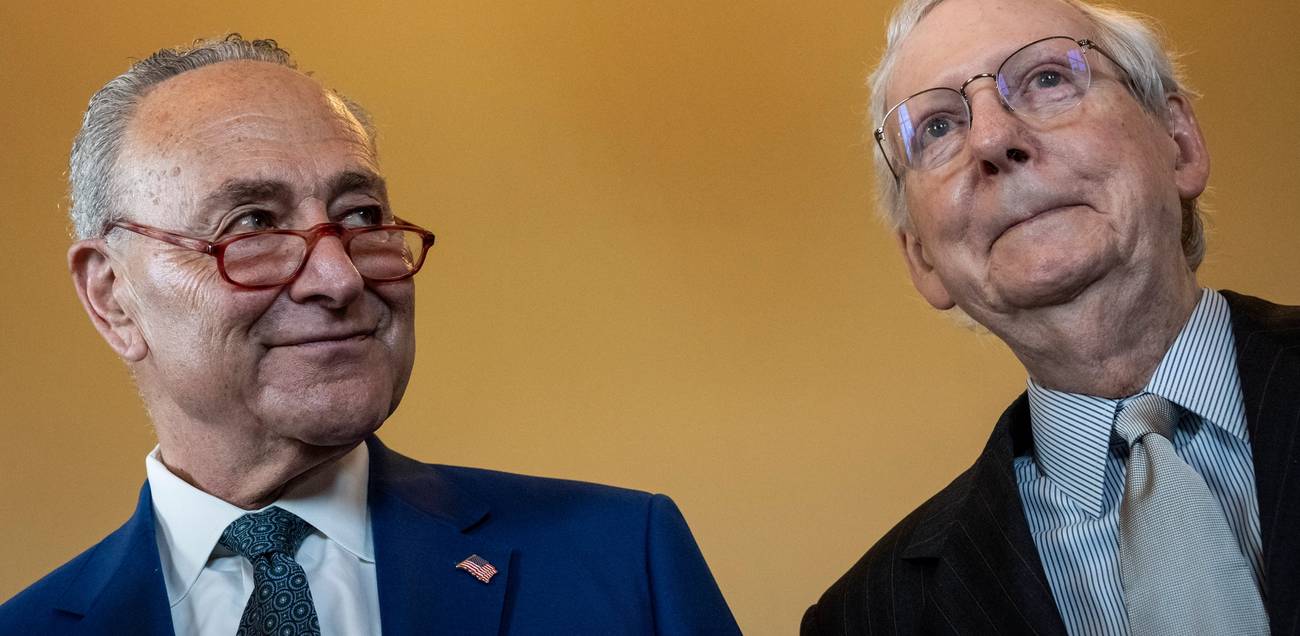

The Senile State

Our politicians are not too old—but their ideas are

Drew Angerer/Getty Images

Drew Angerer/Getty Images

Drew Angerer/Getty Images

Does America have a gerontocracy problem? A look at the leading contenders for the White House in 2024 might suggest that it does.

When Joe Biden was inaugurated at 78 he was older than Reagan was when he left office after eight years. In 2024, Biden will be 81 and Trump 78. A Biden-Trump rematch in 2024 would be a showdown between geezer gladiators.

The problem of gerontocracy is easy to exaggerate, however, because Biden and Trump are not typical of recent presidents. At their inaugurations, Obama was 47, George W. Bush 54, and Bill Clinton 46. And the U.S. House of Representatives is getting younger. While the median age in today’s Senate is higher than ever at 55.3 years, the median age of members of the current 118th Congress is 57.9 years, down from the 117th’s median of 58.9.

Moreover, elderly presidents, senators, and members of the House do not have elderly staffs. In the current Congress, the average age of Senate staffers is 33 and the average age of House staffers is 32.

Elderly Supreme Court justices have clerks just out of law school to do research and draft opinions. Much of the actual work of government in Washington in every branch is done by men and women between their 20s and their 60s.

While upper age limits on government service should be considered, term limits regardless of age will always be a terrible idea. If they were enacted, the only people in Washington with institutional memories and knowledge of how government works would be lobbyists, senior staffers, and elite bureaucrats, who could take advantage of the ignorance of newly elected novices.

Moreover, outside of the White House, a generational transition in American politics is taking place. Sen. Dianne Feinstein, the oldest member of Congress at 90, has announced that she will not seek reelection. In the House, 52-year-old Hakeem Jeffries has replaced 83-year-old Nancy Pelosi as the Democratic leader and speaker of the House in waiting. Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, 81, has suffered from increasing debility and was caught on video last month freezing in the midst of a press conference before being escorted away by a top deputy after staring silently at assembled reporters for 19 seconds. But even the long-serving McConnell at some point will be replaced.

Yet the major generational problem in politics does not involve the declining acuity of old politicians. It arises from the nature of political careers. If we exclude true opportunists, many if not most career politicians have formed their basic worldviews by the age of 30 or so, and for the rest of their careers they interpret events and new information using these preexisting intellectual filters. Our political system has had a hard time keeping up with events because it is led by people whose formative views were shaped before the fall of the Soviet Union.

Outside of the White House, a generational transition in American politics is taking place.

In my personal experience of city, state, and national politics, there are two kinds of politicians: those who want to do something and those who want to be somebody. The former are idealists and the latter are opportunists.

Idealists are far more common in the political class than the caricatures of politicians as money-grubbing hypocrites that American culture would suggest. Some politicians who were not rich when they ran for office do get rich out of public service or later lobbying or business careers that their public service made possible, and the shameless buckraking of recent ex-presidents like Clinton, Bush, Biden, and Trump—with their six-figure speaking fees and other grifts—has been a wonder to behold. But it is easier to make money in finance or consulting or real estate or movies and television than it is to make a fortune by serving multiple two-year terms in the House or dashing from hearing to hearing in the Senate between phone calls to arrogant rich donors.

In the hearts of many of the most seemingly corrupt middle-aged or elderly politicians burns residual sparks of idealism that motivated them in their youth, like magma deep beneath a dormant volcano. Over the years they learned to sacrifice their principles for success as they worked their way up the ladder. They justify this by telling themselves that they are sacrificing lesser principles to gain the power to accomplish more basic goals. Inside the leathery 70-year-old Democrat who schemes to appropriate campaign money for personal use is the young campus activist who dreamed of a utopian new order founded on social justice. Inside the Republican dinosaur who stumbles from fundraising dinner to fundraising dinner is the ardent libertarian who was inspired at the age of 13 by reading Ayn Rand’s Atlas Shrugged.

Successful politicians simply do not have as much time to read widely and consider alternate viewpoints as they did when they were college students or young activists. The day-to-day work of campaigning and governing takes up most of their time and energy, and there is little time to reflect on whether they should modify their basic assumptions—something few people do in any walk of life.

The problem, then, is that in the normal course of politics those whose political worldview froze when they were 26 or 30 finally ascend to a significant position of power only at the age of 50 or 60 or 70. Now that they are in a position to actually influence policy, they naturally tend to try to carry out a program that they were committed to in their youth, despite the fact that rapid technological or economic or social change may have already rendered many of their assumptions obsolete.

The sunny vision of the future shared in different ways by John F. Kennedy, Lyndon B. Johnson, and Ronald Reagan, was typical of their own generational cohort. The optimistic worldviews of Kennedy, Johnson, and Reagan were shaped by the experience of recovery from the Great Depression, the battle against totalitarianism, both fascist and communist, and the promise of technology. The New Frontier and the Great Society were attempts to finish and extend the New Deal. Cold War liberals and Cold War conservatives alike tended to equate the cautious, opportunistic Soviet Union with recklessly aggressive Nazi Germany and Japan, and feared to repeat “the lesson of Munich” that appeasement could lead to world war.

In the 1960s, Reagan sounded at times as gloomy as his fellow conservatives. But once in the White House, Reagan reverted to the New Deal era rhetoric of his younger self, who had voted four times for FDR, had campaigned for Truman, and had been a co-founder of Americans for Democratic Action (ADA) alongside liberal eminences like Eleanor Roosevelt and Arthur Schlesinger and John Kenneth Galbraith. To the horror of “paleoconservatives” who worried about the decline of Western civilization, Reagan offered voters—many of them, like him, from the Depression and World War II cohort—a modified version of the same optimistic vision of Kennedy and Johnson, with more market and less government. Indeed, the most frequent historical precedent held up by Reaganite supply-siders in the 1980s was Kennedy’s “supply-side” tax cut. For Reagan, the 1980s were the late 1940s and early 1950s all over again—“morning in America,” not the twilight of the West.

Like any interpretation of politics, generational analysis can be taken too far. My purpose here is to emphasize the mismatch of policies suited for one era by a politician who comes to power a generation later. Reaganism’s optimism, seeing the defeat of communist totalitarianism leading to global peace and free trade—the same vision held by liberal internationalists in the 1940s—may have been emotionally appealing but it was wrong. In reality, U.S. manufacturing as well as global economic and military power declined.

Today we can detect echoes of ’70s conservatism and liberalism in Washington. Republican Sen. Mitch McConnell was first elected to public office as a county judge/executive in Jefferson County, Kentucky, in 1977, after working for the Ford administration and other Republicans in Washington earlier in the decade. Until 1981 the maximum U.S. income tax rate was 70%; it was cut to 50% under President Reagan beginning in 1982 and lowered further to 38.5% in 1987. Since then, the central obsession of McConnell’s superannuated wing of the Republican Party has been tax cuts for the rich, lowering the top rate to 35% under George W. Bush and 37% under Trump, with Democrats boosting it slightly when they are in power.

Under Joe Biden, who became U.S. senator from Delaware in 1973 at the age of 30, the Democratic party is replaying another episode of That Seventies Show—the one about renewable energy. The Green New Deal and the rest of the Democratic Party’s energy policy is a relic of the 1970s, when two events crystallized the party’s fetishization of solar and wind energy. In 1976, the activist Amory Lovins published an article in Foreign Affairs, “Energy Strategy: The Road Not Taken,” in which he called on the U.S. to abandon nuclear energy and fossil fuels in favor of a ”soft path” based on solar power and other renewables. The Three Mile Island nuclear power plant accident in 1979 completed the demonization of nuclear power by the left. One result is the Inflation Reduction Act passed by the Democratic Congress under Biden, which largely consists of subsidies for solar and wind power as well as associated technologies like batteries and charging stations. The transition to a wholly renewable economy remains as much a mirage in the 2020s as it was in the 1970s. According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, in 2021 only 12% of U.S. primary energy consumption came from renewables, defined broadly to include wood, biomass, and biofuels—and less than 5% came from wind and solar combined.

Donald Trump’s worldview seems to reflect a different version of the 1970s. He was 22 in 1968 and only 34 in 1980. Trump’s reference to “American carnage” in his inaugural speech brings to mind the condition of the U.S. in the 1970s, with declining industries, racial tensions, riots, a crime wave, strikes, gasoline shortages, runaway inflation, and economic stagnation—and, in New York City, garbage collector strikes, graffiti everywhere, and neon porn shop signs all over Times Square. From the 1970s to the 1990s that urban experience produced a political backlash, particularly among white working-class voters, that led to the election of a number of mayors, including the Democrat Ed Koch in New York City, who ran on promises to crack down on disorder and crime, a tradition to which Trump and his ally Rudy Giuliani belong.

The real problem, then, is not superannuated politicians, but politicians with superannuated preconceptions. We need fewer idealists of all ages who go into politics to do something, and later mistakenly try to do it after the world has changed, and more flexible opportunists of all ages who don’t want to do anything in particular but just want to be somebody important.

Michael Lind is a Tablet columnist, a fellow at New America, and author of Hell to Pay: How the Suppression of Wages Is Destroying America.