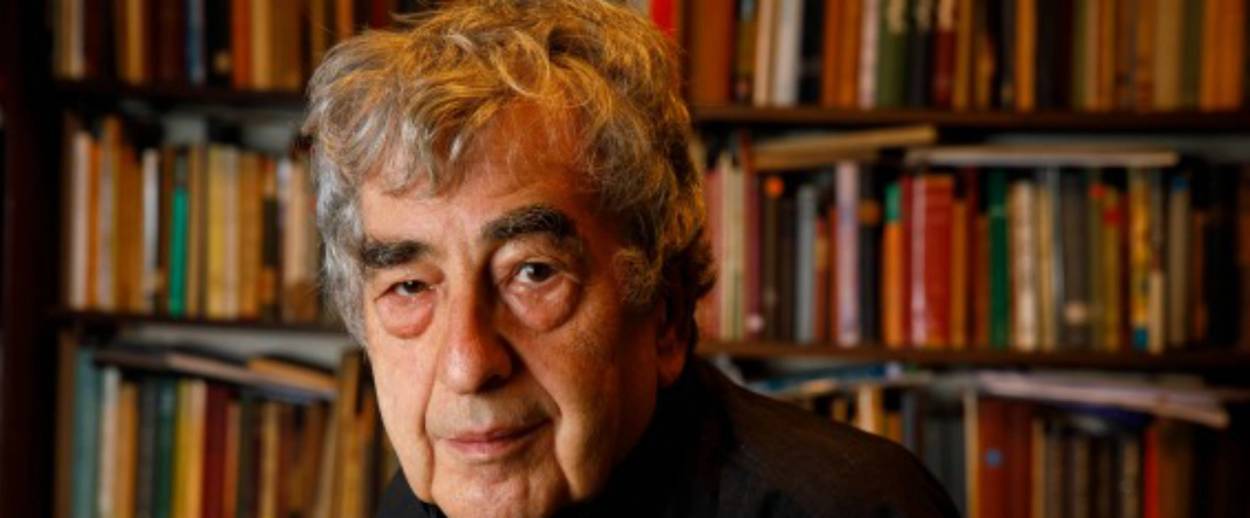

Haim Be’er’s Language of the ‘Jewish Bookshelf’

Appearing in English for the first time, a vignette from Haim Be’er with an introduction by the translator

A vignette by the great Israeli writer Haim Be’er has been newly translated into English and is being published for the first time today in Tablet. The following commentary by the essay’s translator Jeffrey Saks serves as an introduction to Be’er’s body of work, and the themes and style of the excerpted piece.

Haim Be’er is likely the most significant Hebrew author you don’t know—but should. International fame for Israeli authors is a function not only of their worth and talent but just as often, that of their translators (and the vicissitudes of the publishing industry). Be’er began his career as a journalist, essayist, and editor, and since 1979 has published seven novels, alongside works of literary criticism and memoiristic collections of stories of his life among books. Only two of his works have appeared in English—the most significant being Hillel Halkin’s fine translation of Be’er’s debut novel Notzot under the English title Feathers.

It is Be’er’s distinct literary style and narrative voice, which poses the translator’s challenge. As the late Alan Mintz noted of Be’er’s writing:

[It] is suffused with antic echoes of sacred texts in a way that makes it a pleasure for any Hebrew reader with a modicum of Jewish literacy. That Be’er can pull all of this off makes him a unique figure in the landscape of today’s Israeli literature, in which religious themes are usually regarded as fruit of the poisonous tree. He is one of the few Israeli writers or public intellectuals who draw upon a wide range of traditional Jewish sources while still managing to gain the attention and admiration of a serious reading public that is preponderantly located on the secular side of a deeply divided national culture.

Be’er’s distillation of the language of the “Jewish Bookshelf” into contemporary Hebrew literature is reminiscent of Bialik’s description of Mendele Mocher Seforim, who “took, drop by drop, whatever he found in the treasure-house of the Jewish people’s creative spirit and he gave it back, and in a refined form, to the same treasure-house.” Yet this is precisely what flummoxes translators attempting to produce a readable English text. It is not surprising that only one as skilled as Halkin was equal to the task (and even then, the manuscript languished for over a decade before finding a publisher), for he had honed his abilities in translating S.Y. Agnon—an author who poses similar problems.

A comparison between Agnon and Be’er is particularly relevant, as the latter freely recognizes the influence of the former. But beyond matters of style, there is a deeper connection. Aharon Appelfeld described Agnon’s influence on his own writing as less a matter of form and more one of focus: “Most of my generation [of fellow Hebrew authors …] invested a huge amount of effort into suppressing and eradicating their past … But I, for some reason … retreated into myself. For this, Agnon served as an excellent role model. It was from him that I learned how you can carry the town of your birth with you anywhere and live a full life in it.”

Like Agnon and Appelfeld, Be’er has used the city of his youth for the mise en scène of his most important novels. Unlike Agnon and Appelfeld, who were products of Eastern European childhoods, Be’er was born in Jerusalem in 1945, where he lived in the ultra-Orthodox Geulah neighborhood. Secular Tel Aviv’s suburbs have been his home throughout his entire adult life, yet Jerusalem has remained his alte heim and his childhood there continues to serve as a literary source to be mined.

The vignette for Sukkot, published today in Tablet in a first-time English translation, is taken from his book Kesher LeEhad, a collection of non-fiction stories of “journeys, places and people in Jerusalem,” published last year in Hebrew. This story, which Be’er presents as occurring in a Me’ah Shearim bookshop qua etrog fair in 1963, contains a sidebar about his only encounter with Agnon. This anecdote had previously been recounted, with slight alterations, in Be’er’s early novel, Havalim (in a problematic translation as The Pure Element of Time). This twice-told tale, appearing in both a work of fiction and of autobiography points to the way in which Be’er (whose chosen family name means “well”) persists in drawing from the waters of his youth.

The main action of the story comes from young Haim’s encounter with the revered saint of Jerusalem, Reb Aryeh Levin (1885-1969). The rabbi’s model of charity, kindness and righteousness on the eve of the holiday resonates with a well-known Agnon tale, and again highlights the intricate weaving of fact and fiction, of Be’er’s contemporary prose with earlier Hebrew literature, and the intertextual matrix of the classical Jewish Bookshelf. A collection of wonder tales about Reb Aryeh by Simcha Raz appears in English as A Tzaddik in Our Time. As a young man a mentor once drew my attention to the work, which like many rabbinic biographies is cast in a hagiographic glow, and commented: “If only one out of every 100 stories in this book actually happened, Reb Aryeh would still count as the greatest soul in a century—how much more so that each and every story in it is true!”

Rabbi Jeffrey Saks is the founding director of ATID and its WebYeshiva.org program, and is the Director of Research at the Agnon House in Jerusalem. Some of his translations of Agnon’s stories have appeared in Tablet and in the Toby Press’ Agnon Library.