The Post-Pandemic Mind

Who will command the emerging new order: conservative nationalists, digital theoreticians, or social-democratic and liberal internationalists?

Everybody wants to know what the world is going to look like in the post-pandemic future, and I can offer a prediction—not about the geography of social and economic realities, which is indiscernible to me, but about the wispy cloudscape of ideas and theories that will take shape overhead. The cloudscape of ideas and theories is easy to predict because a number of those thoughts are already floating by. Vaguely they condense into separate cloud-clusters—three of them, I think. And it is easy to foresee that, after a while, the cloudy condensations will end up darkly glowering at one another, as clouds sometimes do. Such will be the future.

It will be a debate. Its theme will be the health-and-economic crisis and its lessons, and the argument will break down into interpretations that are right-leaning, anywhere-leaning, and left-leaning. To wit: a conservative nationalist interpretation; an industrial interpretation, bearing on the digital culture; and a social-democratic and liberal internationalist interpretation. The last of those interpretations will be my own.

But each of the interpretations will seem persuasive to someone or another, beginning with the conservative nationalism, whose proponents will enjoy the special advantage of having their own people in power here and there, globally speaking. And the conservative nationalism will prove to be additionally persuasive because, during these early months of the crisis, enormous developments have been unfolding, and some of those developments have reinforced the conservative nationalist argument in one or another of its particulars.

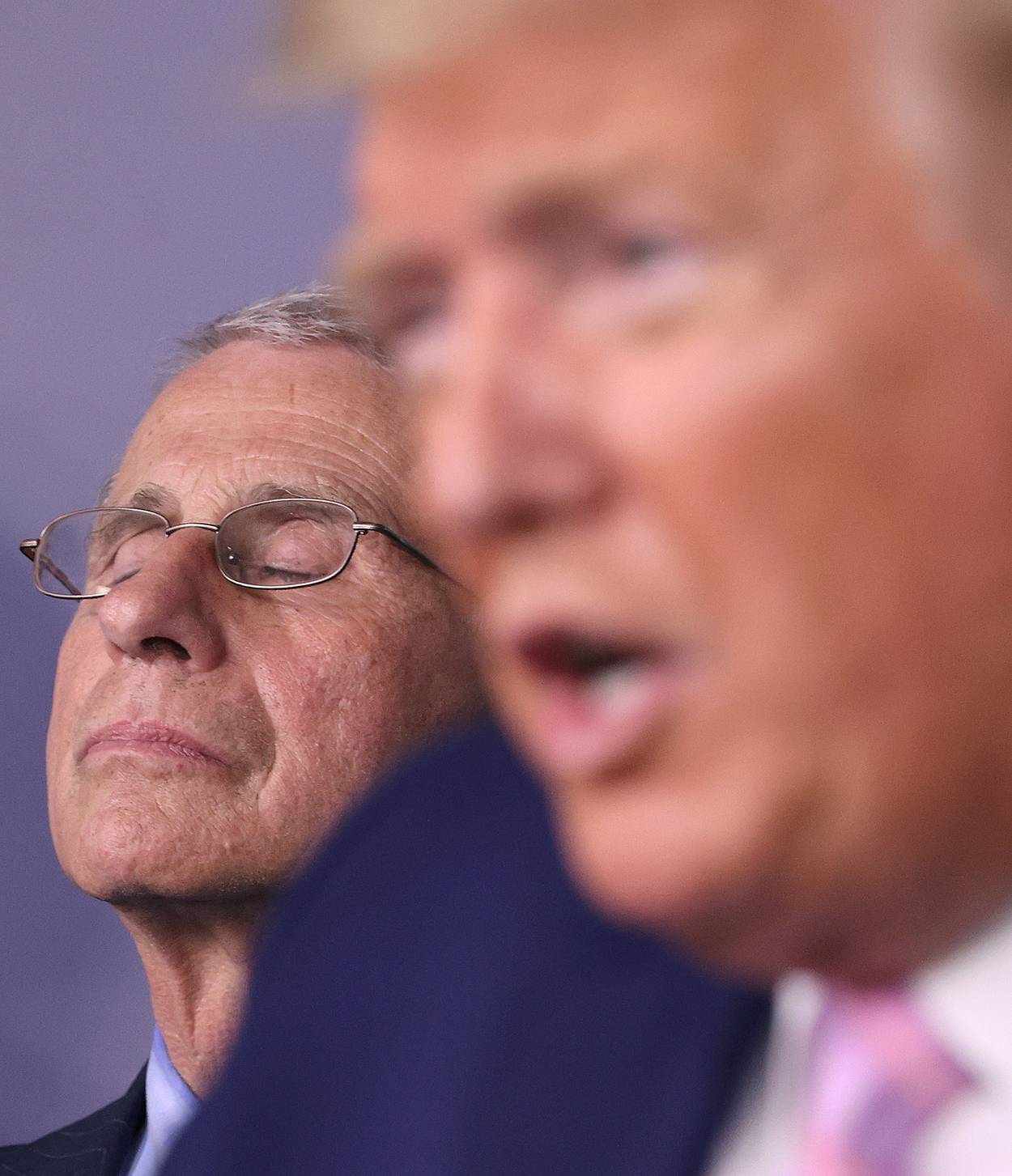

The panic over supply chains, above all—no one has failed to notice that, in regard to essential medical products, there might, in fact, be good reason for emphasizing a principle of national sovereignty. Some things ought to be manufactured at home, regardless of cost. As it happens, the Trump administration’s efforts to address the supply-chain problem—by placing tariffs on medical products from China—succeeded only in contributing to the general disaster of the early pandemic response in the United States, even if the administration backed off on some of those tariffs. Crisis management has not proved to be a Trump administration strong suit. Still, from an abstract standpoint, everyone today would have to agree that, in regard to specific necessary items, common sense and a national-sovereignty emphasis on self-reliance have dovetailed.

But the conservative nationalist argument looks strong right now also because it lends itself to multiple expositions. It is true that, in President Trump’s version, the exposition takes a folkloric and demagogic turn, in a style of populist paranoia—the storytelling about the Good People of America who have come under attack from the Foreign Enemy of the Chinese Communist Party and the sinister internationalist World Health Organization, and the WHO’s treacherous allies among the Bad People of the American elite, not to mention “Obamagate,” the “Russia hoax,” and whatnot. The Confederate flag-and-gun protests have not strengthened the case. But it would be a mistake to reduce the conservative nationalist argument to its idiotic versions and the conspiracy theories.

I notice the very distinguished and highminded Russell A. Berman of Stanford, editor emeritus of Telos, the Frankfurt School philosophical journal. Russell Berman has presented the case for a reasserted statist and perhaps populist nationalism (though he prefers the word “patriotism”) in an essay in his own journal, which turns out to be a reprint of his contribution to a more overtly political magazine called American Greatness.

He intones against the starry-eyed globalizers, he offers praise for Donald Trump’s early response to the pandemic (which he pictures as not at all inept and catastrophic, but, instead, as brave and farsighted, as you would expect from American Greatness magazine), he displays his loyalties by referring to the “Wuhan virus,” he offers a word in support of Sebastian Kurz of Austria. And yet, you could read the essay, decidedly against the author’s intentions, to be suggesting a criticism of Trump, given that conservative nationalism, in Russell Berman’s version, requires strong national institutions, capable of defending the public, and Trumpianism, as we have come to learn, is a populist attack on the state. (Or, more precisely, Trumpianism is a call for autocratic leadership in pursuit of a weakened state.)

Or the conservative nationalist position can be presented in a playful and even utopian manner, as suggested by John Gray in a New Statesman essay some weeks ago, “Why This Crisis Is a Turning Point in History,” with special attention to British circumstances. Or the argument can strike an attractively Churchillian note of defiant resistance, which Boris Johnson managed to do rather impressively in his first public statement upon getting released from the hospital (with an emphasis on British pride in the United Kingdom’s admirably socialist health service).

Or the argument for conservative nationalism can be presented on a somewhat grander scale, as in a book last year by the Israeli political theorist Yoram Hazony, of the Herzl Institute, The Virtue of Nationalism. This is a disturbing book, in my estimation, hopelessly naive about the obvious consequences of dividing the world into conservative nationalisms, unable even to imagine a liberal nationalism or to acknowledge the existence of an authentic liberal internationalism—and yet (this is the disturbing part), a book that is much admired in conservative circles here and in Israel. And why the admiration?

It is because his book rehashes in a language of political philosophy the argument against modern America that Gore Vidal used to lay out—the argument that considers America to have been an attractive republic in days of yore, when it was nobly isolationist, and then to have become, as a result of its victory in World War II, an imperialist tyrant. The argument is a rejection of the post-WWII international order.

It seems to me a big mistake for an Israeli to veer in that direction, but the argument does have a power, if only because it appeals to people on the radical left as much as on the conservative right. And, to be sure, in France the right-wing philosopher Michel Onfray is about to launch a new magazine with a left-wing name, Front populaire, to promote the doctrines of national sovereignty in a fashion that he promises will be right wing and left wing at the same time, with support from the old radical Socialist politician Jean-Pierre Chevènement and, then again, from figures of the extreme right, unto the medical doctor, Didier Raoult, who is France’s champion of hydroxychloroquine. There it is, in sum, the new intellectual formation, just now taking shape: from Telos magazine in California, with its left-wing origins, to an essay in the New Statesman, to the British prime ministry, to the Herzl Institute, to the forthcoming Front populaire magazine, plus several other magazines that I should have mentioned—which is enough to indicate that, in the age of Trump, conservative nationalism has yielded a bouquet of philosophies that are going to outlast Trump himself, and meanwhile will make him appear to be more sweetly scented.

Then again, events around the world seem to confirm the second interpretation, too—the interpretation of the crisis and its lessons that I am describing as industrial. The Spanish flu in 1918 did not bring about any particular technological transformation, and did not transform the culture. But COVID-19 has launched the entire civilization into the digital transformation and its cultural consequences in a matter of weeks. The lockdown was announced, and, by later in the same afternoon, hundreds of millions of people were staring at curious new apps on their electronic devices and saying to themselves, “I wonder if I can get this to work.” They got it to work.

The online school lessons and university classes, the Zoom dinner parties and Passover Seders (my computer screen and I attended one of those) and all the rest may have gotten underway as emergency measures. But everyone realized in a matter of days that, like the various conservative nationalist arguments, a good many of those measures are destined to survive the emergency. Telemedicine, marginal until now, has been “consecrated,” as the French say. The robotization of industry, which, like aging, is a one-way street, has been given the biggest encouragement it has ever received.

A good deal of quotidian travel has been revealed, in the snap of a finger, to be no longer necessary. Face-to-face office work is obviously not going to disappear. But no one will forget that a solution to rush-hour traffic has been discovered, and it is the home office. And why, in the age of Zoom and Skype, should anyone go on arduous and expensive business trips? Reasons to do so may still exist, but the reasons will not be as obvious and compelling as everyone had previously supposed. And what will happen to downtown business districts, in the age of the digital meeting? The home office will kill the office suite. Maybe cities will have to survive as cultural centers. Concerts will be the draw. Then again, the Metropolitan Opera demonstrated at its At-Home Gala in April that a Skype concert performed by musicians in their homes all over the world might have its curious virtues, too, which is bound to be true of theater, as well. New chapters in the history of the performing arts are about to be written.

And yet, these many developments and still more utopian fancies of the sci-fi imagination signify the triumph of a handful of digital corporations and their owners. Those organizations have ended up, in a matter of weeks, accumulating an extraordinary new degree of power over society as a whole. And this development, which is taking place before our eyes, is bound to bring about an immense conflict, sooner or later. It will be the same conflict that always breaks out when new technologies or modes of production conquer the world. The triumphs of Cornelius Vanderbilt and his steamboat ferries and railroads set the pattern, as expounded by his son’s immortal capitalist-pig slogan, “The public be damned.” And a terrible pattern it was, back in the 19th century—a pattern of class wars, rendered still more desperate by the recurring economic “panics.”

Will our own pattern be as terrible? Will our own struggles be rendered far more angry by the economic catastrophe? The struggles will, in any case, fly banners of every stripe, as in the past—anti-monopolist, social egalitarian, trade unionist, moralist, libertarian, authoritarian, individualist, communitarian, national, forward-looking, backward-yearning, sensible, apocalyptic, or anything at all, so long as hostility to the newly empowered digital colossus is expressed. But all of that lies in the future.

As for the third participant in the coming debate, the champions of a social-democratic and internationalist interpretation—those people have spoken up less than forcefully, so far. And yet, events reinforce their own arguments, too, and do so with perhaps still more power. “The age of big government is over,” said President Bill Clinton in 1996; and the age when people used to say that sort of thing came to its own end over the course of March 2020. Even the Germans, who gave such haughty lectures on austerity economics to their Greek neighbors not many years ago, have adopted a different tone—the Germans, who, having undermined the European Union in the past by declining to take responsibility for the poorer countries, and by declining to think of the EU as an authentic collectivity, have now unexpectedly offered to join the French in fortifying what they used to weaken.

The speed in the United States with which Congress adopted some $3 trillion worth of programs in the CARES Act and other measures has represented the same kind of turnaround. Naturally, the American sums are far from sufficient, and have already been watered down still more by what appears to be a positive zest for corruption on the part of the Trump administration. Even the commitment to public health expenditures will probably end up, given the nature of the administration, befitting the private hospital corporations more than the health care system itself.

The trillions of dollars represent an historic development, even so. The economically orthodox like to suppose, to the contrary, that all of this is merely an exceptional and pragmatic response to an unusual circumstance, and not any sort of revolution in the world of political and economic thinking. But the economic crisis is going to be with us for a while, and likewise the newly Keynsian responses; and, at some point, a long-lasting exception ceases to be exceptional.

There is a certain look to these developments, too, which suggests more than pragmatism. The crisis has engendered a public spirit, visible originally in Italy, and then elsewhere—a spirit of public admiration for the medical workers, a spirit of volunteerism: a spirit, finally, of altruism and generosity. In the United States, it has become easy to shrug at the people who bang pots at 7 p.m. and sing and shout from the balcony. But does anyone really doubt the sincerity? It was no small thing to watch medical volunteers from around the country make their way to New York in their own ambulances in the worst days of the crisis, in order to take their positions at what, in a time of war, would be called the front.

Everybody recognized those scenes. They were a new expression of the spirit that sprang up spontaneously in the hours after the attack on Sept. 11, 2001. And, just as in that period, the revived spirit has expressed a double sentiment—a feeling among masses of people who insist on contributing with their own hands to the safety of society, combined with a sudden recognition that society as a whole is ultimately animated by people who do get their hands dirty. Maybe the spirit expresses something additional—an idea that life cannot merely be a struggle for personal advantage: an idea that risking death in the struggle against mass death represents the social sense at its profoundest. A sense of moral sobriety. A deepening of the idea of what it is to be a human being.

The crisis has engendered a public spirit, visible originally in Italy, and then elsewhere—a spirit of public admiration for the medical workers, a spirit of volunteerism: a spirit, finally, of altruism and generosity.

And all of this does lean in a certain direction, politically speaking. This is toward the impulse that has been stirring in the Democratic Party for several years now—namely, a yearning for a return to the Progressive and New Deal traditions of big-government egalitarianism, which are the barely remembered traditions of Woodrow Wilson, and the better-remembered traditions of Franklin Roosevelt, and their heirs. Joe Biden defeated Bernie Sanders in the primary race partly because Biden convinced a lot of people that Bernie’s New Deal-style Medicare for All was going to be riskier and more expensive than an employer-based insurance.

But now that nearly 39 million people, as last reported, have lost their employers in a period of just over two months, the argument against employer-based insurance has begun to look a tad stronger. And it has been striking to see how quickly the recognition has just now emerged of social inequalities in the face of the pandemic, afflicting black and Latino populations and the meatpackers whose portraits were sketched more than century ago in Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle. So there has been a reinvigoration of the social conscience, even apart from the turn away from orthodox economics, and the reinvigoration has been visible in the Democratic Party and in parts of the press.

Here, then, are the elements for a social-democratic tidal wave—popular, spontaneous, theoretical, mass, individual, idealistic, pragmatic, profound, religious, and secular, drawing on revered traditions of American social reform, rendered cheerful by mass movements of the young, and echoed and supported by a number of parallel developments in Europe.

The question of internationalism, as the alternative to conservative nationalism, is more complicated. The retreat from internationalism has been a long time coming in the United States. President Barack Obama gave a few early indications of it some years ago, if only in regard to the greater Middle East—though he remained resolutely internationalist in regard to global and Atlanticist institutions, and especially in regard to the science questions, which are climate change and public health.

But President Trump has leapt off the cliff, such that, under his command, America has abandoned even a nominal opposition to dictatorships, and no longer offers any leadership at all, and prefers instead to roam the planet as a Lone Ranger on select and narrow issues (Israel-Arab negotiations, the Islamic Republic of Iran, the Maduro dictatorship in Venezuela), without even pretending to be pursuing a principle. And the ultimate step in that development has turned out to be an “America First” retreat from America’s primacy in the first of all fields right now, which is global science. The symbol of that retreat was the withdrawal from the Paris Agreement on climate change, which took place formally in November 2019, just as the biological event in the Wuhan wet market (it seems) was getting underway.

But the crucial retreat began with the Trump administration’s handling of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. This was the appointment (by Trump’s secretary of health and human services, who, having aroused a suspicion of corruption, was obliged to step down) of a new head of the CDC, who, having aroused her own suspicion, was likewise obliged to step down, followed by an interim appointment of a qualified person, who stepped down, followed by the appointment of still another new head, Dr. Robert Redfield, whose evangelically influenced response to the AIDS epidemic some years ago aroused a different dismay in the ranks of the American public-health specialists, a number of whom departed from the CDC, as could have been predicted.

The battered CDC that survived went on to commit serious blunders at the beginning of the crisis. Meanwhile the administration made the foolish decision to further diminish the CDC’s capabilities by withdrawing, over the course of 2018 and ’19, some of the CDC staff from China, which was compounded by a decision to end the funding for the very program that had enabled USAID people to work with Chinese investigators in Wuhan on zoonotic research.

In these ways, Trump plucked out America’s eyes. If he went on to allow himself to be deceived or misled by Chinese reassurances in the early days of the plague—if he outdid himself in the matter of praising dictators by praising Xi Jinping himself, at the very moment when Xi was fatally deceiving him—it was because his own administrative decisions had left him vulnerable and naïve. The con man chose to be a mark. The decision to be a mark was, in its fashion, a principled decision, based on the pitchfork yearning to disembowel the state—which, in this instance, meant the intelligence agencies, as well. And then, once the epidemic had ceased to be merely Chinese, the president adopted a consistent policy, domestically and internationally, to abdicate every sort of responsibility—domestically in favor of the 50 state governments; internationally in favor of Chinese leadership (while claiming to be the enemy of Chinese leadership, of course); morally, in favor of an American role as merely one more obstructive player in a worldwide scrimmage over medical supplies; and scientifically, in favor of quackery and rumor.

Contempt for the World Health Organization became the emblem of all this—the WHO, which the administration quietly undermined (by failing for three years to appoint a senior American medical representative to the WHO executive board, which left the WHO weaker in the face of the Chinese authorities, who exploited their lucky break by leaving the organization in the dark for a while about the new virus, which led to a week’s delay in calling the pandemic a pandemic, which contributed to fatal miscalculations in Italy, which may have contributed yet again to Trump’s tragic reticence to comprehend the scale of the danger). Contempt for the WHO proved to be unfortunate still again by leading the administration to ignore the American scientists who, through their connections to the WHO in its Geneva headquarters, did learn about COVID-19—the American scientists who tried, with no success, to alert an administration back in Washington that, at its topmost level, was determined not to be alerted.

And then the topmost level went all the way and announced a freeze on American contributions to the WHO, amounting to approximately $400 million since April, which was a shocking turn of events in the midst of a pandemic. Or, the turn of events was doubly shocking, given that, back in 1948, the WHO was one of the global institutions that America helped to create, as part of the very grand effort in those days to bring about the better world that Yoram Hazony, in his The Virtue of Nationalism, regards as an imperialist misfortune. Perhaps the administration was not too clever, either, in refusing the WHO’s early offer of tests. And yet, even today we in the United States and people all over the world are dependent on the WHO because of the work it is doing on COVID-19 and other infectious diseases in the poorest countries—which, as in Africa, will continue—by American decision!—under Chinese leadership. An American nationalism, in a grotesque version, is, in short, having its day.

Still, the story does have another side. The Democratic Party has shown itself to be a two-headed beast, in regard to nationalism and internationalism. If you were to judge from the primary debates over the fall and the winter, you might conclude that, in the age of Trump, the internationalist party of Franklin Roosevelt and Harry Truman believes in paying lip service to NATO and sundry global institutions, but is not really concerned with other parts of the world, except from the standpoint of getting America’s troops home as quickly as possible.

And yet, if you were to judge from the impeachment hearings and trial, the Democrats do seem to be the internationalist party. The loathing that Democrats feel for Trump and his Russian collusions and his effort to shake down the Ukrainian democracy, which is a partisan emotion, has also been a small-d democratic emotion. The Democrats feel their emotion because, in the most ancient of American traditions, they are, in fact, averse to dictators—or, at least, sometimes they are. Their hearts do beat in solidarity for struggling democrats in dark corners of the world—or, at least, sometimes they do, in arrhythmic bursts that might worry a cardiologist. Global responsibility—sometimes they do feel it. Their internationalist impulse has found its echo in Europe, too, in Angela Merkel’s surprising decision (just to underline that, even among the world’s conservatives, the Trumpian instinct is less than universal) to strengthen the European Union.

But the big new impulse that has begun to point in internationalist directions is scientific. Nationalism isolates; science internationalizes. The American agencies under the Trump administration withdrew from international collaborations; and scientists in the United States and around the world and somehow even in China threw themselves into international collaborations.

Everyone sees this. Everyone understands that reliable therapies or vaccines, if they do end up being created, will almost certainly emerge from an international consortium of some kind, informal or otherwise, even if one or another individual laboratory will make the final breakthrough and one or another national leader will blow his own bugle. It will be an achievement of the Republic of Science, and not of any other republic—an achievement of the internationalist spirit, which has become a force around the world, not because of any particular wave of ideological fervor but because science is the original internationalist, and the age calls for science.

Three vast idea-clusters, then, condensing overhead to produce the coming debate: a conservative nationalism, in several versions; a brewing rebellion against the digital corporations, barely visible for the moment and not yet ideologically defined; and a turn toward social democracy and liberal internationalism. The idea-clusters are contradictory, and, then again, are capable of merging or compromising with one another. And when they are fully formed and have displayed their relative strengths and intensities, how will things look?

Dearly I wish I could announce that winds and breezes of every sort are blowing in favor of my own inclinations, and social-democratic egalitarians are destined to win the economic and social argument. I wish I could announce that militants with a liberal disposition are destined to preside over the coming rebellion against the digital corporations; and the champions of a revived liberal internationalism are likewise destined for success; and likewise the principles of science. And, to be sure, when I look around, the indications do seem. ...

But prophecy is hex: the lesson of 2016.

Paul Berman is Tablet’s critic-at-large. He is the author of A Tale of Two Utopias, Terror and Liberalism, Power and the Idealists, and The Flight of the Intellectuals.