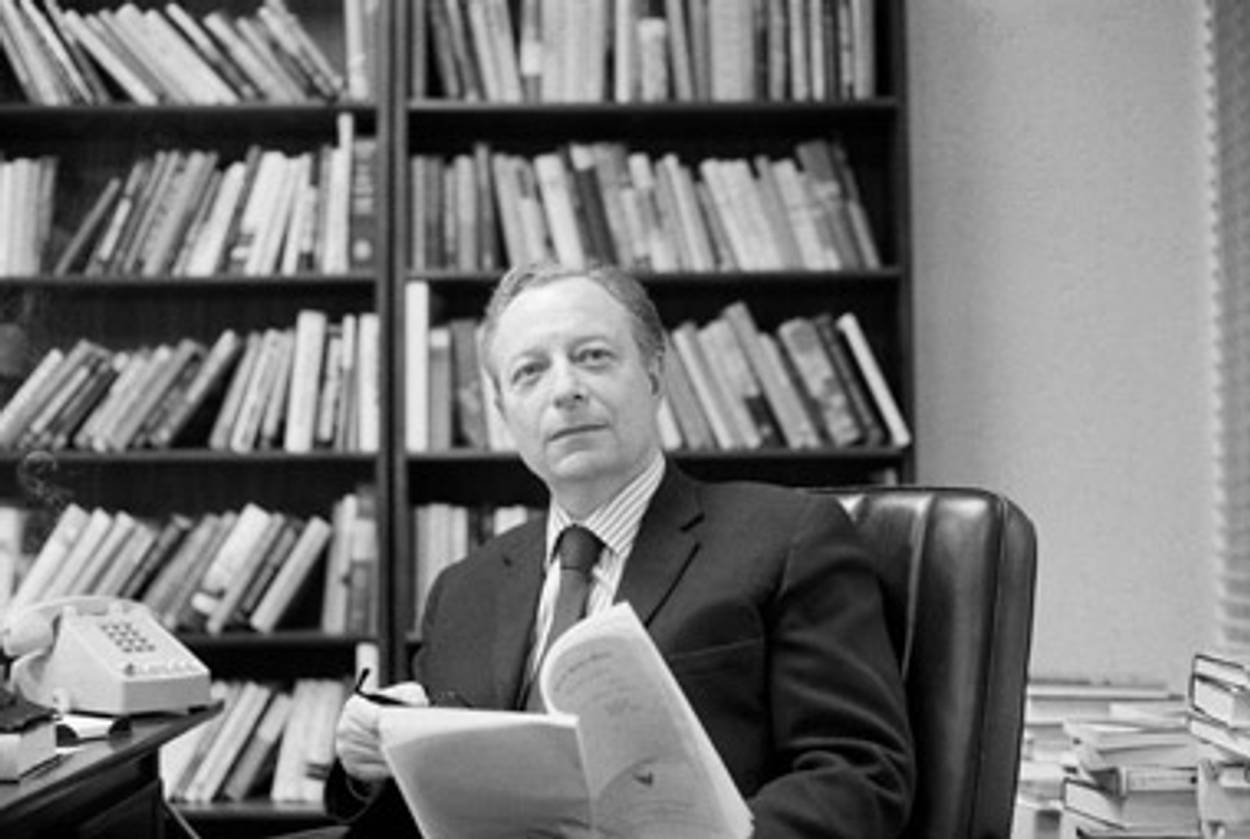

Kristol Clear

How the neoconservative columnist’s x-ray vision will be missed

The journalistic sagacity of Irving Kristol, who died Friday at 89, can be glimpsed in hundreds pieces that he turned out over the years, but the one in which I first came to appreciate his seichel was a column he wrote for The Wall Street Journal about the Argentine newspaper publisher and ex-political prisoner named Jacobo Timerman. It was published in the spring of 1981, in a season in which Timerman was being lionized on the left for his new memoir, Prisoner Without a Name, Cell Without a Number, alleging that during his detention by a faction of the Argentine military he had been tortured with electric shock treatments because he was a Jew.

Timerman had brought out his book just as the President Ronald Reagan was assembling his new administration. The Argentinean newspaper publisher was seized upon by, or offered himself to, the left and was used to testify against Reagan’s choice for assistant secretary of state for human rights, Ernest Lefever. The left feared that Lefever would focus more on totalitarian communist regimes than the authoritarian regimes on the right that, for all their sins, at least allowed the practice of religion and travel and the owning of private property—and sided with the United States against the Soviet Union. Timerman’s testimony helped convince the Senate Foreign Relations committee to reject Lefever.

At around this time, an invitation to have lunch with Timerman went around editorial page of the Journal, where I picked it up. I’d been newspapering in the Third World for much of the past decade, and the struggle for press freedom there interested me. At the lunch, hosted by Robert Bernstein of Random House, I found myself seated between a lady and a gentleman who were having a conversation across my plate. I was trying to follow it when one of them said to the other that Timerman’s financial partner in his newspaper was David Graiver. “What?” I exclaimed. “Timerman was David Graiver’s business partner?” When she allowed again that he was, I said, “No wonder he was being tortured.”

I didn’t mean to suggest he deserved torture, which I am against. I meant that it was not surprising for authorities anywhere to be interested in a business partner of Graiver, who was one of the most notorious figures in Latin America and was being probed by American prosecutors for financial wrongdoing. When the lunch was over I went back to the newspaper and telephoned Timerman’s publisher, Alfred Knopf. I said I wanted to ask about some disturbing things I’d heard and invited Timerman to breakfast. An appointment was set up promptly for breakfast a day or two hence at the Carlyle. On the afternoon before the meeting, I mentioned to the editorial meeting, “Anybody want to join me for breakfast tomorrow with Jacobo Timerman.” Journal editor Robert Bartley’s eyebrows shot up. “You’re having breakfast with Timerman? Have you seen what Irving Kristol has just sent in?”

In fact I had not, and Bartley rushed over to his desk and returned with the foolscap of Kristol’s next column, a devastating dispatch that questioned Timerman’s bona fides on almost every level and situated the affair in the context of the global struggle with the Soviet Union. Kristol began with a reprise of the distinction between totalitarian and authoritarian regimes. “A major intellectual and propaganda campaign is now being mounted by the left and liberal-left against this distinction,” Kristol wrote. “Some of the active participants are simply human rights pundits. But there can be little doubt that the driving force behind this campaign is supplied by those who have more sophisticated political intentions.”

“They understand very well,” Kristol wrote, “that once the distinction between totalitarian and authoritarian nations is eliminated, most of our attention and energy are bound to be directed toward the latter, since in fact our State Department has more influence, however limited, on the governments of Argentina or Guatemala than on Cuba or Vietnam.” He drew a contrast between the different attitudes of human rights activists toward Timerman, on the one hand, and the Cuban democratic socialist, Huber Matos, who was held in one of Castro’s dungeons, and mistreated there, for nearly two decades.

Then he dug into Timerman himself, particularly for his failure to disclose in his book key facts. “The name David Graiver does not appear in Mr. Timerman’s book,” Kristol observed. He called it an “extraordinary omission” and stated flat out that Graiver was the “immediate cause of Mr. Timerman’s arrest and imprisonment.” He sketched Graiver’s responsibility in the collapse of two American banks, from which, Kristol wrote, investigators suspected he looted as much as $40 million. He reminded readers that even though a private plane in which Graiver was supposedly a passenger had crashed into a mountain in Mexico in August of 1976, Manhattan District Attorney Robert Morgenthau suspected that Graiver might still be alive.

It was some eight months after Graiver’s death that Argentine authorities, as Kristol put it, “disclosed that Mr. Graiver had been, among other things, the money manager for the Montoneros, the left-wing urban terrorists, who had accumulated a known $60 million in ransom money and who felt that it was a shame that so much capital should not be yielding revolutionary returns.” And, Kristol reported, it had also been disclosed that “Graiver owned a 50% interest in Mr. Timerman’s paper, La Opinion.” He pointed out that it was after those allegations were made public that Timerman was arrested, “along with members of the Graiver family.”

Kristol observed that Graiver’s own motives were unclear, since he was not particularly political. Graiver had been forced to pay ransom for a family member, and maybe his own services to the Montoneros were less than voluntary. Kristol also pointed out that there was no evidence that Timerman knew what Graiver was up to. But he argued that the absence of such evidence made Timerman’s “silence on the Graiver affair all the more inexplicable”—unless it were that Timerman was less interested in human rights and more interested in indicting the regime in Argentina and our own government in Washington.

Kristol then went into a review of Timerman’s own relations—or lack of them—with the Jewish community in Argentina. Kristol didn’t deny, indeed straightforwardly acknowledged, the problem of anti-Semitism in Argentina. But he pointed out that the man to whom Timerman dedicated his book, Rabbi Marshall Meyer, whom Kristol called “a distinguished fighter for human rights,” was building a major rabbinical seminary in Argentina. And the Jewish community, for all its serious troubles, was not fleeing the country, though it was largely keeping its distance from Timerman.

From this Kristol concluded that the Jewish community was “implicitly vindicating the Reagan administration’s prudent policy on human rights”—which involved using its influence to try to move the regime toward greater liberalization. He called the outlook “far from hopeless” and warned that were we to “write off” Argentina entirely the “more extreme right-wing elements in the Armed forces—the ones who illegally arrested and tortured Mr. Timerman—would surely take power.” And he suggested that there were those on the left who would like to see such a thing happen in order to provoke a crisis that would create for them an opportunity.

It was one powerful column. Bartley, who was nothing if not an editor who liked to stay on the edge of a story, remade that night’s editorial page and put Irving’s piece in the paper a day early. He didn’t want Timerman to get the first word in. And so it was that I personally hand-carried the edition containing Kristol’s attack on Timerman up to the Carlyle and handed it to Timerman over breakfast. After a cursory glance, Timerman tossed it aside. When I pressed him about David Graiver, he confirmed they were partners but complained about the interview. “The questions you are asking me,” he said, “these are the questions they were asking me when I was tortured.” To which Mark Falcoff, in a reprise of the Timerman case issued by Commentary magazine six months later, remarked: “Just so.”

Timerman eventually settled in Tel Aviv. A few months later, while on a visit to Israel, I had a cup of coffee with the scoundrel. Looking back, Timerman had one reaction to Kristol’s piece, which is that it had done wonders for the sale of his prison memoir. He had written a new book, attacking Israel for the war in Lebanon, and hoped that Kristol or the Journal would attack that volume, too. As I walked away from the coffee shop, I found myself marveling at how right Kristol had been—at what a magnificent newspaper columnist he was, a profound thinker and scoop artist all in one. On the great political confrontations of his time, he had x-ray vision. And I can’t help thinking how much America could use him today as a new president enters a new and equally dangerous era needing all the seichel he can get.

Seth Lipsky, formerly editor of the English-language edition of the Forward, is founding editor of The New York Sun.

Seth Lipsky, formerly editor of the English-language edition of the Forward, is founding editor of The New York Sun.