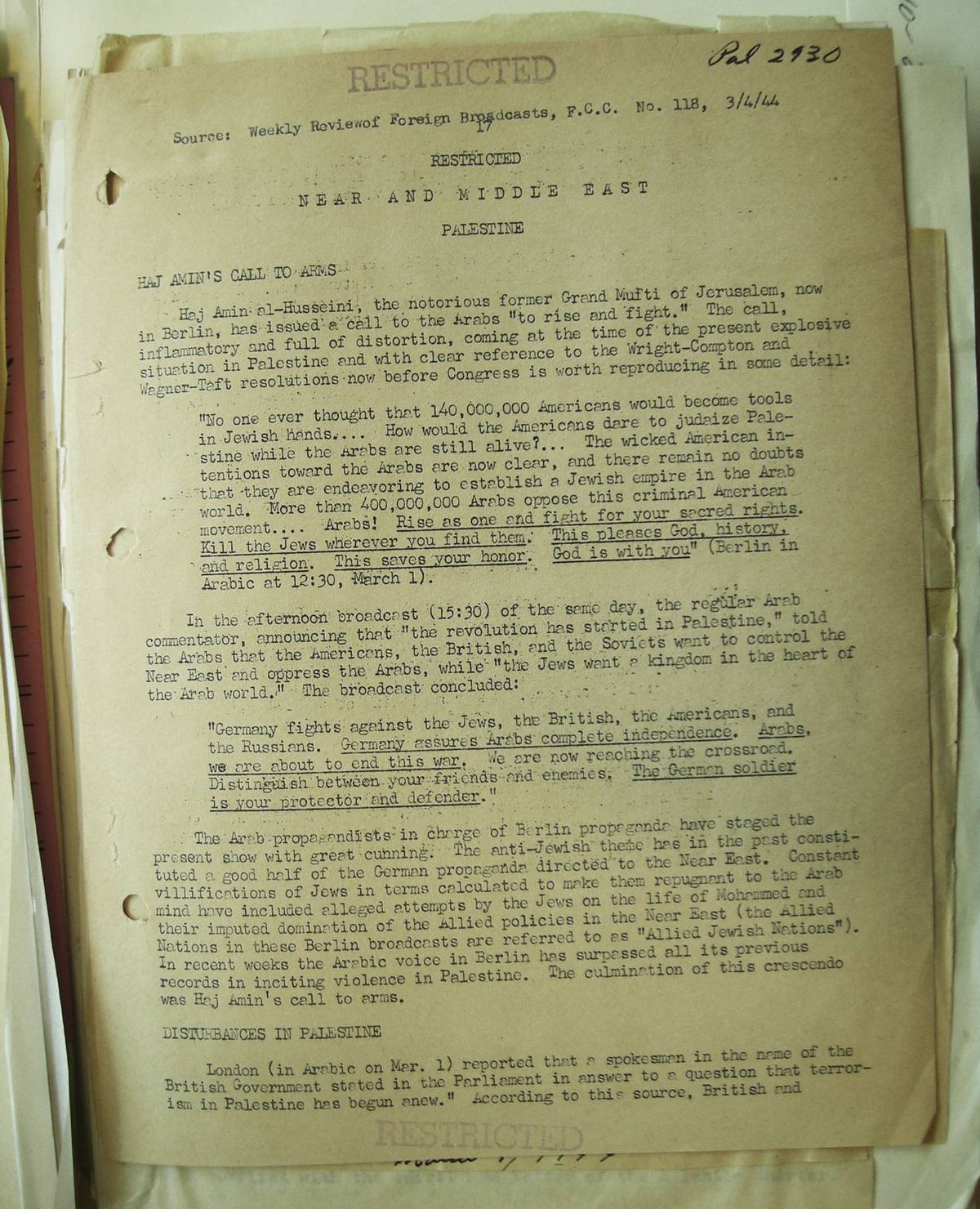

In early June 1946, Haj Amin el-Husseini, also known as the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem, escaped from a year of pleasant house arrest in France and flew to Cairo. Husseini, by then often referred to in Egypt simply as “the Mufti,” was internationally renowned as a collaborator with Nazi Germany as a result of his meeting with Adolf Hitler in Berlin in November 1941, and his Arabic language tirades to “kill the Jews” broadcast to the Middle East on the Third Reich’s shortwave radio transmitters. Husseini was a key figure in an ideological and political fusion between Nazism and Islamism that achieved critical mass between 1941 and 1945 in Nazi Germany, and whose adherents sought to block the United Nations Partition Plan to establish an Arab and a Jewish state in former British Mandate Palestine, helping to define the boundaries of Arab politics for decades thereafter.

On June 11, 1946, Hassan al-Banna, the leader of the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt, penned the following welcome home to Husseini:

Al-Ikhwan Al-Muslimin and all Arabs request the Arab League on which Arab hopes are pinned, to declare that the Mufti is welcome to stay in any Arab country he may choose, and that great welcome should be extended to him wherever he goes, as a sign of appreciation for his great services for the glory of Islam and the Arabs. The hearts of the Arabs palpitated with joy at hearing that the Mufti has succeeded in reaching an Arab country. The news sounded like thunder to the ears of some American, British, and Jewish tyrants. The lion is at last free, and he will roam the Arabian jungle to clear it of wolves.

The great leader is back after many years of suffering in exile. Some Zionist papers in Egypt printed by La Societé de Publicité shout and cry because the Mufti is back. We cannot blame them for they realize the importance of the role played by the Mufti in the Arab struggle against the crime about to be committed by the Americans and the English …The Mufti is worth the people of a whole nation put together. The Mufti is Palestine and Palestine is the Mufti. Oh Amin! What a great, stubborn, terrific, wonderful man you are! All these years of exile did not affect your fighting spirit.

Hitler’s and Mussolini’s defeat did not frighten you. Your hair did not turn grey of fright, and you are still full of life and fight. What a hero, what a miracle of a man. We wish to know what the Arab youth, Cabinet Ministers, rich men, and princes of Palestine, Syria, Iraq, Tunis, Morocco, and Tripoli are going to do to be worthy of this hero. Yes, this hero who challenged an empire and fought Zionism, with the help of Hitler and Germany. Germany and Hitler are gone, but Amin Al-Husseini will continue the struggle.

Al-Banna, himself an ardent admirer of Hitler since he first read Mein Kampf, then compared Husseini to Muhammad and Christ.

When al-Banna wrote his panegyric to Husseini, the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt had a membership approaching 500,000 sympathizers and was the world’s leading Islamist organization. The Brotherhood sought to establish a state based on Shariah. It proposed to abolish political parties and parliamentary democracy. It called for nationalization of industry, banks, and land. It proposed an Islamist version of national socialism and anti-communism, and waged cultural war for male supremacy against sexual freedom and equality for women. It led the cry of opposition to the Zionist project in Palestine with language that made no distinction between antisemitism and anti-Zionism. It was recognized at the time by the Egyptian left as a reactionary if not fascist organization. Hence, al-Banna’s praise for the Nazi collaborator Husseini was not at all surprising for his liberal and left-leaning contemporaries.

After four decades of Soviet and PLO propaganda during the Cold War, then another four decades of Islamist propaganda from the government of Iran and organizations such as Hamas and Hezbollah, the reactionary and antisemitic core of the Muslim Brotherhood and the ideas of al-Banna and Haj Amin el-Husseini have, for many, been lost from view, were never known in the first place, or are dismissed as musty historical details. Yet al-Banna’s statement that Husseini would “continue the struggle” that Hitler had waged against the Jews and Zionism proved correct. As leader of the Arab Higher Committee in Palestine, Husseini did “continue the struggle” against the Jews by insisting on war in 1947 and 1948 in order to prevent Israel’s establishment, and by fueling the fusion of Islamism and Palestinian nationalism that would make rejecting the fact of Israel’s existence a core principle of Arab politics for the next half-century.

In the past 30 years, historical scholarship has confirmed what American liberals and leftists, French socialists, communists, and Gaullists, and communists in the Soviet Union, Poland, and Czechoslovakia understood at the time. The realities of Palestinian nationalist collaboration with the Nazis were a matter of public knowledge and opprobrium around the world in the immediate postwar years, when American liberals in Congress, such as Sen. Robert F. Wagner and Congressman Emanuel Celler, the editors of The Nation magazine, the leftist dailies PM and the New York Post, and leaders of the American Zionist Emergency Council, as well as Simon Wiesenthal in Vienna, published documents from German government files offering compelling evidence of Amin el-Husseini’s enthusiasm for the Nazis and his visceral hatred of Judaism, Jews, and the Zionist project. These leaders and publications urged Britain, France, and the United States to indict “the Mufti” for war crimes, but the three governments, with Arab sensibilities in mind, refused to hold a trial that might have ended his political career. His “escape” from a year of house arrest by the French government in June 1946 and return to a hero’s welcome in Cairo and Beirut was part of a larger loss of memory in the West about the crimes of Nazism that accompanied the early years of the Cold War.

The realities of Palestinian nationalist collaboration with the Nazis were a matter of public knowledge and opprobrium around the world in the immediate postwar years.

In recent decades, the views of journalists and political figures in the New York of the 1940s have found confirmation in scholarship by historians in Britain, Germany, Israel, and the United States. Working in American, British, French, and German government archives, and with Arabic-language texts, they have produced further evidence of the significant role collaboration with the Nazis played in shaping the founding ideas of the Muslim Brotherhood and of Palestinian Arab rejectionism.

Yet following the Soviet turn against Israel during the antisemitic “anti-cosmopolitan” purges of 1949-56, the Soviet bloc and then the Palestine Liberation Organization succeeded in convincing much of international leftist opinion that these connections never existed or were insignificant. Hence the PLO, having obscured the Nazi connections of its founding father, was able to reinvent itself as an icon of leftist anti-imperialism. While some Arab states have themselves moved away from the toxic mixture of Islamism, anti-Jewish hatred, and Palestinian nationalist rejectionism that al-Banna and Husseini implanted, their campaigns have had a continuing impact in Western universities, where they serve as the ideological foundation of academic anti-Zionism and the resulting BDS campaigns of recent decades, which have aligned the Western left with the afterlife of Hitler’s Nazi Party and its larger designs for the Middle East.

The refusal to indict Amin el-Husseini and put him on trial for the war crimes he committed through his rigid allegiance to the Nazi state constituted an enormous, missed opportunity to draw public attention to the ideological sources of Arab rejection of the Zionist project. This formative history was not entirely neglected. In 1965, Joseph Schechtman, who had worked in New York with the American Zionist Emergency Council in the immediate postwar years, published The Mufti and the Führer: The Rise and Fall of Haj Amin el-Husseini, a work that exposed the Nazi collaboration of the leaders of the Palestinian Arabs. In 1986, historian Bernard Lewis focused scholarly attention on this issue in Semites and Antisemites: An Inquiry into Conflict and Prejudice. Despite the quality of their research, these works received only minimal attention from historians of the Nazi regime. Far more influential was Orientalism, the work of Columbia professor of literature Edward Said, which succeeded in pushing aside the evidence of the historians and presenting the Palestinian Arabs as innocent victims of Western imperialism and colonialism.

In 1988, with the publication of Klaus Gensicke’s Der Mufti von Jerusalem, Amin el-Husseini, und die Nationalsozialisten by Peter Lang Publishers in West Germany, scholarship on Husseini’s collaboration with the Nazi regime took a significant step forward. The book was originally Gensicke’s 1987 doctoral dissertation, completed at the Free University in West Berlin, which unfortunately did not lead to an academic career at one of Germany’s universities. It was published again in 2007 in Germany, and in English in 2011 by Vallentine Mitchell in London.

Gensicke’s pioneering research offered the first exploration of Husseini’s role based on the declassified archives of the German Foreign Office, the headquarters of the SS, the Reich Security Main Office, and the Nazi Propaganda Ministry. As a result, he was able to offer far more detail about the depth of Husseini’s enthusiasm for Hitler and the Nazis, including his close working relationships with officials in the German Foreign Office; contributions to Nazi propaganda; collaboration with Heinrich Himmler and the SS, especially in Yugoslavia; details about monthly financial support he received from the Nazi regime; and textual evidence of the depths of his hatred of Judaism and Jews, which underlay his hatred of the Zionist project.

Der Mufti von Jerusalem revealed that Husseini told German Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop that the Arabs were “natural friends of Germany because both are engaged in the struggle against their three common enemies: the English, the Jews and Bolshevism.” Husseini offered to assist the Nazi war effort with intelligence cooperation and sabotage operations in North Africa. Gensicke included details of Husseini’s famous meeting with Hitler of Nov. 28, 1941, during which Hitler promised that when the German armies reached the southern edge of the Caucasus, he would aim at the destruction of the Jews of North Africa and the Middle East, and he would appoint the Mufti to be spokesperson of the Arab world. Gensicke revealed Husseini’s cooperation with German intelligence officials, his enthusiasm for General Erwin Rommel’s military victories in spring and summer 1941 in North Africa, and his efforts to establish a German-Arab legion, as well as a Bosnian Muslim SS Division in Yugoslavia. In 1988, his German language audience could read that on Dec. 11, 1942, Husseini wrote to Hitler to praise “close cooperation between the millions of Muslims in the world and Germany with its Allies in the Tripartite Pact, that is directed against the common enemies, Jews, Bolsheviks and Anglo-Saxons, will with God’s help lead to a victorious outcome of this war for the Axis Powers.”

Der Mufti von Jerusalem included key passages of Husseini’s speech at the opening ceremony of the Islamic Institute in Berlin on Dec. 18, 1942. In it, as reported by the Arabic-language radio and in the German-language press, he declared that the Jews had been enemies of Islam since the days of Muhammad and asserted that they ruled the United States as well as godless communism in the Soviet Union. World War II, he said, had “been unleashed by World Jewry.” At the Islamic Institute on Nov. 2, 1943, Husseini cited passages in the Koran to assert that divine anger was aimed at the Jews. Gensicke revealed that Husseini had urged governments in Eastern Europe not to allow Jews to leave Europe for Palestine. Instead, Husseini suggested that they be “relocated” to Poland and placed under what he called “active surveillance.” In so doing, Gensicke brought the attention of his German readers to the findings of a 1947 report by the Nation Associates on the Arab Higher Committee, as well as to Schechtman’s The Mufti and the Führer. He cited evidence that Husseini had worked closely with Heinrich Himmler in training imams who would work with the Bosnian SS division and with Muslim soldiers fighting with the Nazis on the eastern front, and that the Nazi regime paid Husseini 90,000 marks a month from 1942 to 1945.

After the publication of Der Mufti von Jerusalem und die Nationalsozialisten, scholars, journalists, writers, and an interested public in Germany had abundant evidence to confirm the links between the founding leader of the national movement of the Palestine Arabs and the Nazi regime during the years of World War II and the Holocaust, and of the central role that Husseini’s interpretation of Islam played in his politics. Yet Gensicke’s pathbreaking work was published at a time when the romance surrounding the Palestinian movement and views of Israel as a recurrence of fascism still found advocates on the West German left. It had modest if any impact on scholarship in Germany or elsewhere.

Al-Qaida’s attacks on the United States on Sept. 11, 2001, sparked renewed interest in continuities and breaks between Nazism and Islamism. Osama bin Laden’s hatred of Jews, Judaism, and Israel was unambiguous and, for his associates and followers, a source of pride. The month after the attacks, I wrote an article describing al-Qaida as a phenomenon of the extreme right, an example of “reactionary modernism,” a term I had found useful in describing the German right and the Nazis. Yet al-Qaida’s blend of modern conspiracy theory and religious citations of Islamic texts remained to be explored. In 2003, two of the West’s finest intellectuals, Paul Berman in Brooklyn and Matthias Küntzel, living north of Hamburg, published pathbreaking books that connected fascism and Nazism in Europe’s past with the Islamist terrorists of the turn of the century.

In 2003, Ca Ira, a small left-liberal press in Freiburg, published Küntzel’s Djihad und Judenhass: Über die neuen antijüdischen Krieg (Jihad and Jew-Hatred: On the New Anti-Jewish War). It was a second turning point in this discussion, combining new research as well as a synthesis of previous scholarship. Küntzel brought Gensicke’s findings to the attention of Ca Ira’s liberal and left-liberal readership. In his epilogue, Küntzel noted that none of the scholarly journals of history and politics in Germany had reviewed Gensicke’s work. Though it addressed issues central to a topic of great public interest—the conflict between Israel and the Palestinian Arabs—the German press and media ignored it as well. So did many scholars of the Middle East. Or, if they did discuss the book, they refused to face the full implications of the evidence Gensicke had presented.

Küntzel attributed this neglect to “the fact that it is Israel, more than any other country, which provokes the German left as reflexively to make comparisons with National Socialism,” a habit that had “to do with the specific needs of Germans for identification and projection.” First the radical left of the 1970s, then increasingly mainstream politicians, made the Nazi analogy to fulfill an “unconscious wish for unburdening” of the German past. Küntzel wrote that “knowledge of the connection, embodied in the Mufti, between the Palestinian national movement and National Socialism would complicate the [German left’s] identification with the Palestinians as well as the projection of the German policy of extermination onto Israel.” The result was denial or minimization of the connection between the Palestinian national movement and National Socialism.

The publication of Küntzel’s Djihad und Judenhass in 2003 succeeded in making Gensicke’s findings meaningful to a broader audience by connecting historical scholarship on Husseini and other Arab Nazi collaborators to the “aftershock” of the political consequences of their wartime collaboration in the Middle East after 1945. He did so in the spirit of the liberal tradition of Aufarbeitung der Nazivergangenheit, “coming to terms with the Nazi past.” Küntzel argued that examination of the connection between the Nazis and Arab collaborators and its post-World War II aftereffects was a central demand of an honest reckoning with the crimes of the Nazi regime, and of an effective fight against contemporary antisemitism. The work gave considerable attention to the role of the Muslim Brotherhood as the organizational weapon that transformed Islamist ideology into political action.

Küntzel’s book burst into the consciousness of a broader liberal public in 2003 in part because it helped explain the ideological origins of the attacks on the United States on 9/11. Teaching at a vocational college in Hamburg, Küntzel followed the investigations and trial of those who assisted “the Hamburg cell” of Islamist terrorists that had conducted the attacks. As the 9/11 murderers denounced Jews, the United States, and Israel, it became obvious that they were repeating conspiracy theories blending the anti-Jewish hatreds that had abounded in the ideology and propaganda of the Nazi regime with the anti-Jewish hatreds expressed by Husseini and the Muslim Brotherhood in the 1930s and 1940s, and by later Islamist offshoots from Hamas to al-Qaida. Djihad und Judenhass brought to the fore, in public as well as scholarly discussion, the link between Nazism and Islamism which had been forgotten, repressed, or never known in West German leftist discourse. It restored the phrase “anti-fascism” to its original meaning and shattered efforts of the radical left to tar the Jewish state with the “fascist” label.

In addition to bringing Gensicke’s findings to a broader audience, Küntzel drew further attention to the Nazis’ shortwave Arabic-language radio broadcasts, the echoes of their themes in the ideology of the Muslim Brotherhood, and their role in justifying the Palestinian Arabs’ rejection of any compromise with the Zionist project. He traced the ideological lineages of Nazism and the Muslim Brotherhood to the Hamas Charter of 1988, and then to the founding of al-Qaida. Küntzel wrote that 9/11 was a chapter of “the new anti-Jewish war”—a profoundly reactionary phenomenon whose predecessors were the ideologies of fascism and Nazism.

Al-Qaida’s Nazi lineage through the Muslim Brotherhood showed that the 9/11 attackers were not leftist anti-imperialists. Rather, they were a product, in part, of the continuing aftershock of Nazism in the Middle East. Nazism, which ended as a major political factor in Europe with defeat in 1945, had enjoyed a robust afterlife in the Muslim Brotherhood and its offshoots, such as Hamas and al-Qaida, which had culminated on 9/11 in an attack on the West, motivated in large part by antisemitic conspiracy theories.

But the post-World War II tradition of Islamist antisemitism that inspired first the civil war started by the Arab Higher Committee in Palestine in December 1947, and then the Arab state invasion of Israel in May 1948, was not only or even primarily the result of the impact of Nazism, of course; it had deep indigenous cultural, religious, and political roots as well. Nazi Germany’s Arabic-language broadcasts in North Africa and the Middle East during the war fused antisemitism and opposition to the Zionist project with Nazi ideology and Islamist themes. Yet Husseini’s texts, some of which were available in German-language publications and in Gensicke’s work, indicated that the embrace of Nazism was neither a coincidence of timing nor only an alliance of convenience. Rather, Husseini’s hatred of Judaism and the Jews was the source of his attraction to Nazism, and then of his rejection of the Zionist project. This “Jew-hatred”—Judenhass—was the ideological passion that Husseini shared with Hitler and Himmler. Husseini and other Arab exiles brought their hatred of the Jews and Judaism with them when they came to Berlin in 1941, and they brought those same hatreds—now fused with the additional element of Nazism—back to the Middle East after World War II.

In 2007, Russell Berman, professor of comparative literature at Stanford and editor of Telos, a quarterly journal of social theory, published an English edition of Küntzel’s book with the title Jihad and Jew-Hatred: Islamism, Nazism, and the Roots of 9/11. Now, the English-speaking world had at its disposal a succinct account of the continuities from the Nazis’ “anti-Jewish war” to the decisions of the Arab Higher Committee. Küntzel argued that it was the ideological mixture of Nazism and Islamism that was the most important causal factor which led leaders of the Palestinian Arabs to reject the United Nations partition resolution of Nov. 29, 1947. He noted that Western governments, including the United States, had refused to bring this issue to the fore, primarily in order not to antagonize the Arab states during the early months and years of the Cold War.

In the United States in 2003, Paul Berman published Terror and Liberalism, an equally important book about Europe’s totalitarian past and Islamism. Berman did not focus on the leaders of the Palestinian Arabs or on Haj Amin el-Husseini’s Nazi collaboration, but rather on the writings of the leading ideologue of the Muslim Brotherhood, Sayyid Qutb. Berman grasped with clarity and eloquence the parallels between Nazi and fascist totalitarianism in Europe’s mid-20th century and Qutb’s reactionary attack on liberalism, the Jews, the United States, and Israel in his commentaries on the Koran and Islamic commentaries about the Koran. Qutb shared with Husseini the conviction that the religion of Islam was in its essence hostile to Judaism and the Jews, and therefore to a Jewish state in Palestine.

Qutb, like Husseini, offered a paranoid construct of an Islam under attack by Jews, Christians and modern culture, and a resulting program of counterattack that celebrated death and martyrdom in an effort to create a pristine Islamic state in which state and religion would be fused and liberal modernity banished. In Qutb’s justification, and then in bin Laden’s practice of terror, Berman saw a reproduction in Islamic terms of the totalitarian aspirations that fueled Nazism and fascism in 20th-century Europe. “Not every exotic thing,” he wrote—such as suicide bombers, visions of utopia achieved through terror, and of a fractured world made whole and good through apocalyptic violence—was “a foreign thing.” Terror and Liberalism, like Djihad und Judenhass, made the case that the intellectual explication and denunciation of Islamist antisemitism should be a distinctively, if not exclusively, liberal endeavor. In 2006, Walter Laqueur’s synthetic study, The Changing Face of Antisemitism: From Ancient Times to the Present Day, discussed the shift of the center of global antisemitism from Europe to the Middle East.

Knowledge of Nazi policy toward the Muslim world took another step forward in 2006 when professors Klaus Michael Mallmann and Martin Cüppers published Halbmond und Hakenkreuz: das Dritte Reich, die Araber und Palästina (Crescent and Swastika: The Third Reich, the Arabs and Palestine). The English edition was published in 2010 as Nazi Palestine: The Plans for the Extermination of the Jews. Mallmann was the director and Cüppers an associate of the University of Stuttgart’s Center for Investigation of Nazi Crimes in Ludwigsburg, Germany. Their research in the archives of the Nazi regime revealed for the first time that Hitler and Himmler had created an SS “action group” (Einsatzgruppe) that was prepared to go to North Africa in 1942 in the event of German military victory there in order to extend the Final Solution to the approximately 1 million Jews living in North Africa and the Middle East. Mallmann and Cüppers demonstrated that the propagandistic threats to “kill the Jews” broadcast on Nazi radio in the region were, in fact, the public face of these decisions, which had been secret and previously undisclosed. The Nazis anticipated that they would be able to count on collaboration from the Muslim Brotherhood, but the defeat of Rommel’s forces at el-Alamein by the fall of 1942 prevented the implementation of those plans for mass murder, which revealed that Hitler intended the Final Solution to be a global policy, implemented wherever his armies met with success and working through local allies like Husseini, with whom the Nazi leadership had cultivated intimate political relations based on a shared passion for Jew-hatred.

Nazism, which ended as a major political factor in Europe with defeat in 1945, had enjoyed a robust afterlife in the Muslim Brotherhood and its offshoots.

While working on my 2006 book about Nazi propaganda, I examined several of Husseini’s speeches which had been published by the German scholar Gerhard Höpp. With the works of Küntzel, Mallmann, Cüppers, and Gensicke in mind, I turned to a study of Nazi Germany’s propaganda aimed at the Arab world. I also wondered what American and British diplomatic and military intelligence records might contain in this area.

In fact, the British, and to an even greater extent the United States, knew a great deal more than Washington and London had been willing to make public in the postwar decades. In 1977, the State Department declassified “Axis Broadcast in Arabic,” several thousand pages of verbatim translations into English of Nazi Germany’s Arabic language broadcast from 1939 to 1945, which had been sent every week to the office of the secretary of state in Washington. They were compiled under the direction of U.S. Ambassadors Alexander Kirk and then Pinckney Tuck in the American Embassy in Cairo. The files covering 1941 to 1945 were especially extensive. Though declassified they remained unexamined, or at least were not evident in published scholarship when I found them in the summer of 2007 in the U.S. National Archives at College Park, Maryland.

The “Axis Broadcast in Arabic” translations constitute the most complete documentation in any language of the Nazi regime’s Arabic radio propaganda aimed at North Africa and the Middle East. They include speeches by Husseini and other, unnamed Arabic speakers. The Americans in Cairo documented a veritable flood of vicious antisemitism broadcast on the Nazis’ Middle East radio.

The broadcasts made no distinction between Zionists and Jews. The Jews, according to many broadcasts, were the cause of World War II and enemies of the religion of Islam. Zionism, they claimed, was merely the logical consequence of a supposedly age-old Jewish antagonism toward Islam and Muslims. The Jews and Zionists were imperialists by nature. They controlled the United States, Britain, and the Soviet Union. Nazi Germany was fighting both these Jews and the Jewish-controlled powers of the anti-Hitler coalition. Whereas Nazi propaganda in Germany informed domestic audiences that the regime was in the process of “exterminating” and “annihilating” the Jews of Europe, the propaganda aimed at Arabs urged listeners to take matters into their own hands and “kill the Jews” as fulfillment of both Arab national interests and of the supposed demands of their religion.

The texts of “Axis Broadcast in Arabic” and the files of the German Foreign Office, the SS, and the Propaganda Ministry added necessary texture to the argument that a meeting of hearts and minds—a cultural fusion of Nazism and Islamism—had taken place in Nazi Berlin. The result was a mixture of ideas that neither the Nazis nor the Islamists could have produced on their own: a distinctively Islamist antisemitism that combined a radical antisemitic interpretation of the Koran and Islamic commentaries with the secular conspiracy theories of Nazi Germany.

The Americans in Cairo also reported on the enthusiasm with which al-Banna and the Muslim Brotherhood, and other segments of broadcast and published Arab opinion, greeted Husseini’s return to the Middle East in 1946. For his supporters, his collaboration with the Nazis was a point of pride—at worst an alliance of convenience, but not a source of shame or embarrassment. Though the U.S. State Department was well informed about details of Husseini’s collaboration with the Nazis, as well as the role of ex-Nazi collaborators in the Arab Higher Committee, it chose not to make its files public even in the face of appeals from political liberals such as Sen. Wagner and Congressman Celler and the liberal press in New York. With the publication of Nazi Propaganda for the Arab World, whitewashing or making excuses for Arab collaboration with the Nazis became more difficult. In 2009, the Israeli diplomat and scholar Zvi Elpeleg published Through the Eyes of the Mufti: The Essays of Haj Amin, bringing more textual evidence of Husseini’s hatred of Judaism, the Jews, and of the Zionist project to English readers.

In 2010, the late Robert Wistrich, historian of antisemitism at Hebrew University, published A Lethal Obsession: Antisemitism from Antiquity to the Global Jihad. Wistrich’s massive synthesis argued that first the Nazi collaboration, and then the Soviet-era campaigns of anti-Zionism, had brought about the shift in the global center of gravity of antisemitism from the European heartland to the Muslim majority societies of the Middle East and the Islamic Republic of Iran. In 2011, David Patterson’s A Genealogy of Evil: Anti-Semitism from Nazism to Islamic Jihad synthesized the by-then very considerable English language scholarship on Nazism and Islamism, including discussions of Haj Amin el-Husseini and the Muslim Brotherhood.

In 2014, Harvard University Press published David Motadel’s excellent Islam and Nazi Germany’s War, a work that added yet more archival evidence regarding Nazi and Islamist collaboration. Motadel focused on the collaboration of Husseini and other Arab figures with the Nazi regime, especially in the Balkans and Caucasus. He elaborated further on Gensicke’s work on the Nazi and Islamist collaboration in forming a Muslim SS division in Bosnia, and on Nazi efforts to sympathetically address the cultural and religious customs of Muslim soldiers fighting with the Wehrmacht. Islam and Nazi Germany’s War added still more evidence of the enthusiasm of Nazi leaders, especially Hitler and Himmler, for an understanding of Islam as a religion of warriors, favorable to authoritarian government, implacably hostile to the Jews, and thus a natural ally of National Socialism. Motadel offered important new material on the continuation of the Nazi-Islamist alliance on the European continent, especially on Nazi Germany’s eastern front until the very end of the war in 1945; his book restored this material from its previous role as a footnote in Nazi history to its actual historical role at the center of Nazi ambitions for Muslim lands.

With the benefit of access to previously closed archives, the scholarship of the past three decades has confirmed the arguments of Zionists and liberals in the late 1940s. Haj Amin el-Husseini’s collaboration with the Nazi regime and its anti-Jewish policies was deep and consequential. Though Husseini was not a key decision-maker during the Holocaust, he was an enthusiastic collaborator, shared Nazi hatreds, did what he could to prevent Jewish emigration from Europe to Palestine during the Holocaust, and fanned the flames of Jew-hatred both in Europe and on the radio in the Middle East. Recent scholarship has also confirmed that the ideas which emerged in the fusion of Nazism and Islamism in the Nazi years persisted in elements of Arab and Palestinian nationalism and in the core of the Islamist movements after 1945. The rejection of the two-state solution by Hamas, the Islamic Republic of Iran, al-Qaida, Hezbollah, the PLO, and others remains in part an aftereffect of the fateful fusion of Nazism and Islamism in the 1940s.

One of the key documents of this fusion was the Hamas Covenant of 1988. It has been readily available in English on the internet since soon after 9/11 at the Yale Law School’s Avalon Project website. Reflecting its origins in the Islamist ideology of the Muslim Brotherhood, the covenant based its complete rejection of any Jewish state anywhere in what it calls “Palestine” on its reading of the Koran and commentaries. Armed struggle—that is, war—was essential to destroy the Jewish state. Compromise with it was religious heresy. As was the case in Nazi propaganda aimed at the Middle East during World War II, the Hamas Covenant drew on Nazism’s antisemitic conspiracy theories as it blamed Jews and Zionists for the two world wars. Despite the fact that the Hamas Covenant has long been publicly available, scholars in the United States who regard themselves as leftists have bizarrely sought to present Hamas as perhaps an extreme element of an otherwise progressive global endeavor. Anyone who reads the text can immediately recognize the aftereffects of the Nazi-Islamist ideological fusion that emerged four decades before Hamas published its statement of beliefs.

In 2019, Matthias Küntzel published Nazis und der Nahe Osten: Wie der Islamische Antisemitismus Enstand (Nazis and the Near East: How Islamic Antisemitism Emerged). Currently under consideration for publication in English with the title Aftershock: The Nazis, Islamic Antisemitism, and the Middle East, the work again explores the link between Nazism and Islamism. Part of the “aftershock” was the decision of the Palestinian Arabs and then the Arab League to wage war in 1947 and 1948 rather than accept the U.N. partition resolution. Küntzel rightly places great weight on Husseini’s previously underexamined text, “Islam and the Jews,” first delivered in 1937 at a pan-Arab meeting in Bloudan, Syria. The work was subsequently published in Arabic, and in German in Berlin in 1938. Küntzel makes a compelling case that it was the canonical text of the Islamist war against the Jews, written before Husseini arrived in Berlin, and thus not primarily the result of the Nazi regime. “Islam and the Jews” was his own indigenous creation, and Husseini repeated its themes in his famous speeches in wartime Berlin in which he described Islam as an inherently anti-Jewish religion. He denounced the Zionist project as the modern expression of the Jews’ supposed ancient hatred of Islam.

Husseini’s hatred, which Küntzel calls “Islamic antisemitism,” was the result of the fusion of Husseini’s indigenous, autonomous interpretation of Islam with the modern conspiracy theories of Nazism. Küntzel argues that the decision of the Arab Higher Committee and then of the Arab League to go to war in 1947-48 should be understood as a continuation of a decadelong anti-Jewish war that Husseini and his followers and associates in the Muslim Brotherhood had been waging since 1937—that is, before, during, and after his presence in Nazi Berlin. Küntzel presents the fateful decisions to reject partition and invade the new State of Israel to be direct consequences of the Islamic antisemitism that emerged in the previous decade.

The nonindictment of Husseini and his return to the Middle East was understood at the time by American liberals and leftists to be one of the bitter fruits of an anti-communist consensus that diminished, if not displaced, the passions of wartime anti-fascism and anti-Nazism. Though in the crucial years of 1945 to 1949, the State Department was well aware of the extremism of the Muslim Brotherhood, it declined to bring that evidence to the public or to incorporate it into the public themes of American diplomacy.

The actions of the Soviet Union at first differed sharply from the Western desire to sweep Islamist Nazism under the rug. From May 1947 to May 1949, the Soviet Union and the communist regimes in Poland and Czechoslovakia offered consequential diplomatic and, in the case of Czechoslovakia, military support for the Zionists and then the new State of Israel. They did so at a time when the British government was doing all it could to prevent Jewish emigration to Palestine, and when the United States supported an embargo on arms to the Middle East. The arms that the Jews needed in 1948 came, in violation of the U.N. arms embargo, from communist Czechoslovakia. But when Israeli communists received only 3.5% in the first Israeli elections in 1949, and Ben-Gurion was able to form a coalition government without including the pro-Soviet Mapam party, Stalin realized that the new Jewish state was not going to be a pro-Soviet bastion and reversed course, launching antisemitic purges in Europe, and shifting Soviet foreign policy in favor of the Arabs and against Israel.

From 1949 to 1989, the Soviet Union engaged in a depressingly successful propaganda campaign that suppressed public memory of the brief era of Soviet-bloc support for the Zionist project, the U.N. Partition Plan, and Israel, as well as abundant evidence of the Arab Higher Committee’s Nazi collaborationist era. In place of the actual linkages between leaders of the Palestinian Arabs and the Nazi regime, the Soviet Union and the PLO claimed that the real Nazis and racists in the Middle East were the Jews and the Israelis. This campaign of lies has proven to be among the most successful in world politics.

It was only in the aftermath of the Islamist attacks of 9/11 that historians drew renewed and necessary attention to the role of the Muslim Brotherhood and the ideological fusion of Nazism and Islamism in the 1940s. As Hassan al-Banna hoped in June 1946, Haj Amin el-Husseini and the Arab Higher Committee did indeed “continue the struggle” waged by Hitler against Judaism, Jews, and the Zionist project. Whether the scholarship about these issues receives the attention it deserves, and whether it has any impact on changing political attitudes toward Israel and its adversaries, remains to be seen. But it is getting harder to ignore.

Jeffrey Herf is professor of modern European history at the University of Maryland, College Park. His most recent publication is Israel’s Moment: International Support for and Opposition to Establishing the Jewish State, 1945-1949 (Cambridge University Press, 2022).