The Failed British Double-Cross of Israel

Heretofore overlooked British General Staff documents demonstrate that the oft-marginalized Lehi leader Avraham ‘Yair’ Stern’s assessment of British intentions toward Mandate Palestine was correct

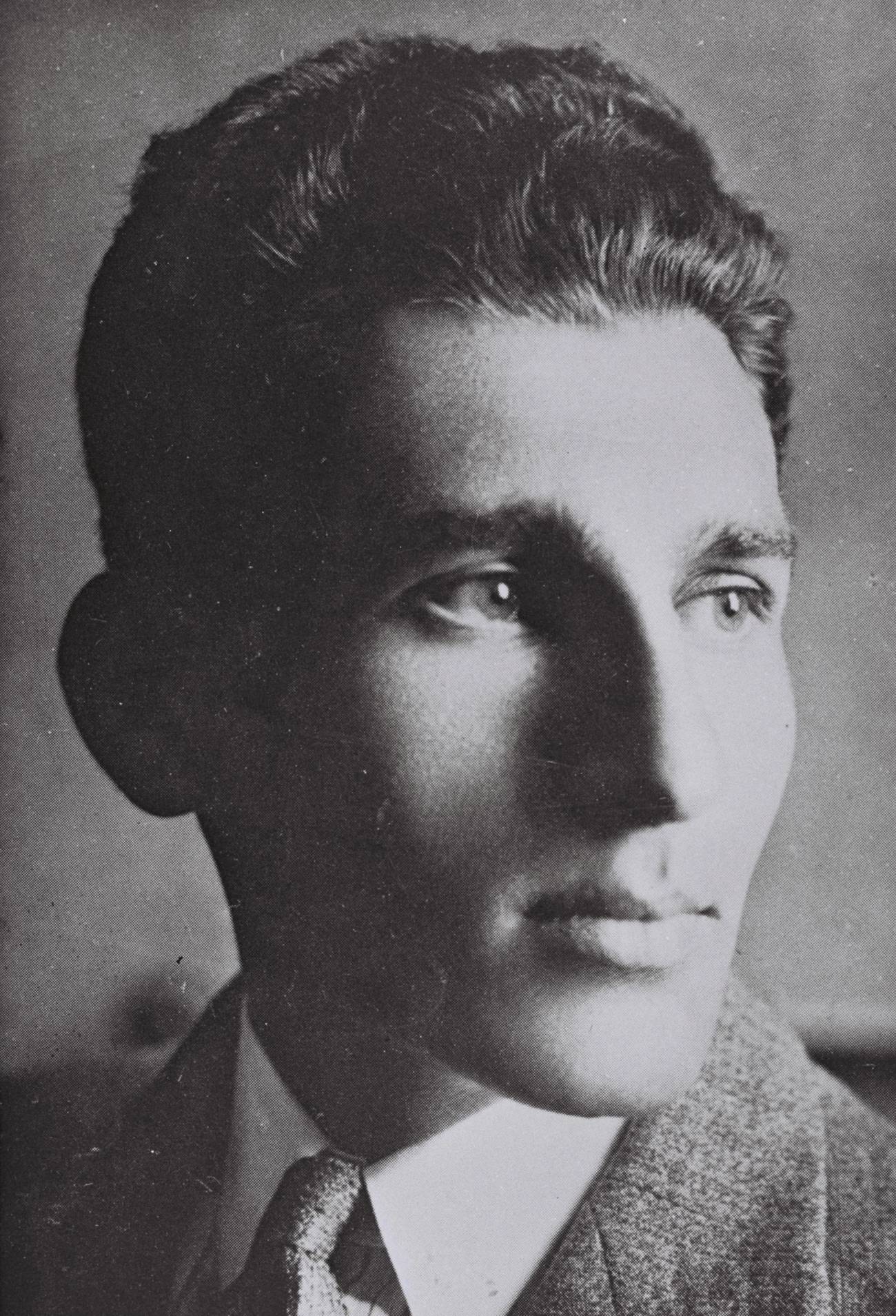

When the warrior poet Avraham “Yair” Stern founder and leader of Lohamei Herut Israel (Lehi, “Fighters for the Freedom of Israel”) who believed that the British had to be forced out with assassinations and bombs and would never leave voluntarily, was killed after being captured and handcuffed by British detectives on Feb. 12, 1942, no Jew could celebrate his death.

But the leaders of the Jews of British Mandatory Palestine, already then led by David Ben-Gurion, viewed Stern’s death as a gain for the national cause rather than a loss—and not only because the poet and his followers were reckless political dilettantes: Some fantasized alliances with Mussolini, even the Nazis, as well as Arab nationalists in a common anti-British cause.

At a time of maximum danger—Rommel seemed to be on the verge of conquering Egypt, with Palestine next—Ben-Gurion and his allies doggedly pursued cooperation with the British in spite of bitter disappointments. Perhaps the worst of these was the May 1939 White Paper which limited the immigration of Jews to 75,000 over five years, sentencing countless European Jews to death at the hands of the Nazis. Yet Ben-Gurion believed, and rightly so, that the British were the least-bad allies the Jews could have.

Nor did Ben-Gurion have much choice. The Americans had refused to enter the war even after the Germans had conquered most of Europe. They still refused to act when the Germans seemed on the verge of defeating Russia, which would soon mean Britain’s defeat, too. On Dec. 2, 1941, German tanks were 14.7 miles from Moscow’s Red Square. America was only at war when Stern died in 1942 because the Japanese had attacked them.

It was unimaginable that the Americans would intervene on behalf of the Jews in the distant Middle East—indeed the U.S. only lifted its total weapons embargo on Israel in August 1962!—to allow the sale of defensive antiaircraft missiles, seven years after the Soviets had agreed to deliver bombers to Nasser’s Egypt (part of a huge Soviet weapons gift package misrepresented as “Czech” at the insistence of the CIA to avert hostility from their own man Nasser: That always-wrong agency was betting on Nasser’s mighty Arab nationalism rather than on seemingly puny Israel).

When Avraham Stern was killed, the communists still gave all their loyalty to Stalin. According to Ben-Gurion and the majority of Jewish leaders in Palestine, Churchill was still the best bet the Jews could have, even after the exposure of his crass duplicity toward the Yishuv. Having vehemently condemned the May 1939 White Paper to please his Jewish benefactors while out of office and short of ready cash, Churchill refused to change the policy once he became prime minister—thus denying escape from death to millions, and incidentally preventing my father, mother, two brothers, and myself from leaving Arad, Romania, to reach safety by a comfortable Orient Express ride to Istanbul and thence Haifa. A 5-inch-by-2-inch Palestine entry slip was enough to obtain Bulgarian and Turkish transit visas, but the British refused to issue them, even in 1944—by which point detailed eyewitness accounts and impeccable documentation of the operation of every part of the Nazi killing machine had reached London and Washington.

In spite of all that, on the evidence available at the time, Ben-Gurion was still mostly right and Avraham Stern was still mostly wrong. The British did eventually, and very reluctantly, agree to the U.N.’s termination of their mandatory rule on May 15, 1948, thus allowing the Jews to fight for their state. The qualifier is necessary because a factor in the British decision was the terrorist attacks inspired by Stern, including the July 22, 1946, bombing of the British headquarters in the King David Hotel whose 91 killed set a deadliest-attack record that lasted for decades.

It is only in more recent years that documents have emerged which prove that the British—meaning the then immensely authoritative Imperial General Staff whose eminence increased even more once Churchill was voted out of office on July 5, 1945—were determined to remain in Palestine, contrary to their representations to the Jewish leaders and the U.N. In fact, they had worked out an operational plan to do exactly that: They would equip the Egyptian army of their obedient liege King Farouk, and the Iraqi army of their obedient liege King Faisal II with field artillery, tanks, and combat aircraft, and they would send armored cars, field artillery, and excellent British officers to command the Arab Legion of their liege King Abdullah of Jordan. The Jews would be allowed no weapons at all—not even revolvers. Faced with the irresistible advance of the Arab armies, they themselves would plead for British protection, thereby ensuring the prolongation of British rule.

The General Staff documents reveal systematic strategic logic at work with no trace of antisemitism. British staff planners accepted that India, Burma, and Ceylon would soon be lost, but asserted that the Persian Gulf had to be kept because its oil revenues were essential to fund Britain’s reconstruction (aside from much housing stock lost to Nazi bombers, the machinery in British factories was worn out by wartime production).

Britain’s postwar recovery, the General Staff planners believed, would require continued control of a chain of air bases from Cyprus and the British-controlled Canal Zone to Iraq and Bahrain via the Negev, the southern desert that constituted the largest part of the U.N.-drawn map of the future Israel. The Jewish state therefore could not be allowed to become independent on May 15, 1948, except for a narrow coastal strip above the Negev, where a few hundred thousand Jews might live under British protection.

The Labour government that followed Churchill’s wartime coalition was fully engaged in building a land fit for heroes and had no time or inclination to interfere with the Imperial General Staff plan—and if they had intervened it would scarcely have changed anything. Labour Prime Minister Clement Attlee (Churchill’s “modest man with a lot to be modest about”), happened to be a very quiet but coldly determined and absolute antisemite as well as an anti-Zionist. This fact was little known at the time partly because of all the attention focused on the Foreign Office, which was led by the ex-trade-unionist Foreign Secretary Ernest Bevin, who was not a serious antisemite at all but only a loudmouth.

Bevin provided cover for both Attlee and the Imperial General Staff planners with his antisemitic outbursts. But the outburst most often cited against Bevin, of June 12, 1946—“There has been agitation in the United States … for 100,000 Jews to be put in Palestine [for] the purest of motives. They did not want too many Jews in New York”—actually originated wih James F. Byrnes, the U.S. secretary of state. Byrnes’ own policy—ferociously and very effectively enforced—was likewise to deny any weapons at all to the Jews, thereby furthering British plans.

Byrnes’ policy persisted unchanged under his certifiably nonantisemitic successor George Marshall (who had pressed for opening the gates to Jewish migrants into the U.S.) even after Israel’s independence on May 15, 1948, regardless of the inherent right of any sovereign state to defend itself. Had weapons not arrived by precarious DC-3 flights from the Czech Republic via Yugoslavia with the consent of Josef Stalin, who was out to embarrass the British Empire, the Jewish state would have been defeated, with the survivors rescued only if British rule persisted.

As it happened, the Jews turned out to be much better fighters than anyone had anticipated, but their 1949 victory on all fronts was only a setback for the Imperial General Staff, whose unquestioned authority did not wane until the 1956 Suez debacle.

Two bundles of heretofore overlooked documents prove that Avraham Stern was right in not trusting British declarations that they would end the Mandate and allow the Jews to establish a state, even within the shrunken borders envisioned by the U.N.

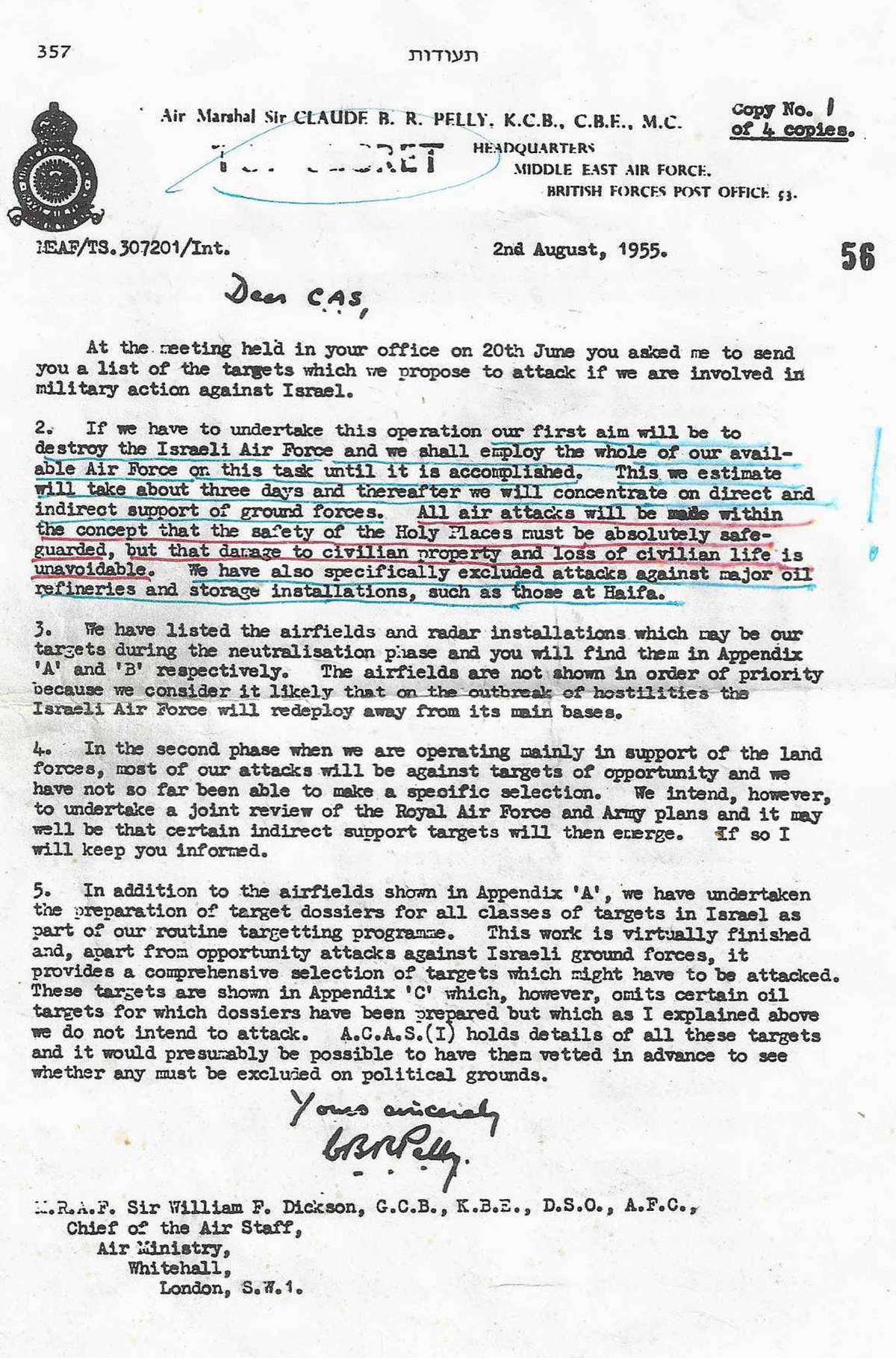

First, there are the “Operation Cordage” documents, which envisaged a terrorist attack on Israel that would provoke Israeli retaliation against the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan. The Israeli response would allow Britain to activate its commitment to defend the Hashemite Kingdom under the 1946 Treaty of London. This would provide the excuse for the British to launch all-out air attacks by the Royal Air Force from its Cyprus base and by the Fleet Air Arm from carriers, in order to destroy all Israeli air force and army bases, headquarters, and depots. (At the time, the British Air Force could do that and more.) As soon as Cordage was executed, the disarmed Israelis would be forced to beg for British protection, because they would be so weak that even the small Lebanese army could invade, along with the much stronger Syrians, Iraqis, and still then British-officered Jordanians.

The other set of documents describes the U.S.-U.K. Plan Alpha worked out in 1955 by Francis Russell of the U.S. State Department and the leading Arabist of the British Foreign Office, Evelyn Shuckburgh (who would suffer acute stomach pains whenever forced to concede a very rare audience to Israel’s ambassador). Presented by Prime Minister Anthony Eden in his November 1955 Guildhall speech, Alpha would detach the Negev—yes always the Negev—from Israel to give it to Egypt—which was still then, if not for long, “British Egypt,” complete with army and air force Canal-side bases, garrisoned by 70,000 British troops.

It was only Nasser’s betrayal of his CIA would-be handlers to seize control of the Suez Canal, and the subsequent 1956 Suez War—Israel’s Sinai campaign—that turned the tables. The British attacked Egypt instead, resulting in Eden’s resignation, lifelong sorrow for Shuckburgh, and the start of the wars that would lead to the Egypt-Israel peace treaty and present cooperation, thereby realizing Stern’s hope that Arab and Jewish nationalists could be allies.

So who was right?

The Cordage documents attached were provided by the historian and preeminent broadcaster Dr. Isaac Noy, z.l., May 2022. Anat Stern corrected errors in an earlier draft.

Edward N. Luttwak is a contractual strategic consultant for the U.S. government and an author.