Trinity: 2015

The nuclear age began 70 years ago today

One of history’s most important dividing lines was etched in a remote and desolate part of New Mexico exactly 70 years ago today, and the world knew nothing about it at the time.

Ask most people when the nuclear age began and they will probably answer Hiroshima, Aug. 6, 1945. It did not. Three weeks earlier, on July 16, the world’s leading scientists, including Lawrence, Fermi, Teller, and, of course, Oppenheimer, assembled in the middle of the night at an abandoned ranch near Alamogordo. Along with hundreds of engineers and soldiers, they huddled in anticipation, wondering what, if anything, their long labor to create a nuclear bomb would produce.

Years later, Norris Bradbury, the Director of the Los Alamos National Laboratory from 1945 to 1970, put the entire event in context: “Most experiences in life can be comprehended by previous experiences. But the [first] atom bomb did not fit into any preconception possessed by anybody.”

Quite simply, no one had ever seen anything like it because nothing like it had ever taken place.

Three days before, a convoy of army trucks and jeeps left Los Alamos with the test device, called simply the “Gadget,” under the cover of darkness. J. Robert Oppenheimer, the brilliant and complex director of the project, gave the site its code name, Trinity, from a poem by John Donne. “I may rise up from death, before I’m dead.”

The night before the scheduled test, Oppenheimer’s frayed nerves were agitated further when he read the results of an experiment indicating the bomb could prove to be a dud. His weight was down to 116 pounds from overwork and uncertainty, and his clothes barely hung on him as he chain smoked cigarettes and drank black coffee.

On the other extreme, Nobel Laureate Enrico Fermi wondered aloud if the bomb would ignite the atmosphere. Some of the physicists started a betting pool guessing the bomb’s kiloton yield (its TNT equivalent). The cost to enter was one dollar. Anderson bet low at zero and Teller, the optimist, bet high at 45 kilotons.

At midnight, the base camp was suddenly pummeled with high winds, lightning, and a tremendous downpour. Gen. Leslie Groves, in charge of the military branch that oversaw the Manhattan Project and was therefore used to getting his way, lashed out at his forecaster shouting: “What the hell is wrong with the weather?”

The meteorologist assured him that the storm would pass by 5 a.m. It did, and in the predawn sky, stars appeared as the countdown commenced to the projected time of 05:30.

No one actually pulled a switch or pressed a button at the moment of detonation. It was all set on an automatic timer. The only way that Donald Hornig, a Harvard scientist and the man in charge of setting the timer, could stop it in case of emergency was to cut the wires with a knife that he held in his hand.

The one overriding worry that pervaded everything was that the countdown would go down to zero and there would be a terrible silence in the desert.

Teller, the Hungarian immigrant and prime physicist on the project, later recounted that at first, he just saw a tiny point of light and wondered to himself: “Is that all?” But he then noticed the point of light quickly rising in the sky and expanding logarithmically. That was followed by an earth-shattering thunder, which bounced back and forth, echoing through the valley.

Philip Morrison, a 30-year-old physicist who had worked on the explosive element of the bomb, remembered shivering through the cold of the desert night when suddenly he felt the heat of the sun all over his body, only the sun had not risen.

Frank Oppenheimer, standing next to his brother, heard him say quietly under his breath, to no one, “It worked.”

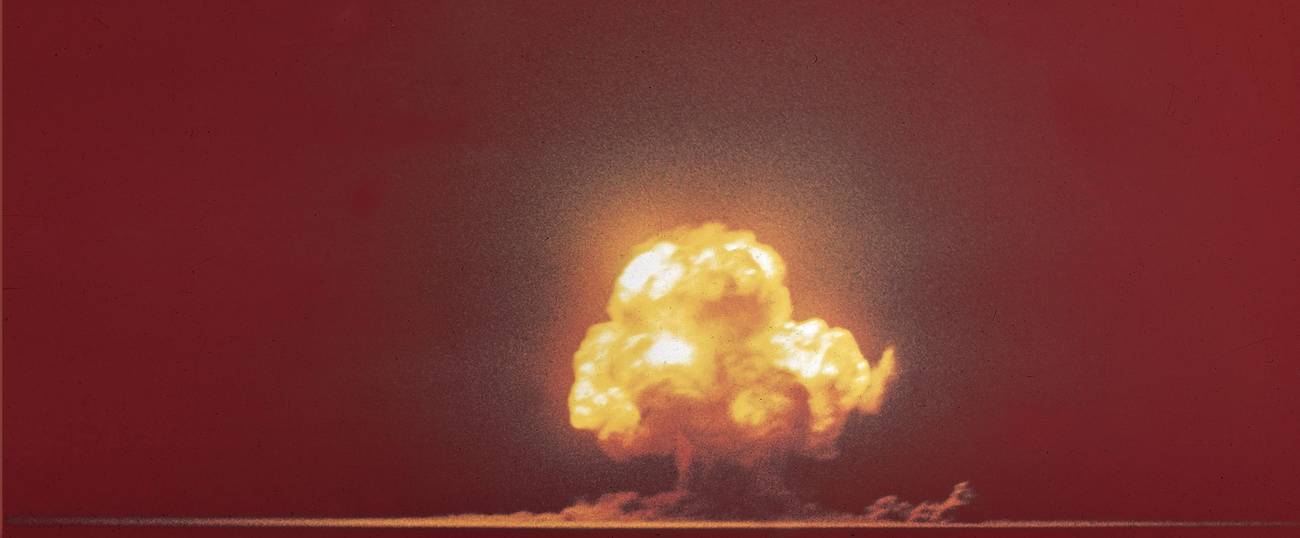

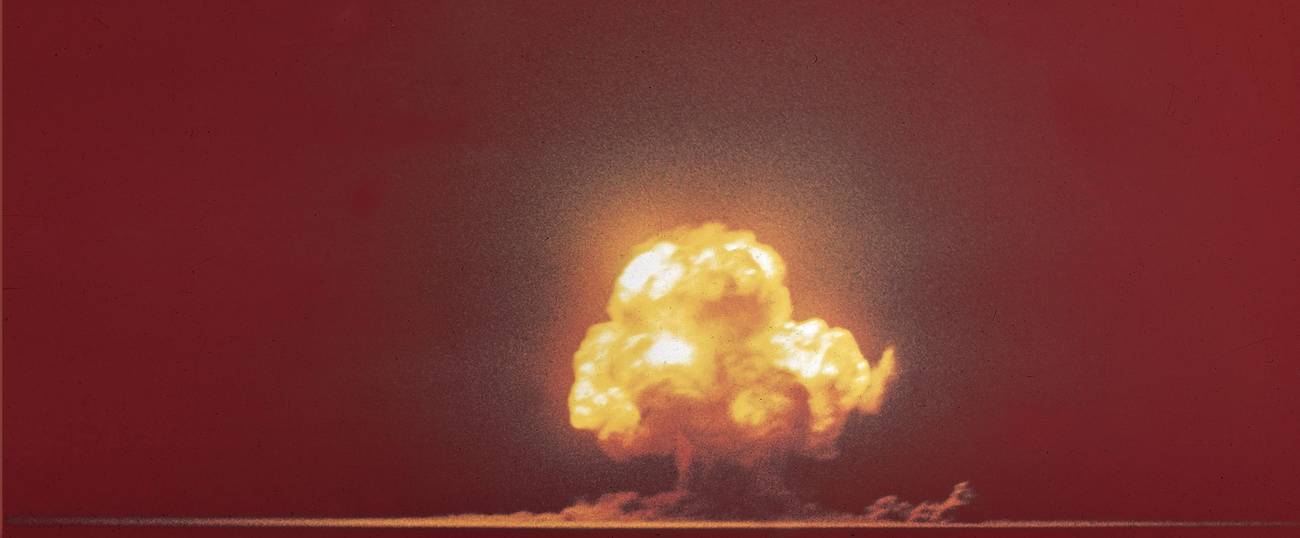

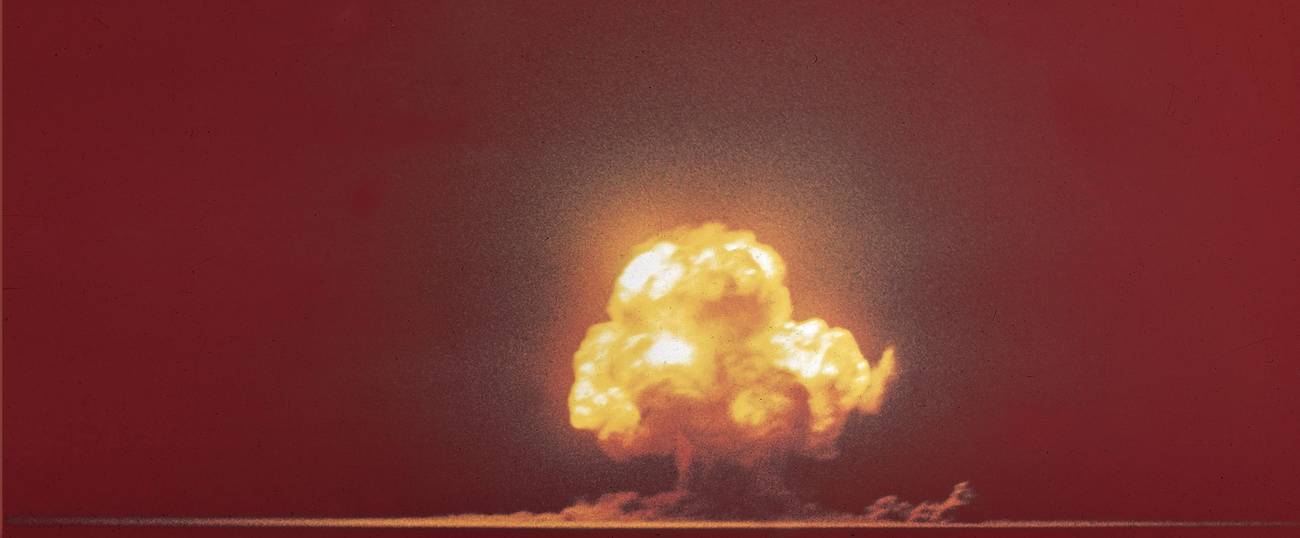

At exactly 5:29:45 a.m., Mountain War Time, the New Mexico sky lit up with a scalding white light that measured 18.6 kilotons and quickly turned into an ominous mushroom cloud—so familiar now—rising in the sky. (The betting pool went to I. I. Rabi, who arrived late and had to take 18 kg because that was the only number that was left.)

Later that day, President Harry Truman, in Potsdam for the postwar conference in Europe, was handed a telegram from Secretary of War Henry Stimson that would alter the battle in the Pacific and everything thereafter: “Operated on this morning. Diagnosis not yet complete, but results seem satisfactory and already exceed expectations.”

The distance between the first test at Trinity and its usage at Hiroshima was just 21 days. Critics have condemned the United States ever since for using the bomb on civilians. The fact that cannot be argued is that it ended a horrific war; it didn’t start one.

The United States held a complete world monopoly on nuclear weapons for exactly four years. In that time, it never once threatened another nation, even as the Soviet Union took control of all of Eastern Europe. That monopoly ended when the Soviets detonated their first nuclear device on Aug. 29, 1949, with information gleaned from spies at Los Alamos. One of these was the young German physicist Klaus Fuchs.

Over the next four decades, billions of dollars would be spent by both superpowers on better delivery systems—fleets of bombers, missiles, submarines—as well as defense and warning systems that were constantly updated as the stand-off was set in place.

Tough realists faced each other with their fingers on the trigger. That’s a dangerous scenario, but because the people on both sides understood whom they were dealing with across the table, it worked.

Oddly, the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1990, which brought an end to the Cold War, did not erase the fear of nuclear war. Just the opposite. The world entered a new, more complex era, with countries like Pakistan and North Korea gaining nuclear capabilities. Now Iran, one of the world’s leading sponsors of terror, is poised to gain access to the most deadly technologies that human beings have ever invented.

Nuclear technology has not really changed since Trinity, but what has changed—drastically changed—is U.S. policy toward its containment, as evidenced in this week’s deal with Iran. It is impossible to imagine men like Paul Nitze, Henry Kissinger, or George Shultz dealing with the Iranians as President Barack Obama and John Kerry have from the start. At each turn, the Iranians balked until the United States, seemingly so desperate for a deal, gave in—on break-out time, on the number of centrifuges, on open inspections at Iranian military facilities, on Iran’s ballistic missile program. Strangely, the strength in the negotiations seemed to reside with Iran.

When Henry Stimson first briefed Harry Truman on the existence of the bomb, just days after FDR’s death, Stimson voiced concern that after the United States monopoly ended, the world’s technical achievement would outpace its moral development. Today, that may sound patronizing to some. Yet it is striking that in the face of efforts to bring the Islamic Republic of Iran into the community of nations, Iran has threatened to start a nuclear war, repeatedly, by promising to wipe a U.N. member nation from the map. Seventy years later, Stimson’s words seem frighteningly accurate.

Warren Kozak is the author of LeMay: The Life and Wars of General Curtis LeMay.