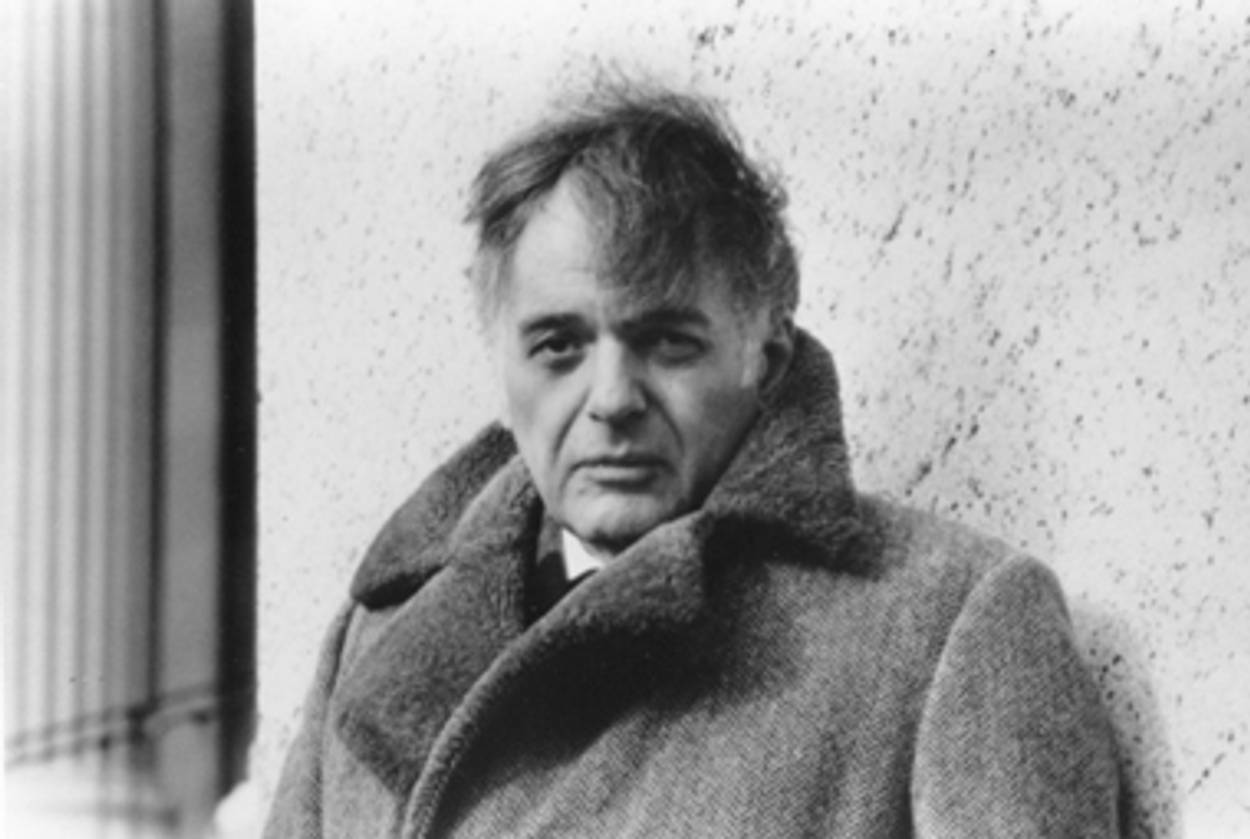

Re-remembering Yerushalmi

Reflections on a former professor and his posthumous fiction debut

Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi, who passed away in 2009, was known as a groundbreaking historical scholar whose “meditation on the tension between collective memory of a people and the more prosaic factual record of the past influenced a generation of thinkers,” Joseph Berger wrote. This divide, between historical facts and collective memory, is something Yerushalmi dealt with his entire life. As Marissa Brostoff explained in Tablet, his ability to explore this tension made him stand out as “an unusually erudite and wide-ranging thinker who made the concerns of Jewish history universally interesting.”

In the spring of 2007, I was fortunate enough to enroll in his final class at Columbia University and experience his teachings first hand. While the class was primarily made up of devotees—and make no mistake, he had many—as a philosophy major, this was the first and only history class I ended up taking. Even for me, a history novice, his clear thinking and beautifully wrought narratives brought life to the stories he told.

Praised primarily for his historical writings (most famously, Zakhor) and his teachings at Columbia, Yerushalmi hadn’t been known for his fiction. Until now. This week’s New Yorker features his posthumous debut, Gilgul (subscription required). The story within a story deals with themes familiar to Yerushalmi, touching on messianism and reincarnation (or gilgul).

In the story, Ravitch, himself a historian who has written a study on the Jewish tales of Sacher-Masoch, visits the sorceress Gerda at the behest of one of his friends. While at the time he has no interest, life’s events four years later, including the divorce from his wife and his father’s death, leave him overwhelmed with the need to visit her again. Gerda speaks in riddles of sorts, as all good sorceresses do, and tells him the story of a man who was “pathologically rest-less.” While he had no desire to travel, the man felt a strange compulsion that would constantly drive him away from wherever he was settled. Gerda explained to him that while he was born in Bucharest, his soul was the soul of Isaac Benveniste, a 15th century physician born in Spain and exiled during the great expulsion of 1492. He tried to reach Israel, but ended up dying in Rhodes. His restlessness is what inhabited him. Ravitch, captivated by the story, asks her if this is the source of his troubles as well. But all Gerda tells him is, “this story was meant for you, but is not about you.” Like Ravitch, we are left wondering about the meaning of such a tale and how this fits into our lives.

On the New Yorker website, Yeushalmi’s widow, Ophrah, discussed her husbands work with fiction editor Deborah Treisman:

Do you know whether this story—or, at least, the story within the story, the history of Isaac Benveniste, the fifteenth-century Spanish Jewish physician—was drawn from his historical research?

It calls on some basic themes that occupied him, such as exile, Israel, the Diaspora, and more. And the choice of a Sephardic name—Benveniste—hints at that; his major historical research was in Spain, and resulted in his book “From Spanish Court to Italian Ghetto: Isaac Cardoso,” about a seventeenth-century Spanish Jew, who abandoned his post as court physician in order to live openly as a Jew in Italy.

Ophrah goes on to explain that Yerushalmi never expressed any desire to publish the story (“if Yosef hears of this somewhere…he will be astounded”), but a colleague convinced her of the merits of publishing posthumously. She also expressed the hope that the story would “bring him out of his ‘professor’ box and to a new audience.”

This Week in Fiction: Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi [New Yorker]

Related: History and Memory

Miriam Krule is on the editorial staff of Slate Magazine where she edits the religion column Faith-Based. Follow her on Twitter @miriamkrule.