Israel’s Failure to Support Syrian Rebels

A dispatch from the Golan Heights, where the Jewish state’s confounding political and military policy plays out in the lives of Syrians looking for hope of any kind

The worst injuries Raed sustained during his six years fighting the Assad regime were in late 2014. The car he was driving was hit by a mortar shell, leaving him with two broken legs and severe burns to the face and arms.

“I found myself in a field on the Israeli side, a few feet from the border fence. Injured people were all around me,” Raed recalled. “I woke up in pain, screaming for anesthetics. An Israeli officer approached me and asked why I was screaming. I said: ‘Send me in [to Israel]! Why have you left me here?’ The soldier pointed to a woman next to me whose leg had been amputated and said: ‘This women isn’t screaming. You’re a man, why are you?’”

An argument ensued, ending with Raed being sent back to Syria for treatment. It was his fourth time entering Israel after being injured on the battlefield. “He was making fun of me,” Raed explained. “I never returned to Israel for treatment after that.”

In the grand scheme of things, this anecdote may seem trivial. But in the aftermath of rebel capitulation to the Assad forces along the Israeli border in early August, it resonates with the bitterness of humiliation and betrayal.

“Many people relied on Israel. In my unit, people believed the Assad regime wouldn’t dare enter the buffer zone, that it would be a red line for Israel. I told them that’s a lie. No way. There are agreements between the countries, and [Israel] will allow the regime to return to Israeli-Jordanian border. I would jokingly add that the regime will take the last spoonful of Syrian land.”

Sitting at a café in the Aksaray neighborhood of Istanbul, where Syrian refugees gravitate to buy shawarma sandwiches at Anas Restaurant and get a taste of home, Raed and his friend Jalal relived the dashed hopes of their failed revolution. It took Jalal three crossing attempts before he managed to enter Turkey. Two weeks earlier, he fled Quneitra on the first bus for the rebel stronghold of Idlib in northern Syria. The bus was commissioned for the rebels as part of a surrender agreement with the regime. On his first attempt to smuggle his way across the border—for which he paid a local smuggler $1,300—his group of 20 refugees climbed a steep mountain until he could proceed no more. The second time, the smuggler turned them back due to increased policing on the Turkish side. Finally, Jalal paid the smuggler an additional $1,200 for an easier route across. He and 25 others climbed a concrete border wall on ladders, then scurried to the Turkish town of Reyhanli. From there, they fled by bus to Istanbul through country roads.

“I should forget Syria. I can’t return,” he said. “Only Idlib is left [in rebel hands], and the regime could retake it. We don’t have anywhere to return to. I will start a new life far away from Syria.”

‘If Israel wanted to help us, it would have offered weapons. What did it offer? Sugar, rice, tea.’

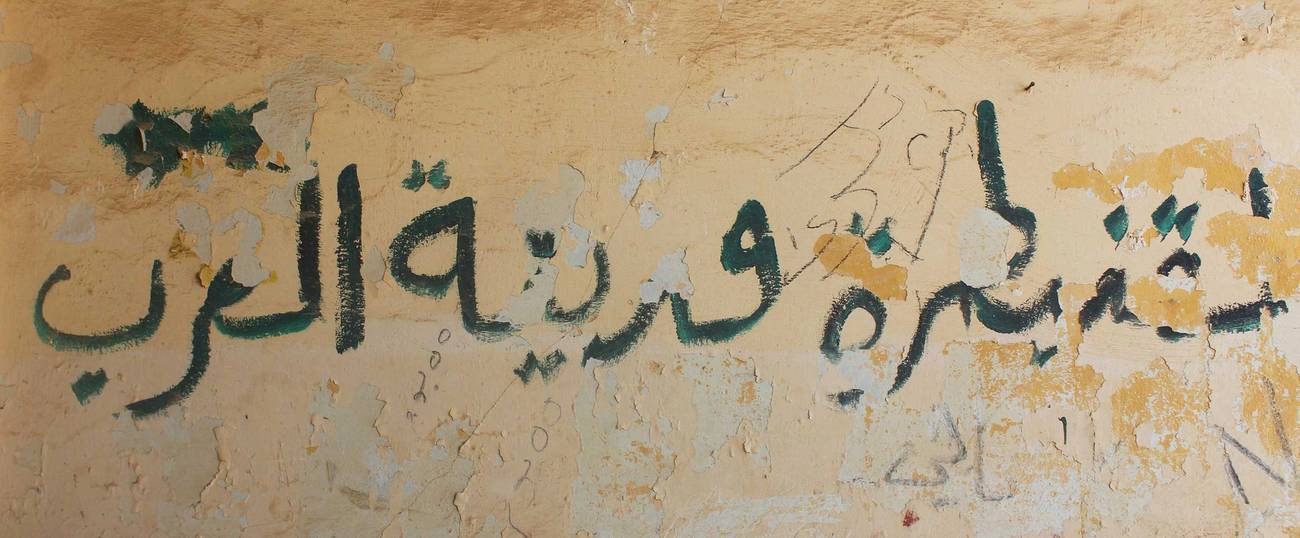

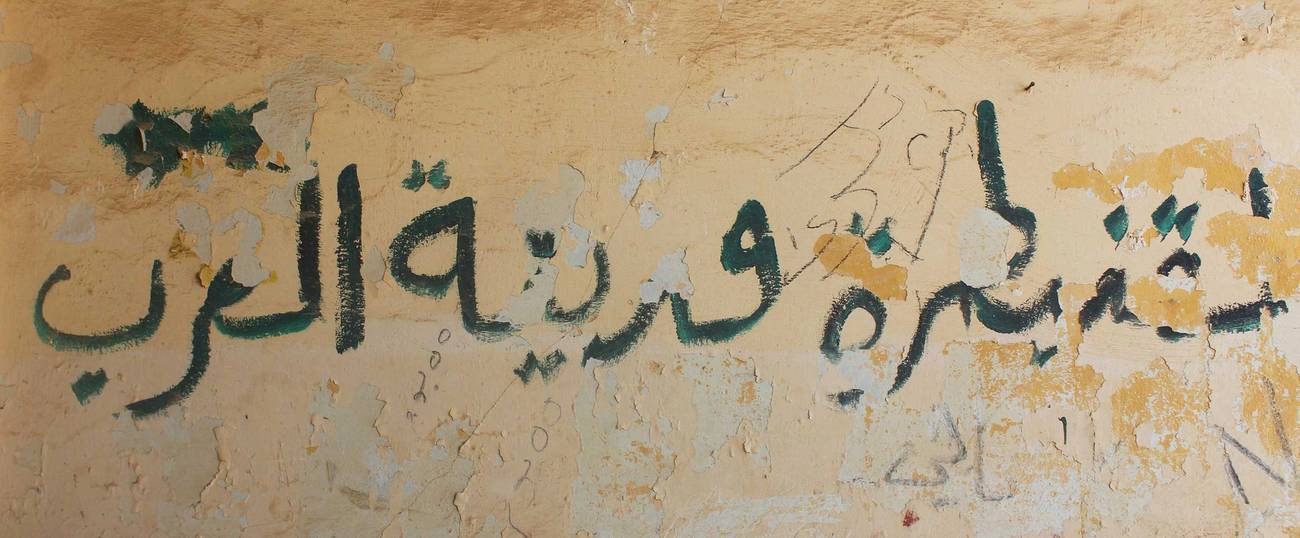

Seven years after their families first took to the streets of south Damascus demanding better wages and human rights, they are now defeated men, partisans of a lost cause that was once full of hope for a better future for Syria—and perhaps better relations between the Syrian people and Israel. Rebel groups affiliated with the Free Syrian Army captured the Quneitra province along the border with Israel from the Assad army in February 2013, and quickly started to work with the Israelis. Jubatha al-Khashab, just across the border from the Golan Druze villages of Mas’ada and Buq’ata, was the first village in the province to fall to the opposition.

Jalal, a 23-year-old opposition activist and citizen journalist, arrived at Jubatha in early 2013 from the battlefields south of Damascus. In the village, he worked with a small group of journalists that called themselves Al-Quneitra Voice, distributing their footage to Arab satellite channels like Al-Jazeera and Al-Arabiya. Jalal said the townspeople had high hopes from Israel, which sent them fuel for their generators and distributed drinking water. In 2016, the IDF’s newly established Good Neighborhood Directorate began sending tons of dry food and medical supplies.

“Jubatha really collaborated with Israel,” Jalal said. “People in the village believed it was impossible for Israel to forsake them, but that was an illusion. Israel disappointed us a lot.”

***

Jalal’s family originates from a village in the central Golan Heights, captured by Israel in the 1967 Six-Day War. Today, Moshav Yonatan, population 662, sits on its ruins. In the early days of the revolution, Jalal attended a meeting between his clan elders and a delegation of Assad’s Baath Party which came to absorb their anger. His family members accused the regime of handing over the Golan Heights to Israel and demanded compensation for property lost in the war. No reply ever came, and the impoverished tribe was soon on the streets, shouting “the son of a bitch sold the Golan.” “Our morale was very high,” he recalled. “We’d broken the fear barrier.”

Ever since he was young, Jalal loved cameras. But it was on an old Nokia cellphone that he used to record the first anti-government demonstrations in April 2011, when he was just 17. Soon, he would split his time between videography and the battlefield, where he delivered ammunition to fighters in the trenches.

The Palestinian group Hamas, its headquarters in Damascus, sent fighters to join the rebels too, Jalal recalled. “They were fierce fighters,” he said, noting one man in particular, Abu-Ahmad Mushir—believed to be the personal bodyguard of Political Bureau chief Khaled Mashal. Once, Jalal saw Mushir fire an outdated anti-aircraft missile at a regime helicopter and miss. Mashal abandoned Damascus and his patron Assad in January 2012.

For many rebels, the revolutionary dynamic bred an understanding that Assad’s belligerent stance against Israel was nothing but a charade. “Forty years of so-called resistance have given us nothing,” he said. “On the contrary, everything moved backwards. The Syrian army was weak. In 2014 and 2015 Israeli aircraft would fly over Syrian army units with impunity. At some point the army started firing at them with machine guns. Seriously, can a machine gun down a plane?”

Assad’s inability to challenge Israeli incursions should have given Jalal and his friends pause to realistically evaluate the Israeli stance vis-a-vis the rebels. They also knew, or should have known, that Israel was unsentimental in leaving behind many of its former allies from the South Lebanon Army (SLA) when they withdrew from Southern Lebanon in May 2000. But Syrian contact men, the so-called collaborators tasked with coordinating the transfer of injured fighters and civilians to Israeli hospitals, painted a rosy picture of life in Israel that for some oppositionists was too alluring to ignore.

“The patient coordinators would travel to Israel and return with news of how good life is there,” Jalal said. “We asked them why Israel won’t open its borders to us. I thought I could go study in Palestinian universities. Many people hoped to export goods to Israel.”

But others, like former combatant Raed, were more skeptical. “A verse in the Quran says: ‘Never will the Jews or the Christians approve of you until you follow their creed.’” he said. “Most people here didn’t count on Israel for help. We knew Israel considered us terrorists. The [Assad] regime defended Israel for 40 years, and Israel believes we just came to disrupt things on the border.” When Israeli food products began entering Syrian villages, he burned them, encouraging others to do the same.

“If Israel wanted to help us, it would have offered weapons,” he told me. “What did it offer? Sugar, rice, tea. Do the Syrian people really need tea and sugar? I need something I can use to fight the Iranian expansion.”

Ahead of battles with the regime, Raed’s rebel group would send Israel detailed requests for ammunition through the Syrian coordinators. Israel would habitually reply with offers of money for rebels to purchase arms in the free market, where very little ammunition existed. The assistance Israel did offer was nothing but an attempt to hedge its bets in case the opposition somehow prevailed over Assad, Raed now realized. “We the rebels could have won, and Israel wanted to have a stake in that.”

Nevertheless, Raed did not refuse medical treatment in Israel when offered to him throughout the war, understanding full well, he says, that Israel was doing so for its own reasons. “We were treated in Israel because we had to be,” he says. “Jordan didn’t help us. During the early stages of fighting, we implored Israel to send us bandages and medication, but they gave us nothing. Later, we in the various fighting units designated a representative from the Al-Furqan Brigades named Abu-Diaa and he coordinated the transfer of wounded men.”

Raed said Israel did not ask questions about the identity of the wounded fighters it admitted. But in hospital, he was asked more than once “what Israel meant to him.” He assumed his questioners belonged to Israeli intelligence. “I would tell them Israel doesn’t mean anything to me,” he recalled. “Assad is my main enemy, then Iran, and we’ll see about the rest later. In the future, there may be battles with the Jews, but at the moment, the fight against Shia expansion is the most important thing. Shia expansion is the most dangerous thing for us in Syria.”

Jalal and Raed point to regime attempts to establish Husseiniyat, Shiite learning centers, in their province—attempts they say have been thwarted by the local population. Jalal said he expected the menace of Iranian influence to spur Israel into action.

“I’d hoped Israel would defend the area, intervene, stop the war,” he said. “But as soon as the battle for Quneitra began, our hopes were dashed and the cards were exposed: Israel was in coordination with the regime against the people. In the final battles, regime and Russian aircraft struck villages like Quseiba and Nasiriyah situated no more than 1-1.5 miles from the armistice line with Israel. It became clear to me that Israel prefers Iran on its borders, because as soon as we leave, Iran will enter.”

Confident that “no dictator lasts forever” and that Assad’s rule will come to an end only in the distant future, Jalal nevertheless insists that Israel has committed a grave mistake by siding with the strongman.

“There could have been better relations between us,” he said. “In 50 or 60 years Assad will be gone, but the Syrian people will remain. Israel bet on Assad, but it will be a losing bet.”

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Elhanan Miller (@ElhananMiller) is a Jerusalem-based reporter specializing in the Arab world.