The Bloody History of America’s Christian Identity Movement

In less than a year, two different attacks on Jews were inspired by a ‘Christian identity’ movement that fuses white nationalism and medieval anti-Semitism

Exactly six months apart, two different men were inspired to murder Jews by a “Christian identity” movement that combines white nationalism and medieval anti-Semitism.

Scholars, journalists, and activists who cover the far-right beat have long been aware of the centrality of the Christian identity movement to white nationalism in America. Yet the movement and its ties to contemporary anti-Semitism have remained largely unknown among the general public even as the violence it inspires has become an unavoidable reality.

Twice in the last year, armed American men have walked into synagogues and started shooting with the explicit intention of killing as many Jews as possible. And in both cases, the influence of the Christian identity movement in shaping their paranoid hatred was clear in the materials they shared on social media and the testimonies they left behind. As the tentacles of this peculiarly American racist-religious hybrid ideology are spreading, an examination of its historical roots and paranoid theology is overdue.

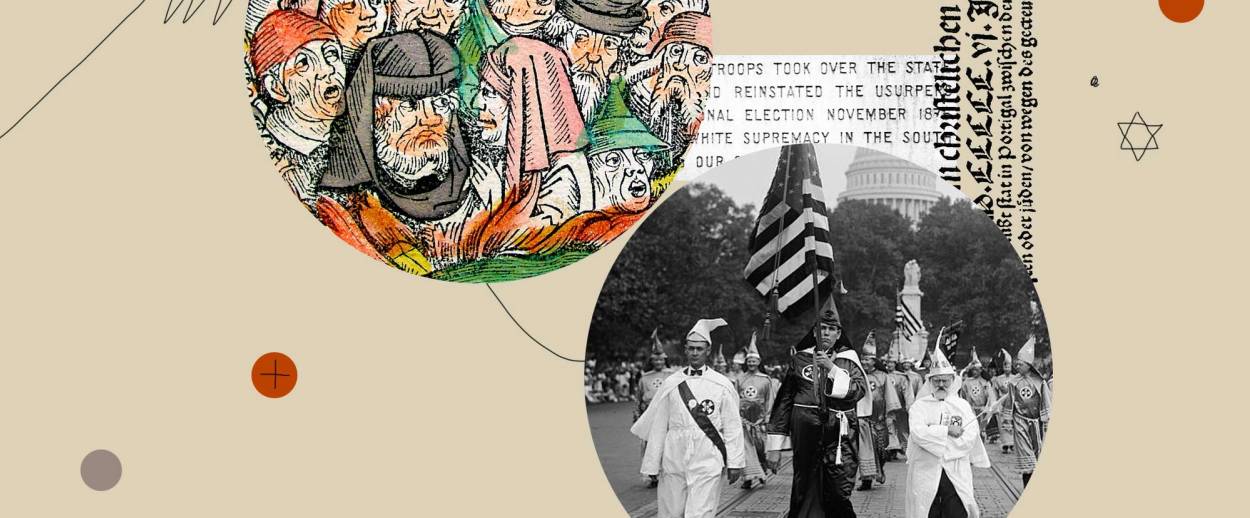

Christian identity grows out of a mystical form of Protestantism with roots in British religious movements of the 19th century. It reemerged in its American form in the mid-20th century led by people like California preacher and former Ku Klux Klan organizer Wesley Swift, who held that white “Caucasians,” not “Asiatic” Jews, were in fact the true descendants of the 10 tribes of Israel. Christian identity commanded a small, but dedicated following at its height in the 1950s. Swift was able to draw audiences in the thousands and drew from the same religious zeal in the greater Los Angeles area that had made radio preacher Aimee Semple McPherson one of the most popular ministers in the United States in the 1920s and 1930s and gave rise to such unorthodox spiritual movements as theosophy and Scientology.

Since its emergence in America, Christian identity theology has been tied to dozens of white nationalist terrorist attacks over the past 50 years, including the 1968 bombing of a synagogue in Meridian, Mississippi, and the murder of Jewish radio personality Alan Berg in Denver in 1984. And most recently it shaped the delusional thinking of the killer who murdered 11 congregants at the Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh, and the 19-year-old killer he inspired who walked into a Chabad in Poway, California, six months to the day after the Pittsburgh attack, and murdered 60-year-old Lori Gilbert-Kaye. Clearly, the ideology of Christian identity is a key conduit for violent anti-Semitism in America but the problem is larger than one extremist faction.

The Poway shooter, John Earnest, was a churchgoer but he did not belong to a Christian identity sect. He was a member of the Orthodox Presbyterian Church, founded by fundamentalist Presbyterians opposed to the spread of modernist theology in the mainline Protestant churches in the 1920s and 1930s. Fundamentalist denominations like the Orthodox Presbyterians uphold the literalness and inerrancy of the Bible, rejecting modernist doctrines that treat the Bible as a literary and historical document as well as a religious text. Evangelical pastors have denounced Earnest’s actions, but some have acknowledged being unnerved by the 19-year-old’s “frighteningly clear articulation of Christian theology.”

The manifesto left behind by the Poway shooter reads like a hybrid of classical Christian anti-Semitism and contemporary white nationalism. He alternated within paragraphs—sometimes within sentences—from charging the Jews with responsibility for the death of Jesus and the early Christian saints to declaring that Jews “[fund] politicians and organizations who use mass immigration to displace the European race.” The document is riddled with contradictions and is inarticulate even by white nationalist manifesto standards, as it moves between citing the Gospels and the killer’s love of Frédéric Chopin with explosive hatred toward Jews. But what it does evince clearly is a grounding in a form of anti-Semitism that’s equally in debt to older Christian traditions and more modern secular variants centered on race and soil. The document and the murderous violence it accompanied show that on the fringes of the white nationalist right, disparate and even seemingly incompatible traditions of anti-Semitism can co-exist and merge into new hybrid forms.

The belief that Jews hope to flood America with immigrants and dramatically transform American society was commonplace in the 1930s and 1940s. Far-right crackpots like the Rev. Gerald L.K. Smith, William Dudley Pelley, and Elizabeth Dilling frequently made such claims. But so too did more “respectable” members of the right. Merwin K. Hart, the head of the National Economic Council, who maintained an extensive Rolodex of prominent industrialists who backed his organization, frequently wrote in his newsletter of the “alien” influences in the Roosevelt administration—personified by Jewish Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter—and his fierce opposition to admitting Jewish refugees into the United States. Hart even called for refugee visas to be restricted after the Anschluss in 1938, warning that the number of illegal Jewish immigrants was skyrocketing.

The broader concern of Hart and his allies in the “respectable” wing of anti-Semitism—liberal journalist Carey McWilliams called them the “armchair anti-Semites” of the right—was that liberal and socialist Jews were ultimately behind the hated New Deal and the corresponding transformations in American society. These armchair anti-Semites believed that admitting Holocaust survivors into the United States after World War II would be the first step in dismantling the Immigration Act of 1924 to preserve the racial character of America. American Jews, many of whom supported easing immigration restrictions broadly, were the bogeyman of the nativist right, and since right-wing nativists also often subscribed to Judeo-Bolshevik conspiracy theories, opposing immigration was a way to strike a blow against communism as well as Judaism and preserve the white Christian character of the United States.

The influence of classical Christian anti-Semitism, radical Christian identity anti-Semitism, and conservative nativism can be seen in our own time in the beliefs of the men who entered synagogues for the purpose of killing Jews. The Poway shooter cites Bible, chapter and verse, invokes a beleaguered white European civilization, and rails against “cultural Marxism,” which he blames on the Jews. But the depths of these sentiments transcend one shooter. After all, the sitting president of the United States is closely allied to the Christian right, warns of hordes of illegal immigrants swarming the U.S. border, and employed a staffer on his National Security Council who warned of the influence of “cultural Marxists.” And while the Pittsburgh and Poway shooters both condemned Donald Trump as a puppet of Jewish interests, their condemnations do not negate the continuities between their belief systems.

In 1946, at the same time as Wesley Swift preached his gospel of hate in Southern California, Fortune magazine found in a national poll that anti-Semitism correlated with a variety of beliefs then common on the right—extreme anti-communism, isolationism, hostility to organized labor, and opposition to the New Deal welfare state. Swift’s closest political ally was none other than Gerald L.K. Smith, one of the most prominent anti-Semitic activists in the country, who loudly proclaimed his opposition to the moderates and “internationalists” who controlled both political parties. Smith was never a mainstream figure—he won less than 2,000 votes in his third-party 1944 bid for the presidency—but Smith, Swift, and the Christian identity movement represented the radical edge of the right in the 1940s and 1950s. And while the Christian identity movement today remains small, its ideas continue to exert an outsize impact on the American right.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

David A. Walsh is a PhD candidate at Princeton University. His dissertation is on the far right and the origins of the conservative movement. He has written for a number of different publications, including the Guardian, the Washington Post, and the Washington Monthly.