Was Slavery in Egypt So Bad?

It’s tempting to draw parallels to American slavery, but the Bible paints a very different picture

Can you imagine a European rabbinic court telling the Jews in June 1945, one month after the Germans were defeated and with the Holocaust just barely ended, something like, “Do not hate the Germans, for you were sojourners in their land for many hundreds of years?”

It’s unthinkable, right? Now, backtrack to biblical times: Read the story of the exodus, and you’ll see that the Israelites had barely left Egypt when the Torah instructs, in Deuteronomy 23:8, “You shall not abhor an Egyptian for you were a sojourner in his land.”

Notice, the word “slave” or “slavery” is starkly absent here; accented only is the Israelites’ residing in the land of the Egyptians.

One would think that, considering their long bondage, the Israelites would hold Egypt and the Egyptians in contempt and never set foot in their land again, which is the attitude some Jews today still have toward Germany, including many who had never experienced the Holocaust. Even more astonishing is the Torah’s lax attitude regarding socializing with the Egyptians: Given their experience, it would have been natural to tell the former slaves not to associate with the nation, and the people, that had kept the Israelites in servitude for several centuries. But in the very next verse, Deuteronomy states that “children born unto them [the Egyptians] may be admitted into the congregation of the Lord in three generations,” a rather liberal attitude toward the enslavers. Contrast this to how more stringent is the Torah to the Ammonites and Moabites (Deuteronomy 23:4-5), who may not “be admitted into the congregation of the Lord, none of their descendants, even unto the tenth generation, for they did not meet you with food and water on your journey after you left Egypt …”

An odd stance, indeed. For the one time the Ammonites did not welcome the Israelites leaving Egypt, their descendants cannot come into the Israelite congregation. Yet the Egyptians, who had enslaved the Israelites for 430 years, are granted special exemption. Why?

In Exploring Exodus, the noted Bible scholar Nahum Sarna posits that the Israelite bondage was more like a day slavery, where men left their homes for work during the day and returned in the evening. “There is no evidence,” he wrote, “that the Israelite women were enslaved or that slavery involved the dissolution of the family unit.” Sarna then cites the famous verse in Exodus 3:22, where the women “borrowed” jewelry from their neighbors and the “lodger in her house” as proof that the “Hebrew slaves” and the Egyptians actually lived side by side. The fact that an Israelite woman actually had an Egyptian woman residing in her home, perhaps even paying rent, gives another surprising twist to the economic side of avdut, or servitude.

This proximity of Israelites and Egyptians is further accented in Exodus 11:2, with God saying: “Tell the people that each man shall borrow from his neighbors, and each woman from hers, objects of silver and gold.” Whereas earlier in the story only women were mentioned, here men are also introduced. This borrowing is repeated for the third time in Exodus 12:35-36: “The Israelites had done Moses’ bidding and borrowed from the Egyptians objects of silver and gold, and clothing. And the Lord had disposed the Egyptians favorably toward the people, and they let them have their request; thus, they stripped [in Hebrew: va-yenatzlu] the Egyptians.” (Other translations of va-yenatzlu include “stripped bare,” “exploited,” and “took advantage of.”)

Added to the Israelites’ rather unique bondage are their possessions: property and plenty of sheep and cattle. When Moses demands of Pharaoh that the Israelites leave, he states, “we will all go, young and old … sons and daughters, our flocks and herds …” In other words, the people will depart Egypt with all their wealth—for at that time, in that part of the world, sheep and cattle were considered wealth.

The Israelites’ wealth must have been impressive, for a cunning Pharaoh, suspecting that they might depart altogether and not just go out into the wilderness to worship, tells Moses that the people can go, even the children, “Only your flocks and your herds shall be left behind.” To maintain flocks of sheep and herds of cattle, grazing land is needed and caretakers for the animals. The women might have been shepherdesses, as was Rachel; or, quite likely, with the burden of family, the men, along with youngsters, also took care of their flocks and herds upon returning home from work.

And so, despite the burdens of bondage, the Israelites did not lack food; they had meat and dairy products from cows, sheep and goats. Later, in Numbers 11:5, we get a small catalog of the nonmeat foods that rounded out the Israelites’ diet. When they complain about the vitamin-pill like manna, we hear them longing for the real foods they used to have: “… the fish we used to eat free in Egypt, the cucumbers, the melons, the leek, the onions and the garlic.” Quite a well-balanced diet for slaves, unlike the 18th- and 19th-century Black slaves in the United States, who were poorly fed.

Nowhere does the Torah state that the Israelites were the property of the Egyptians; nor do we read of any Israelite slave being sold. In the United States, the Black slaves were the property of the owners and could be sold, bought, and traded. Unlike the Israelite slaves with their flocks and herds, the slaves in America were not allowed to own property.

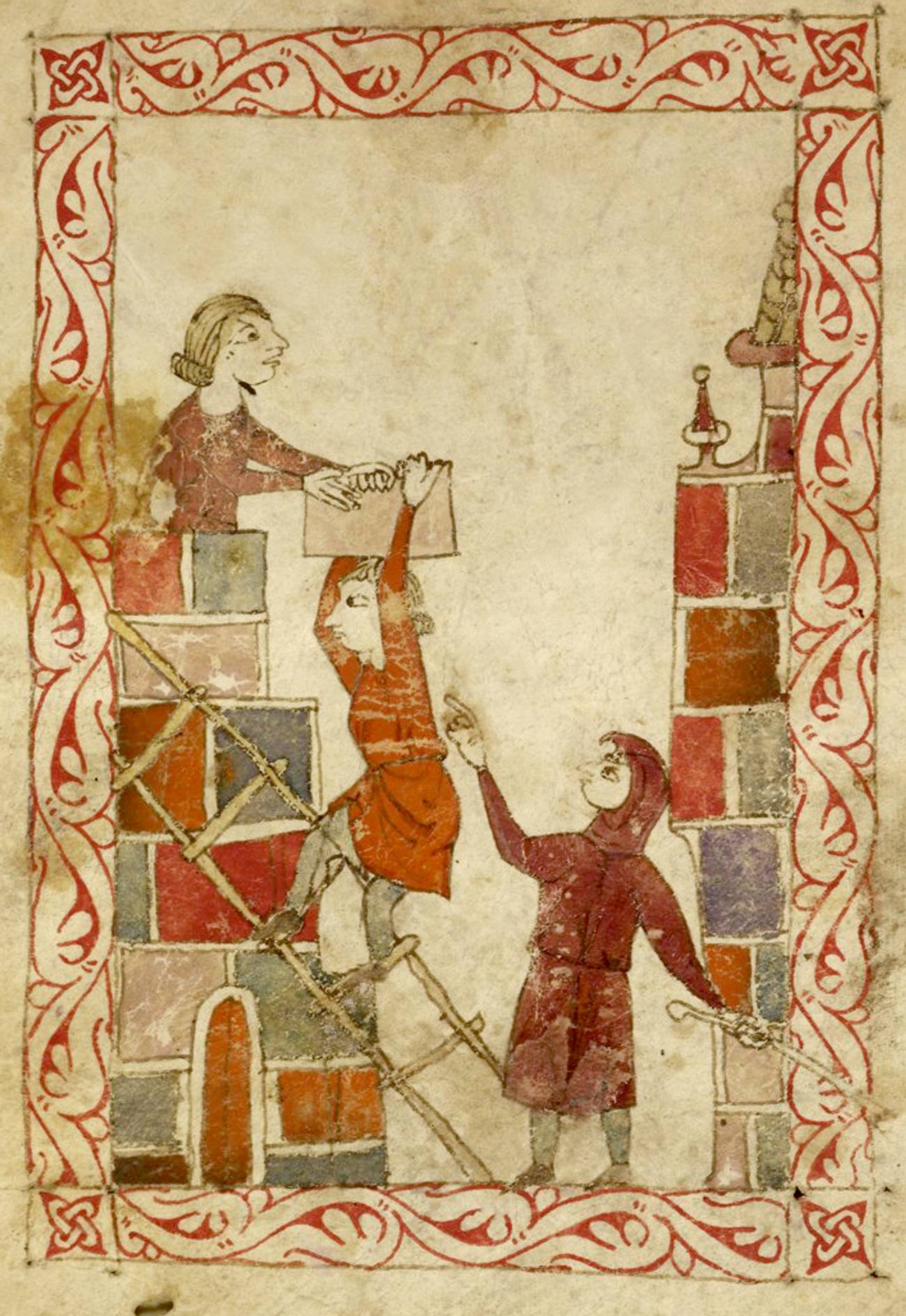

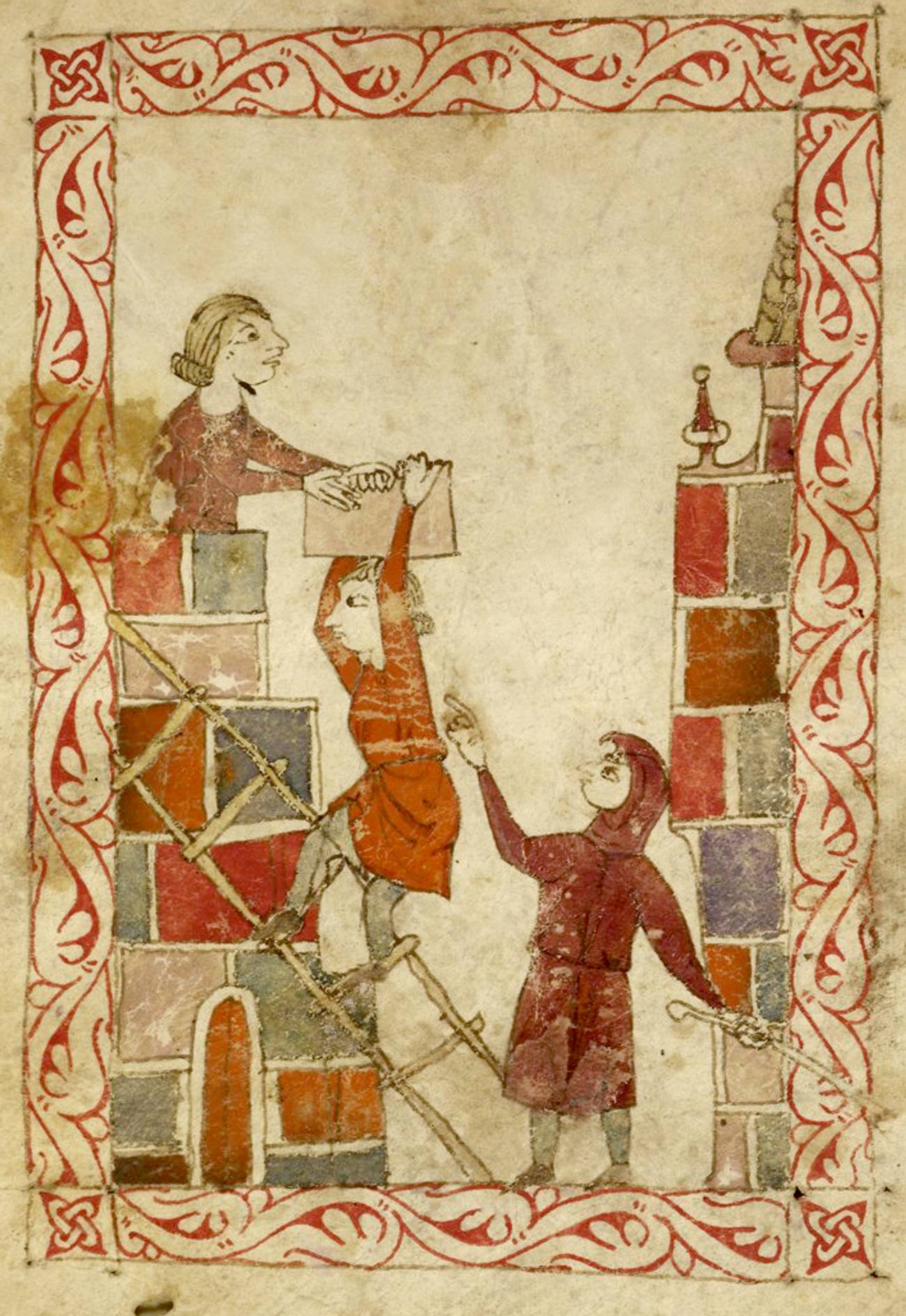

What, then, do we know about the precise nature of the Israelites’ bondage? “So they set taskmasters over them to oppress them with forced labor,” Exodus 1:11 tells us, and verse 13 adds that “The Egyptians imposed tasks upon the Israelites ruthlessly; they embittered their lives with harsh labor at mortar and brick and in all sorts of work in the fields, with all the tasks that they ruthlessly imposed upon them.” The only definitive citations of cruelty we’re given are the Egyptian taskmasters beating the Israelite foremen, and that an Egyptian beating a Hebrew prompts Moses to kill the Egyptian and rise to become the Israelite leader. The word “slave” is not mentioned in this specific verse; Exodus 2:23 does state that the Hebrews were “groaning under the bondage and cried out,” but there are no specific depictions of this mistreatment. And in Exodus 3:7-9, when God calls Moses and sends him to Pharaoh, He mentions “the plight of My people, the suffering, the taskmasters, the cry of the Israelites, the oppression …” But here, too, no instances of oppression are offered.

Yet, with all the hard labor, once the Israelites are liberated from bondage and have departed Egypt and have grown thirsty in Rephidim, they “grumbled against Moses and said, ‘Why did you bring us up from Egypt, to kill us and our children and livestock with thirst?’” And further, after hearing the negative report of the scouts who have returned from touring the Land of Canaan, the land promised to the People of Israel, the Israelites clamor to return to Egypt (Numbers 14:1-4), with the telling words, “If only we had died in Egypt … It would be better for us to go back to Egypt … Let us appoint a chief and return to Egypt.” And when Korah and his followers complain to Moses (Numbers, Chapter 16), Dathan and Abiram declare: “Is it not enough that you brought us from a land flowing with milk and honey to have us die here in the wilderness, that you should also lord it over us?” In their complaint, the Hebrews ironically use for Egypt the very phrase, “land flowing with milk and honey,” that is synonymous with the promised Land of Israel.

Presumably, after themselves enduring bondage, the enslavement of others, and especially of fellow Hebrews, should have been anathema to the People of Israel. Nevertheless, like other nations in the Middle East, they did own slaves. In fact, many Torah laws deal with this. For instance, in Deuteronomy 15:12-17, if a man is eligible for release after six years of bondage and wants to stay with his master, his ear is pierced with an awl—to show everyone that he is a slave and is indentured to his master in perpetuity. If during his servitude he changes his mind and leaves, the branding no doubt marks him as an escaped slave. Over the centuries, Jews continued to own slaves, even up to and during the Talmudic period, from about 200 CE to 500 CE. Ironically, on the Passover Festival of Freedom, when Jews celebrate their liberation from slavery, we read about the famed Rabban Gamaliel ordering his slave, Tebi, to “Go roast the Passover-offering for us on the grill.”

None of these observations is meant to lessen the significance of Passover or the story of the exodus. But if we somewhat loosen our attitude to the bonds of bondage, a more nuanced understanding of our history might emerge, one that gives us a more intricate understanding of our forefathers’ anxieties, hopes and motivations, and, perhaps, ours as well.

Curt Leviant has translated four volumes of Chaim Grade’s fiction, including his two-volume The Yeshiva. He is also the author of 14 novels, the most recent of which are the just-published Tinocchia, the Adventures of a Jewish Puppetta and The Woman Who Looked Like Sophia L.