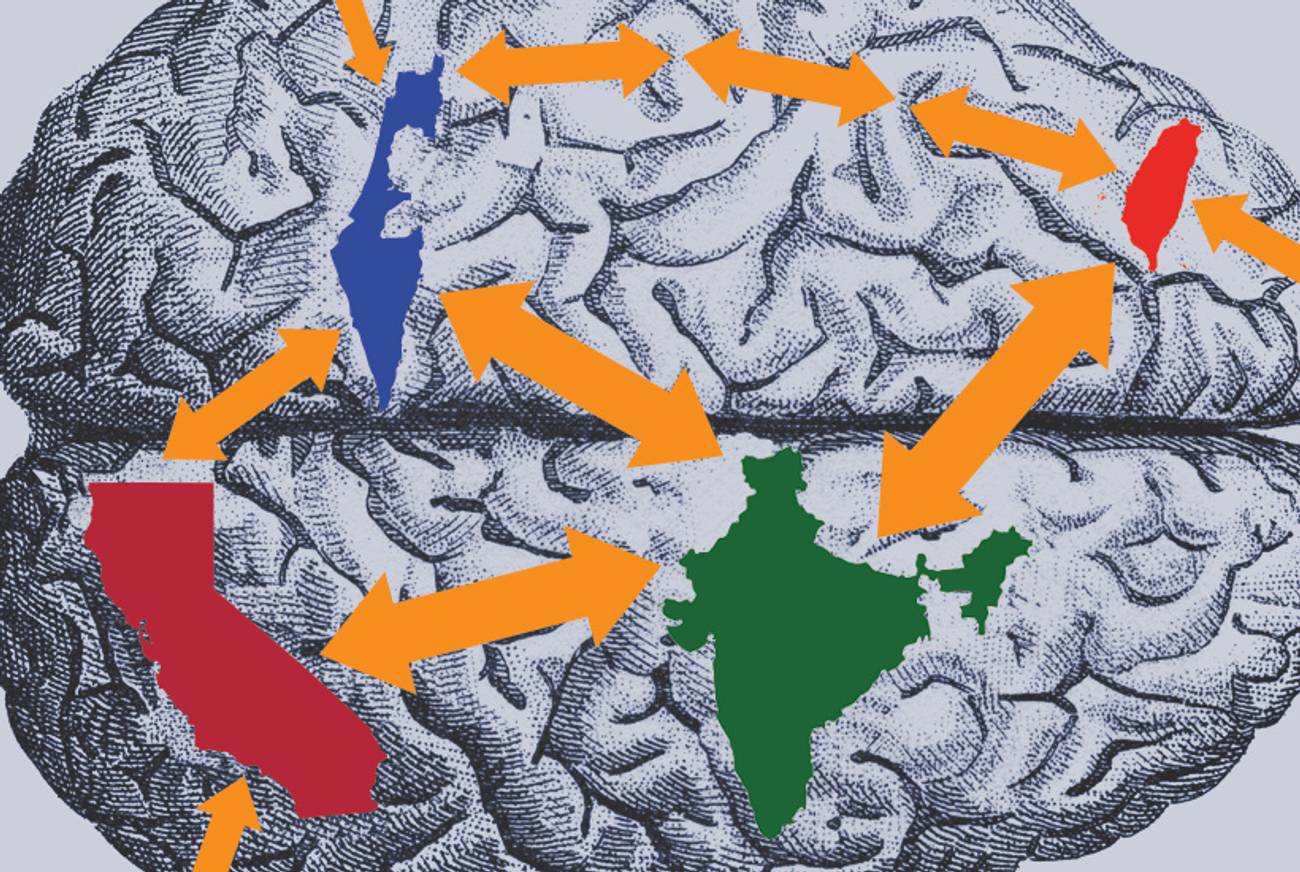

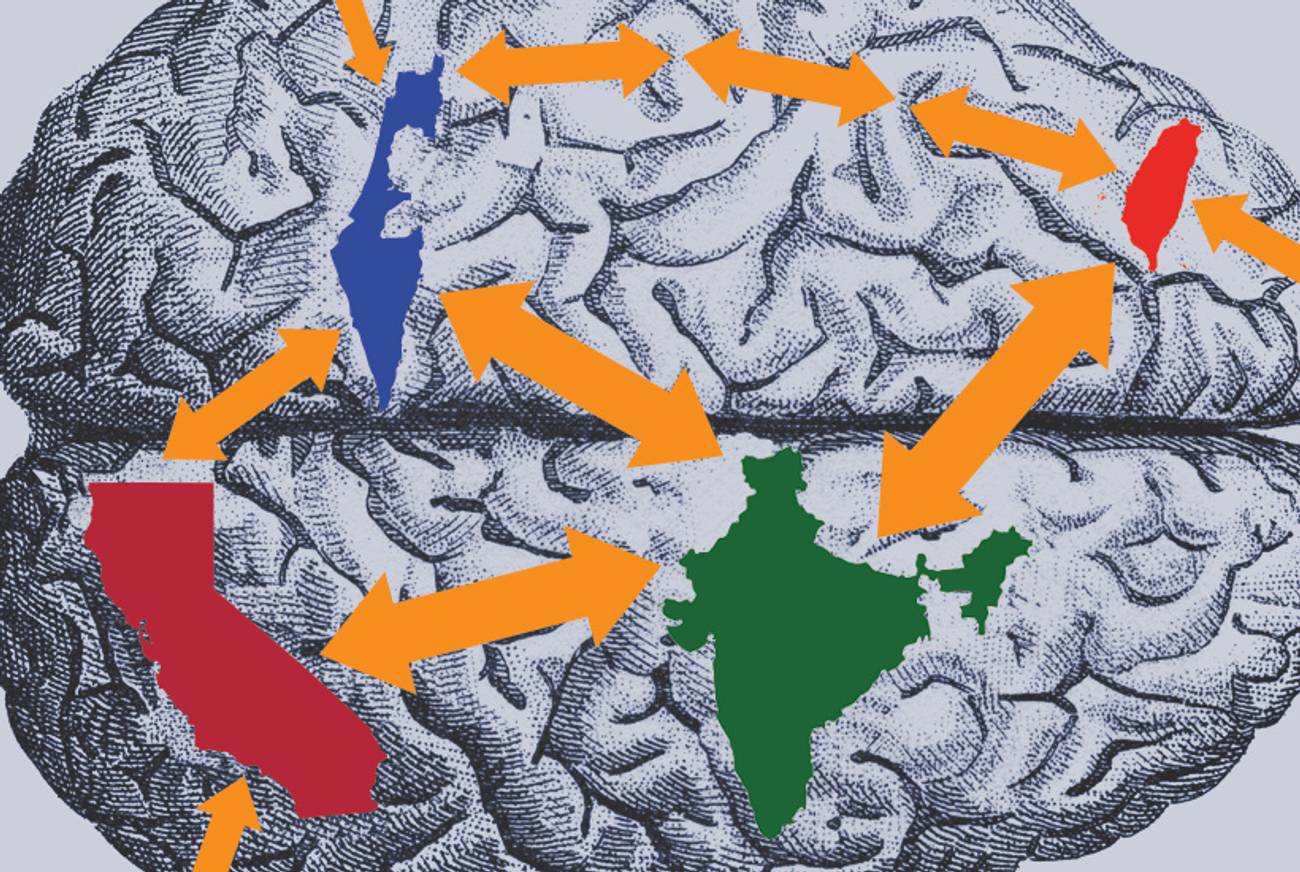

Forget Brain Drain. The Truth Is Israel Gains When Talent Goes Abroad.

The much-deplored ‘escape of the brains’ has actually brought closer ties with Silicon Valley, India, and even Taiwan

Last week I received yet another email from Israel’s National Brain Gain Program, the government initiative devoted to reversing what has been coined in Hebrew brichat hamochot—literally, the escape of the brains. Both the concern over the departure of highly educated and skilled nationals to other countries and the initiatives to encourage their return are not unique to Israel. The latest panic over the bricha seems to have reached new heights, triggered in part by a new report from the Taub Center for Social Policy Studies showing that the emigration rate of Israeli academics is among the highest of Western countries and that Israelis are disproportionately represented in academic institutions abroad.

The figures are striking: The number of Israeli physicists on top-40 American faculties is a 10th of the entire corps of physicists in Israeli research universities, and top Israeli chemists in America represent an eighth of the entire discipline in Israel. In philosophy that percentage nearly doubles. But the most alarming statistics lie in economics and computer science, where the number of Israelis teaching in the United States is roughly a third of those who remained at Israeli universities in each discipline. “Some of the leading U.S. departments have no less than 5-6 Israelis each,” the report said. These figures appear to be far higher than in any OECD country’s parallel migration of researcher to the United States and prompted Finance Minister Yair Lapid to speak out against those “who are prepared to throw away the only homeland the Jews possess simply because life is more comfortable in Berlin.”

But how concerned should countries like Israel—nations that invest heavily in education only to see graduates move abroad—actually be? Not very, it turns out. In a report I recently co-authored for the United Nations Industrial Development Organization, one central insight emerged: For these nations to thrive, they must encourage and facilitate their international knowledge networking capacities. Economic geographers call this concept “brain circulation”—the flip side of the dreaded brain drain. A country’s connectedness, it turns out, directly influences its economic development in a multitude of ways. One example is that skilled emigration is significantly and positively correlated with foreign investment in the country of departure.

On a global scale, the human capital pool has become key to understanding the challenges of development. An enduring puzzle for development economics has been why similarly situated countries diverge so significantly in their rates of growth—but economists now understand that far beyond the mere raw access to capital and labor, the availability of local knowledge and human capital are crucial for a nation’s success, and regions that both encourage open circulation of talent, and compete most fiercely to keep talent, win the most.

In the Israeli government’s own brain-drain figures, there is a certain battle of numbers in play. The national statistics bureau counts as migrants any Israeli living abroad for over a year. But so many of those living abroad stay for just several years, and, when looking at the actual evidence per year, the numbers of returning Israelis is not all that much lower than the number of those moving abroad. Nevertheless, in 2012, Israel ranked 30th on the list, a drop from its rank of 23 a year earlier that stemmed more from an increase in connectedness for other countries than from a change in Israel’s ties—a sign that policymakers around the world are putting in deliberate effort to increase the knowledge networks and ties through collaborative research efforts and information exchanges.

***

Many entrepreneurs, much like academics, boomerang frequently. They spend some years abroad, return, and then repeat. Most notable among these brain circulations, both in academia and high-tech industries, are the back-and-forth travel between the United States, Japan, China, Israel, and India. It was these inter-regional hoppers that brought the model of high-risk venture capital investment in early stage start-ups to Israel in the early 1980s. The founders of Check Point, Israel’s premier network security company, followed this pattern of circulation, and, more recently, so did the founders of Waze—the traffic app that was acquired by Google this year in the biggest deal yet for an Israeli technology company.

Indeed, Waze is a good example of the importance of transnational human capital. We know that in regions with dense professional networks and rich human capital, like California’s Silicon Valley or Israel’s so-called Silicon Wadi, each inventor becomes more inventive, which has enabled technology and biotech industries to grow exponentially fast—and it is specifically the cross-fertilization of creative people that drives the phenomenon. Even in the age of Skype and Dropbox, a great deal of knowledge transfer continues to rely on direct human communication. Many of the most important innovations and scientific breakthroughs are frequently difficult to transmit by sitting on a conference call—or simply by reading a patent application document or a scientific journal. Important knowledge remains tacit rather than codified.

Waze operated in a Silicon Valley office, which included the company’s co-founder and president Uri Levine, long before the Google offer. Perhaps not unrelated, though separated from the actual Waze deal, Google chairman Eric Schmidt’s private investment fund, Innovation Endeavors, is managed by Dror Berman, an Israeli who came to Stanford after his military service at the IDF. Rather than looking at these talent flows as a net loss to Israel, taking a brain circulation perspective often points to an overall gain. The real analysis of “brain drain” should take into account not only the costs of skilled nationals living abroad but also the benefits of diaspora networks.

While the benefits of circulation accrue to countries, they also—perhaps most crucially—accrue to the circulators themselves. A recent OECD study suggests that the productivity and impact of researchers who circulate between countries are significantly greater than those who have stayed put during their career. And beyond their individual enrichment, Israeli academics teaching at American research institutes help create joint programs, such as the new the U.S.-Israel Center established last year at the University of California, San Diego, which is designed to support collaborations between Israelis and Americans in both business and academia, including for example in the area of social entrepreneurship.

Israelis aren’t the only ones playing in this field. Silicon Valley’s Taiwanese and Indian engineering communities also show how this connectivity operates on the ground. These migrant engineers have built a two-way bridge between Taiwan’s and India’s tech communities and California’s. They serve as key intermediaries and have a great edge over American-born competitors, because of their contacts, relations, cultural insight and language fluency. The result is a global network between the sending and receiving country that enhances opportunities for both countries. Immigrants are twice as likely to be entrepreneurs, and transnational entrepreneurship is on the rise. The circulating entrepreneurs with dual ties seek merger and acquisition opportunities back home, and they facilitate joint ventures across borders. If in the past Silicon Valley companies sought out opportunities for cheap production and low-level application in India, Taiwan, and Israel, co-development and investment are the contemporary reality. In academia, a similar enrichment is generated by brain circulation.

And the bridges get built in all directions. We have in the past decade seen an increase in partnerships between high-circulation countries. Taiwan has a growing domestic venture-capital industry, with $1.3 billion in annual investments—but Taiwanese investors have been putting their money into Israeli start-ups. Meanwhile, Israel and India are exploring a free-trade agreement, which would bolster the already-robust $5 billion bilateral trade between the two nations by enabling freer movement of engineers, scientists, and students between the two countries.

So, rather than encouraging hand-wringing about the brain drain, Israel would be wise to focus on nourishing connectivity, encouraging boomeranging, and engaging in the international talent wars—both to bring its own home, and to become a destination for the brightest from other nations. In recent years, Israeli labor courts have made strides toward adopting changes to employment law modeled on California’s, which voids restrictive noncompete agreements. The results have been striking. Over time, California has experienced a brain gain, drawing the best talent from other states, and it has gained twice: first by creating a more open and supportive entrepreneurial environment than its counterparts such as Boston and Ann Arbor, and then by sustaining those vibrant networks.

A study of India’s booming high-tech labor market describing the rise of “a global war for talent” offers potentially illuminating lessons. The study concludes that in retaining their employees, the best industry leaders have realized that employees care greatly about nontangible rewards such as pride, satisfaction, fair treatment, and professional support. Ambitious individuals with great career aspirations readily forgo some monetary compensation to be where their talents and contributions are appreciated. The newly established Centers of Research Excellence—known as I-COREs—which the Israeli government is establishing at its public universities are exemplary of the right kinds of efforts to strengthen long-term commitments to Israel’s academic vision and stature. National human capital policies shouldn’t be simply about “brain-drain reversal” but must be about the new investment in human capital, retention, and network formation.

***

You can help support Tablet’s unique brand of Jewish journalism. Click here to donate today.

Orly Lobel is the Don Weckstein Professor of Law at the University of San Diego and founding faculty member of the university’s Center for Intellectual Property and Markets. She is a frequent visiting professor at Tel Aviv University. Her latest book is Talent Wants to Be Free: Why We Should Learn to Love Leaks, Raids, and Free-Riding.

Orly Lobel is the Don Weckstein Professor of Law at the University of San Diego and founding faculty member of the university’s Center for Intellectual Property and Markets. She is a frequent visiting professor at Tel Aviv University. Her latest book is Talent Wants to Be Free: Why We Should Learn to Love Leaks, Raids, and Free-Riding.