How China Is ‘Sino-Forming’ the Planet

David Goldman’s new book rings an urgent alarm on China’s plans for global takeover but misses the communist regime’s vulnerability

Our era now has its Paul Revere.

David P. Goldman in his new book, You Will Be Assimilated: China’s Plan to Sino-Form the World, delivers stark warnings to America—and by implication the wider international community—about the Chinese regime. That regime, he shows us in page after page, has grand ambitions. In his telling, China is on the verge of achieving them and in the process subordinating other nations. Goldman sees China as a giant, soon to dominate the world unless the United States takes drastic measures. He is concerned “because America’s response to China’s global ambitions is a failure.”

There are two reasons for this failure: First, Americans have “chronically” underestimated the Chinese regime. He correctly points out that our adversary is not “moth-eaten Marxism.” It is “a 5,000-year-old empire that is pragmatic, curious, adaptive—and hungry.” We are not competing against “drunken and corrupt Soviet bureaucrats.” We’re facing a “Mandarin elite, cherry-picked from the brightest university graduates of the world’s largest country.” The Chinese, Goldman believes, already have an economy, as measured by purchasing power parity, around $4 trillion larger than America’s, and they are busy adopting plans, such as the Made in China 2025 and Belt and Road initiatives, that will make it even bigger and more technologically advanced.

Second, America’s response is failing because Americans have yet to address their own problems. The federal government has lost its will and capacity for leading grand projects in the national interest. It no longer sets big goals and devotes resources to research and development. As a result, China “is overtaking the U.S. in key technologies” and is far ahead in some crucial ones like 5G communications infrastructure. How could it not surpass America? The Chinese state now graduates six times more scientists and engineers than the United States. “China is dangerous,” Goldman writes, “because it’s adopted the American idea of a science driver for growth.” Moreover, China is investing in infrastructure, and the United States is not. American airports, roads, and rail lines are decades out of date and give the U.S. the feel of a Third World society compared to modern China.

The trend lines are clear. “America is on track to become poor, dependent, and vulnerable—unless we revive the American genius for innovation,” Goldman warns.

Is this gloomy prediction right?

Throughout You Will Be Assimilated, Goldman urges America’s leadership to assume the worst and plan for a future in which Xi Jinping, China’s audacious ruler, succeeds in willing Chinese society to greatness. Xi speaks of “the Chinese Dream” and of “the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation” and has taken his regime far. Americans and others should act as if Xi will continue to achieve success. Therefore, nobody should assume, as some do, that the Chinese communist state will fail. China, after all, has not “collapsed.” Goldman, I should note in the interests of full disclosure, severely criticizes my prediction that it would. Yet on this point I agree with him: Waiting for the Chinese state to defeat itself is not wise. Goldman’s main thesis, that America must recognize China’s technological success and act fast to meet it, is correct.

In support of his extrapolative thesis, Goldman argues that China’s story is one of continuity, bolstering the narrative now propagated by Xi and the Communist Party that the current-day regime is like prior Chinese empires. “China,” Goldman writes in service of that proposition, “has been ruled by an emperor for thousands of years, and the present dynasty—ruled by a committee of bureaucrats, rather than a flesh-and-blood royal family—is an updated version of the imperial system that has revived itself again and again throughout the millennia.”

There are some continuities in China’s long history of course. It is true, for example, that today the country is increasingly totalitarian just as it was totalitarianlike during the two millennia of imperial rule. Yet the current regime is also fundamentally different in important ways—and far more dangerous—than the imperial-era ones. It is true, for instance, that China’s emperors maintained they were the world’s only legitimate rulers. They clung to the belief they had the Mandate of Heaven over tianxia, meaning “All Under Heaven,” and so all other peoples owed them cooperation, goodwill, respect, and obedience.

In reality, however, Chinese emperors did not attempt to impose their rule over the world. China was not, as the popular belief holds, the world’s sole superpower. China’s geliguojia—“separated country”—system meant that Chinese emperors, as Arthur Waldron of the University of Pennsylvania points out, “avoided contact lest that lead to disorder.” They were among the staunchest anti-globalists of their time. A Ming Dynasty emperor in the early 16th century even destroyed China’s own 3,500-ship “Treasure Fleet,” the world’s strongest navy of the time, to enforce self-isolation.

The world would be a safer place if Chinese rulers still acted that way. Now, however, Xi Jinping has built the world’s largest navy and speaks in favor of globalization to foreign audiences. Yet instead of being comforted by that talk, as many non-Chinese are, they should be alarmed, especially because Xi is serious about promoting tianxia.

“Tianxia is a long Chinese political tradition of practice and ideal that is being revitalized and reenergized in today’s People’s Republic,” Fei-Ling Wang, author of The China Order: Centralia, World Empire, and the Nature of Chinese Power, told me last year. “The Chinese dream of tianxia, or the China Order, assumes a hierarchical world empire system.”

China, of course, is at the top of that hierarchical system, so it is ominous that Xi has been recycling tianxia themes this century. Recently, his references have become explicit. “The Chinese have always held that the world is united and all under heaven are one family,” he declared in his 2017 New Year’s Message.

If this were not clear enough, in September 2017, Foreign Minister Wang Yi made sure Xi’s audacious message was understood, at least inside the regime itself. Wang wrote in Study Times, the influential Central Party School newspaper, that “Xi Jinping thought on diplomacy”—a “thought” in party lingo is an important body of ideology—“has made innovations on and transcended the traditional Western theories of international relations for the past 300 years.”

Wang’s reference to 300 years is pointing to the Treaty of Westphalia of 1648, which established the current international order. The pact recognized states as sovereign, so Wang’s use of “transcended” suggests Xi wants a world without sovereign states, undoubtedly a unified world ruled by him. When Chinese leaders talk of a “community of common destiny”—sometimes called a “community of shared future for mankind”—they mean the common obligation of subservience to China’s ruler.

What could be the most dangerous combination of beliefs today? China’s tianxia and Chinese territorial aggression.

“Since 800 A.D., the Chinese borders have stayed the same,” Goldman said in an interview with a Swiss publication, reprinted at the end of You Will Be Assimilated. “I don’t see any intention to expand—apart from the South China Sea.” In 800 A.D., China was less than half the size it is today. More important, China currently has territorial ambitions well beyond the South China Sea. It claims sovereignty over the Japanese-administered Senkaku Islands in the East China Sea and large portions of India. Moreover, Xi’s Beijing is now laying the basis for claims on portions of Tajikistan, to Japan’s Ryukyu chain in the East China Sea, and over a wide expanse of the Russian Far East including Vladivostok. China is trying to dismember its neighbors and close off its peripheral waters—in other words, the global commons. So Goldman’s statement is way off base.

Yet to his credit he sees China as now going after more than land and water. It is going after everything. “They want to have everybody in the world pay rent to the Chinese Empire,” Goldman said in the same interview. “They want to control the key technologies, the finance and the logistics, and make everyone dependent on them. Basically, make everyone else a tenant farmer.”

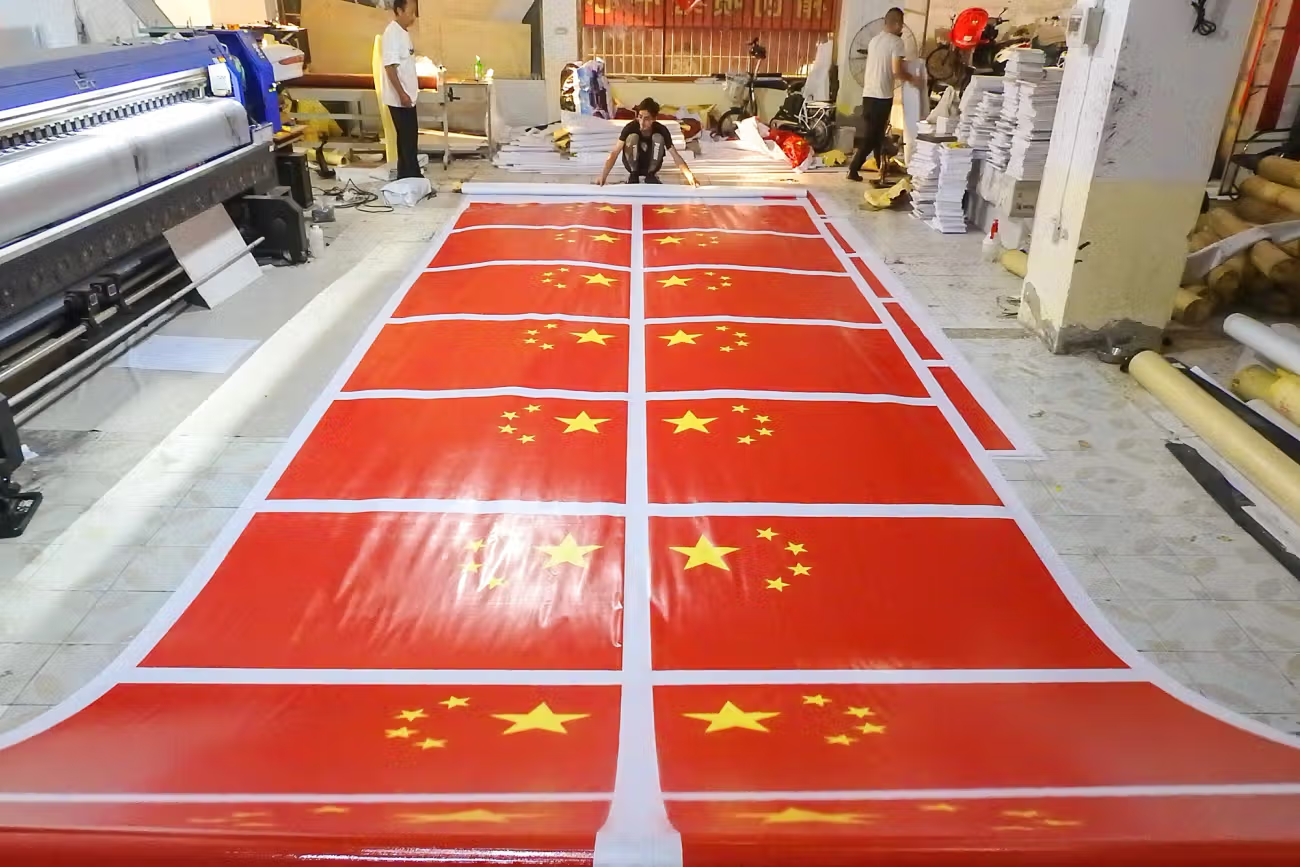

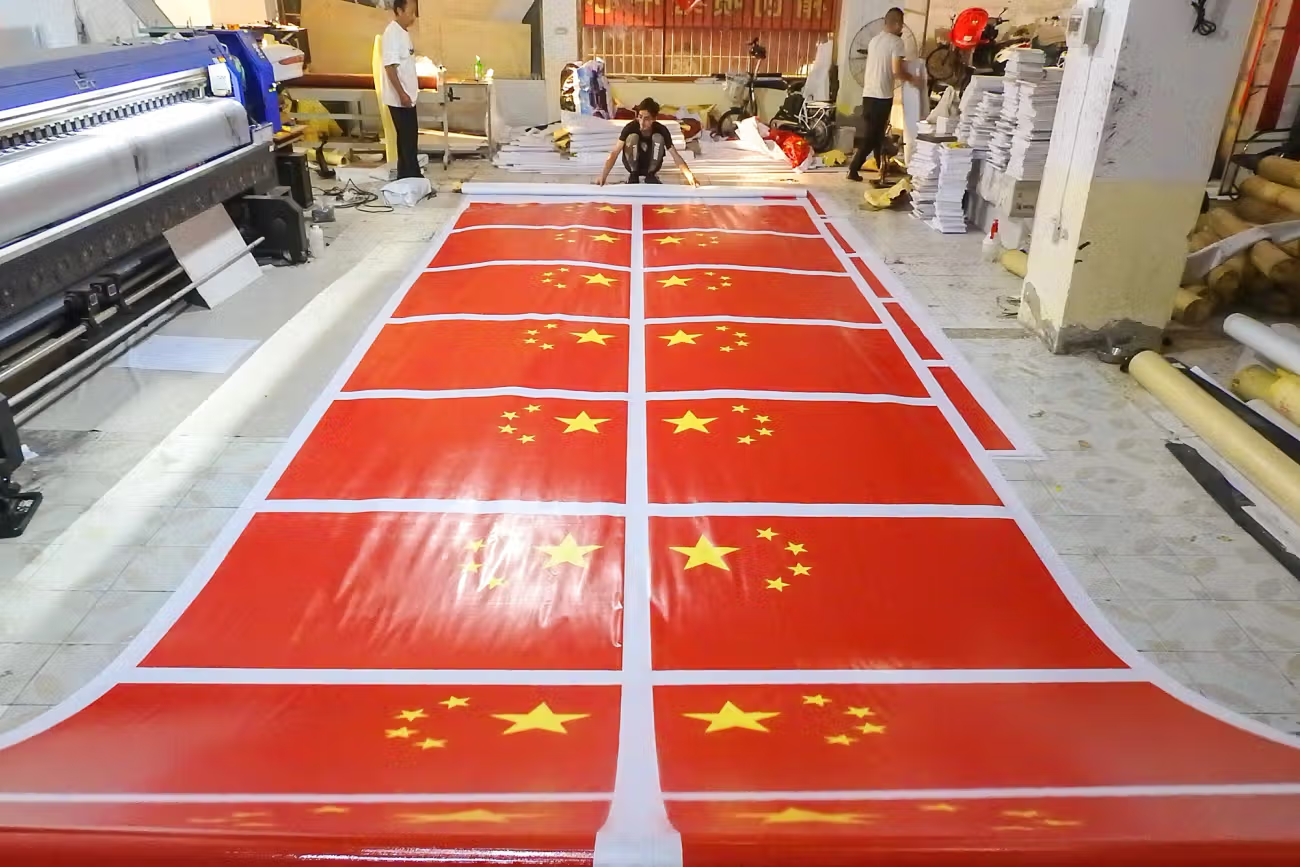

As we learn toward the end of the book, Fudan University’s Wen Yang believes China “has evolved a superior mode of social organization, and that it is prepared to ‘redefine the world.’” Goldman puts this menacing thought slightly differently, playing off his subtitle: “As China continues to transform itself, it has begun the Sino-forming of the rest of the world.” In Goldman’s telling, China is moving to assimilate us, “like the Borg in Star Trek,” a pop culture reference that both explains the regime’s ambitions and terrifies readers.

He terrifies too much, however. China does not have infinite resources, and we could already be witnessing “Peak China.” The official Xinhua News Agency in January ran a piece titled, “Xi Stresses Racing Against Time to Reach Chinese Dream,” a clear indication Communist Party leaders are worried that time is running out for their regime. It’s not hard to see why they are worried. China’s demography is in the first stages of accelerated decline, China’s environment is exhausted—think scarcity of water despite the recent flooding—China’s people are increasingly restive, China’s leaders are losing support around the world, China’s economy is still having difficulty recovering from COVID-19.

And the United States, which for five decades supported Communist Party rule, has now ditched generous “engagement” policies and begun to challenge Beijing. Goldman, unfortunately, did not notice this momentous change. Moreover, he exaggerates Chinese capabilities. For instance, Goldman is in awe of Huawei Technologies, China’s “national champion” maker of telecom-networking equipment and smartphones, currently leading the world in both lines of business. “Huawei achieved self-sufficiency in chip production and continues to expand with Chinese and other Asian components,” the author warns. “Former House Speaker Newt Gingrich deplored this outcome as ‘the greatest strategic disaster in U.S. history.’”

Perhaps. But as fearsome as Huawei appears, the company is not yet self-sufficient in semiconductors. Huawei’s Habo Investments subsidiary has gone into the business of making semiconductors, but it will take years for it to be able to manufacture the sophisticated chipsets needed to make its products competitive.

In the meantime, Huawei, featured prominently in You Will Be Assimilated, will be scrounging the world for semiconductors. In May of last year, the U.S. Commerce Department added Huawei to its Entity List, which means American companies were required to obtain licenses before they could sell or license the company products and technology covered by the U.S. Export Administration Regulations. The effect of the designation was deferred by a succession of waivers, but the Trump administration has since gotten serious and stopped the flow of, among other things, chips. Additionally, to make matters worse for Huawei, Commerce has tightened rules. Now, even foreign businesses require licenses before selling to Huawei chips made with U.S. equipment. The result is panic in Shenzhen, Huawei’s home base, and undoubtedly in Beijing as well. The American rules are so comprehensive that even Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corp., China’s largest chip foundry, was forced to stop supplying Huawei.

As a result, Huawei will exhaust its chip supply for phones, now its main product line, sometime by the middle of next year. The chip shortage for Huawei’s other line of products—5G networking kit—is not as severe according to industry estimates, but the company could run out before Chinese fabricators can begin producing chips. Beijing is of course “hell-bent” on developing its own semiconductor industry, as Claude Barfield of the American Enterprise Institute points out, but success in doing so is by no means assured.

“Trade wars and tech boycotts have failed to slow China’s plans,” Goldman’s book tells us, but this assessment, as we can see from Huawei’s predicament, is just plain wrong. The contest is not over, of course. Beijing will, one way or another, try to come to Huawei’s rescue because as goes Huawei so goes China’s tech ambitions. Yet we can see that America’s path to success must go beyond inward-directed projects to strengthen the homeland. The United States, as Trump demonstrated this year, can reach out and shake China’s regime.

The legitimacy of the Chinese Communist Party depends on the continual delivery of prosperity and the aura of China’s success around the world, but Xi Jinping’s bold ambitions have pushed the regime to the limits—and perhaps beyond those limits—of what it can accomplish. Huawei’s predicament shows that Xi’s plan to take on the world is not guaranteed to be successful.

So let us heed Goldman’s warnings, but let us also recognize the areas of China’s fragility and its many weaknesses. The Chinese may want to assimilate, Sino-form, or dominate us, but we can make sure they do not have the means to accomplish any of that.

Gordon G. Chang is the author of The Coming Collapse of China. Follow him on Twitter @GordonGChang.