The Modesty of Ruth

There is a right time, and a wrong time, for naked legs

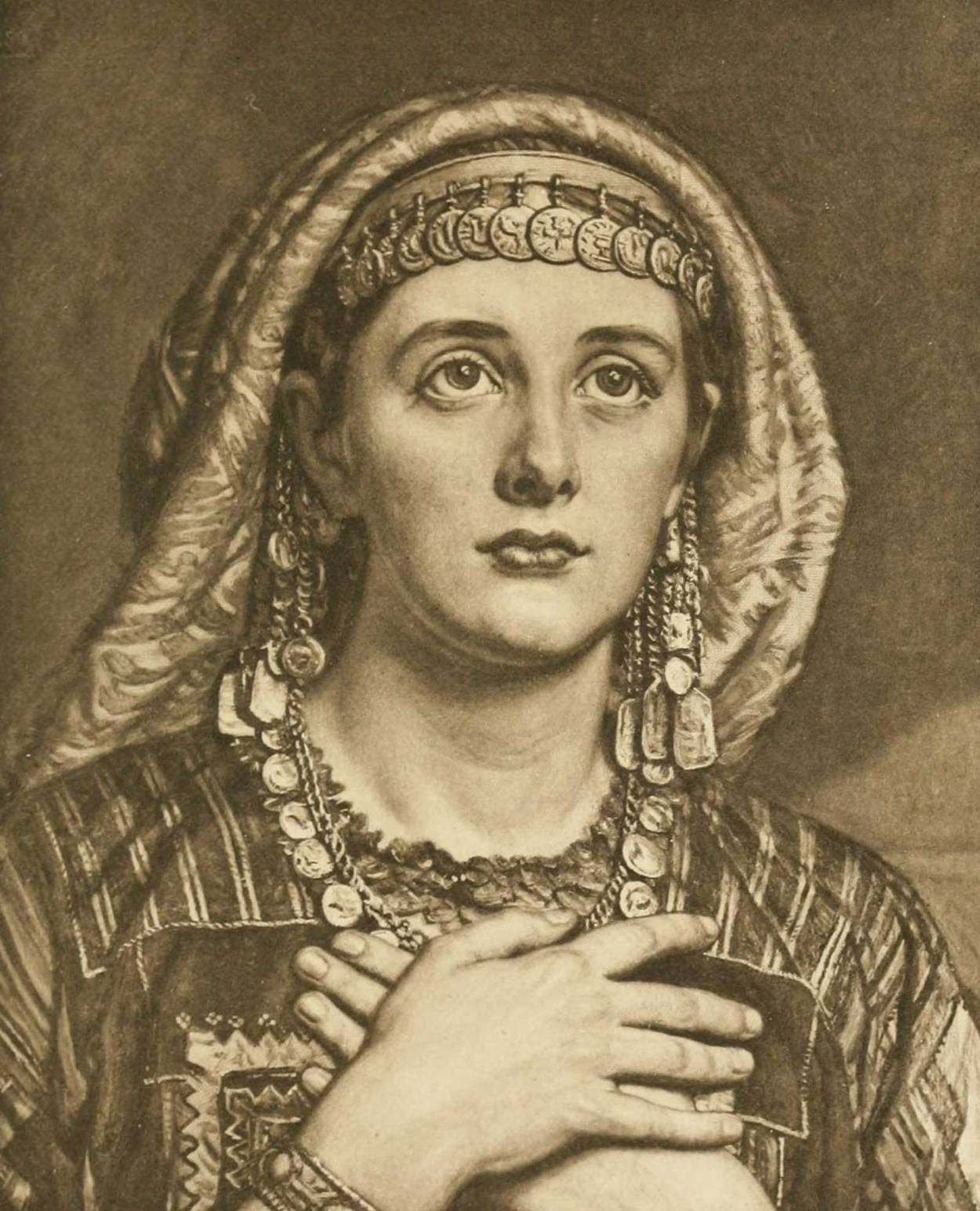

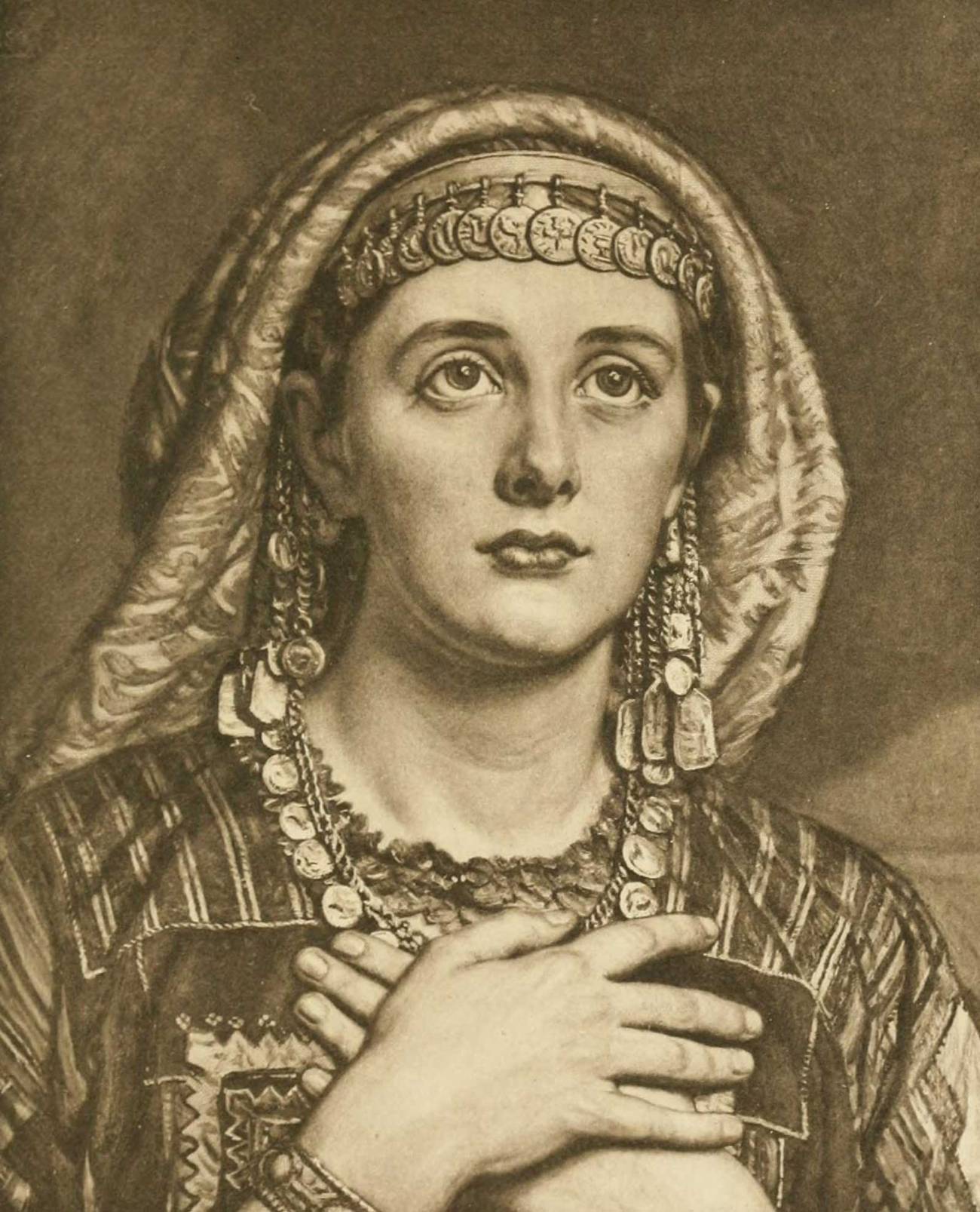

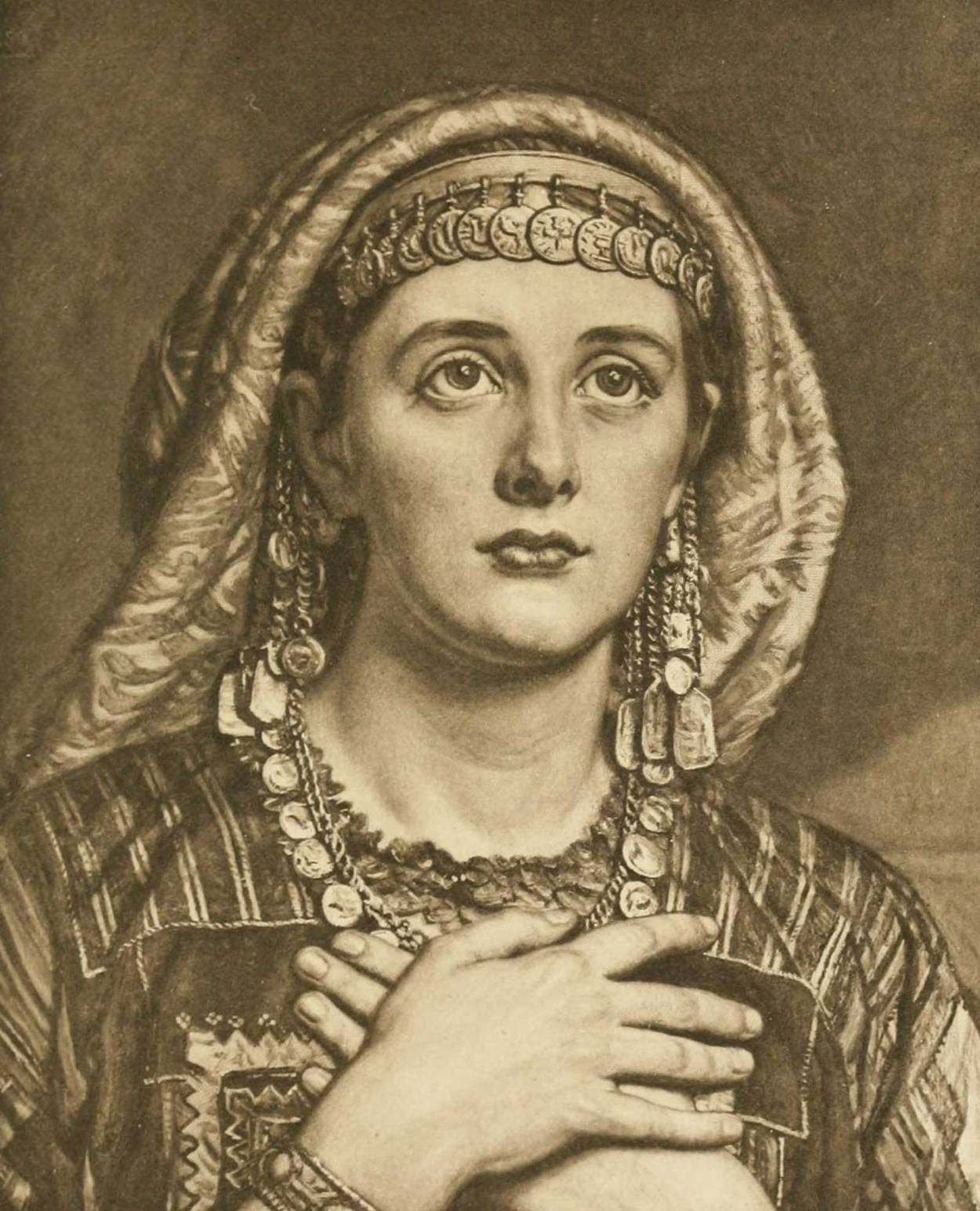

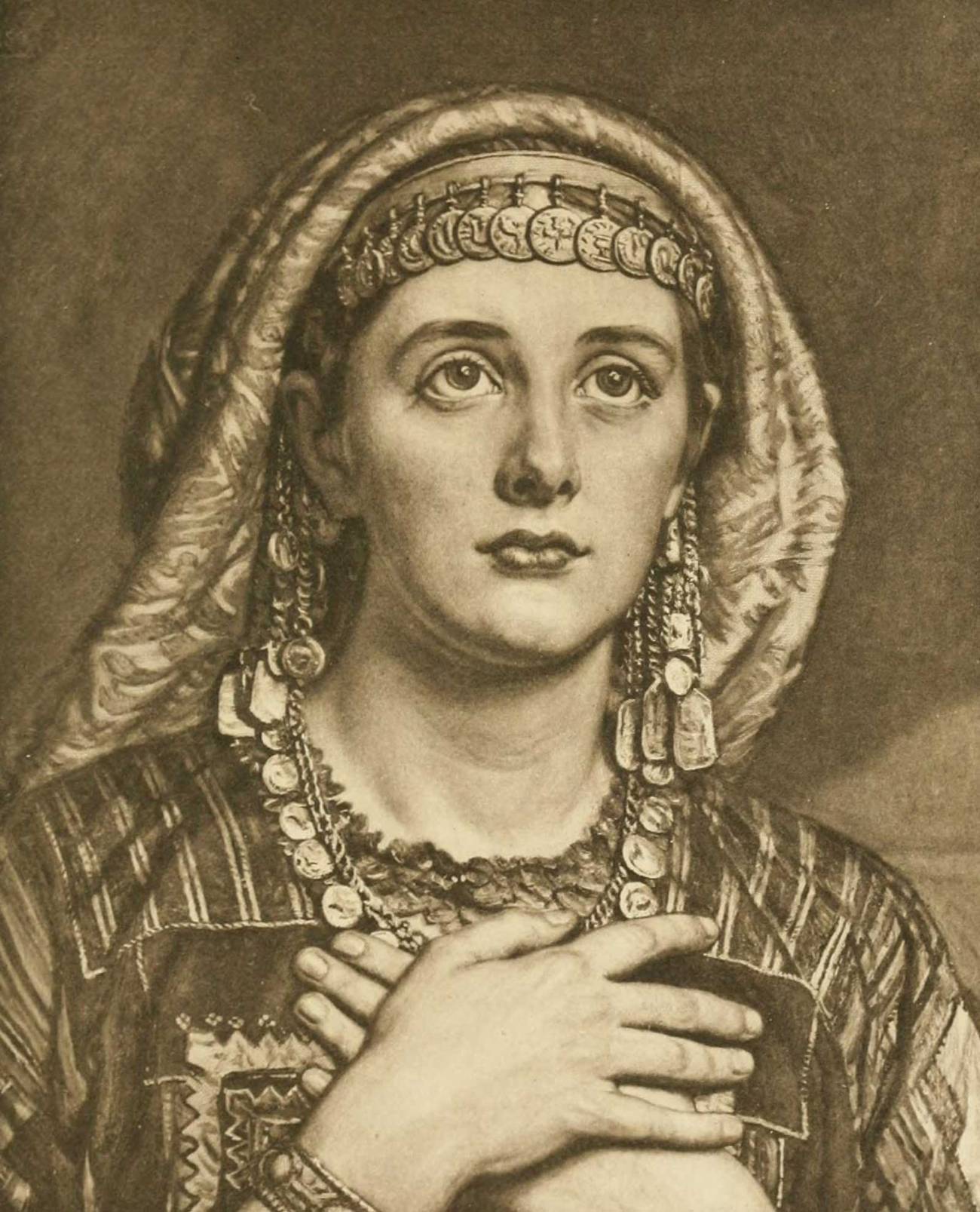

I think about Ruth every time I drop a notebook. The protagonist of her own biblical book, this woman knew how to retrieve things from the floor. It’s one of the first things I learned about her, as a third grader in an Orthodox Jewish day school: The other women in ancient Israel, the midrash tells us, would bend over at the waist when gathering in the fields to harvest the remnant grain, their dresses indecently riding up their legs. But Ruth would kneel at the knee. (She also let everyone else have their fill before collecting what she needed, and she didn’t laugh with the male farmhands as the other women did.) In crouching down this way, she preserved her modesty. This, we were told, is how a true daughter of Israel picks things up off the floor. This, we were told, is why Ruth was noticed by Boaz, the eligible bachelor and wealthy owner of the field who was also her distant relative and would go on to marry her.

The teaching has its sources: In Ruth 2:5, Boaz asks the head of his workers about the new woman, and he is told that she is a Moabite named Ruth who has come back to Israel fleeing famine, with her mother-in-law, Naomi. There is already the hint of interest in Boaz’s question, just three Hebrew words: L’mi ha’naarah hazeh? To whom does this woman belong? As it turns out, she belongs to only Naomi. Her husband is dead. But Boaz and his question mildly scandalized later Jewish commentators. Rashi, writing in the 11th century, comments, “And was it the way of Boaz to ask about women?” (Subtext: Surely not! What kind of a man asks about women?!) Rather, Rashi quickly explains, Boaz asked only because he noticed her modest habits, the way she kept her skirt lowered while the other women hiked theirs up, that she would only take two sheaves of grain when three were available, that she would pick the fallen sheaves from a sitting position instead of a standing position so “as to not bend over.” Subtext: The modest woman does not take too much, she bears the discomfort of a clinging skirt, she is mindful, always, of who is watching. There is a right way and a wrong way to gather a notebook from the floor.

There are many reasons we read the story of Ruth on Shavuot. The most obvious is that Ruth is the hero of the harvest story, and Shavuot the holiday of the harvest. But the personality of Ruth, the gentle passive femininity of her doe-eyed modesty that’s passed down through the telling of the story, always felt antithetical to me, to the story of Mount Sinai. Shavuot is not just the harvest holiday, but the celebration of the mysterious, momentous moment that happens at Mount Sinai: the moment God takes Israel as a bride, offering the Torah as a betrothal ring, the mountain held over our heads like a chuppah, or maybe like a threat. A moment of such stillness, not even a bird flapped its wings. And then we accept, and the slaves of Egypt become the Jewish people. We celebrate. We stay up all night, because what bride is expected to sleep the night of her wedding?

How unlike Ruth, the whole thing. The people of Israel are no quiet lover, hopeful in the field. They are brash, angry, full of demands and wants. They are not grateful for their gifts of parched grain. They are stiff-necked, complaining, loud. They are scornful of God on almost every page. The union, in some accounts, was practically forced.

What of them and Ruth, this woman scrubbed of needs? This woman, poor and hungry in a strange land who demurely declines her full measure of grain. The Ruth I was given has no complaints. She is modest. This modesty frees her from the suspicion of want that her circumstances suggest. The other women, we are told, take as much as they can as quickly as they can. The desperation of the other women is sad. Ruth is not sad. She is modest. Subtext: There is something immodest about a desperate woman. Dangerous.

Only later did I question the modesty of Ruth, the woman I think of whenever I drop something I need. This is a woman who, after all, in just a few verses will go down to the threshing floor at night in her finest clothes and slip into the bed of Boaz while he sleeps. She will “uncover his feet and lay down” just as her mother-in-law instructs her. In the Bible, Boaz will awake in the middle of the night, startled to find a woman at his feet. He says, very simply, into the night: Mi at? Who are you? Ruth gives him her name before asking directly, “Spread your robe over your servant, for you are a redeemer.” Boaz, the distant relative of her now-dead husband, is the man to whom the responsibility of marriage has fallen. He is a go’el, a redeemer, of Ruth. The law is clear. To whom does this woman belong? As it turns out, she belongs to him.

We remember the value of being demure and discreet, and we remember all that is possible when we are immodest about what we want, about our love.

Boaz is full of happiness at her request. Ruth has not gone after some younger man, but after him, and he calls this a great kindness. His delight, in this moment, has always surprised me. She is a Moabite stranger, late arriving to a new place, in acute need of a husband to ensure her ability to eat, and he is a wealthy man who owns many fields and has shown her kindness. Of course she chose him. There are no other men at her door, that we know of. But I like how his happiness balances the score, a little, between them. Suggests the possibility of choice. She is not desperate. She is choosing Boaz, and he is delighted. Some complications ensue. There is another redeemer who must be dealt with, there is the matter of the field, there is the matter of getting Ruth home safely in the morning before anybody realizes that a woman has been on the threshing floor. But in the end, Ruth and Boaz end up together and have a child, and through that child the Messiah will one day come, and until then, the daughters of Israel will bend at the knees and not the waist, and men will come to marry them.

But that is not the only story. The modest Ruth attracts the eye of Boaz, but it is the brazen Ruth who prompts the marriage. I had never noticed that. The contrast between her covered legs in the field and his uncovered feet at night. The way the brashness is rewarded. Here is Ruth, modest, beautiful Ruth, lying at the feet of Boaz, asking him to redeem her. Here is Boaz, full of joy. And here is the Israeli people, asking for more water, cursing the God that redeemed them from Egypt, from gleaning in someone else’s field. A triangle of ancestors. What do we make of this trio, the night before Shavuot? Is it better to grab everything one can carry from the field or to live by the restraint of the marriage bed? The people of Israel seem unsure. The mountain is held over our heads. For a still, silent moment, we look at the list of modesty norms presented to us, alongside the promise of protection. And then the people of Israel, full of doubt, agree. A flash of joy. A union. A fate set in motion, as evolving as the seed destined for bread, destined for redemption. There is a right time, and a wrong time, for naked legs. A modest woman knows the difference. A modest woman knows how to retrieve what she wants from the threshing floor. The Ruth I remember when I bend down at the knee is also the Ruth who uncovers the legs of Boaz, a woman unworthy of being forgotten. A people worthy of God’s love. A love story either way. We remember the value of being demure and discreet, and we remember all that is possible when we are immodest about what we want, about our love. To whom does this people belong? To a God delighted.

Shira Telushkin is a writer living in Brooklyn, where she focuses on religion, beauty, and culture. She is currently writing a book on monastic intrigue in modern America.