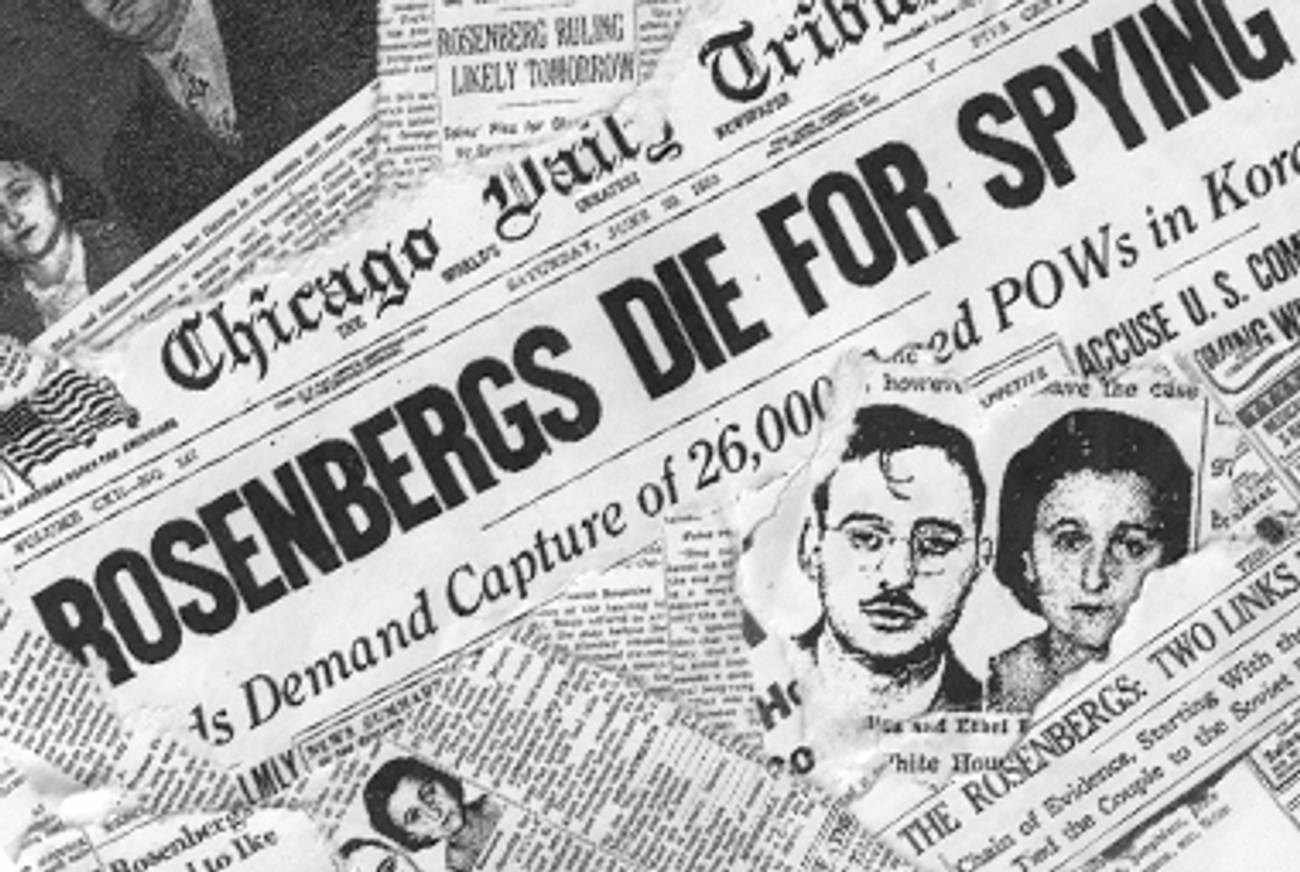

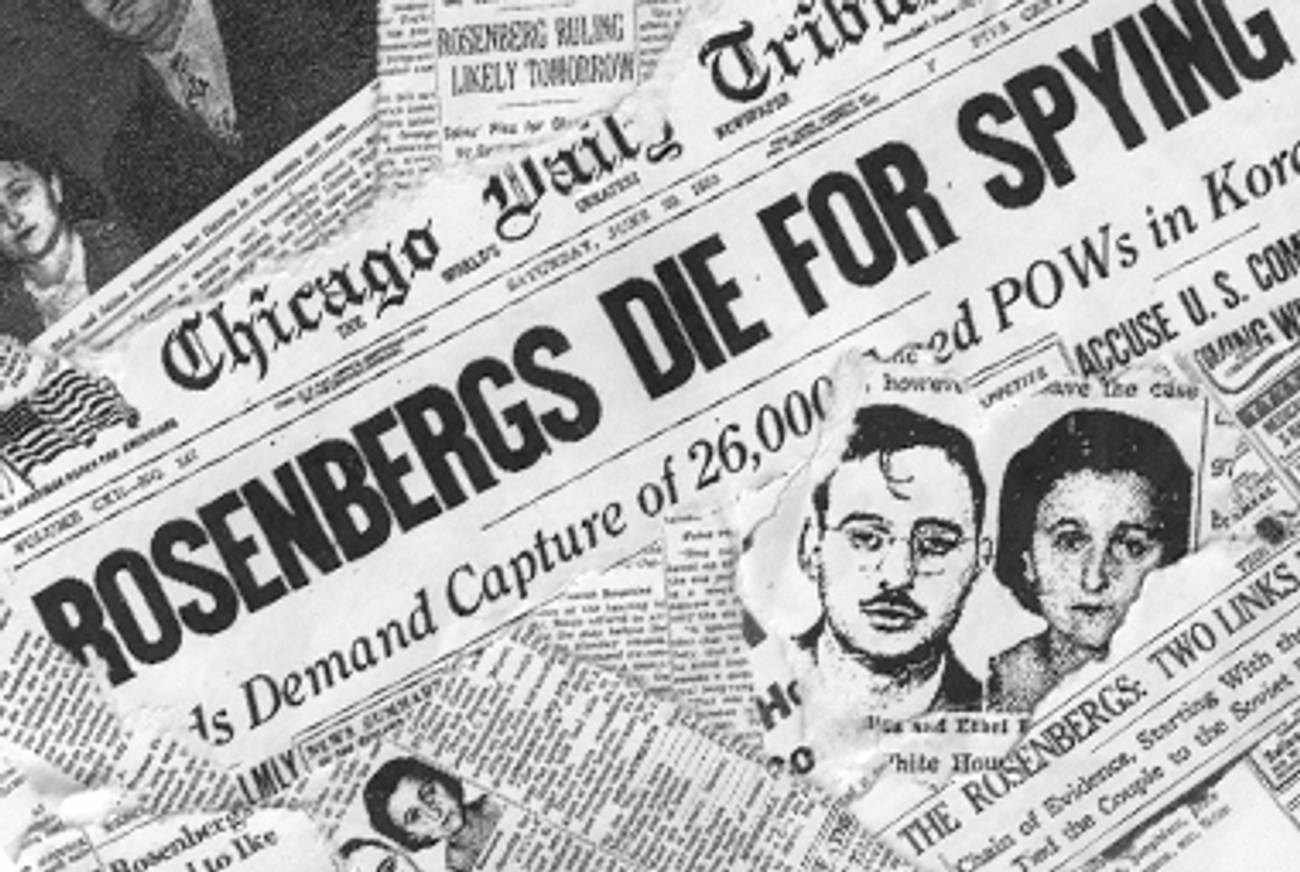

Cold Case: Ethel and Julius Rosenberg

Ethel and Julius Rosenberg were convicted of spying for the Soviet Union on March 29, 1951. Sixty years later, the case still crackles with controversy. Why is it so hard to put to rest?

Ethel and Julius Rosenberg were arrested in July and August of 1950, tried for conspiracy to commit espionage, found guilty by a jury on March 29, 1951, and then condemned to death by Judge Irving Kaufman at their sentencing a week later. I sat in the courtroom at Foley Square on that final fateful day 60 years ago, and remember my shock and that of those in attendance at the handing down of this harsh sentence, as well as the judge’s words that the couple had committed a crime that was “worse than murder.” Not only had they given “the Russians the A-bomb years before our best scientists predicted,” Kaufman told them, they had “already caused … the Communist aggression in Korea.” Millions more than the 50,000 American casualties in Korea, he added for good measure, “may pay the price of your treason.” By their action, the Rosenbergs alone had “altered the course of history to the disadvantage of our country,” the judge said. Kaufman was so proud of his speech that he brought his son with him to the courtroom so the 10-year-old could hear his father impose the dual death sentence, which was carried out in the electric chair at Sing-Sing Prison, north of New York City, on June 19, 1953, amidst worldwide protest.

It seems that every year since has brought new revelations about the Rosenberg case and reignites a debate about the meaning of the couple’s actions, the extent of what they actually did or did not do, and whether their actions did real harm to national security. Moreover, many of the Rosenbergs’ supporters still believe, as they did at the time, that the couple were innocent and made into scapegoats for America’s loss of its atomic monopoly.

The truth is that for those who accept evidence and reason, the debate should be over. Beginning with the first release in 1995 of the Venona decrypts of KGB messages to their agents in the United States, it became clear to even the most resolute doubters not only that Julius Rosenberg was a KGB agent who put together and ran an espionage ring made up of college friends who had become engineers or scientists but that his wife, Ethel, knew of and supported his activities. So, the question must be asked: Why did so many ignore the plain evidence of the Rosenbergs’ guilt? And why do so many continue to argue that the Rosenbergs were framed by the U.S. government?

The Rosenberg case was a family affair—almost everyone involved was Jewish: the Rosenbergs and the Greenglasses, those who became government witnesses against the two couples, as well as the prosecutors, Myles Lane, Irving Saypol, and Roy Cohn, and the justice who presided at the trial, Kaufman. The trial took place in New York City, which had the largest Jewish population in the world and where many Jews were still adherents of the leftist beliefs they imbibed along with their mother’s milk from the days of FDR and the Popular Front. Many in the Jewish community feared being branded as traitors. It is no wonder that the American Jewish Committee and the various groups that fought anti-Semitism at home kept their distance from the case, proclaimed that the couple was guilty, and did not join the pleas from all over the world for President Dwight Eisenhower to commute the Rosenbergs’ death sentence.

Indeed, Lucy Dawidowicz, the late scholar of Hitler’s war against the Jews, wrote in the socialist anti-Communist newspaper the New Leader that the American Communist Party was trying to use the Jews in its “war against America,” and hence no Jew who understood that should be involved in an effort to gain clemency for the condemned couple. Anti-Communists should not only oppose clemency, she argued, but should hope that the Rosenbergs’ lives would not be spared, because if judges backed away from imposing the ultimate penalty on them, it would mean America had caved in to the Party’s “moral blackmail.”

In 1983, The Rosenberg File, a book I had co-authored with the late Joyce Milton, was published. That year, Robert Leiter, then as now an editor of the Philadelphia Jewish Exponent, wrote that “one aspect of the case—its particular ‘Jewishness’—has, in all but the rarest instances, escaped wider discussion.” Commentators, he wrote, “have avoided coming to grips with it.” The concern at the time of the trial was most clearly expressed by an aide to the AJC’s executive director, who wrote a memo about their fear that “the non-Jewish public may generalize from these activities and impute to the Jews as a group treasonable motives and activities.” Jury members were aware of the issue. The foreman of the all-gentile jury told the press that “I felt good that this was strictly a Jewish show. It was Jews against Jews,” and, as he put it, “it wasn’t the Christians against the Jews.”

On the left, the Communists and their allies did all they could to attribute the indictment and trial of the Rosenbergs to anti-Semitism, which fit with their assertion—as hard as it is to believe today—that the Truman Administration was leading America toward a home-grown version of Fascism. Moreover, the Rosenberg trial coincided with the actual anti-Semitic trial of the former Czechoslovak Communist Party leadership—most of whom were Jewish. Almost all of the defendants in that trial were found guilty of spying for the United States and the Zionists and, after confessions forced by brutal torture, were hanged to death. By focusing on the Rosenbergs as victims of American fascism and anti-Semitism, the Soviets hoped to deflect attention away from what they were doing in their own bloc.

Thus the Old Left newspaper that began the first Rosenberg defense efforts, the National Guardian, explained that it was “nonsensical” to view the Slansky trial as anti-Semitic, because “in Prague the defendants have confessed in open court while the Rosenbergs still proclaim their innocence.” The newspaper went on to note that the Czech prosecutor “presented photostats and documents to support the accusations.” It is no wonder that the independent leftist journalist I.F. Stone—who believed the Rosenbergs were probably guilty (possibly because decades earlier he had himself signed on to work for Soviet intelligence)—wrote that “no picket lines circled the Kremlin to protest the execution of Jewish writers and artists; they did not even have a day in court; they just disappeared. Slansky was executed overnight without appeal in Prague. How the same people could excuse Slansky and [Stalin’s] anti-Semitic ‘doctor’s plot’ and at the same time carry on the Rosenberg campaign as they did calls for political psychiatry.”

Today, so many decades later, the descendants of the people who proclaimed the Rosenbergs’ innocence have now begun yet another campaign to rehabilitate them. They now argue that although it appears Julius Rosenberg was a Soviet spy after all, he gave little of value to the Soviets, was motivated by the desire to stave off atomic war, and in any case had nothing to do with handing over atomic information of any kind to the Soviet Union.

A new variation of this argument was penned recently by the activist historian and lawyer Staughton Lynd, writing in the Marxist journal Monthly Review, founded in 1949 by the late Leo Huberman and the late Paul M. Sweezy. I have written at length about Lynd’s article, but his argument can be easily summarized. Lynd now accepts as fact that Julius Rosenberg led a Soviet spy network, but he objects to what he calls the triumphalism of those like me who have asserted this for years. More important for Lynd is that the couple refused to “snitch,” therefore making themselves heroes. He maintains that their trial was a “sham,” and he argues that even if they were guilty, they must be viewed as unadulterated heroes. Why? Because, he actually writes, the couple had “obligations as Communists, and as citizens of the world.” So, to Lynd, the Rosenbergs’ obligation to spy for Joseph Stalin stands above any loyalty to their own country, not to speak of their willingness to make their own children orphans. Secondly, Lynd believes that if the Rosenbergs helped the Soviets get the bomb, that “might have been justified,” since he believes Soviet strength stopped aggression by the American imperialists.

For years, the American Left argued that the Rosenbergs were framed and innocent. Now Lynd says they were guilty but that their actions were justified because they helped “preserve the peace of the world.” In effect, he is saying that instead of still attempting to prove the Rosenbergs were framed, we should celebrate them for being traitors to their own country. His argument reveals only the desperation some on the left have to descend to in order to maintain their view that the only guilty party was the United States.

The innocence of the Rosenbergs has long been a touchstone of the left, and attempts to discuss evidence suggesting their guilt have been assailed as appeasement of McCarthyism. Most recently, writing in the Nation, its former editor and publisher Victor Navasky endorsed the finding of the late Walter Schneir, who argued that the Rosenbergs were framed and innocent. Walter and Miriam Schneir’s 1965 Invitation to an Inquest was the textbook for this cause, and this strain of thought continues in the latest Schneir book, Final Verdict, published in 2010, after Walter Schneir’s death. The real spy, the Schneirs claim in a new twist, was Ethel Rosenberg’s brother, David Greenglass, who they claim acted on his own and in return for his cooperation with prosecutors got off with a 15-year sentence. Never mind that in their original conspiracy book the Schneirs argued that Greenglass never engaged in espionage at all and did not hand anything over to Rosenberg’s courier, Harry Gold, who made up his entire testimony. Schneir and Navasky also ignore the incontrovertible fact that Julius Rosenberg, at Ethel’s request, recruited David Greenglass into his network.

Steven Usdin and I answered Navasky’s charges in an article appearing in the New Republic’s website last December, and I wrote a critical review of Walter Schneir’s Final Verdict that appeared in Commentary. Other publications presenting detailed and incontrovertible proof of the Rosenbergs’ guilt are The Rosenberg File; the 1995 release of the National Security Agency’s decryptions of World War II KGB cables (21 of which report on Julius’ espionage); the 2001 autobiography of Alexander Feklisov, Rosenberg’s KGB controller; and Steven Usdin’s 2005 book, Engineering Communism, which laid out the enormous extent of the Rosenberg ring’s espionage in the field of military technology. Although it is not freely available online, Usdin’s article “The Rosenberg Ring’s Continued Impact,” in The International Journal of Intelligence and Counter-Intelligence, is the single most complete source for an overview of the damage the couple did to America’s national security and a detailed account of what the Soviets got from the network. There are no more lingering doubts about the Rosenbergs’ “culpability”—except in the precincts of the dwindling true believers.

Continue reading: the Meeropols, dark secrets, and “I did it for the Soviet Union.” Or view as a single page.

As Usdin shows, the Rosenberg network, especially the agents Joel Barr and Alfred Sarant, passed on the 12,000-page blueprints for the Lockheed P-80 Shooting Star, airborne radars for nighttime navigation and bombing, and other new radar technology. “Rosenberg’s band of amateur spies,” Usdin writes, “turned over detailed information on a wide range of technologies and weapon systems that hastened the Red Army’s march to Berlin, jump-started its postwar development of nuclear weapons and delivery systems, and later helped Communist troops in North Korea fight the American military to a standoff.”

So why, then, is there still a campaign to declare the Rosenbergs innocent victims? The answer must be found in the desire of now aging New Leftists and the few remaining elderly veterans of the Old Left to keep alive their hope of proving that the United States is the main villain in the world. In an essay written about today’s Tea Party for the New York Review of Books, the historian Gordon S. Wood reflects on the differences between popular memory and history. He notes that “there has always been a tension between critical history and popular memory, between what historians write and what society chooses to remember.” In the case of the Rosenbergs, what the veterans of the old “the Rosenbergs are innocent” school desire is to keep the memory of the cause alive. To admit the couple’s guilt is to demolish in one fell swoop the case their defenders have made over the years about their martyrdom and to force their supporters to face up to issues they would rather ignore. That is why the distinguished historian Eric Foner—one of the most prominent historians in the United States—can write that “the execution of the Rosenbergs was only the most extreme example of a broader pattern of shattered careers and suppressed civil liberties”—rather than an actual espionage case in which two American Communists were recruited out of the Communist Party USA to work for the KGB.

Foner continues to assert that “rather than the nest of Soviet spies portrayed by the FBI, or creatures of Moscow … the party emerges in new [revisionist historical] work as a complex and diverse organization.” He sees the CPUSA as a legitimate political group no different than any other organization or party. But in fact, if not exactly a “nest of spies,” it was, from its top leadership down, a willing recruiting agency for the KGB. It might have been complex, but its diversity included the membership’s willingness to do whatever Moscow ordered.

Indeed, Walter Schneir inadvertently admitted as much, when he wrote in Final Verdict that if Julius Rosenberg had talked, he would have been forced to name “the very friends who he had himself recruited,” as well as reveal “the dark secret” that the CPUSA and its leader, Earl Browder, “had involved itself in enlisting dozens of members for espionage.” When Schneir writes that if Julius and Ethel Rosenberg had confessed, they would have “fueled the hysteria of the times,” he is admitting that the so-called hysteria had a real basis in fact—the CPUSA and its members’ principal loyalty was to Moscow.

The Schneirs saw the Rosenberg trial as an American show trial, in which acknowledging the truth that Rosenberg was a Soviet agent would have given their enemies—the U.S. government—invaluable ammunition for their anti-Communist policies. Ironically, the Rosenbergs and their supporters were at the same time giving their total support to a power that was holding real show trials and sending innocent people to their deaths.

When the Rosenbergs’ co-defendant Morton Sobell confessed in 2008 to Sam Roberts of the New York Times that despite his decades of asserting his innocence, he was in fact a Soviet spy, the old game ran into big trouble. Sobell qualified his confession by saying he never thought of himself as a spy, just as an individual who was helping “a wartime Soviet ally,” who only handed the Soviets “defensive” weaponry that would be of no harm to America. Moreover, Sobell also argued that the information coming from Greenglass was only “junk.”

Yet even while confessing, Sobell fudged the facts. In an article Steven Usdin and I wrote that appears in a recent issue of the Weekly Standard, we revealed that Sobell decided to admit that what he stole was in fact major military data desired by the Soviets. He told us how on a nonstop photo session over a July 4 weekend in 1948, he, Julius Rosenberg, National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics scientist William Perl, and a fourth man took films of 1,885 pages of classified documents stolen for them by Perl from a Columbia University safe belonging to Theodore von Kármán, at that time the nation’s most prominent aerospace engineer. It included information about the designs and capabilities of every American bomber, designs for analog and digital computers used to automate antiaircraft weapons, and specifications for land-based and airborne radars later used in Korea. He thus provided information that advanced the capabilities of the Soviet military machine.

Moreover, Sobell acknowledged that he engaged in this espionage not because he was anti-fascist, but, as he told us, “I did it for the Soviet Union.” His spying continued until the day he fled to Mexico to try and escape arrest in 1950, well into the Cold War, when the United States and the Soviet Union were no longer allies.

As new information found in espionage historian Alexander Vassiliev’s notebooks revealed, Greenglass had in fact not only given a primitive sketch of the bomb’s lens configuration to Harry Gold, Rosenberg’s courier, but later delivered to him the physical mold of a detonator for the bomb. The detonators were built in the shop in which Greenglass worked. Moreover, the supposedly “harmless” material the Rosenberg ring handed over to the KGB included radar specifications and aircraft designs that gave the Soviet military critical information about American capabilities, allowed the Red Army to jam U.S. radar, and contributed to the development of sophisticated Soviet fighters that equaled those deployed by the U.S. Air Force. There can be no doubt that this technology directly led to the deaths of thousands of American soldiers in Korea and Vietnam.

Sadly, the Rosenbergs’ sons, Michael and Robert Meeropol, still continue their campaign to exonerate their parents. After Sobell’s confession, Michael—the elder—acknowledged that for years “we believed they were innocent and we tried to prove them innocent.” But now, he said that they believe “truth is more important than our political position.” However, they are continuing to obscure the truth. After all, their parents went to their deaths admonishing them, in their last letter, to “NEVER LET THEM CHANGE THE TRUTH OF OUR INNOCENCE,” or as the couple put it another time, “The Fact of our innocence will not change. We are the first victims of American Fascism.”

So, it is understandable that it has been hard for their sons to let it go. Perhaps it is more painful for them to direct their anger at their parents who lied to them about their guilt, preferring to leave them orphans rather than to dishonor their pledge to serve Joseph Stalin’s Soviet Union. Robert Meeropol explained to Sam Roberts that had his farther talked, he would have had to “send his best friends to jail, and he could not do that.” He also added that “my parents would have made a bigger betrayal to avoid betraying me, and frankly I don’t consider myself that important.” Evidently, remaining silent to protect the spies he recruited was something Julius saw as sacrosanct, while allowing his sons to become orphaned was excusable. So, now his sons admit only that their father engaged only in “non-atomic espionage,” which somehow makes it appear less wrong. Of course, this is also false, since the Rosenbergs recruited David Greenglass precisely because he was working at the Manhattan Project, where they hoped he would hit pay dirt. Moreover, we now know, thanks to Spies, the book by John Earl Haynes, Harvey Klehr, and Alexander Vassiliev, that Julius Rosenberg also recruited yet another atomic spy, Russell McNutt.

The sons also claim that even if Julius was guilty, their mother, Ethel Rosenberg, was completely innocent. They make their claim on an evaluation of the once-secret grand jury hearings released by the government in 2008. That material showed that Ruth Greenglass, David’s wife, lied when she testified that material received from her husband was typed up by Ethel. In her grand jury testimony, she said to the contrary that she herself wrote it up in longhand. KGB Venona decrypts confirm that what they received was “hand-written.” (You can find my analysis of the grand jury testimony here.)

This, however, did not mean that Ethel was innocent, even though the government got Ruth to change her testimony. Venona also corroborated that Ethel had recommended Ruth, her sister-in-law, to the KGB as a suitable recruit. She also knew about her husband’s espionage work as well as that of other members of his ring, Joel Barr and Alfred Sarant. Ethel, in other words, was knowledgeable, and in legal terms was a conspirator. The fact that the government sought to break Julius by getting him to realize that his children would be left without both their parents does not prove that Ethel was innocent.

The truth is that both Meeropol sons are not what they continually claim to be: objective historians who are researching the Rosenberg case. They are partisans in the fight to prove their parents morally innocent, if not factually innocent. Michael Meeropol once wrote that his parents refused to cooperate because they wanted to keep the United States from creating “a massive spy show trial,” and they hence “earned the thanks of generations of resisters to government repression.” That statement is truly ironic, since the couple gave up their lives on behalf of the Soviet Union, the home of the show trial.

The late Howard Zinn tried to shift the terms of the Meeropols’ argument. Even if their parents were guilty, he wrote before his death, the “most important thing was that they did not get a fair trial in the atmosphere of cold war hysteria.” That statement would have had some credibility if Zinn had acknowledged the couple’s guilt. But of course he argued that most of the witnesses against them were lying. No one on the left, it seems, is willing to offer any condemnation for the way in which the Rosenbergs betrayed their own country.

There is, finally, the claim, made by Victor Navasky and echoed by others, that “these guys thought they were helping our ally in wartime.” A nice try—except the new evidence reveals two things: Julius Rosenberg set up his network during the Nazi-Soviet Pact, when the United States and Russia were not allies, and second, he kept his network alive after the war’s end, in the period when the Cold War had started. The myth that Julius was motivated by anti-fascist concerns, rather than a desire to serve Stalin, is the greatest myth of all. As David Greenglass told me personally, he and Julius saw themselves as “soldiers for Stalin.”

Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, David and Ruth Greenglass, and Morton Sobell all saw themselves as soldiers in a good fight, working behind enemy lines. They were Soviet rather than American patriots, who hid their own motivations in phony remonstrations of their supposed love for the United States.

Ronald Radosh is an adjunct fellow at The Hudson Institute and a writer for Pajamas Media. He is author, with the late Joyce Milton, of The Rosenberg File and other books.

Ronald Radosh is an adjunct fellow at The Hudson Institute and a writer for Pajamas Media. He is author, with the late Joyce Milton, of The Rosenberg File and other books.