Tel Aviv Museum of Art Takes on Global Catastrophes

Part exhibition, part research project, part community activism, the exhibition showcases ‘constructive responses to natural disasters’

In April 2015, an earthquake clocking 7.8 on the Richter scale flattened villages and killed thousands in Nepal. The world’s horrified citizens followed along in real-time over social media, as an avalanche mowed down trekkers on Mount Everest, centuries-old temples collapsed upon themselves, and some 3.5 million Nepalese found themselves, in one earth-swinging second, homeless and in desperate need of temporary shelter.

Maya Vinitsky, a curator at the Tel Aviv Museum of Art in the Department of Architecture and Design, was watching along with the rest of the world. And she was both fascinated and inspired to learn about a small Nepalese village called Takure, where volunteers from a local NGO had brought in a brick press, mixed a combination of soil and local sand, and created thousands of homemade bricks to rebuild community schools, orphanages, and homes in wiped out by the temblors.

The Brickmakers of Nepal, as they have come to be called, are among the dozens of grassroots shelter-bearers featured in a new exhibit at the Tel Aviv Museum of Art, one which focuses on the structures, flimsy to pop-up and everything in between, that stand in as homesteads in the face of natural disasters across the globe.

Part exhibition, part research project, part community activism, Vinitsky’s 3.5 Square Meters: Constructive Responses to Natural Disasters, marks the first attempt from the gleamingly renovated Tel Aviv museum to wade into community outreach. “We are an art museum, but like all other museums in the world, we have departments—and the design and architecture department is, in our case, somewhat obsessed with dealing with the current issues and questions of the field,” Vinitsky said.

Climate change and ongoing global conflicts have created the worst global refugee situation since World War II, with the UNHCR estimating that one out of every 113 humans on Earth were displaced in 2015. In the wake of so much upheaval, however, there has also been an influx of technology, of innovative concepts for temporary housing, and—as Vinitsky found herself eager to explore—a shift in international response to disaster relief. The traditional top-down model of outside organizations coming in is quickly giving way to a bottom-up model of locals leading recovery from within.

Vinitsky and her team spent the better part of two years in research and planning, focusing on four categories of bottom-up projects: those that share knowledge, those that offer social technology, those that are comprised of DIY processes, and storytelling.

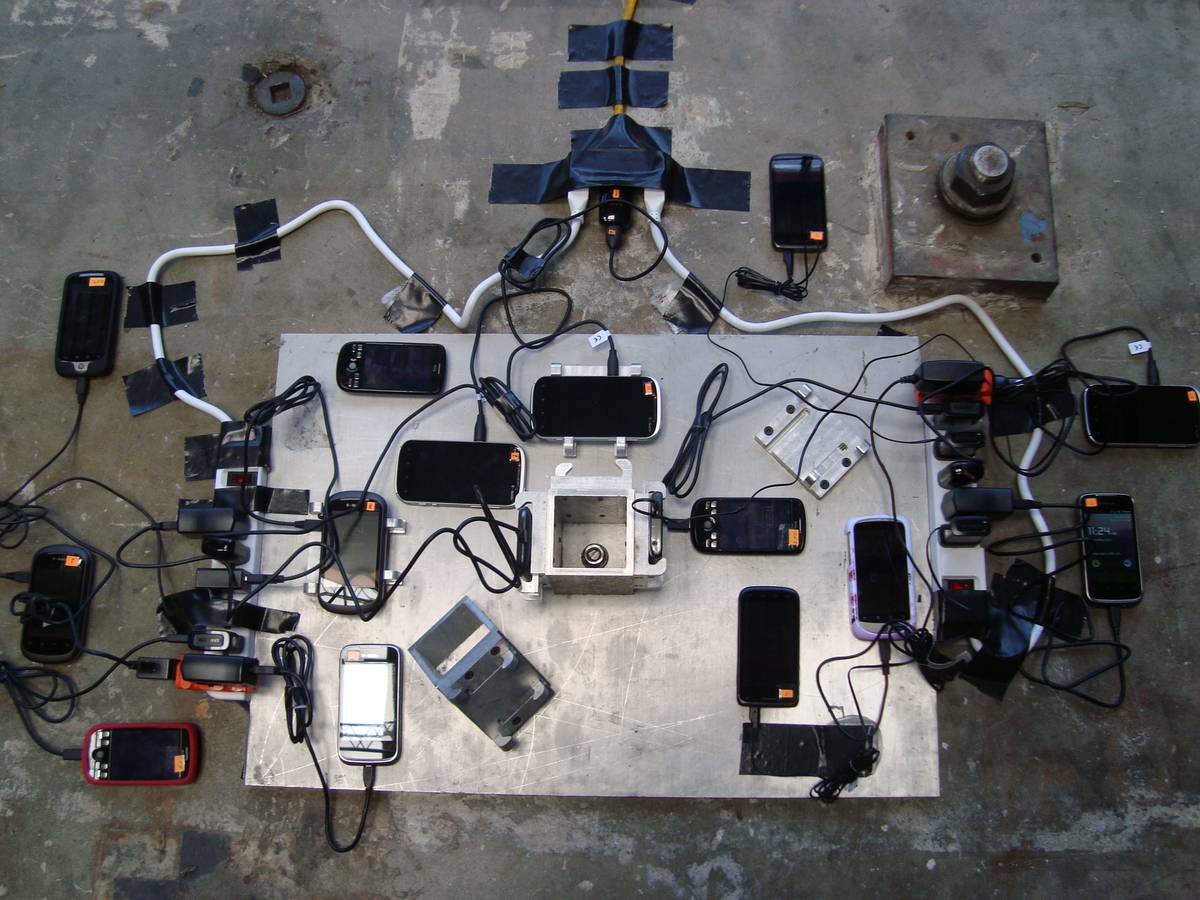

The result is an art exhibit without any art. Instead, artifacts on display include tweets about fallout zone locations; pages from first-aid instruction manuals, and a DIY shelter made of mud and recycled plastic. There are no “artists,” either: projects on display include those from Airbnb, which has a section explaining the history and execution of their Disaster Response Program, which allows neighbors to offer free shelter to those in need, IKEA, which in partnership with the UNHCR created a flatpack mobile refugee shelter (a model of which is on display for visitors) and MIT’s Urban Risk Laboratory. But the exhibit, which also includes a lecture series and a mobile site featuring links and tutorials to life-saving disaster response strategies, is being staged by the museum just like the Picassos and Kandinskys down the hall.

The physical exhibit was unveiled March 24 in conjunction with a mobile site and research project, summed up in a catalog that will be distributed internationally. It closes in September.

Despite its dark themes, Vinitsky hopes that the exhibit also offers a takeaway of optimism. “We didn’t set out to educate our visitors but to share common knowledge. People are much more activated today in how they see extreme situations. And if you have this knowledge, you know that you can help those who sit on the other side of the world.”

Debra Kamin is a Tel Aviv-based writer. Her work has been published in The New York Times, Variety, Foreign Policy and TheAtlantic.com.