Nyets

On the eve of yet another Super Bowl without his beloved New York Jets, a lifetime fan sees echoes of Judaism in his tortuous loyalty

One of the most poignant images in Jewish iconography is of Moses, standing on Mount Nebo looking across the Jordan River into the Promised Land—a place he understands he will tragically never be allowed to enter. It’s an image I’ve come to fully understand after a lifetime not only as a Jew but also, maybe even more relevantly, as a fan.

All my life, I have been both a Jets loyalist and a proud, practicing Jew. I owe my religious commitment to Judaism to my parents and grandparents and their deep-rooted belief in the importance of Jewish education, prayer, and service to the community. But I place blame for my lifelong dedication to the Jets squarely in the laps of my father and grandfather. Apparently, in my family at least, dedication to a seemingly futile team is one of the riches of patrilineal descent.

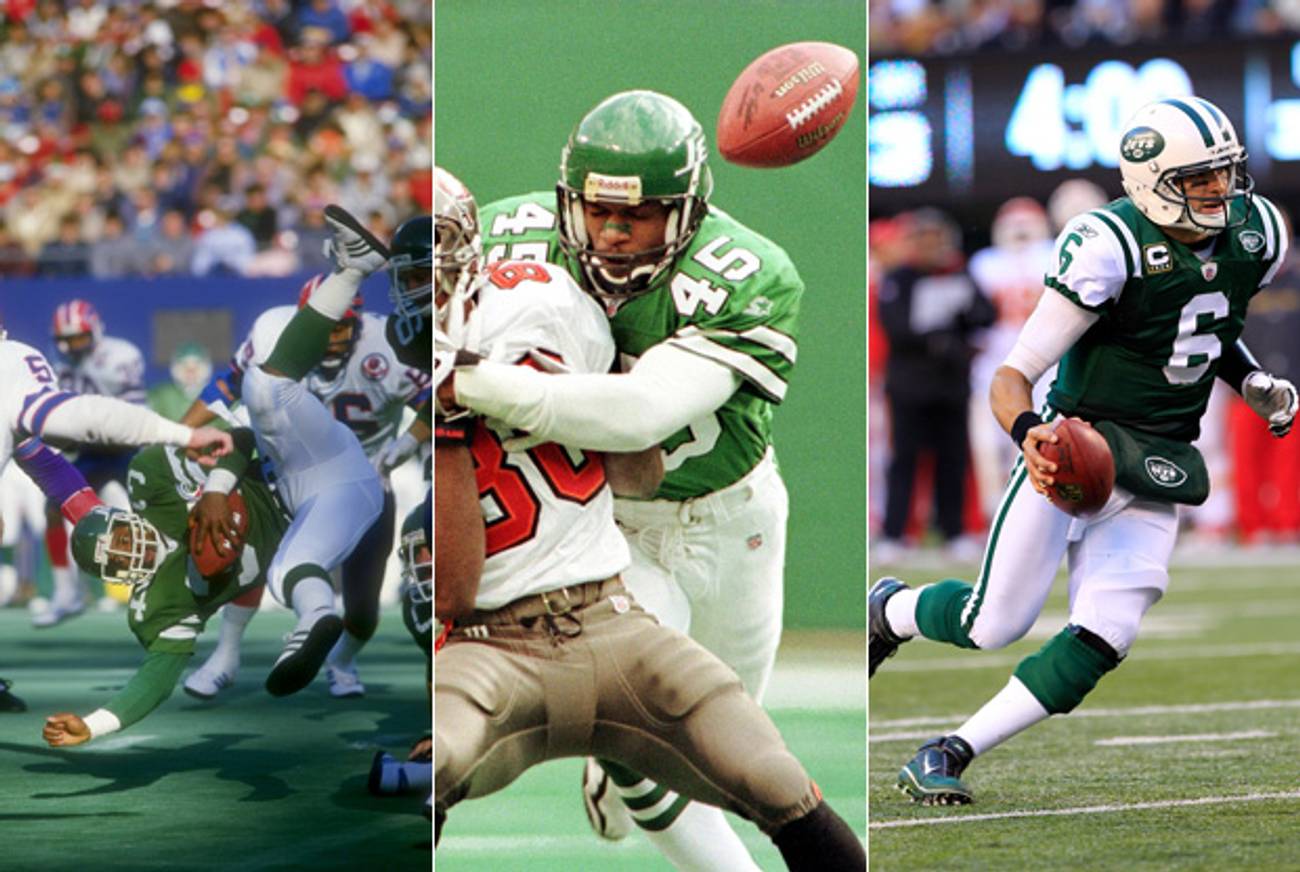

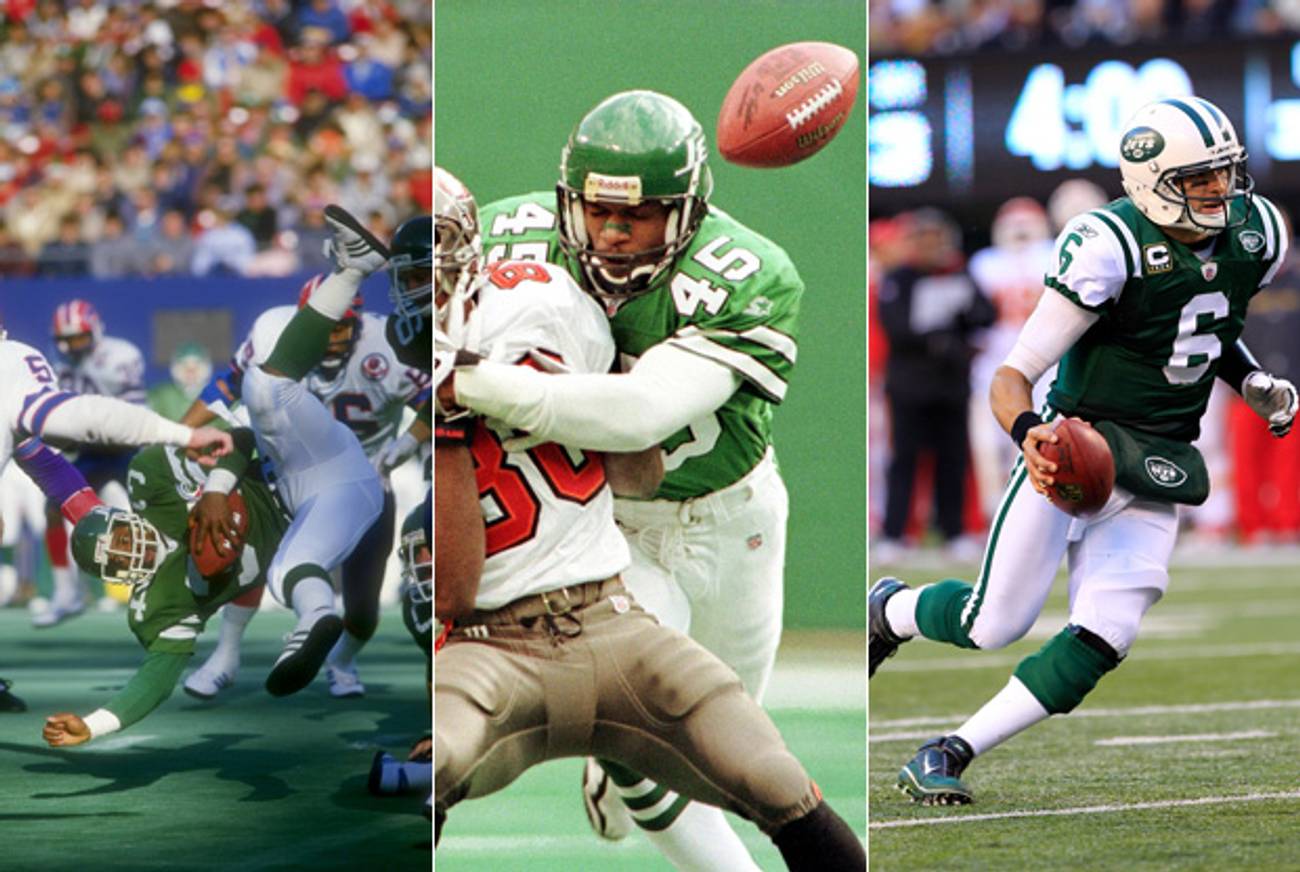

As I’ve grown up, if anything my emotional investment has outgrown theirs. And yet, the misery has worsened. Indeed, I’ve come to see the Jewish psyche as a perfect fit for the Jets, from the fan base and the tradition of loss to the psychological syndromes and the community infighting. Like the Jews, the Jets have been through exile and endured life as second-class citizens. The team forced the fans to make a choice by scheduling a game against the hated New England Patriots on Rosh Hashanah and another starting an hour before Yom Kippur. And though in my life, they’ve been one game shy of returning to the Promised Land four different times, the Jets have—just like Moses—never managed to cross the frontier into the Promised Land.

On the eve of this year’s Super Bowl, the Jets’ misery is more pronounced as their two fiercest rivals prepare to play on the biggest stage for a combined 12th time since the Jets’ sole appearance. And I am forced to root for the archrival Giants.

****

Like many American Jews, my parents grew up in Brooklyn as Dodgers fans. As the Dodgers found a way to lose each year, my father’s disdain for the New York Yankees—who kept finding ways to win seemingly every year—grew to the point where he couldn’t stand anything affiliated with them, including the football team that also played in Yankee Stadium: the New York Giants.

My father finally got his football team in 1960, with the creation of the New York Titans, a team that even carried a Jewish chip on its shoulder: Their name derived precisely from their ambition to be bigger than the Giants. In 1963, the Titans were bought by Jewish entertainment mogul David Abraham “Sonny” Werblin and renamed the Jets—thus ushering in what seemed to possibly be a genuine redemption.

Werblin took a gamble and signed the upstart quarterback Joe Namath to lead the team. In 1969, just three years before I was born, the Jets made it to the Super Bowl, where they faced the heavily favored Baltimore Colts. My father was in law school at the time, but he skipped out on studying for his final in order to watch the game. The Jets pulled an upset of Maccabean proportions, and my father passed his exam.

But the Jets have never been back to the Super Bowl—and I’ve been left to half-wonder if this isn’t because my father made some deal with the devil: Just let the Jets win this one time and just let me pass this test, and I won’t bother you about this ever again.

After a few exoduses from Polo Grounds and Shea Stadium, the Jets moved to the Meadowlands in 1984—where they would be second-class citizens at Giants Stadium, which they shared with that other New York football team. The Meadowlands was not far from my parents’ home in New Jersey and, every week that the Jets played at home, my father took me to the game. We’d sit with the same group of fans, our ritual minyan witnessing the Jets regularly sacrifice wins in creative ways.

The Jets spent years breaking our hearts. They picked awful coaches and drafted disappointing players. Same Old Jets was not only their motto, but the answer to our near-Talmudic inquiry: Why?

For my family, it might as well as been l’dor v’dor. And for many fans, including me, our biggest enemies often weren’t the division rivals or their players, but the Jets themselves and their coaching staff with their conservative, maddening, and predictable play-calling. Despite it all, we dutifully kept the faith, hoping our loyalty would be rewarded. On several occasions, I went to Shabbat services in the morning before walking nine miles from my parents’ house in Teaneck to the Meadowlands to see some critical late-December game (which of course the Jets usually lost).

I rarely missed a game—until I went to college at Cornell, where the Buffalo Bills overshadowed the Jets. Trying to see a Jets game at Cornell was like trying to be an observant Jew in an area with no synagogue; I was on my own. And each week, the futility of my Jets loyalty was laid bare, since my college years coincided with the Bills making the Super Bowl four years in a row. Even one would have been enough. Dayenu.

Like my father, I eventually went to law school. But instead of watching the Jets win the Super Bowl—or even get there—as he did in law school, I was rewarded with therapy. During my third year of law school, the New York Daily News held a contest for long-suffering Jets fans to attend a session of group therapy. The Jets were on their way to a 1-15 season. My friends encouraged me to apply, and no one was surprised when I was chosen. The next thing I knew I was in a circle with 10 jets fans describing their various degrees of torture, leaving me to realize that while I wasn’t alone anymore, I was in company that even misery wouldn’t keep.

Not even therapy cured me. Each year my commitment grew deeper. But I did find a community of those afflicted. During the 2002 playoffs, I joined 70 other observant Jets fans for a Shabbaton of sorts, participating in Friday night and Saturday morning services and catered Sabbath meals. While the Jets beat the Colts 41-0, they lost again the following week. Same old Jets.

In 2010 and then 2011, the Jets returned to the football equivalent of Mount Nebo, 60 minutes away from the Super Bowl. And two years in a row, they met the fate of Moses. But unfortunately this year, unlike many Jewish empires and communities before them, the Jets’ faithful watched as their team was undone by infighting reminiscent of a synagogue board meeting gone bad.

Now I have a son of my own, who is 2 and a half and already knows the J-E-T-S chant. For Hanukkah this past year, I bought him a Jets uniform and helmet. But, like the Jets, he stopped suiting up after December.

Come September, just as we Jews are congregating for the High Holy Days, we Jets fans—of all different persuasions—will congregate at Met Life Stadium, hoping for a sweet new year. This year, 2012, I enter my 40th year of wandering. I still have hope. I’m not even asking the Jets to win a Super Bowl; just to get there. Next year in New Orleans. Dayenu.

Matthew Hiltzik (@hiltzikstrat) is the president and CEO of Hiltzik Strategies, a strategic communications and consulting firm. He is the producer of Paper Clips, Holyland Hardball, and Connected. He lives in New York City with his extremely patient and understanding wife and three children.

Matthew Hiltzik (@hiltzikstrat) is the president and CEO of Hiltzik Strategies, a strategic communications and consulting firm. He is the producer of Paper Clips, Holyland Hardball, and Connected. He lives in New York City with his extremely patient and understanding wife and three children.