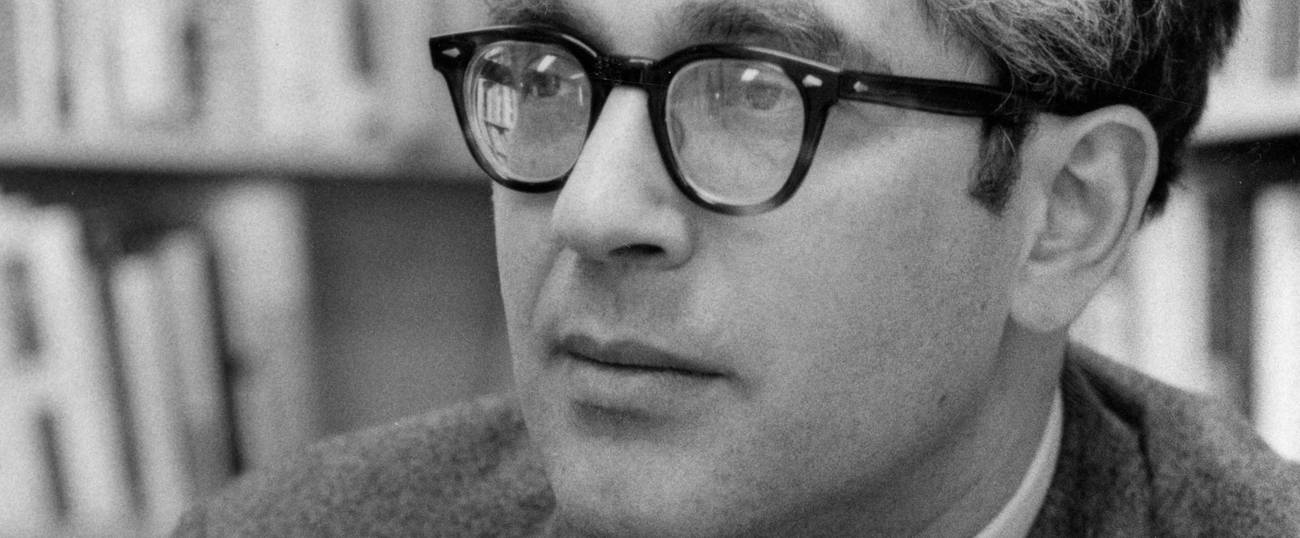

The Immortal Mind of Nathan Glazer

‘Nat’ to his friends, Glazer, who died Saturday at 95, was among the last of the original New York intellectuals and a remarkable thinker who never lost touch with how ideas affected real people’s lives

Nathan Glazer died this past Saturday at 95: one of the last surviving members of New York intellectuals who graduated from the tenements to the revolutionary excitement of City College and the life of the mind, and from there to the world stage. Glazer was a professor of sociology at Berkeley and then Harvard; the co-editor of the most influential journal of public policy in the second half of the 20th century; and the co-author of two of the most important books of popular sociology in that same period. To his friends, he was Nat, and admired as much for his modesty and humane sensibility as well his brilliance. To friends like me, who worked with him in the realm of ideas, he was admired for something even rarer: He merged his humanity with his intellect, and so made ideas matter for real life.

Since 1959, I’ve been what you might call an intellectual entrepreneur: someone who, while not quite a grade A intellectual himself, gathered disparate thinkers, polished their ideas, and pushed them into the public sphere. In that time, no thinker in America has justified my belief in the practical impact of ideas, and their value to our society, so much as Nat did.

Nat was an intellectual par excellence, but he was also a boy from the Bronx: the son of a Yiddish émigré sewing-machine operator, a street kid who never lost that sensibility. And he applied his intellect to something very sensible, very real, indeed: how normal people lived; how they felt about their surroundings; how they used their values to make choices; and how policy might be shaped to help them improve their lives in the least intrusive, most empowering ways.

I knew Nat, first through his writing, then as a fellow teacher at Harvard, then as a writer for the magazine I published, The New Republic, and, over time, as a friend. His death has shaken me—because, even at 95 (and he was lucid until the end) his was an example of the habit of thought we need to cultivate, if we’re to navigate a trying American epoch. In a period of unseen complexity that’s being answered by thin, reactive ideas on both sides of our public divide, Nat’s legacy is vital for resuscitating a discourse protean and imaginative enough to solve our problems. What’s more, Nat’s intense, lifelong focus was on America’s deepest, most personal divide: the question of identity, and the ways to bridge it.

***

The first time I encountered Nat was in 1959, when I was a graduate student at Harvard, in the pages of a book he’d co-authored nine years before. The book was called The Lonely Crowd: A Study of the Changing American Character, its primary author was Harvard sociologist David Riesman, and, when I read it, it was the most popular book of sociology in American history.

The guiding assumption of the book was deceptively simple: Fifty years into the 20th century, America was starting to change in ways nobody had imagined. People were moving away from small towns and family ties—the old bourgeois structures— and going to cities and then suburbs: They were buying more, spending more, traveling more. Corporations were growing to cater to their tastes: music, movies, lipstick, cars. Government was expanding to meet their needs: interstates, the GI Bill, home-ownership loans. Writ large, a sea change was underway: Consumer capitalism and mass democracy, fresh off their victory over fascism, were on the move and reshaping the country.

David’s and Nat’s question about this reshaping was also deceptively simple: How would it affect the identities of the Americans experiencing it? Their answer, based on methodological research—interviews, analysis—was double-sided. Modern, mobile, consumer society allowed these people more freedom and created more anxiety, provided more choice and ensured less confidence about how to choose, rendered them more liberated and more lonely—which made them more likely to behave not as real individuals but as members of a crowd.

I was 20 when I read The Lonely Crowd, and part of it enlightened me while the other part bothered me. Clearly, something new was happening in America, as Riesman and Glazer described, but their findings didn’t seem to account for another America I knew, from growing up the son of Yiddish immigrants in the Bronx—a tribal America, where ethnic culture bound people more than commodities. That America was real to me, and it seemed to me that The Lonely Crowd ignored it. In a way this elision made sense: After all, Riesman was born to Philadelphia Jewish elites, who, as David himself told me, mobilized against further “ethnic” Jewish migration to the city—and against Zionism as well.

I think Nat must’ve agreed, because 13 years after he wrote The Lonely Crowd, he partnered with a very different sociologist to write what I’ve always seen as a complement to that earlier opus. The book was Beyond the Melting Pot: The Negroes, Puerto Ricans, Jews, Italians, and Irish of New York City, and the co-author was Pat Moynihan, an Irish-American boy from Manhattan. Unlike David, both Nat and Pat came up in ethnic enclaves, they knew in their bones that ethnicity mattered more than anyone was saying it did, and they decided to use their intellectual training to figure out how.

Their findings, today, are commonplace, which is a testament to their enduring truth: The cluster of ethnic customs and vernaculars that a person was raised with followed her throughout her life; shaped not only her choices but her continuing focus on the community from which she came. For me, this validated on a scholarly level what I’d always sensed to be true. What’s more, it seemed to me like the exemplar of what ideas were supposed to do: help people make sense of their lives on the ground.

***

What did Nat’s focuses—the consumer market, the democratic state, the immigrant heritage—mean for the policies he decided to support?

I didn’t know him in those days, but I’ve always believed they led to his growing disillusionment with the Great Society and the postwar liberal project. In a country where multiple cultural groups came up against consumer economics and a politics of crowds, talking about an overarching “ideal,” like ending poverty, seemed increasingly absurd. Groups were too complicated for that—they’d respond to policy in too many different, unpredictable ways. Liberalism couldn’t, in a society this complex, be an “end”: It had to be an end to the idea that an end, any ultimate resolution, exists; a commitment to particular and incremental fixes; to the reality that history, and the work of being human together, is a circle that never closes. Thinking about it any other way was courting blindness—and backlash.

I met Nat around when he started to give these ideas a public forum. Two friends of his from his days at City College, Daniel Bell and Irving Kristol, had founded a journal called The Public Interest to offer what they saw as more complex, varied, imaginative, liberal solutions than those supplied by the left or right. In the mid-’70s, we started teaching a course on The Lonely Crowd together—me supplying the pizazz for the undergrads, Nat the bottom-line intellect. Around this time, he joined The Public Interest.

This was also when I bought The New Republic, which shared certain aims with The Public Interest. I’d come up on the Jewish left, pushed further that way over Vietnam, grown horrified at the movement’s simplistic oppressor-oppressed dichotomy, and moved toward the liberal center. I was already active in Democratic politics, and I ran The New Republic with a political-intellectual aim: to use ideas to pull the McGovern Democrats back my way.

Being a centrist, a liberal, wasn’t a comfortable position to be in during the 1980s and 1990s: The left thought we were sellouts, the right that we were namby-pamby. But I think it was a successful position, at least for awhile. With the Clinton-Gore Democrats, we got a lot of what we wanted: a focus on gay rights; more money for AIDs prevention; more humanitarian intervention (a concern for me); a reasonable welfare reform bill in a heavily Republican Congress (a concern for Nat).

In other ways the Clinton-Gore apex was a disappointment. The passage of DOMA, with Clinton’s support, was a blow for me. For Nat, the blow was the increasingly hard-line mentality of his old allies: Irving Kristol and his powerful political supporters. Unlike Nat, Irving saw The Lonely Crowd’s consumer society as both toxic and reversible, and he looked first to government-sanctioned traditional morality, then to great military works abroad, as the ways to reverse it. This was the origin of the neoconservative movement, and it’s what drove Nat, Dan Bell, and others associated with The Public Interest, such as Mark Lilla, away from the journal, and, often, to The New Republic.

In 2009, when Irving died, Nat summed up the difference between them in his typically calm, lucid way in our pages:

Irving … noted that “bourgeois society was living off the accumulated moral capital of traditional religion and traditional moral philosophy, and that once this capital was depleted, bourgeois society would find its legitimacy ever more questionable.” And so his tolerance and sympathy for religion, the more orthodox and traditional the better. That was questionable, and rubbed many (including me) the wrong way. In the latter days of The Public Interest, there were too many articles on how public policy could help promote marriage and stem the decline of the traditional family. Following the disciplinary tendencies of most sociologists, who simply project an ongoing change into the future, I thought neither traditional religion nor the family could resist the onslaught of commercial society.

Nat believed social forces couldn’t be reversed, only compromised with; and he also didn’t believe commercial society and its freedoms were such a bad thing. After all, some people measured themselves by what they could buy, but others measured themselves by family ties or ethnicity, because human beings are infinitely varied. I agreed with that—I only wish I could’ve stated my disagreement as clearly and cleanly as Nat did.

But Nat wasn’t just a clear thinker; his clarity gave him the capacity for real courage: He would arrive at a position, interrogate it, and stick to it calmly and firmly, unless further investigation and reflection made him change his mind. Never was this more obvious to me than in his most public break with Irving and the Public Interest position, in the pages of The New Republic, on the most divisive issue of the period: affirmative action.

***

Since the 1970s, Nat, like me, had been a skeptic of affirmative action, based on liberal principles: In a 1975 book, Affirmative Discrimination, he argued that imposing categories on complex inheritances would only lead to the kind of group separation that Civil Rights was designed to transcend.

But 23 years later, with the black community grappling with inner city poverty and crime, Nat changed his mind: Ideally, every person should be treated as an individual, but group history was clearly a reality that couldn’t be so easily transcended. Therefore a compromise had to be reached. This is what he wrote for the magazine:

Preference is no final answer (just as the elimination of preference is no final answer). It is rather what is necessary to respond to the reality that, for some years to come, yes, we are still two nations, and both nations must participate in the society to some reasonable degree. Fortunately, those two nations, by and large, want to become more united. The United States is not Canada or Bosnia, Lebanon or Malaysia. But, for the foreseeable future, the strict use of certain generally reasonable tests as a benchmark criterion for admissions would mean the de facto exclusion of one of the two nations from a key institutional system of the society, higher education. Higher education’s governing principle is qualification—merit. Should it make room for another and quite different principle, equal participation? The latter should never become dominant. Racial proportional representation would be a disaster. But basically the answer is yes—the principle of equal participation can and should be given some role. This decision has costs. But the alternative is too grim to contemplate.

Three points are worth making about this piece.

First, it took real courage to make this break. Much as hard leftists today accuse people who express patriotic tendencies of psychological blindness, neoconservatives then accused Nat of another character flaw, lack of “courage.” Like the positionalist left, they wouldn’t grapple with his change of mind on its own terms, which were liberal.

Second, these liberal terms of Nat’s are important to understand, because Nat’s liberalism always took its cues from the complexities of real life, where values were multiple. In the case of affirmative action, Nat was arguing that two values, merit and equality, had to be held in tension: Both were too important to the functioning of society to be let go. In this, as in all things, he was a pragmatist, and a person of the vital center, who believes that competing values had to be accommodated to ensure a healthy polity.

Third, two decades on, Nat’s flexibility looks doubly prescient, because the social fractures he noted in the black community have migrated, not simply plunging a social group into misery (which is bad enough) but helping elect a president. The white underclass is foundering: deluged by a market that sells self-esteem and instant gratification and high expectations; struggling to cope with an increasingly diverse society whose identity categories seem to exclude them; and lacking the comfortable scripts of the upper-middle class or the aspirational scripts of immigrants to steer them clear. Among this cohort, drugs, guns, shootings, and suicides are on the rise, making an obvious audience for charismatic reactionaries like Donald Trump.

We have to figure out a way to fix this problem. Partly this is a moral imperative, a dictate of simple compassion. Partly it’s pragmatic, because the fact that a sizable minority of Americans are experiencing protracted breakdown can only be bad for our collective life. If Nat would’ve had time for another book, I wish this is the one he’d have written—a sequel of sorts to The Lonely Crowd—because we badly need his guidance today.

***

But we don’t have Nat anymore. What we have are the lessons of a life—and what survives are both the ideas and the courage it took to stand behind them.

Nat, more than any thinker I know, cared about reality—how people felt about how they lived. He mentioned, a few years ago, that he wished he’d have made time to write novels, and this makes sense, because he was above all a humanist: a person whose complexity of thought derived from the complexity of daily life and the reality of human limits. Indeed, the nicest thing Nat ever said to me is that I taught him a lot about teaching a class: He loved how I drew out the students, provoked them, went about it all with a twinkle in my eye. I was a young man then, and it was stunning to get this kind of compliment from him. But, looking back, it’s of a piece with who he was: a person whose self-knowledge let him appreciate the strengths of others, and who brought that realism to the intellectual work he did.

We don’t live in Nat’s times—he recently mentioned, with the good-humored clarity he’d so ingrained, that we were not one but two generations removed from them. But, unlike history, habits of thought can be replicated. That’s where Nat comes in. To many of us who hope the life of the mind can help us see a little clearer around the collective bend, he is our guiding star

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Martin Peretz was Editor-in-Chief of The New Republic for 36 years and taught social theory at Harvard University for nearly half a century.