Kate Heidecker remembers when everything changed in Kingston, New York. Now in her late 30s, Heidecker was born and raised in this small city of 23,000, tucked between the Catskill Mountains and the Hudson River 90 miles north of Manhattan. She was in middle school in 1995 when the city suddenly faced a major catastrophe.

That year, the leadership of IBM, which established itself in Kingston in the 1950s and employed 7,100 local residents, abruptly announced that it was leaving the city. As a one-company town, Kingston residents lost more than 20% of their income after IBM pulled out of Ulster County—with those still living there making 25% less than the median national income. Twenty-five years later, the effects can still be felt. Ulster County today suffers from drug trafficking, gang feuds, and intense poverty; over 40% of county residents struggle to pay their bills and put food on the table.

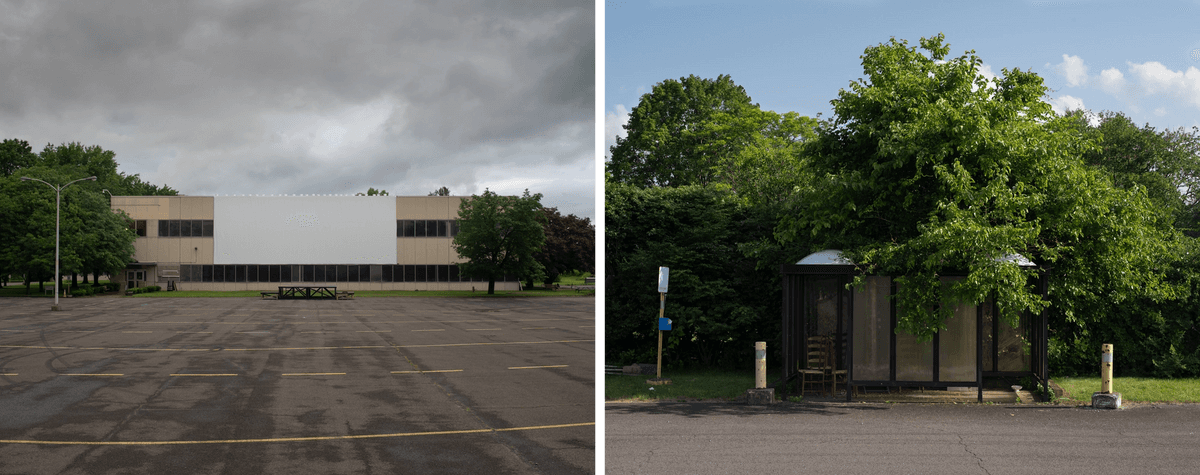

One afternoon in May, Heidecker and I stood on the former campus of the company that made—and unmade—her hometown. “This place has a lot of emotion for me,” she said. “Kingston people have very strong feelings about it still. Everyone moved away. I lost a bunch of friends all at once.” Some of her classmates had parents who won coveted reassignments to IBM locations in other parts of the country. Thousands of others were left behind.

“But I think this is why the redevelopment is so great,” Heidecker pivoted. “It’s going to change the narrative, you know, and change how people feel about this place.”

Heidecker is now the deputy director of the Economic Development Department and spokesperson for Ulster County’s major real estate project—a “once in a generation opportunity,” as it was called in a recently published vision plan—to remake the 82 acres of the campus into a high-traffic hub for new businesses, artists, and innovative makers of food and culture.

In 2019, the county had taken over a large chunk of the campus from the post-IBM property owner, the real estate developer Alan Ginsberg, after he failed to pay millions in property taxes. The repossessed property included the 400,000-square-foot, three-story structure that Heidecker and I walked through together—a portion of the compound that most people around Kingston refer to simply as Tech City. IBM produced a wide variety of technology and military communication systems here, from terminals for air defense systems to electric typewriters that rolled off a 2-mile-long assembly line.

As we made our way through the building, we walked underneath dislodged ceiling panels suspended at odd angles from above. Sunlight crept in through the hundreds of tall windows, their filmy glass encrusted in years of grime. We climbed the stairs past a coffee can holding a dead rodent and reached the roof, looking out over the gorgeous green sprawl of the Catskill Mountains.

“One of the first things that we plan to do, once the building is up and running again, is reach out to anybody that was impacted by IBM. The locals here that saw that devastation,” Heidecker said. “Of course we want to reach the whole community at large, but I think starting with those people is really important to healing this space.”

Though more than 20 businesses and organizations in the region have proposals for reimagining Tech City, everyone already knows who has the winning bid. A consortium known as BLUEprint—promising as many as 300 new jobs within five years and popular crowd-pleasers like a skatepark and an arts center, besides more radically ambitious projects like a grain mill and a new food distribution system—will go through the motions along with other applicants. But BLUEprint is considered the obvious winner, so much so that parts of its proposal are already being implemented. In June BLUEprint even kicked off its takeover of Tech City with a robot-themed dance party, complete with bartenders and DJs.

BLUEprint, as some in Kingston now realize, is just one of the many new marquee endeavors of the NoVo Foundation, the nonprofit entity founded by Peter Buffett, the son of Warren Buffett. The NoVo Foundation is one of the richest philanthropic operations in the world, endowed every year with a tranche of Berkshire Hathaway stock earmarked by the elder Buffett, Berkshire’s founder, for each of his children’s philanthropic foundations. NoVo is run by Peter and his second wife, Jennifer, with whom he shares the CEO title. The Buffetts operate the foundation out of a modest historic stone building in Kingston, where the two have lived since 2010.

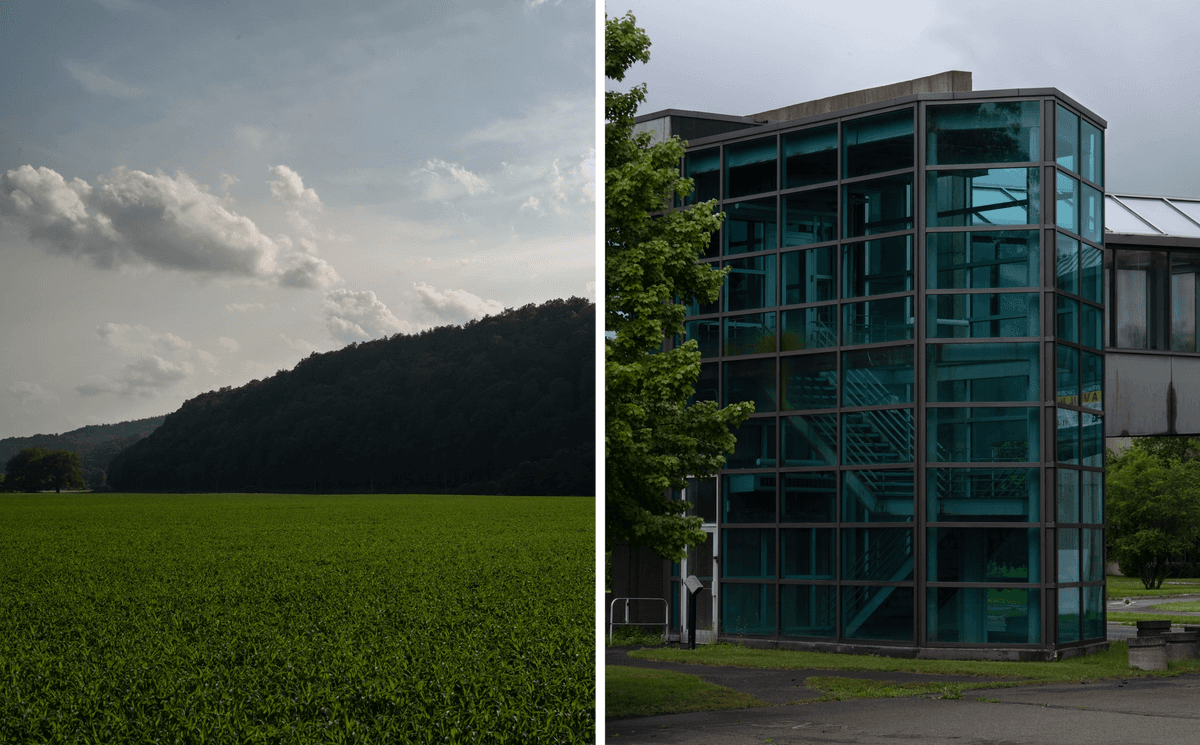

The couple’s investment in the town began nearly a decade ago, a few years after they moved there. In 2014, NoVo paid $13 million for Gill Farm, a 1,500-acre family crop farm that belonged to John Gill, a second-generation farmer and Kingston personality who tended to leave an impression on people. Jovial and intelligent, he was a guest on The Colbert Report in 2010 and a visible emblem of the area’s ties to small family farming. “They literally bought the heart and soul of Ulster County” that day, a longtime resident and former NoVo Foundation collaborator told me. “Everything else is just icing on that cake. It was the largest agriculture producer in the county, and John Gill was a personality larger than life.”

Few initially saw the acquisition as a problem. The NoVo Foundation renamed the property the Hudson Valley Farm Hub and promised to fight systemic food scarcity by making it into a new distribution center for Hudson Valley’s agriculture. The old Gill Farm would still produce vegetables while taking its crops fully organic, training aspiring farmers in the trade and carrying out grain trials to develop more resilient crops—all things John Gill had wanted but couldn’t afford to do himself.

The Farm Hub was a big purchase, and the NoVo Foundation had the money to make “an open-ended commitment” to support it, with at least $89 million spent and another $47 million promised to the Farm Hub and its programs over the next several years. And that was only the beginning.

To date, at least $160 million, and perhaps more than $250 million, has been spent by the NoVo Foundation to purchase real estate, construct buildings, and launch a kaleidoscopic suite of projects that are more analogous to Celebration, the Walt Disney Corp.’s master-planned Southern Florida community, than any familiar form of philanthropic giving.

NoVo is the predominant or exclusive funder of Kingston’s local news media and radio station, a local printed currency, a 1,500-acre farm and produce distribution center, a food co-op, a museum, a think tank, a mutual aid network, a health care network, a hospital, the Kingston Land Bank, the YMCA, the community center, and dozens of nonprofits that are working on all imaginable forms of community projects. NoVo has made unusual grants to both the city of Kingston and Ulster County—unusual because it is picking up the tab for traditional government services; in 2018 alone it gave $4.1 million to the county and nearly a quarter of a million to the city of Kingston for routine operating expenses. During the pandemic, the county opened an emergency relief fund that within 24 hours received a $2 million anonymous donation. No one seriously considered the identity of the benefactor to be a mystery. If the Buffetts were to maintain their current spending pace over the next ten years, a conservative estimate would put their investments in Kingston at over half a billion dollars.

This unprecedented, top-down revolution has had varying effects on the people who live here. Some of those effects are clearly positive. No doubt the money for food pantries has put meals on the table for those who needed it, just as the grants for school programs and repairs to the local pool have made life better for those in the city. Yet over and over again Kingston residents and NoVo collaborators alike have expressed dismay about how NoVo has conducted so much of its business without public input. According to the NoVo recipients and NoVo collaborators I spoke to, a loose set of rules applies to Novo’s largesse—you don’t discuss your grants from NoVo, you don’t criticize NoVo in public, and you don’t speak ill of the Buffetts—lest you jeopardize your funding.

They’ve invested more money than the actual budget of the city of Kingston, without there being any sort of democratic process.

“On the one hand, I’d say, ‘Gee, we’re really fucked,’” the longtime resident and former NoVo Foundation collaborator told me. “But then again, it’s like, well, get more of that Buffett money, would you?”

For some, that’s precisely the problem: For a county without a solid economic base and persistent issues with poverty, food insecurity, and even public safety, linking Ulster’s fate to a single benefactor feels like a recipe for disaster—the same one it suffered when IBM left town.

“If you’re an intelligent person, you have to be at least a little bit wary of huge amounts of money coming into your county with no ability to leverage any longevity, or any kind of guarantee, or any sort of accountability,” one Kingston local and NoVo funding recipient told me. “My concern at this point is that they’ve invested more money than the actual budget of the city of Kingston, without there being any sort of democratic process. Whether or not we like the current city government, we get to vote for the mayor. We vote for the council, they allocate the money, and even if I hate everything they do with it at least I have the right to vote for them. This is a family foundation led by a billionaire literally creating a plan for a community that I live in, a plan to create this post-capitalist or whatever utopia in Kingston! And we have no say in what that plan is.”

Warren Buffett’s earned fortune was recently estimated to have topped $100 billion—but throughout his career he has managed to convey an image of a happy, regular, well-adjusted, normal, idyllic, very calm, totally supportive, thoroughly nurturing and modest family man living in the same family home in suburban Omaha that he bought in 1958, the year that Peter, the youngest of Warren’s three children, was born. Peter has said that he had only a vague awareness that the family was wealthy growing up, the family’s vacation house on Laguna Beach in Southern California being one indication.

Warren never wanted to overindulge his children: His oft-quoted wish was to bestow them with “enough so they can do anything but not enough so they can do nothing.” Though Peter had the promise of free college tuition, he chose to take a family gift of $90,000 at 19 and drop out after a few semesters at Stanford to pursue the life of a professional musician. In San Francisco with his first wife, he ran a jingle production company for local entities like the California Milk Advisory Board. He eventually moved into composition for more prominent advertisers as well as work on film soundtracks.

In Life Is What You Make It: Find Your Own Path to Fulfillment, Peter’s 2011 memoir, he wrote, “In my own mind I remain very much a working stiff—a composer and musician who, like most of my colleagues, is only as good as his last composition.” In a 2004 interview, Peter explained that life was challenging as a working artist. “You can’t chart what will come when. Bread on the table starts to get a little scary now.” Beyond the $90,000 worth of stock Peter cashed in as a teenager in 1977, he received an additional $300,000 gift from his father to fund his Native American rock opera. He also had Berkshire Hathaway stock worth at least $500,000, and, in 2004, six years before he published his memoir on lessons learned working hand-to-mouth as a commercial composer, he inherited $10 million after the death of his mother.

When Peter turned 48, however, everything changed.

In 2006, Warren Buffett announced he was giving away the majority of his vast wealth to charity, splitting it between the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and the three philanthropies overseen by each of his children: Peter with NoVo, and Howard and Susan Buffett, who each run foundations of their own.

Peter by then was married to his second wife Jennifer, the daughter of a Catholic family from Milwaukee whom he met one afternoon in a restaurant. Jennifer later described their initial encounter, in an interview the couple gave to Moon magazine, as “a soul recognition that we had work to do together.”

Warren Buffett’s initial gift to Peter and Jennifer of $1 billion, with subsequent annual allotments of Berkshire stock, became what the couple called “the Big Bang”—the moment they both instantly became co-presidents of one of the world’s largest private philanthropies. Based in New York City, NoVo focused its efforts on minority women, seeking to improve access to education and combating sex trafficking. They hired new staffers, many of whom were women of color, and installed as CEO a longtime philanthropic veteran named Pamela Shifman to work alongside them.

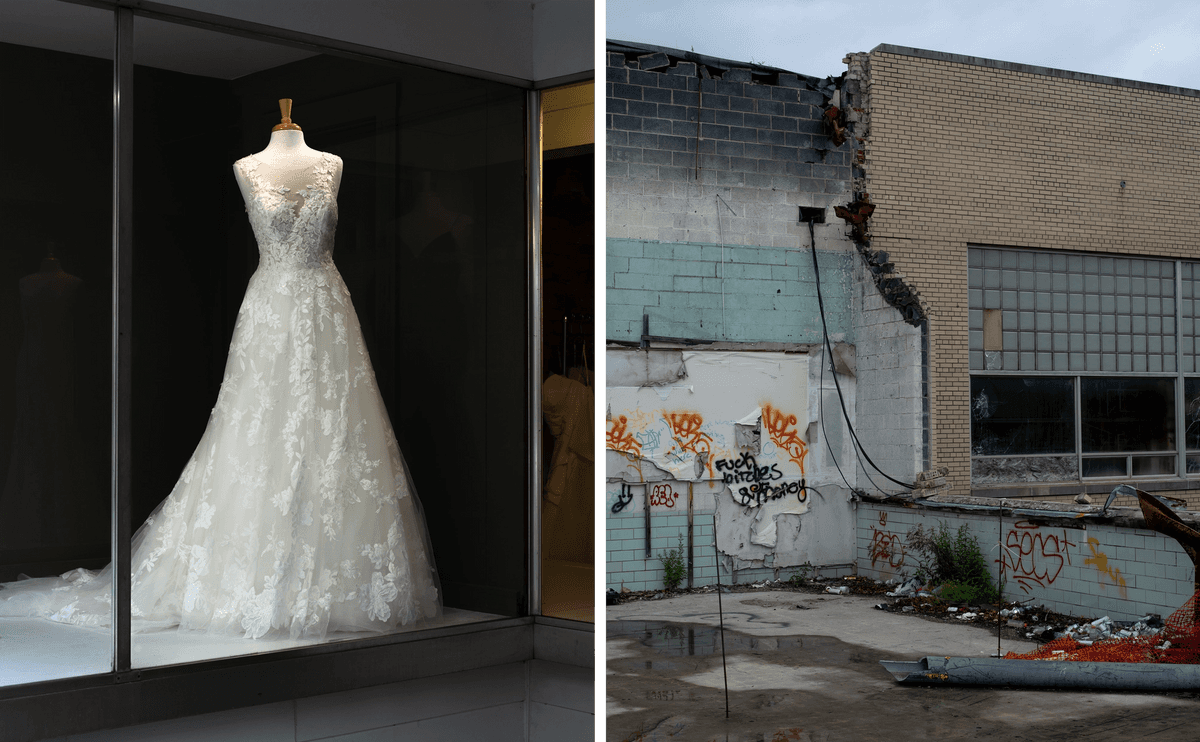

In the early 2010s, NoVo’s most visible project was the Women’s Building, a former women’s prison in Manhattan on which the Buffetts spent $25 million to convert it into an art gallery for women artists, a wellness clinic for girls, a day care facility, and a community services center. The project was hailed by New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo and feminist icon Gloria Steinem. In 2010, Barron’s included Peter and Jennifer among the world’s top 25 philanthropists.

Then, in 2019, the Women’s Building project was suddenly shut down, and Shifman left NoVo. (Shifman did not return requests for comment.) A year later, in May 2020, in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, a letter was published on the foundation’s website, which has since been taken down, announcing that, after “deep reflection” beginning as far back as the summer of 2019, NoVo “was stepping back to review our work over the past 14 years in order to determine how best to move into our next chapter.” The authors of the letter, Peter and Jennifer Buffett, added that “we understand that this may be difficult news in an already difficult time.”

The Buffetts’ philanthropic about-face was shocking, not only because it came during the most severe months of a world-historic pandemic but also because NoVo had become one of the most significant philanthropies in the women’s sector. Between just 2016 and 2018, according to data collected on the Candid database, NoVo was responsible for 37% of private funding for “all women’s rights and services for black women” and 17% of women’s rights and female-related human services in the United States.

Staff made frantic calls to grantees to tell them their programs were gone. Half of NoVo’s 36 employees were laid off. “I can’t recall a time when any foundation of their size let go of that much [staff] so abruptly, notably, mostly women of color,” an executive director of a racial equity nonprofit told a trade publication. According to one former NoVo collaborator I spoke to, laid-off staffers were required to sign nondisclosure agreements as part of their severance packages.

The sudden change of plans reverberated throughout the NoVo universe. Black Lives Matter co-founder Alicia Garza, a longtime recipient of NoVo funding, told one publication that she was getting “emotional about it because I think NoVo was one of the premier foundations working to transform power dynamics in this country,” adding that her inquiries about what was happening had gone unanswered. “The lack of transparency is not only painful, it’s jarring.”

At the time, Peter pushed back against the criticism, saying in one interview that Berkshire stock was down and NoVo shouldn’t be expected to pick up the tab for minority women’s programming indefinitely. “It’s about time other people ponied up,” he said. He also described the decision as “a divergence in the philosophy of how to get to the world we were hoping to see.”

Following the blowup, the website Inside Philanthropy gave the NoVo Foundation the award for “Trainwreck of the Year,” noting that the episode should serve at least as “a devastating reminder that even the most generous benefactors can always pull the rug out from underneath you.”

As another NoVo collaborator explained it to me, “That shift is what you get to do if you’re a billionaire. Once Peter decided he was no longer going to fund the work on behalf of women and girls—and largely Black women and girls around the country and globally, too—he just said, ‘Oops, I changed my mind!’”

It later became evident that the seemingly abrupt changes were long in the making. In 2010, Peter and Jennifer had left Manhattan and relocated to a newly acquired $1.2 million, 19th-century farm house on 50 acres of prime farm land in Kingston. There, Peter apparently had something of an epiphany.

“My work in Kingston,” Peter said on a 2019 panel, “was informed more than anything else from one event, and that was after Hurricane Irene.” While out surveying the damage around his new estate, he was struck by what the intense flooding had done to the tall, mature trees. “These seemingly intractable things—they just fell right over.” Alluding to the money NoVo would soon invest in Kingston, Peter seemed to be saying that local city and county government were the big trees, and that Novo was the hurricane. “I started to see these ingredients as the ground, literally and figuratively, and thought we can soak this not indiscriminately … and start to see where we can soak the ground and see what can fall over.” If he realized that it was a bit unsettling to liken NoVo money to a hurricane that killed more than 50 people and led to $14 billion in damages, he didn’t let on. “We’re trying to practice 21st-century alchemy,” he added. “We’re trying to turn money into love.”

All in all, it was a rather strange way to articulate a philanthropic enterprise. But as people were starting to realize, Peter Buffett was a strange man.

In the midtown neighborhood of Kingston is one of the buildings that the NoVo Foundation is currently renovating into an upgraded studio space for its media operation, Radio Kingston. The foundation purchased the local radio station for $500,000 in 2017, installing Kelly Merryman, NoVo’s COO, to oversee the station’s fiscal operations, and Peter Buffett as the chair of its board of directors. A contract deal was made with a recently formed reporting outfit called the Kingston Wire, which would produce news broadcasts for the station. The NoVo Foundation pumped $1.7 million, and then another $13 million, and then another $12 million into the radio station’s operating budget.

On a video program called “The Laura Flanders Show” (itself the recipient of $250,000 in NoVo funding in 2017), Peter described Radio Kingston as not just a radio station, but as “something else … it’s about these other ways it can put its tentacles into the community.”

The station broadcasts daily reminders about the foundation’s ongoing efforts to better the community. Often one will hear shows hosted by employees of NoVo-funded organizations interviewing the employees of other NoVo-funded organizations about the projects and campaigns they run that are funded by NoVo.

Heading south from the radio station’s new studio, I came upon the new 9,000-square-foot food co-op building, a third of which is set aside for things like office space for community project initiatives. Purchased by NoVo, the building is set to open in the next two years.

Down the block is the Hudson Valley Current, a local currency operation funded by NoVo. This is not a cryptocurrency, as some might suspect, but is in fact a new physical money designed to circulate exclusively within the new Kingston economy. The bills are roughly the size of euros, and they are gorgeous works of art, with bright, richly colored scenes of nature that feature local animals like the blue heron and the rusty patched bumblebee.

That afternoon, I looked for places where one could spend the new currency. But many of the Current-friendly businesses lacked physical locations, their proprietors likely working from home; these included dozens of services offering website design, “somatic movement therapy,” workshops on “eating well for cheap,” and “expanding consciousness & closing the gap” with the Essential Oil Wizard. There were consultants as well, many consultants, and creative writing workshops.

I can’t use it to pay my rent, I can’t do my laundry, I can’t buy clothes or food with the Current, but I can go get a massage or acupuncture. That is not actually going to save the people of Kingston.

“It’s completely useless to the vast majority of people who live and work in Kingston,” said a longtime Kingston nonprofit employee who’s received NoVo funding. “I can’t use it to pay my rent, I can’t do my laundry, I can’t buy clothes or food with the Current, but I can go get a massage or acupuncture. That is not actually going to save the people of Kingston.”

Intense poverty still persists in Kingston alongside the effects of gentrification. “You have two things at play in that neighborhood,” a former employee of a NoVo-funded entity and local resident explained to me. “One being a community dealing with incredibly impoverished, generational poverty, which interestingly for that area of Kingston is both Black and white, with a lot of interracial families. The second thing there is a very significant undocumented community, mostly Salvadoran and Honduran. The other layer to this is that you have a lot of gun violence, and in the pocket where NoVo is building and investing you see an area that’s been more policed than in any other part of Kingston. So, I’d say you have the hallmarks for successful gentrification and possibly hyper-gentrification.”

If those on the receiving end of NoVo’s transformation of Kingston have a consistent critique, it’s the lack of transparency about what exactly NoVo is up to and why—and their inability to alter the outcome. Because NoVo dispenses its funds by the tens of millions of dollars directly in the form of NoVo grants (Buffett Bucks, as some call them), along with tens of millions of dollars through several other entities like United Way, the New World Foundation, and Community Foundation, there’s no comprehensive public documentation of how much NoVo has spent in the region. NoVo does not publish an annual report, and its statements offer little insight.

“I don’t know how else to describe it, except the kind of serfdom, or this neofeudalism, when you design your kingdom and you have your blacksmith, and your farmer, and everyone gets particular tasks,” a former employee of a NoVo-funded entity told me. “It’s a reverberation of something like that, where it feels to me like people are pulling the levers of your life behind the scenes—it’s these well-resourced people on behalf of these other folks saying what you think the world needs, but you’re not allowing anyone to have their own self-determination.” As a nonprofit entity with tax exempt status, the public financial records that NoVo is legally required to file offer only a partial view that is often two or more years behind current spending. Any funding that NoVo wishes to obscure can be distributed behind the shield of a donor-advised fund. In 2019, for example, more than $15 million in donor-advised grants were disbursed by NoVo with no public disclosure of its purpose or recipient.

“I think of it as a tidal wave, the NoVo money just washes over everything here and nothing can withstand it,” one longtime NoVo collaborator and Kingston resident told me. “Just to find somebody who’s not connected to it, or supported by the foundation in some way right now, is very challenging.”

“I’m ridiculously transparent even if NoVo isn’t,” Peter wrote on Facebook in April in response to questions about the foundation’s purpose. “I’ve written songs, op-eds, articles, essays for days … [sic] podcasts, talks, on the road for over 10 years. My thoughts are pretty obvious.”

This is true. To the surprise of many in Kingston, Peter Buffett is an extremely engaged presence, at least online, where he often gets into heated debates with non-NoVo-affiliated Kingstonites. Sensitive about claims that he’s a billionaire rather than a multimillionaire (though his leadership of a billion-dollar foundation can obscure the difference), Peter also spends a great deal of time on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram, pushing back against observations that the NoVo Foundation is attempting to redesign Kingston into his own bespoke utopia.

“I’m not trying to create ‘my utopia’ and, in fact, I may just be a benevolent human being (I think ‘benevolent’ and ‘force’ can’t be used in the same sentence),” he recently wrote on Facebook.

What, then, is Peter Buffett trying to create? Some contractors who’ve worked recently for the NoVo-funded groups at the former IBM campus have been required to sign contracts with nondisclosure agreements before they begin, said one person familiar with the Tech City project. But when those collaborating with NoVo have asked for actual plans they could share, they’ve repeatedly been turned down. “How could there not be a document? Who the fuck spends $200 million without a plan?” a longtime NoVo collaborator told me.

In Peter’s own writings, performances, and interviews, however, one can perceive a patchwork ideology that appears heavily influenced by the ’60s counterculture. That Peter has made his home in Kingston, the overlooked little brother to the heady bohemian enclave of Woodstock, New York just 12 miles away, does not seem like an accident. Peter wrote an essay in 2019 on the 50th anniversary of the Woodstock music festival. “A new consciousness will not arise from some old political form whether left or right, or from a social structure named socialist, communist or capitalist,” he wrote. Rather, “it will come when we own our history, grieve for its imperfections and those it crushed, and evolve.”

For an elaborately produced music video that he financed for his own cover of the Joni Mitchell song “Woodstock,” Peter wrote about his hope for the current moment, in which he sees humanity on the precipice of going “back to our true nature built on safety and trust—in ourselves and each other.”

Peter seems equally taken with his understanding of a Native American cosmology and prophecy that places our current moment in world history at a potentially apocalyptic crossroads, between the seventh and eighth rings of fire. It was early in Peter’s relationship with Jennifer that he’d used $300,000 of his father’s money to fund his Native American theater production, Spirit: The Seventh Fire, which Peter has described as “one man’s journey to find a balance between the culture in which he exists, driven by the ‘American Dream,’ and his roots, rich in heritage, tradition and connected to the natural world.”

Peter seems equally taken with his understanding of a Native American cosmology and prophecy that places our current moment in world history at a potentially apocalyptic crossroads, between the seventh and eighth rings of fire.

By walking the correct path, Jennifer explained in an interview about the NoVo Foundation alongside her husband, society will “ignite the eighth fire, a time of peace and harmony among all people.” If society does not correct itself, however, we will soon find that the “other [path] leads to our destruction.”

It’s the looming possibility of our collective destruction that Peter often cites as the reason he’s so focused on farming and food distribution in Kingston. “A small community that is connected to itself (and its food) in as many ways as possible might make it through the coming decades,” he wrote about trying to avert our shared disaster.

Peter’s apocalyptic reasoning remains a little opaque, to say the least, possibly intentionally so. NoVo Foundation employees have suggested that the Kingston community is not yet ready to have the conversation about the foundation’s plans for their city. But a clue to Peter’s real-world goals comes from one of his most outspoken employees.

Brought to Kingston by the NoVo Foundation in 2019, the author and activist Martin Kirk has taken on a unique role across more than one NoVo-funded organization, according to several NoVo collaborators I’ve spoken to. Listed as the only other key NoVo representative on the BLUEprint proposal to redevelop the IBM campus, Kirk has also been an active presence shaping how the various Tech City organizations can help the foundation realize its goal of developing a new food distribution system.

On the NoVo-owned radio station, Kirk has held roundtable discussions with other leaders in what’s been described as the localization movement, sometimes referred to as the degrowth movement, which seeks to offer an alternative to capitalism as a way to solve the ills of climate change, poverty, and wealth inequality. Proponents of degrowth like Kirk have often courted controversy by offering theories of severe, top-down changes to how society should distribute goods as basic as food, water, and energy and by openly speculating about the capacity of average citizens to grasp what true localism would look like in action. In a debate about how best to install localism in Kingston, Kirk asked his guests recently, “Is this something that would resonate widely in the community, or is this something that you think smaller groups of people need to be deeply informed about, but everybody else doesn’t need to be?”

If some of those involved are concerned about alienating the local community by keeping them in the dark, it’s in part because the systemic changes that Kirk has written about and advocated for in the past are decidedly extreme.

Referencing the social democracies of Sweden and Finland, Kirk has written that “while these systems clearly produce more positive social outcomes than laissez-faire systems do … even the best of them don’t offer the solutions we so urgently need right now, in an era of climate change and ecological collapse.”

Kirk cites degrowth advocates and localism movement activists who are willing to break through “the dry seals of neoclassical economic theory upon which capitalism rests” in favor of new systems. “The core logic of the global operating system is going unchallenged. There are hopeful signs from the vanguard of activism, but they are tentative and vulnerable,” he’s written elsewhere. “We argue that far more attention needs to be paid to these whole-system dynamics—to the most fundamental rules of the global operating system.”

Drawing primarily on “a specific North American First Nations concept,” Kirk in a co-authored paper wrote that the global operating system suffers from a delusion that “cannibalizing the life-force of others (others in the broad sense, including animals and the Gaia life-energy of the planet) in order to amass advantage for oneself is a logical, healthy and even morally upstanding way to live.”

For those who tune into Radio Kingston, there’s a regular conversation about moving to what this post-capitalist society could potentially look like. Described as a Just Transition, the new Kingston would largely be built upon the various organizations, agricultural producers, artists, and consultancies that have been entirely or predominantly funded by the NoVo Foundation over the past five years. And now with Tech City about to serve as their primary hub, and a new printed currency in the form of the Hudson Current as the local money to drive it, Kingston is moving closer to a degrowth future, even if it’s still not at all clear what that will look like.

As Kenta Tsuda wrote in a recent essay on the degrowth movement for the New Left Review, the movement wants “humans [to] flourish to the extent that they discipline their desires and confine their actions to fulfilling ‘real’ needs, as opposed to illusory ones generated by hubris.”

In the degrowth scheme, companies would “need to be categorized as either operating in the public interest and thus allowed to continue business as usual, or socially undesirable and therefore subject to wind-down,” Tsuda wrote.

Not surprisingly, many Kingstonites I spoke with had conflicted feelings about NoVo’s investment in their city. On the one hand, the doctrines of social equity and feel-good urbanism preached by the foundation’s network of local agencies and NGOs are seen as part of an inherently superior code of social conduct. But the side effects of the Buffetts’ fashionable ideology are also hard to ignore.

“It just feels like a freight train that’s moving through Kingston,” one longtime Kingston nonprofit employee told me.

For those who’ve watched Buffett funding flood into the city’s tax-free business sector, the sheer quantity of money has led to a kind of whiplash. As that nonprofit employee explained, “Some of these organizations were either very small or didn’t exist a few years ago, and suddenly we started hearing about the budgets going from $30,000 a year to $750,000 over three years, and it’s just like, ‘Whoa! what the hell?’ Some of these organizations are great, but that’s crazy.”

It’s also not always clear why some groups are allowed onto the gravy train and others aren’t. “There’s literally no process,” one NGO employee told me. “There’s never been an open [request-for-proposal]. There’s never been guidance or criteria as to how you can get money. It’s a hand-picked process, so I don’t know what the process is for anybody else. You have to know the people, you have to be in the in-group. Other foundations, they put out RFPs, there’s a proposal that people can apply for, but here that doesn’t exist. You get asked to apply, but once you get asked, you basically have it.”

Those in Kingston who don’t align with the larger NoVo vision find themselves unable to gain much traction in a landscape that is now owned by the Buffetts. “The weird thing about Novo is they fund so many small nonprofits in the Hudson Valley that even when you have meetings with folks outside of NoVo, it’s still a NoVo meeting,” one past employee of a NoVo-funded nonprofit told me. “I’m sitting there at this project meeting with four other people and then I realized that every single person there had some relationship to NoVo money through their organization, but they were only there on behalf of their organization. And at one point I said, ‘Is this a NoVo project?’ And they were all like, ‘no no, this is just a [nonprofit group funded by NoVo]’s project,” the former employee told me. “There’s this issue in Kingston where you get involved in initiatives and you realize that the vast majority of the folks are representing organizations that are funded by NoVo.”

Given their abandonment by IBM, and given the Buffetts’ abandonment of their own previously vaunted initiatives, some Kingstonites are understandably nervous about what could happen if the Buffetts have another change of heart, while others prefer not to think about it. “They’re just willfully ignorant, so people can just keep sucking on the Buffett teet,” one current staffer of a NoVo-funded entity told me. Despite the “absolutely skeevy handling of the New York City Women’s Building, this huge scandal, everyone here wants to be blind and deaf to it.”

“The issue is that it’s not sustainable,” another collaborator told me. “Some of the nonprofits have grown in a way that if NoVo pulls out they are going to be screwed.”

But the money is so good it’s hard to turn down. At the Hudson Valley Farm Hub, the executive director, associate director, and farm manager are paid $275,000, $242,000, and $206,000, respectively. According to the most recent public financial documents, in 2019 NoVo committed at least another $47.2 million to support the Farm Hub’s operations—which would bring their total investment in the farm to over $100 million. For employees across NoVo-funded entities, staff members who once made $60,000 with modest benefits at their previous company are now making 150% more with full benefits and $5,000 a year stipends to spend on massages and other wellness services.

And since Buffett began investing tens of millions of dollars into Ulster County, gentrification has only accelerated. Some new residents are employees of NoVo-funded entities, while others simply gravitate toward small cities in close proximity to hubs like New York—places that provide amenities like local designer currencies, community-centric radio broadcasts, and farmers markets well-stocked with heirloom produce grown and cultivated by a team of farmers with master’s degrees in agriculture.

The presence of this new population is in fact crucial to the success of the projects that NoVo has set in motion here. Earlier this year, The New York Times declared Kingston the second-most desirable location in the nation according to pandemic migration patterns. The 1,500-square-foot home that went for $30,000 over its $210,000 asking price in an all-cash bidding war was soon dwarfed, according to one local businesswoman I spoke to, by the $600,000 houses being sold to buyers who toured them on FaceTime. An analysis of home prices this past April found the average sale price in Kingston was up an average of 32% from the previous year.

This was, in fact, the only issue on which I received a direct comment from Peter Buffett during the course of my reporting. Before heading to Kingston, I reached out to ask if he’d be willing to discuss the foundation’s investment in the city. He declined. “Housing and gentrification have been a concern since NoVo started working in Kingston,” he wrote to me. “The pandemic has definitely made the situation critical and I’m concerned about further attention being paid to the area, frankly.”

It all adds up to this class of people that are in this dreamlike trance. It’s like a cult, and they’re true believers. And they just want the party to keep going and going and going.

It seems to be too late for that at this point. “Peter knew that these people are just going to come in and do their creative, cool hipster thing, and then the money just flows in after them,” said one small-business owner in Kingston who’s concerned about the negative ramifications of speaking critically in public about NoVo. “The whole picture here is just the flow of the money, the propaganda from the radio station, the mystification of where power resides, it all adds up to this class of people that are in this dreamlike trance. It’s like a cult, and they’re true believers. And they just want the party to keep going and going and going.”

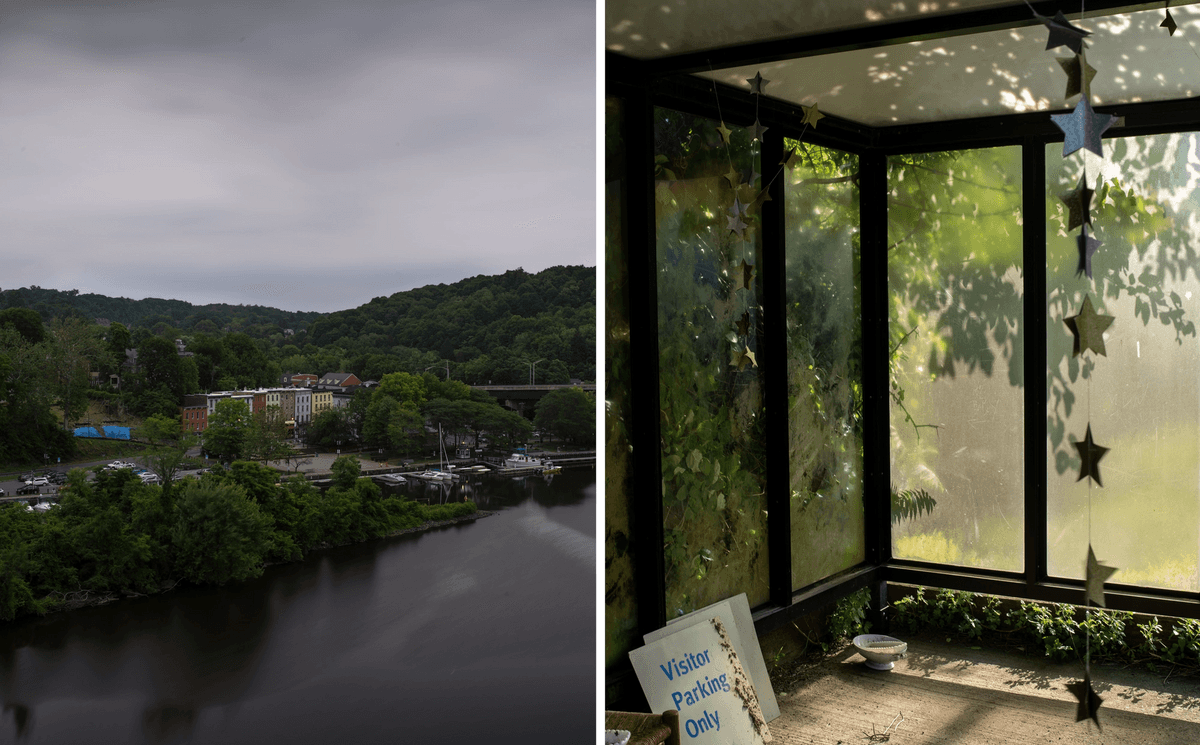

On the Saturday morning before I left Kingston, I headed downtown, walking east on the steep hill where most of the restaurants and coffee shops managed to survive the pandemic—thanks, in part, to the influx of new residents with disposable income. The hill stops at the docks along the Hudson River. It was here that Kingston first emerged, in the 1820s, as a river port trafficking coal from the mines of western Pennsylvania. Soon, Kingston began exporting its own natural resources, loading up ships with Catskill bluestone, a firm, attractive rock that became the roads and sidewalks for a nation turning its farmland into new cities.

Walking the water’s edge, I came upon the Appolonia, a 64-foot sailboat about to set out with 12,000 pounds of locally produced grain, hot sauce, and spices destined for boutique shops and restaurants in New York City. The young woman in the hull is busy with final preparations for the trip she says might take four or five days, depending on wind conditions. In Brooklyn, the four-person crew will pick up single origin coffee beans and other sustainable New York products for the return to Kingston. To strengthen the green supply chain, the ship’s mates will complete the distribution by moving hundreds of pounds of goods around Kingston with an e-bike and trailer.

Walking back uptown for the weekly farmers market, I saw two Audis and a gray Porsche Cayenne near the entrance, luxury vehicles that suddenly looked less luxurious as a gorgeous cherry red Ferrari rolled through the intersection. Inside the market, a guitarist sang indie rock cover songs for dancing toddlers. The lion’s mane mushrooms were locally foraged, the bluepoint oysters beckoned from their tubs of ice. One woman strolled past holding a head of fresh lettuce with both hands. There were $18 bottles of ready-to-drink cocktails sold by a local distiller, whose Gin Basil Crush was “curated and bottled in the Hudson Valley.”

A tent of nurses from Health Alliance, the local hospital, were collecting signatures to fight to reopen their rehab and detox center that had been shut down to save costs during the pandemic. “Opiates and fentanyl are big time,” one nurse said to me.

According to New York state’s most recent annual report, Ulster was the second-highest county for hospital discharges due to opioid use statewide, ahead of the Bronx. Kingston’s poorer residents are falling through the cracks because of lack of funding. For example, over the past year, the owners of Chiz’s House, a boarding home in Kingston for as many as 60 residents, many suffering from schizophrenia, had tried to find a new owner willing to buy the building and let the tenants stay. But no one would purchase the place on those terms because the property has too much potential value without the tenants. Various advocacy groups in Kingston fought for either Ulster County or the NoVo Foundation to purchase the building and convert the group home into a fully funded nonprofit, just as NoVo had done with other organizations across the city.

“I spoke to Peter,” a daughter of a Chiz’s House tenant wrote on Facebook about her attempts to save her mother’s group home. She says she asked him if he could help, but he told her, “the fact is, NoVo tries to build self-sufficient programs,” and Chiz’s was better suited to be fixed by the local government.

The building was finally sold in May and the tenants were evicted. Another group home, The Bridges, was also recently sold, leaving its disabled residents without a place to live. “Why not put something into helping some people who are actually desperately and urgently in need of help right now? People that nobody else was going to help?” a Kingston nonprofit employee who’s received NoVo funding told me. “Instead of spending hundreds of thousands of dollars on an artwork currency, why not save Chiz’s House and all these people who are now homeless?”

“I am coming to terms with how much power I have. This is new to me,” Peter wrote recently in a social media post. “Especially when so many have become dependent on NoVo’s resources. We have a responsibility and we will try to meet it. And probably be imperfect about it.”

I walked toward the exit of the farmers market, the sun warm, the air filled with music. All around me, people smiled and laughed, some gathering socially for the first time since lockdowns. There are two Kingstons, the old and the new, and they’re both changing. Peter Buffett’s NoVo Foundation has a plan, but nobody knows exactly what it is. And that too is part of the plan.

“I joke about it, that we’re trying to use money as if money doesn’t matter,” he once said. “But that’s the trick, you have to use the existing structure so that the existing structure can go away.”