Following a Dec 12, 2018 ruling by a Ukrainian district court which found two Ukrainian officials broke the law by interfering in America elections, Tablet is reprinting this 2017 interview with one of the officials in question, MP Serhiy Leshchenko.

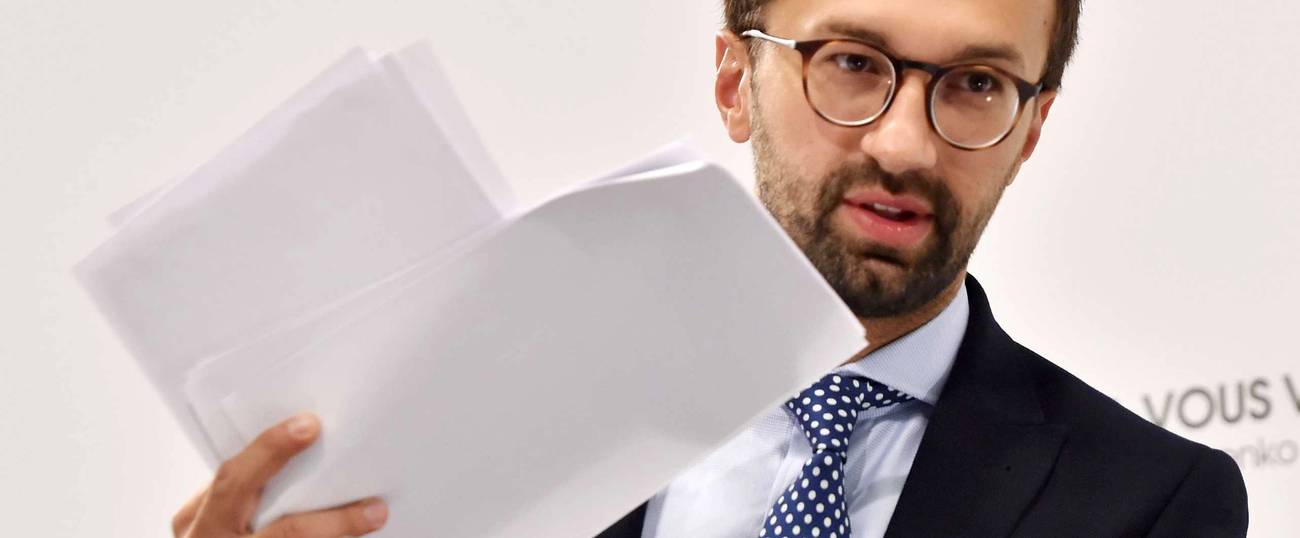

Serhiy Leshchenko, the Ukrainian MP who leaked evidence of Paul Manafort’s systematic corruption to The New York Times, kicking off the latest round of Trump-Russia scandals, is a former investigative journalist famed for his pedantic and forensic habits in parliament. In his mid-30s, he is very tall and rail thin, and dresses in the mod-ish slim-cut suits and skinny ties that one can only pull off if one has been blessed with the lithe frame of an indie-band member (except his tastes run to house music). Over a genial smile, the young MP sports a full face of stubble and wears the black thick-framed glasses that are a universal tribal marker from Shoreditch, London, to Williamsburg, Brooklyn, as well as more exotic outposts in Tokyo and Buenos Aries. He resembles a managing partner in a cutting-edge Scandinavian architecture firm devoted to turning skyscrapers into greenhouses.

Leshchenko and some of his journalist reformer friends, such as Mustafa Nayem, were brought into Ukraine’s parliament by President Petro Poroshenko on his winning parliamentary slate in 2014 as a way of showcasing his reformist credentials. Leshchenko has since become a fierce critic of Poroshenko, whose parliamentary faction he has never left. He and his friends are principled activists who are opposed to the corruption that is endemic at the highest levels of Ukrainian governance, but they are now also politicians. Feted by the international media, they now find themselves balancing on a precipice between their anti-corruption activism and their responsibilities as lawmakers who represent the Ukrainian state.

Last autumn, Leshchenko’s reputation was threatened when it appeared he had unethically borrowed money to buy an apartment in the middle of Kiev from his friend and former boss, the editor of Ukrainian Pravda. The accusation was that he had received an illicit gift in the form of a favorable rate for the apartment. A partisan of extreme transparency, he had gone after many politicians, civil servants and government functionaries for their corrupt practices, so even the slightest implication of impropriety filled his many enemies and opponents with undisguised glee. In March, the court found him to be innocent and he was cleared of charges.

Over the course of the last year, Leshchenko has also become a central figure in revelations relating to the scandals surrounding former Trump campaign head Paul Manafort and the myriad connections between Moscow, Kiev, and the embattled Trump administration. For his part, Manafort denies that the leaked evidence was authentic, and argues that Leshchenko was trying to blackmail him.

I spoke to Leshchenko at the sidelines of parliamentary hearings, and Leshchenko would interrupt our conversation to run into the presidium hall to vote when individual votes were called. What follows is an edited and abbreviated version of our conversation.

So, is contemporary Ukraine—in its current form, as it is now constituted—a liberal democracy, or is it not?

Ukraine today is a country that is on the way, it is on the path. It has exited the stage of totalitarianism but has not arrived fully toward democracy yet. We have all the institutions of a democracy, but they do not always function fully yet like they do in a normal European country.

You are no longer just a muckraking journalist. You are an NGO guy, you are a politician, a policymaker, an activist, a lawmaker. There seems to be an inherent contradiction between your activist position, which you carry on as a guy who came out of journalism—you are still getting documents out, you are still getting them to the public. But now you are also a politician, right? So you wear several hats and many people, even people who like you very much and support you, often think there is a contradiction possible between your various roles. Do you see any contradiction?

No. I think that is too simplistic a formulation, to assume that a politician should just sit quietly in parliament and vote silently on passing laws. In the modern world, you have your own President Trump: Is he a Twitter blogger or is he rather a president?

He is probably more like a Twitter blogger.

Well, OK, see? We have hybrid forms in everything, and there is no longer a “pure form of journalism,” and therefore we have a flattening of the vertical into one in which every active Facebook blogger believes that he is actually exactly the same as a Pulitzer Prize-winning professional. And today the post of a Facebook blogger can have more influence on social processes than an article written in a respected publication. In the same way, there is a mixing of hybrid forms in politics, and there are no stereotypes of the sort that were characteristic of the 1970s, for example.

The main thing that I try to do is to form the policy of the country. To make sure that this society develops zero tolerance for corruption, a toxic attitude toward politicians and corrupt officials. This can be achieved using all the tools that I have in my hands. That is why I am a politician, not a traditional deputy who is a passive, gray, inconspicuous biomass that lives purely by the orders of its political leader. I am proud to say that I can boast of many achievements, both in terms of passing laws and in protecting specific initiatives and also specific citizens who were victims of the tyranny of state machinery.

Let’s return to Paul Manafort. There is a nagging issue that never becomes apparent in all the various articles that have been written about the scandal, including both the Politico and New York Times pieces. You are leaking documents that you have from your sources. You are the essential guy in Ukraine in making sure that we in the West know about Mr. Manafort and his many charming adventures in Ukraine. So, when you leak, are you representing yourself as an independent-minded reformist MP, or are you executing government policy?

No, I am representing only myself, of course. I never ask permission from anyone, not the president, not the Rada. This is purely my own position as a politician.

So no one else is involved officially in these leaks? Not the SBU (Ukrainian Security Services), not the prime minister, not the NABU (National Anti-Corruption Bureau)? No one else is involved here? You have your source, and you are totally independent on this issue, just you? This is not government policy?

Of course. I never speak with them or coordinate my position on either Manafort or any other issue. I am not authorized to comment on the government’s position, but I did not coordinate my speeches with anyone.

I see. Please explain the connection between this and the August scandal. What is the new information that has come out now, and how is it substantially different from what we already knew about Manafort’s activities?

The issue is that in August, excerpts from the so-called shadow accounting were published, a manuscript ledger that people from the Party of Regions [the now-disbanded party of former President Viktor Yanukovych] conducted on their expenses. And in this manuscript book, they simply noted the amounts that were allocated for specific bribes and kickbacks to officials, for illegal financing of positive coverage on TV, but there was no actual documentary confirmation of this black/shadow accounting.

Now what I have is documentary confirmation of that accounting compiled in the shadow-accounts department of the Party of Regions. The evidence of the payments shows that, as we always surmised, Manafort received money to an account in America, but he did not receive it directly from the Party of Regions. We now know that he received the money from an offshore company in Belize, which was tied to accounts in Kyrgyzstan. With this account in Kyrgyzstan, money was transferred to his main account in America, in U.S. dollars, through a correspondent account in Commerce Bank. Therefore, it all must be investigated by the FBI, because the FBI can get access to Manafort’s bank records in America, interrogate him in America, and request confirmation of this payment, and so on.

OK. Do you want him to return here for questioning?

For Ukraine, it is important to investigate that episode, since it is associated with other murky actions taken by the Party of Regions, which include the shadow accounting. In fact, this is the first and only time when any corrupt payment by the Party of Regions has been confirmed by documentation.

As far as I know, the Prosecutor General’s Office, which is conducting an investigation, along with the Department of Investigation of Crimes against the Maidan, sent a number of interrogation orders to the FBI that have been ignored in America. This applies to the Skadden campaign [the Washington, D.C. law firm of Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom] which, commissioned by the Ministry of Justice of Ukraine, prepared a report related to the Tymoshenko case [former Ukrainian Prime Minister Yulia Tymoshenko was imprisoned in 2011; Skadden’s report found no political motivation in the prosecution]. And at the time, Manafort’s daughter was working at Skadden.

Where she sent you those love texts? [There were allegations that a purported cyberhack of Manafort’s daughter proved that Manafort was the victim of a blackmail attempt by Leshchenko.]

I have never spoken to her and never wrote anything to her.

As for that episode, the Prosecutor General’s Office sent requests for interrogations and they were not executed. I believe that the FBI should cooperate with the Ukrainian prosecutor’s office.

I think so, too. But I wrote an article at the end of March exploring the view held by many in Kiev that it was never entirely clear that Manafort was as important here as everyone is now saying, that there is evidence that he was much more of PR screen from the West.

He ran Yanukovych’s successful electoral campaigns four times: 2006, 2007, 2010 and 2012. And in these campaigns, he used political technologies that split Ukrainian society, but that helped Yanukovych win, and so he was the ideologist of the Yanukovych campaign.

Well, he was in the campaign, but does that mean that he had the greatest power over the ideological program?

Yanukovych listened to him, he had influence.

Tell me about the text messages and the allegations of blackmail.

I never wrote a single message to either Manafort or his daughter. I do not have any of their phones, no e-mail, no contacts with them over the social networks.

I do not know who faked those texts or for what purpose. But they were forged, they imitated my email. My mail is on the Gmail domain, and they made a mail account with much the same name on iCloud and sent messages from that account. It all began last year in August.

That was done in August before Manafort resigned? And it was done in an attempt to delegitimize your criticism? Do you think that the Ukrainian state took part in that effort?

It seems to me that it was almost immediately after he left the campaign, yes. I think that for whatever purpose it was done is now difficult to say, but I am ready to cooperate with the FBI if they want to investigate this situation.

But about Yanukovych and Manafort: He helped him win the elections, using superior sociological data, choosing special themes of political attack, choosing topics that split Ukrainian society in half. He created the image of Yanukovych as a candidate who would defend the interests of the Russian-speaking population, thus provoking a split in the society, as before that the topic of language had never been important.

So the big question—do you really think Manafort is a Russian agent?

Whether he is a Russian agent or not, I do not know. That should be investigated by the competent authorities. I know simply that first and foremost, he received funding from Yanukovych. It was dirty money, which was laundered by corrupt officials from our budget; this money was paid through illegal money-laundering schemes and fraud by electronic transfers through Khyrgiztan.

I believe that this investigation should be conducted in the U.S. and this is in the interest not only of America but also of the global fight against corruption, in the interests of Europe and Ukraine both, because the more exposure there is of Trump and Trump’s circle the more difficult it will be for Trump to conclude a separate deal with Putin, thereby selling out both Ukraine and the whole of Europe.

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.