Code Pink’s Next Battle

Can the women’s antiwar group, active in the anti-Israel BDS effort, turn people against drone warfare?

“Jeremy, is President Obama a serial murderer?” Ralph Nader asked.

Nader directed this question to Jeremy Scahill, the journalist for The Nation who’s been working on a documentary about targeted killing, at Mount Vernon Place United Methodist church in Washington D.C., on a recent Saturday night. Scahill had just finished delivering a blistering 40-minute speech attacking Obama’s foreign policy, which he said doesn’t differ in any significant way from George W. Bush’s and, in fact, has only expanded on some of its worst aspects. Nader stood in front of his seat, waiting expectantly for Scahill’s response.

Scahill hedged for a minute before offering his answer: “It comes with the office title.”

Scahill’s remark—and Nader’s question—typified the outrage at what was arguably the world’s first Drone Summit. Held on April 28 and 29 in Washington, D.C., the event was sponsored by Code Pink, the Center for Constitutional Rights, and the British legal organization Reprieve, which lobbies against the death penalty and represents inmates at Guantanamo Bay. Scahill—who received a boisterous standing ovation from the crowd—had unleashed a fusillade of zingers in his speech, including: “President Obama is the one operating secret death panels”; “We have set an agenda that terrorists need to die. And we have some hammers, so let’s go find some nails”; and: “We have become a nation of assassins.”

Those gathered at the conference count themselves among a lonely minority, for the program, perhaps the country’s worst-kept secret, is actually immensely popular among the American public. In a February Washington Post/ABC News poll, 83 percent of respondents approved of the U.S. drone program; 63 percent approved of using drones to kill suspected American terrorists overseas. That may not be a surprise, given that drones are credited with breaking the back of al-Qaida in Pakistan. But critics of drone warfare, including the 250 participants at last week’s conference, contend that the U.S. program is illegal, a boon to jihadist recruitment, a violation of Pakistani sovereignty, and far less precise than the U.S. government claims, particularly with the use of “signature strikes,” in which targets are plucked out based on a “pattern of life.” (The methodology behind signature strikes remains secret, but it is believed to involve tracking movements, looking for the transport of weapons, and building a dossier of other incriminating behavior.)

The Bureau of Investigative Journalism, which participated in the conference, claims that at least 2,429 people have been killed in CIA drone strikes in Pakistan since 2004, and that at least 479 of them were civilians. But with drones now finding their way stateside—the Border Patrol uses unarmed Predators at both borders, and the Federal Aviation Administration has begun drawing up rules for domestic drone use by law enforcement and private operators—anti-drone activists believe that the public can be turned against drones, especially if they believe that their own privacy and civil liberties are at risk.

Which is why, though drone warfare appears entrenched as a counter-terrorism strategy, Code Pink hopes that it’s not too late to raise the alarm about growing domestic drone use, which may, in turn, raise concern about secret wars and civilian casualties overseas. The conference was the brainchild of Code Pink co-founder Medea Benjamin, who is also the author of a new book on the subject, Drone Warfare: Killing by Remote Control. Benjamin, along with the event’s co-sponsors, aims to catalyze a nascent anti-drone campaign that includes constitutional scholars, aging Vietnam War activists, Pakistani lawyers, Yemeni journalists, and Occupy protesters concerned about domestic surveillance.

“Unless we shine a light on it, we’re going to turn around and say, ‘Wait, how’d we get involved in all these wars without knowing about it?’ ” Benjamin told me. “We’re going to turn around and say: ‘How do we suddenly have drones watching us here at home without us knowing about it?’ I think this is a movement in some ways behind its time when it comes to the use of drones for lethal killing and ahead of its time when it comes to drones for spying here at home.”

***

Here’s what that guild of doves is up against: powerful military contractors, the intelligence community, a 55-member Congressional Unmanned Systems Caucus, and the president himself. Benjamin’s campaign also comes at a nadir for the antiwar left. The election of Barack Obama sapped the energy from her organization, which had thrived as much on theatrical gestures of pique toward George W. Bush as it did on opposition to that administration’s wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

“Code Pink is much smaller than we were during the Bush years,” Benjamin admitted. “We find that though the core members of Code Pink are just as angry at Obama as we were at Bush, a lot of the people who supported Code Pink became quiet when Obama got elected.” (In its 2010 IRS filing, the organization reported $317,380 in assets—or about 7 percent of the cost of one Predator drone.)

But Benjamin and her fellow activists see an opportunity in the momentum of the still inchoate Occupy movement—and view drones as a way to capitalize on activists’ frustration with U.S. militarism. They hope to harness Occupy’s energy and organizational skills, as well as its popularity with young people, and in turn to teach Occupiers how the use of drones here and abroad is, in fact, related to their economic concerns. Anti-drone activists draw a connection between outsized military spending and drone warfare, which they believe provides a convenient and low-risk method of perpetuating existing conflicts while encouraging the military and CIA to expand or open new, costly campaigns in places like Yemen and Somalia. What’s more, they argue, drones could soon be deployed by police departments to monitor protesters and even to shoot them with nonlethal weapons. They predict that communities will be under perpetual surveillance, spied upon by drones equipped with powerful cameras and facial-recognition technology. (Drone manufacturers have begun vigorously marketing their products to U.S. police departments, several of which already own drones.)

While Code Pink is known for flamboyant displays like holding “kiss-ins” outside of recruiting centers (“Make out, not war!” their signs read), Benjamin doesn’t seem interested in coloring this campaign pink. (Her book, though, was on prominent display at the conference.) It may be something she’s learned from Occupy’s leaderless structure or is simply an unfortunate exigency of an attenuated antiwar movement.

“Now we have the Occupy movement, so it doesn’t have to be Code Pink,” Benjamin said. “It feels really good when you know that some war criminal is coming to town and you can call up folks in the Occupy movement and they’ll be out there. Or we can join in their actions, for example, on holding the banks accountable.”

Benjamin, who moved a couple years ago from San Francisco to Washington, D.C., has taken part in a number of Occupy actions and speaks glowingly about its mission, and it’s clear that it’s helped to reanimate her organization. But Occupy isn’t the only protest movement that Code Pink hopes to harness. In our interview, Benjamin emphasized that drone opponents could learn something from their peers engaged in BDS—the boycott, divestment, and sanctions aimed at Israel.

“This is an opportunity to make links with the Israeli peace movement, with the Palestinian social justice movement, to use some of the strategies by the BDS to look at getting divestment from drone industries here at home, getting students involved and seeing what drone research is being done on their campuses, and trying to separate their campuses from the development of drones,” she told me. “So, I think there’s a lot of overlap and a lot of lessons that we can learn from the BDS movement.”

In my conversations with anti-drone activists, it quickly became clear that they consider the BDS campaign an important model for their work, despite its lack of tangible successes. The two causes have much in common. Both can draw on narratives of powerful militaries subjugating disempowered Muslim populations. And with Israel having essentially invented the modern military drone, as well as being the No. 1 exporter of drones, the links are more than thematic. Israel pioneered targeted killing by drones and now deploys them extensively in Gaza. The Predator drone—the most recognizable and popular umanned aerial vehicle in the American arsenal—is based on an earlier design by Abraham Karem, an Israeli. For many activists, then, drones are another arena in which the United States and Israel are deeply connected—and deserving of censure. These close military partners, activists argue, both rely on similar technology to break international law.

***

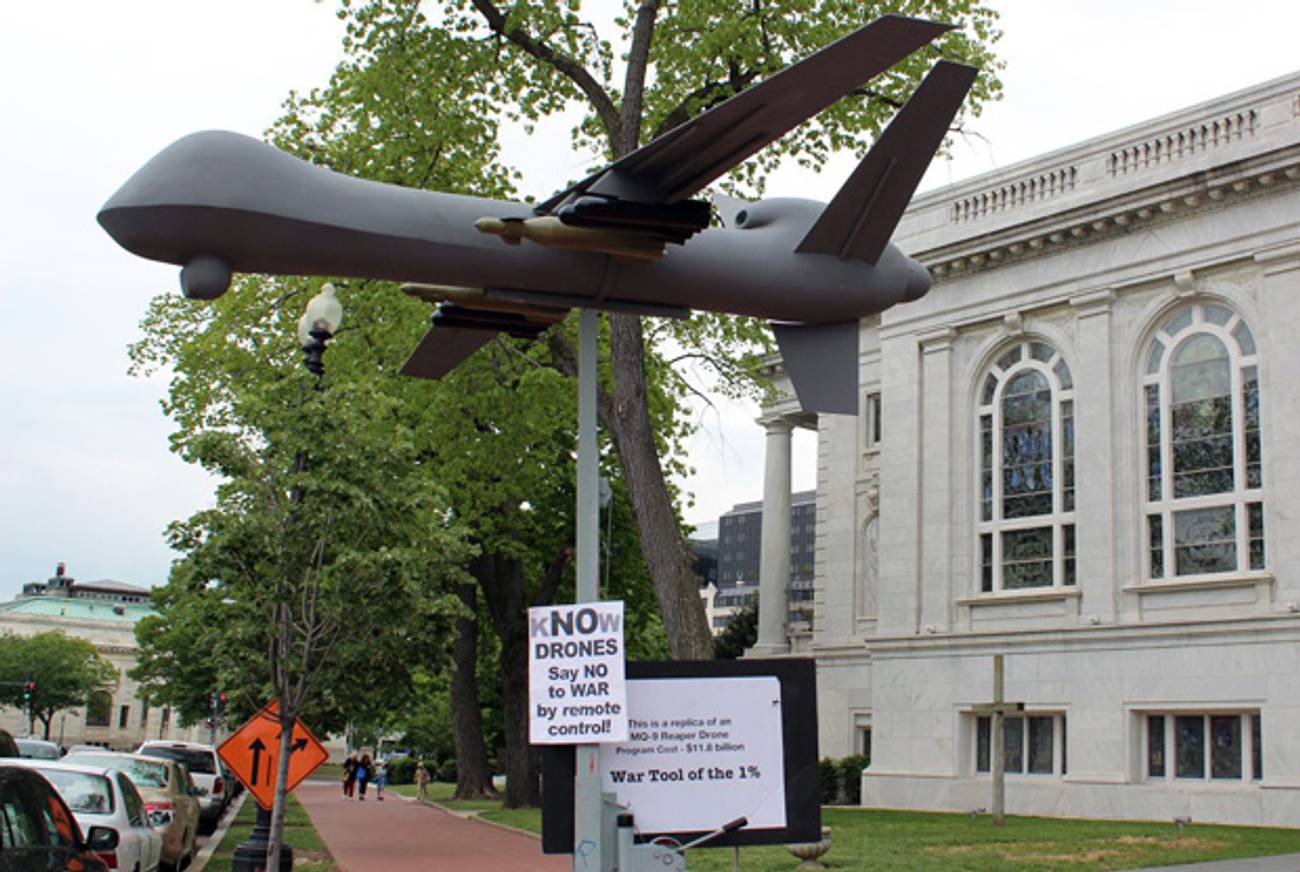

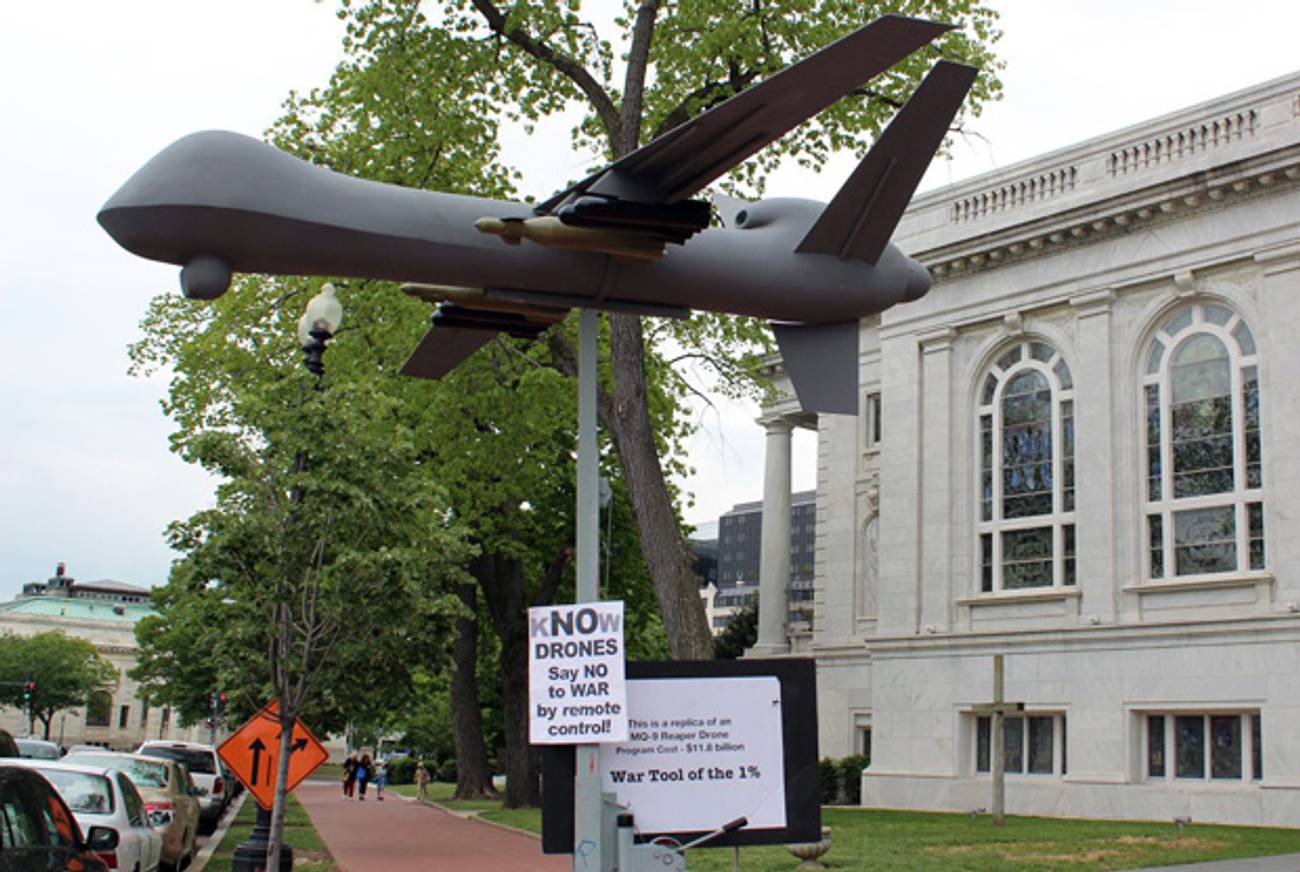

Allegiances at the drone summit were declared by way of T-shirts, pins, and free pamphlets. One summit volunteer wore a T-shirt in support of Mohammad Mossadegh. Veterans for Peace garb was ubiquitous; BDS or Gaza Flotilla gear popped up periodically. A couple men wore black shirts bearing the pleading but tongue-in-cheek text, “unarmed civilian.” (They’re part of an organization called Know Drones, which tours the country with drone models and educational materials as a way of stirring up anti-drone activism.)

The archetypal summit attendee was Jimmy Johnson, a 34-year-old Midwesterner. Wearing faded blue overalls and standing well over 6 feet tall, with a small paunch, scruffy cheeks, and a buzzed head, Johnson at first has the look of a farmer far from home. But his tattoos give him away: Across one set of knuckles is the word shalom; tzedek decorates the other hand. And in a curved line on his back, just below his neck, are the words “tzedek, tzedek tirdof lemaan tichyeh.” (Justice, justice you shall pursue so that you may live, a verse from Deuteronomy.)

Johnson, who is Jewish, is a one-man advocacy organization, operating under the name Neged Neshek, meaning “Against Arms.” He researches and tracks Israeli weapons development and the export of these technologies. “In a way you’re kind of following the Occupation out into the world,” he told me.

Johnson lives in Detroit, where he also grew up. In the 1990s, he served in the Army as part of a fuel-hauling unit working in support of the No-Fly Zone in northern Iraq. “It was planes that were going back and forth and bombing once, twice a week for the whole decade,” he said. “That was my role.”

After a year-and-a-half, he deserted, earning himself a dishonorable discharge. I asked him why he left: “Maybe I got a little conscious of activism and then I forgot why I was helping to kill Iraqis. It didn’t make any sense to me.”

A relationship later took him to Israel. He wasn’t a Zionist then, he said, and isn’t one now. But he remained in Israel for 10 years and became disturbed by the demolition of Palestinian homes.

Two years ago, he moved back to Detroit to take care of his brother, who would soon die of an illness. Johnson is trained as a mechanic, but the city has few jobs, so he’s devoted to his work with Neged Neshek, which in turn has brought him into contact with a number of European and Israeli groups concerned with the arms trade and Palestinian rights. He’s also active in the Detroit Occupy movement, and he’s the author of an unpublished 47-page pamphlet, “Fragments of the Pacification Industry: Exporting the Tools of Inequality Management From Palestine/Israel.”

Whatever one might think of his beliefs, Johnson is, like many of those I encountered at the drone summit, deeply versed in the issues. He participated in a panel at the summit (“Ethical/Political Issues of Drone Use & Targeted Killings”) and gave a brief presentation about Israeli drones, where he called the 1982 Israeli invasion of Lebanon “a turning point” for the technology.

Johnson is also, like many other attendees, essentially a lone operator while also being a relentless networker. I spotted him speaking with panelists and activists throughout the weekend, often waiting patiently nearby as a scientist or lawyer packed up his presentation materials. In some ways, the structure of this young movement mirrors the drone program itself, which is dispersed among dozens of military bases around the United States and sites abroad and is supplied by military contractors throughout the country. It is a distributed network relying on close communication and sharing of data.

***

On the second day of the conference, attendance had slipped from the first day, but energy levels were high. That morning, a CIA drone had struck in Miramshah, a frequent target in North Waziristan, a district in Pakistan’s FATA region. I sat in on a discussion group of a dozen or so activists, and on a whiteboard someone had written the town’s name, underlined it, and drawn an arrow pointing to text that read, “4 girls killed this a.m. by CIA drone strikes / BOO! HISS!!” (News reports said that four unnamed militants were killed. They were apparently holed up in an abandoned girls school.)

One group was focused on domestic drones; another, which included a group of Stanford law students, was discussing legal policy. Mine was tasked with brainstorming direct action, education, and organizational strategies. The conversation was free-flowing and generally cordial but suffused with the antic passions endemic to political meetings. Activists took turns speaking and sometimes fluttered their fingers in the air to show agreement.

There was wide support among the group for the use of dramatic visual aids and of gory imagery. One man proposed distributing stickers with graphic photos after drone strikes. “That way they have to confront it,” he said. Another suggested using mural art to depict events in Afghanistan. “We want people to know what it looks like,” said a man from Know Drones, the touring educational organization, who identified himself simply as Jeff.

A man with a Veterans for Peace shirt and pin, his thin white hair matched by a white beard, worried that base protests, while a popular idea, weren’t that useful. “The thing is you’re not educating anybody,” he noted.

Another Veterans for Peace man, this one in a Free Bradley Manning shirt, said, “Don’t forget economics”—that is, emphasizing the cost of the drone program. (A Reaper drone, for example, costs about $30 million of taxpayer money, and Hellfire missiles go for about $70,000 each.)

The man launched into a short disquisition on his background. He almost became a Catholic monk but now attends a synagogue, he told us, before name-checking Rabbi Michael Lerner, a Bay Area-based rabbi known for his social activism.

A National Day Against Drones was discussed several times before the group agreed that it was one of their most promising ideas. When someone raised the issue of protesting other weapons systems, like cruise missiles and AC-130 gunships, both of which have been used to strike militants in Somalia, a man emphasized the particular visual power of drones: “This is our new image. It’s a good image that we can use.”

A middle-aged, dreadlocked man, wearing sunglasses and sitting outside the circle, offered a slight critique. “I’m still not focused on what the endgame is,” he said. “At the end of the day, what needs to be done so that everybody can go home?”

After a few seconds, someone else spoke up, returning to an old standby: “Right now, I think a really good model is the BDS movement.” He emphasized that it has a “specific ask”—i.e., boycott Israel—and that the anti-drone movement should as well.

A woman who identified herself as Barbara Wien, an academic involved in the Peace & Justice Studies Association, added, “Israel is the largest exporter of drones, so that’s a connection between our anti-drones [campaign] and BDS work.”

“How many people are on Facebook?”

Some hands went up.

“So is the government,” a woman said, sourly.

A man in a cutoff T-shirt proposed that Columbia’s journalism school “would be a great place to do some street theater, before they all become flunkies for AP and UPI.”

The Lockheed Martin union was mentioned as problematic (too in thrall to management), but Lockheed, which manufactures the Hellfire missile and is the country’s largest military contractor, was named as an important protest target.

Jeff returned to the notion of reaching out to interfaith groups, before an elderly woman, whose black T-shirt read “We Will Not Be Silent” in Arabic, Hebrew, and English, remarked that she doesn’t like the use of the word “terrorism,” even in regard to Pakistani Taliban attacks on Pakistani civilians. “We have no business being there or telling people what to do,” she said. Another woman had trouble with “acknowledging that there’s even a problem with terror,” saying it feeds into militarism.

Later, the groups reconvened to share what they’d settled on. The group I observed agreed on distributing educational materials, using public art and street theater, and organizing a National Day Against Drones. A statement was read aloud; some slight amendments were suggested and ratified, including one, put forth by a roboticist, noting that certain nonmilitary uses of drones are acceptable.

Medea Benjamin, standing in front of a blowup of her book cover, raised the possibility of leading a delegation to Pakistan to meet with activists, lawmakers, and victims’ families. She asked Shahzad Akbar, a Pakistani lawyer, if they would be welcomed in his country.

“Yes, yes. We have plenty of jail cells,” he cracked.

***

The day after the summit ended, John Brennan, the president’s chief counterterrorism adviser, gave a speech defending the drone war. It was a rare on-the-record comment about the secretive program, though it offered no revelations about targeting procedures or other such matters. Speaking at the Woodrow Wilson International Center, Brennan was interrupted by a protester, who yelled at him about the deaths of innocent people and the sanctity of the Constitution. Few people in that room likely knew that the woman disrupting Brennan was Medea Benjamin. The woman whose group had been the colorful vanguard of antiwar protest under the Bush Administration went unrecognized. ABC News reported that “a well-dressed blonde woman” had to be carried out of the auditorium.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Jacob Silverman is a Brooklyn-based freelance writer and book critic. He is also a contributing editor for the Virginia Quarterly Review.

Jacob Silverman is a Brooklyn-based freelance writer and book critic. He is also a contributing editor for the Virginia Quarterly Review.