Is the Women’s March Melting Down?

Millions of women mobilized against gender inequality and the election of Donald Trump in 2016. But only four of them ended up at the top—and the consequences have been enormous.

On Nov. 12, 2016, a group of seven women held a meeting in New York. They had never worked together before—in fact, most of them had never met—but they were brought together by what felt like the shared vision of an emerging mission.

There were effectively two different cohorts that day. The first one included Breanne Butler, Karen Waltuch, Vanessa Wruble and Mari Lynn Foulger—a fashion designer turned entrepreneur with a sideline in activist politics, who had assumed the nom de guerre Bob Bland. These four were new acquaintances who had connected in the days since Donald Trump’s election, through political networking on social media. Most of them had filtered through the Pantsuit Nation Facebook group, where a woman in Hawaii named Teresa Shook had days before floated the idea of a female-centered march to protest the incoming administration.

Soon after, Wruble—a Washington, D.C., native who founded OkayAfrica, a digital media platform dedicated to new African music, culture, and politics, with The Roots’ Questlove—reached out to a man she knew named Michael Skolnik. The subject of a New York Times profile the previous year as an “influencer” at the nexus of social activism and celebrity, Skolnik held a powerful though not easily defined role in the world of high-profile activist politics. “It’s very rare to have one person who everyone respects in entertainment, or in politics, or among the grass roots,” said Van Jones, in a 2015 New York Times piece. “But to have one person who’s respected by all three? There isn’t anyone but Michael Skolnik.”

When Wruble relayed her concern that the nascent women’s movement had to substantively include women of color, Skolnik told her he had just the women for her to meet: Carmen Perez and Tamika Mallory. These were recommendations Skolnik could vouch for personally. In effect, he was connecting Wruble to the leadership committee of his own nonprofit—a group called The Gathering for Justice, where he and Mallory sat on the board of directors, and Perez served as the executive director.

In an email to Tablet, Skolnik confirmed this account of the group’s origins. “A few days after the election, I was contacted by Vanessa Wruble, who I have known for many years, asking for help with The Women’s March and specifically with including women of color in leadership,” he wrote. “I recommended that she speak with Tamika Mallory and Carmen Perez, also who I have known for years.”

Linda Sarsour, another colleague from The Gathering for Justice network, was not present for these initial meetings but joined the Women’s March as a co-chair a short time later.

“There were other activists that I reached out to, who didn’t end up getting involved as prominently as those women,” Wruble told Tablet recently, adding that the primary goal for her at that point was clear, and simple: “I was very focused on making sure the voices of marginalized women were included in the leadership of whatever we were about to create.”

In advance of the meeting, Bland suggested they convene in Chelsea Market, an upscale food court in Manhattan. When the day arrived, the women managed to find each other but soon realized that there was nowhere in the hectic, maze-like hall of vendors quiet enough to sit and talk. Eventually, they retreated to the rooftop of a nearby hotel where, less than a week after the idea for a march sprouted, the seven women got acquainted.

According to several sources, it was there—in the first hours of the first meeting for what would become the Women’s March—that something happened that was so shameful to many of those who witnessed it, they chose to bury it like a family secret. Almost two years would pass before anyone present would speak about it.

It was there that, as the women were opening up about their backgrounds and personal investments in creating a resistance movement to Trump, Perez and Mallory allegedly first asserted that Jewish people bore a special collective responsibility as exploiters of black and brown people—and even, according to a close secondhand source, claimed that Jews were proven to have been leaders of the American slave trade. These are canards popularized by The Secret Relationship Between Blacks and Jews, a book published by Louis Farrakhan’s Nation of Islam—“the bible of the new anti-Semitism,” according to Henry Louis Gates Jr., who noted in 1992: “Among significant sectors of the black community, this brief has become a credo of a new philosophy of black self-affirmation.”

To this day, Mallory and Bland deny any such statements were ever uttered, either at the first meeting or at Mallory’s apartment. “There was a particular conversation around how white women had centered themselves—and also around the dynamics of racial justice and why it was essential that racial justice be a part of the women’s rights conversation,” remembered Bland. But she and Mallory insisted it never had anything to do with Jews. “Carmen and I were very clear at that [first] meeting that we would not take on roles as workers or staff, but that we had to be in a leadership position in order for us to engage in the march,” Mallory told Tablet, in an interview last week, adding that they had been particularly sensitive to the fact that they had been invited to the meeting by white women, and wanted to be sure they weren’t about to enter into an unfair arrangement. “Other than that, there was no particular conversation about Jewish women, or any particular group of people.”

Six of the seven women in attendance would not speak openly to Tablet about the meeting, but multiple sources with knowledge of what happened confirmed the story. Following an initial 30-minute phone call last week with Women’s March co-chairs Tamika Mallory and Bob Bland, Tablet submitted a detailed list of follow-up questions to the group by email and received a written response. Answers from both exchanges are quoted at length in this article.*

As its fame grew, so did the questions about the Women’s March’s origin story—including, at first privately within the inner circles of the organizations, questions pertaining to the possible anti-Jewish statement made at that very first meeting. And that wasn’t the only incident from the initial encounter that would have far-reaching consequences. Within a few months of the original marches, key figures who came from outside or stood apart from the inner circle of the Justice League, an initiative of The Gathering for Justice, left the organization. And many of those involved began questioning why it was that, among the many women of various backgrounds interested in being involved in the March’s earliest days, power had consolidated in the hands of leadership who all had previous ties to one another; who were all roughly the same age; who would praise a man who has argued that it’s women’s responsibility to dress modestly so as to avoid tempting men; and, at least in one case, who defended Bill Cosby as the victim of a conspiracy.

The questions started to be more practical, as well. At some point during that very first meeting in Chelsea, Perez suggested that the Justice League’s parent entity, The Gathering for Justice—where she, Mallory, and Skolnik all had roles—set up a “fiscal sponsorship” over the Women’s March to handle its finances. A fiscal sponsorship is a common arrangement in the nonprofit sector that allows more established organizations to finance newer ventures as they get off the ground and find their own funding. In this case, though, the standard logic didn’t apply since the Women’s March would, from its inception, raise vastly more money than its sponsor ever had. Over time, new details of the Women’s March’s organizational structure have been dragged into public view that reveal complicated financial arrangements, confusing even to experts.

Yet within no time, the March leaders would be named 2017 Women of the Year by Glamour magazine. There was a glossy book published with Condé Nast, a lucrative merchandise business selling branded Women’s March gear, and millions of dollars raised through individual donations and institutional funding from major organizations like Planned Parenthood and the powerful hospital workers union, 1199SEIU. Fortune magazine named Mallory, Linda Sarsour, Perez, and Bland to its list of the World’s Greatest Leaders, and New York Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand—in explaining why these four were on Time magazine’s list of the 100 Most Influential People—wrote: “The Women’s March was the most inspiring and transformational moment I’ve ever witnessed in politics … and it happened because four extraordinary women—Tamika Mallory, Bob Bland, Carmen Perez and Linda Sarsour—had the courage to take on something big, important and urgent, and never gave up.” In conclusion, the senator declared, “these women are the suffragists of our time.”

But in fact, according to many involved in the January 2017 marches, Gillibrand’s description wasn’t just over the top; it undermined and erased the very people actually doing the work to create female-centric voting blocs throughout the country. “To be fair, the Women’s March on Washington—the one I was involved with at the time—had no real connection to the many marches that took place across the country and globally that month,” said Wruble, in an interview with Tablet. “Local leaders, often first-time organizers, spearheaded marches in their own communities. Many used the branding we put out as open source and helped to make the marches look unified—which was certainly advantageous in creating the sense of a singular, massive movement—but they were the ones who did the real work.”

The Women’s March leaders have often dismissed their critics as right wing or driven by racism, but over the past two months their fiercest challengers have come from within their own shop—with women of color, and their own local organizers, often leading the pack. As of this article’s publication, numerous state chapters have broken off from the national organization—notably Houston, Washington, D.C., Alabama, Rhode Island, Florida, Portland, Illinois, Barcelona, Canada, and Women’s March GLOBAL.*

Mercy Morganfield, a longtime activist and daughter of blues legend Muddy Waters, has been one of the leading voices in calling for accountability from the co-chairs. For Morganfield, a former spokesperson for the Women’s March who also ran the D.C. branch, the various problems that people have had with the Women’s March—ideological, managerial, fiscal—should be seen as all of a piece. She recalled being startled earlier this year when Mallory—already a nationally recognized leader of the Women’s March—showed up at the Nation of Islam’s Saviours’ Day event. “When all of that went down, it was my last straw,” she told Tablet. “You are part of a national movement that is about the equality of women and you are sitting in the front row listening to a man say women belong in the kitchen and you’re nodding your head saying amen! I told them over and over again: It’s fine to be religious, but there is no place for religion in its radical forms inside of a national women’s movement with so many types of women. It spoke to their inexperience and inability to hold this at a national stage. That is judgment, and you can’t teach judgment.”

***

The development of the origins of the Women’s March and its transformation into a vehicle that promoted a small coterie of women—three of whom bizarrely professed their admiration for the openly anti-Semitic, homophobic, and misogynistic Nation of Islam preacher Louis Farrakhan—was a deliberate act, one that had nothing to do with the general spirit out of which the March was born.

On Nov. 8, Teresa Shook, a lawyer in Hawaii, created a private event page on Facebook calling for women to march on Washington the day after the presidential inauguration in opposition to Trump. “I was in Pantsuit Nation talking about marching,” Shook told Tablet, in a recent interview. “People were saying it’s not possible and that it was too soon and would be too cold, and so on. But then one woman said she would march, so I went off and created an event page for it. I went back into that thread and said OK I’ve created this event, here is the link and told people to share it.” She made it private, so the only way it would be seen was if friends invited other friends.

Shook woke up the next morning and found that her page had gone viral. Realizing it was far too much to handle on her own, she reached out to two of the strangers who had messaged her on Facebook: Evvie Harmon and Fontaine Pearson. “I picked people at random,” Shook said. “My message box was full. I had no time to vet anyone.”

Harmon, then a 33-year-old yoga teacher in South Carolina, had seen Shook’s call to action when her cousin sent her a Facebook invite to the page. She had some experience with mass mobilization from organizing her state’s efforts for the LGBT Join the Impact march in 2008. She made the first state page for Women’s March for South Carolina. Shook loved the idea and asked Harmon to help with making Facebook pages for all the states, and to start contacting anyone who had shown interest in taking over as local organizers. Harmon quickly became the co-global coordinator, along with Breanne Butler, a pastry chef based in New York.

At the same time, Bob Bland, owner of Manufacture NY—who claimed she had just raised money for Planned Parenthood based on the success of her “Nasty Women” T-shirts—connected with Pearson. (According to multiple sources, Pearson’s involvement eventually petered out. Efforts to reach her were unsuccessful.) Bland also connected with Vanessa Wruble via Pantsuit nation. Within a few days, that rooftop meeting was held in New York—which brought together Wruble and others with the activists from the Justice League, connected by Skolnik.

“In our first leadership meetings, we envisioned building the Women’s March as a flat structure with no one single leader, and inclusive of all voices,” Wruble recalled. “I was hoping through that, through working together, we could forge real relationships across different races, religions, and cultures. We could be the adults in the room after men—the patriarchy—had, quite frankly, completely screwed this country up.”

“From the very beginning, Vanessa [Wruble] was leading,” explained a source with direct knowledge of those early days. “She was the operational leader. She made sure all the people doing our various pieces were operating coherently. She walked people through all of the things that had happened, and then those that needed to happen. Some people were focused on logistics, some on community engagement, other people were working on the website—and she was the linchpin of it all, especially in the early days.”

For her part, Bland had her eyes on more outward-facing tasks. At some point, according to Shook, Bland asked her for access to her event page for the March. Soon after, Bland created a new page—designated as the official March page—and bought the womensmarch.com URL. Bland then deleted Shook’s original event page without asking, or even notifying, her.

Morganfield, the D.C.-based black activist, was one of the early Women’s March members. Morganfield had worked for ExxonMobil, Ernst & Young, and then—for nearly 20 years—at Pfizer pharmaceutical. In 2012, she was named the new D.C. state president for the American Association of Retired Persons, AARP. “I ended up working very closely with the national team,” Morganfield told Tablet. “I was on different national committees. I also would do things like pull together the buses to take people out to the NRA for the march and the rally. I was a big part of national.”

They don’t have a clue what they’re doing. They were chosen for optics—for the image they brought to the march.

At the same time, she saw from the start that there were serious issues brewing within the organization. Harmon began to share that view. Both said in interviews that, at this point, they were each contacted by Bland, who told them she had started butting heads with the co-chairs.

At the end of December, Harmon said she received a panicked call from Bland, who she said was calling to tell her that the co-chairs were suggesting they pay themselves 2 percent of all national funds raised. Morganfield said she also heard this at the time. According to one source who spoke with Tablet and who worked in close contact with Bland and the national team, $750,000 worth of merchandise was sold within the first couple of months before the march.

In an email to Tablet last week, Bland claimed she never said anything about the co-chairs asking to take any percentage of national funds.

Questions also began to emerge about the ideological values upon which the movement was being built. On Jan. 12, the Women’s March made public their Unity Principles, which asserted: “We must create a society in which women, in particular women—in particular Black women, Native women, poor women, immigrant women, Muslim women, and queer and trans women—are free and able to care for and nurture their families, however they are formed, in safe and healthy environments free from structural impediments.” Numerous observers noted the absence of “Jewish” from the list of signifiers, and began questioning whether it signaled something about whether and how warmly American Jews—the vast majority of whom vote and identify as Democrats—would be welcomed in a changing left.

In an email to Tablet the Women’s March wrote:

Women’s March models intersectional leadership through our organizing work, which includes 200 women who worked on the conveners table, 500 partners, 24 women involved in developing the Unity Principles—including some of the folks who are expressing concern now. They were part of the process then, and did not express the concerns they are noting today. Women’s March is greater than our small team of national staff and leadership, and we’ve never claimed their identities equal full representation of U.S. women.

But whatever concerns were popping up were ultimately no match for the steamroller of the event’s progress. And when the day came, the reality far exceeded expectations. Estimates for the March on Washington range between half a million and a million people, giving the city’s metro system its second busiest day in history. Estimates for all the Women’s Marches that took place in cities across the country, had between 3.6 and 4.6 million people participating. In terms of attendance and publicity, the event was an enormous, iconic success. It took the swirling, latent energy of the country’s broad political opposition to Trump and turned it into a dramatic showing of strength.

It also seemed to solidify four women—Mallory, Perez, Sarsour, and Bland—as the public face of what was, in reality, an amorphous movement. Multiple sources active at the time point to the media as part of the reason for this—with television cameras more drawn to the flash of fame than the tedium of logistics. “As we got closer to the march, the press piece was one thing that ended up outside of Vanessa [Wruble]’s purview,” noted a source with direct involvement at the time.

At the end of January, according to multiple sources, there was an official debriefing at Mallory’s apartment. In attendance were Mallory, Evvie Harmon, Breanne Butler, Vanessa Wruble, Cassady Fendlay, Carmen Perez and Linda Sarsour. They should have been basking in the afterglow of their massive success, but—according to Harmon—the air was thick with conflict. “We sat in that room for hours,” Harmon told Tablet recently. “Tamika told us that the problem was that there were five white women in the room and only three women of color, and that she didn’t trust white women. Especially white women from the South. At that point, I kind of tuned out because I was so used to hearing this type of talk from Tamika. But then I noticed the energy in the room changed. I suddenly realized that Tamika and Carmen were facing Vanessa, who was sitting on a couch, and berating her—but it wasn’t about her being white. It was about her being Jewish. ‘Your people this, your people that.’ I was raised in the South and the language that was used is language that I’m very used to hearing in rural South Carolina. Just instead of against black people, against Jewish people. They even said to her ‘your people hold all the wealth.’ You could hear a pin drop. It was awful.”

Reached by Tablet, Wruble declined to comment on the incident. Multiple other sources confirm that soon after, Wruble was no longer affiliated with the Women’s March Inc.—as the nascent group was starting to be known.

Over the weekend of Feb. 3, the Women’s March held a retreat in Rhinebeck, New York, at the Omega Institute. The National Committee, around 50 people, convened to spend the weekend decompressing data. At the retreat Mallory presented a last-minute plan for upcoming National Women’s Day: a strike, to be called Day Without a Woman. Harmon was shocked. “We’re going to ask women not to go to work?” she recalled saying, out loud, at the time. “I was like, ‘I’m sorry, you can’t do that to right-to-work states. We cannot tell a woman who makes $30,000 a year and a single mother that this is her duty. She could get fired for this!”

Others agreed, and also noted the impossibility of the timing: Planning a strike in 30 days seemed to speak directly to the leaders’ inexperience in organizing national activism. “They don’t have a clue what they’re doing,” Morganfield told Tablet. “They were chosen for optics—for the image they brought to the march. They believe that being in the right place at the right time for this march and this movement made them the founders—but it didn’t.”

During this weekend retreat, with lawyers from Skadden, Arps present the entire time, another thing happened—a change to the organization and its leadership.

The signatories to the original not-for-profit Women’s March Inc. were Bob Bland, Breanne Butler, and Evvie Harmon. At the retreat, “we went through what we had discussed and then we had our big kumbaya circle of love,” Harmon told Tablet. “After that broke up and everybody was boarding the buses, that’s when the Skadden lawyer came up to me with some papers saying, ‘You need to sign here to dissolve this entity that you and Bob created. And sign here to be a part of the entity that we just created.’ After I signed the first document, I went to sign the second one and the lawyer said, ‘Oh wait, you’re not Breanne Butler,’ and then she walked away. I looked at her and said, ‘What are you talking about? What just happened?’ She said quickly, ‘Oh, I’m gonna go find Breanne,’ and she basically ran away from me.”

Harmon claimed to Tablet that she believed the original organization was dissolved and a new one was created. In a statement to Tablet, the Women’s March denied any such claim—and described the event as nothing more than simple document updating. “On February 28, 2017 the Certificate of Incorporation of Women’s March, Inc. was amended and restated to effect certain changes consistent with the requirements of New York’s Not-for-Profit Corporation Law and the Internal Revenue Code. … The original corporation formed December 1, 2016 was never dissolved.”

But an email to the whole Women’s March network on March 3, 2017, does say that changes were made to the board—which now, indeed, no longer included Harmon:

A few weeks ago, the National Organizing Team had a retreat to discuss possibilities for the future of the Women’s March entity,” the email read. “As an outcome of the retreat, we set up an Interim Board of Directors in order to establish a 501(c)(4) organization. The organizational structure will help facilitate a decision-making process that will allow for things to be accomplished, to protect the assets that we have accumulated since November, and to help steer the conversation on what the Women’s March will be moving forward—taking into consideration feedback from the larger National and State teams.

The Interim Board includes the following people:

Bob Bland, Women’s March on Washington National Co-Chair

Breanne Butler, Women’s March on Washington Head of State & Global

Janaye Ingram, Women’s March on Washington Head of Logistics

Tamika Mallory, Women’s March on Washington National Co-Chair

Carmen Perez, Women’s March on Washington National Co-Chair

Linda Sarsour, Women’s March on Washington National Co-Chair

Indeed, based on documents provided by a source connected to the Women’s March and reviewed by Tablet, it appears that, beginning at this time, there were two new entities operative. One is Women’s March Inc., a 501(c)(4), which is a “tax-exempt as a social welfare organization,” according to the IRS, “and must not be organized for profit and must be operated exclusively to promote social welfare.” This is the Women’s March entity that donors have given millions of dollars to through fundraising sites like the GoFundMe-backed CrowdRise.

The Women’s March was obviously on its way to becoming a valuable brand, receiving millions of dollars in donations and raking in millions more worth of merchandise: T-shirts, pins, bags, mugs, and more. It began coordinating with a merchandising partner, The Outrage, which describes itself as a “female-founded activist apparel company.” (The Outrage also has a line with actress-turned-activist Rose McGowan, complete with #RoseArmy merch.) And in March of 2017, Women’s March Inc. filed a federal trademark registration for the Women’s March with the United States Patent and Trademark Office. It was met with much opposition. As Refinery29 reported, 14 separate organizations opposed the mark. “You do not trademark a movement,” Shook told us. “The Women’s March should belong to all of us. The sister marches don’t get a dime. They’ve been asked to be transparent over and over.”

***

Over the year that followed, the Women’s March continued to grow, publishing its book, raising money, and putting on new events. In October 2017, the group held a Women’s Convention. Attendance was reported to be high for the whole event, and was packed for the summit’s most popular panel, “Confronting White Womanhood.”

On March 11, 2018, the Women’s March had their biweekly phone call with national organizers. The public controversy had started to explode over Mallory’s attendance at the Saviours’ Day event, during which, in the course of a three-hour speech, Farrakhan blamed Jews for “degenerate behavior in Hollywood, turning men into women and women into men.” Angie Beem, president of the Washington state chapter, remembered that phone call.

“Many of us were upset,” Beem told Tablet. “She is the face of a women’s march, and our mission and values are equality and inclusion. To openly praise someone like this went against everything we were supposed to stand by.” Beem described a sense of awkwardness as Mallory went on to defend Farrakhan to over 40 women on the call. And she wasn’t alone, Beem said; Perez and Bland jumped in to defend him as well. “They said to us: ‘You know, he has done some great things for people of color.’ They didn’t denounce anything he said, they only did that recently. Some state people supported them and some who were very brave stood up to them. One woman said something like, ‘Just because somebody does one good thing doesn’t mean they are excused for everything else.’ They said, ‘We hear you.’ But then they refused to do anything about it.”

A few weeks later, in an email dated March 29 between Beem and Mrinalini Chakraborty, who at the time was the Women’s March national head of field operations & strategy, Beem wrote that the Washington state chapter was taking heat for the current controversy and that it would be best if at least two of the co-chairs were removed. “This particular issue has been hard for many of us and believe me, we are working internally to put in better systems in place so that this doesn’t happen in the future,” Chakraborty replied, according to an email seen by Tablet. “People have been hurt and we need to heal before we can move forward. However, I do think that it’s important we don’t talk about ‘removing people from leadership.’” Chakraborty did not respond to a request for comment.

It was around this time that Morganfield says she first heard that Nation of Islam members were acting as security detail and drivers for the co-chairs. “Bob called me secretly and said, ‘Mercy, they have been in bed with the Nation of Islam since day one: They do all of our security,’” Morganfield told Tablet.

Two other sources, with direct knowledge of the time, also claimed that security and the drivers for the co-chairs were members of the Nation of Islam. And this was certainly the case in the women’s previous organization. A May 2015 photograph on Sarsour’s Facebook page shows a group of men wearing suits and bow ties in the signature Nation of Islam style. Her caption above the photo reads: “FOI Brothers, security for the movement,” using the acronym for Fruit of Islam.

Disgusted not only with the co-chairs’ connection to Farrakhan but the way they were all handling what she saw as the legitimate public outrage over it, Morganfield, too, asked privately for their resignations.

“I talked to everyone, and I said it to every last one of them: Tamika [Mallory] needs to resign—not just because of her Farrakhan connection, but because of how she handled it afterwards. I said Linda [Sarsour] also needs to step down. Her controversy and the things she keeps saying and doing are detrimental to the movement.” When Tablet asked Morganfield whether she believes the co-chairs are anti-Semitic, she offered a terse answer: “There are no Jewish women on the board. They refused to put any on. Most of the Jewish people resigned and left. They refused to even put anti-Semitism in the unity principles.”

In an interview with Tablet, Bland categorically denied ever making this call to Morganfield, and both she and Mallory denied knowing of any connection between their security firm and the Nation of Islam. “Women’s March has no relationship with or financial ties to the Nation of Islam,” the group stated in their follow-up email to Tablet. The statement went on to say, “We denounce anti-semitism, and there should be no confusion about that.” It ends on a note of regret. “We attack the forces of evil, not the people doing evil. We understand our failure to clearly articulate this difference early—fighting anti-semitism vs. denouncing Farrakhan—has caused pain, and for that we are deeply sorry. We thank our critics for highlighting this lack of clarity so that we can do the work to undo the harm caused.”

It’s a noble sentiment but hard to square with the evidence. Responding to a query last month from Tablet contributor John-Paul Pagano, the group sent an emailed reply that read, in part: “Women’s March has no financial ties or relationship with the Nation of Islam. … Our senior leadership has been subject to extreme threats of violence. For their safety, we engaged licensed security firms as needed for credible threats. For legal and moral reasons, we do not ask for the religious affiliations of vendors, consultants, or employees at any level.”

Statements by Sarsour tell a different story. In a Facebook post from Sept. 30, 2017, Sarsour writes about an incident in which she was harassed in New York’s Penn Station. “What breaks my heart to pieces is that I don’t even feel safe in my own city,” she laments before offering a word of gratitude to her security detail: “thank you to the brothers who keep me safe so I can continue to do what I do.”

“She needs to be surrounded by FOI!” a Facebook user wrote in the comments under the post.

“I usually am brother,” Sarsour replied.

In their initial phone interview with Tablet, Mallory and Bland at first declined to name the security agency they employed, citing security concerns, but finally agreed to confidentially provide the firm’s name so that it could be verified—with Tablet guaranteeing in writing that it would not be published or made public in any way. However, several days later in their follow-up email, they wrote, “We have already shared receipts with a media outlet and do not want to have the name of our security firm out with multiple outlets.” It’s an apparent reference to an article in The Intercept, which offered this winding account of the Women’s March security practices: “the group provided invoices from a reputable security consulting firm for its October 2017 convention. The involvement of the international firm does not rule out the possibility—indeed, the likelihood—that the private security firm’s operation in Detroit, where the convention was held, employs some guards who are practicing members of NOI, but it rebuts the charge that the Women’s March directly contracted with the Fruit of Islam, the Nation’s security wing.”

In any case, Morganfield and others began pointing to what they said were deeper problems. “There is no LGBTQIA representation on their Board of Directors—this is not an intersectional organization—it’s smoke and mirrors,” said Morganfield. “Their Disability Caucus has one person in it. One. Their Veterans Caucus HAD one person in it. They no longer have a Veterans Caucus.”

In August of this year, the Black Women’s Blueprint, a Brooklyn-based organization, penned an open letter to the Women’s March echoing some of the same sentiments: “As women of African descent and Black feminists, many of us have watched the Women’s March these past eighteen months as the movement squandered its popularity, its platform and the support of all representations of women and girls including our own public letter encouraging Black women to march on January 21, 2017,” the statement reads. “We urge you beyond the elections, ground your work in coalition building and healing justice, and be present for the women across identities who still see no place in the Women’s March. We urge you to embody the intersectional feminism which continues to give Black women, LGBTQ+ and gender-fluid people at the margins the language to name our oppression.”

***

On Nov. 19 of this year, Teresa Shook publicly called for the current leaders to step down—opening the floodgates for numerous critics inside of the movement to openly express their reservations with the co-chairs. This time, most of the critics were from within the movement—and they weren’t interested in shopworn ideological issues. They were, instead, much more focused on finally bringing to light what they claimed were managerial and fiscal questions—leading the group’s finances, long a mystery since they had delayed filing mandatory tax forms, to begin seeping out into view.

That same month, a group of journalists from The Daily Beast showed up at the Women’s March offices in New York. For months, they had been sending written requests to see the group’s 990 tax form, which, as a nonprofit, the group is legally required to provide to the public—and the reporters finally decided to do so in person. A representative for the group claiming that their printer was broken promised to turn them over in 24 hours and did so—but not, it turned out, before sending them first to another publication, The Intercept, which, within hours, published an article that offered a generally favorable take on what the documents revealed. “Questions about the Women’s March’s finances follow a long line of attacks against the group’s leadership, mostly from figures on the right,” the piece said, before going on to describe the papers’ contents as standard—even bland.

But the analysis eventually offered by The Daily Beast revealed a more complicated picture. It showed, for instance, that revenue at The Gathering for Justice, the organization that acted as the Women’s March’s fiscal sponsor, increased by more than six times between 2016 and 2017, from $167,021 to more than $1.8 million. It was not immediately clear how much of the increase involved Women’s March-specific funds. Other details too were omitted from The Intercept article which, perhaps due to being rushed out, never mentioned The Gathering for Justice. It’s a particularly notable omission given that the Women’s March annual report itself notes: “The majority of the 2017 Women’s March on Washington was paid for by our fiscal sponsor, The Gathering for Justice.”

***

The Gathering for Justice was founded in 2005 by actor and left-wing political activist Harry Belafonte with the mission to “build a movement to end child incarceration while working to eliminate the racial inequities in the criminal justice system that enliven mass incarceration.” Around the time this new nonprofit was getting started in New York, Carmen Perez was involved in issues related to incarceration in her native California, working as a probation officer and for a nonprofit called Barrios Unidos. Her boss at Barrios Unidos, an early mentor named Nane Alejandrez, served on the Gathering for Justice advisory board and introduced Perez to Belafonte. In 2008 she joined the Gathering as a national organizer and in 2010 relocated to New York to become the group’s executive director. In 2013, Perez and another activist named Marvin Bing Jr, who now works for Amnesty International, launched a new initiative under The Gathering for Justice auspices called Justice League NYC.

With the League officially described as an “initiative” under the Gathering, the two justice organizations are really one body. The Gathering for Justice and the Justice League share both a physical address and a website. Where they differ is in their tactical approach and target audience. Justice League functioned as the “rapid response arm of The Gathering,” Perez explained in a 2016 interview. “The work we do at Justice League NYC is more visible where the work within The Gathering is long-term.” The group’s first event, a conference held in September 2014, showcased what would become the leadership roster of the Women’s March: Carmen Perez, Tamika Mallory, Linda Sarsour, and Michael Skolnik were all in attendance. Only Bob Bland, not yet known to any of them, was missing.

The Gathering for Justice did not respond to requests for comment.

Mallory was born in the Bronx to activist parents, Stanley and Voncile Mallory, who she described to the Amsterdam News as founding members of Al Sharpton’s National Action Network (NAN). Their daughter started working at NAN at the age of 15 and cut her political organizing teeth at the organization, climbing the ranks until, at 28, she was named executive director—the youngest in its history.

“Linda Sarsour Is a Brooklyn Homegirl in a Hijab,” announced the memorable headline of a 2015 New York Times profile that established Sarsour as a figure in national politics. The oldest of seven children born to Palestinian immigrant parents in Brooklyn’s Sunset Park, Sarsour’s political career began shortly before 2001 at the Arab American Association, where she would work for more than a decade. Her profile in New York politics rose in the post-2001 era as an advocate for the city’s Muslim community. Through that process, the Times recounted, her “fight against police incursions in her own community awakened her to similar problems in others.” Eventually, Sarsour’s political advocacy put her in the same orbit as the members of the Justice League. “It’s like Linda says,” Mallory was quoted in the Times story, “‘I’m gonna help y’all get your people straight and I expect you to come help me get mine straight.’”

Skolnik grew up in an upper middle class Jewish household in New York’s Westchester county to parents he has called “aging hippies.” Through family connections, he got an early opportunity interning for the documentary filmmaker Michael Moore. After college, he teamed up with director Lori Silverbush, another family connection, to make the feature film On the Outs, about three young women dealing with poverty, crime, drugs and prison in Jersey City. A run of documentary films followed until in 2008, inspired by the election of Barack Obama as president, he had a change of heart. In 2014, Skolnik described his decision to leave the film industry: “What to do after such a victorious election night? Well … I woke up the next day and decided to retire. I was only 30 years old and retirement sounded much cooler than a career change. If Jordan could leave basketball, I could leave the movie business.”

As it turned out, he had a landing pad already set up: While making one of his documentaries, Skolnik had met hip-hop legend and impresario of the Def Jam label, Russell Simmons. In 2009, Simmons appointed Skolnik as his own political director and hired him to run a celebrity pop culture and news content site he owned called GlobalGrind.

From the beginning, Justice League had one foot in the world of professional political protest and the other planted in the halls of power. Skolnik had connections of his own and through Simmons to powerful political figures like New York’s Gov. Andrew Cuomo as well as to celebrities like Jay-Z and Beyoncé. At the inauguration of New York’s Mayor Bill de Blasio in January 2014, Belafonte gave the keynote address.

There were other forces, too, backing the Justice League—though it wasn’t always clear by what means. The international NGO Amnesty International was an early supporter, participating in a 2015 fundraising event and donating $20,000 to the Gathering for Justice in 2017 as documented on their tax returns. The powerful local branch of the Service Employees International Union (1199SEIU),was another influential backer. According to the official Gathering for Justice mini history, in 2010, Perez formed “a meaningful partnership with 1199SEIU by helping build their young workers program, called Purple Gold.” In addition to her work heading the Gathering for Justice and Women’s March, Perez has been a salaried employee of 1199SEIU since 2010.

In the summer of 2014, the unrest that had begun simmering after the fatal shooting of Trayvon Martin erupted into a grassroots movement agitating for change on the very issues Justice League was created to address. Despite New York’s historic role as a hub of political activism, the marches and demonstrations in the city were fairly muted through the summer and fall of 2014, even as they were roiling other parts of the country. Then, on Dec. 3, 2014, a grand jury returned its decision on the death of Eric Garner, an unarmed black man suspected of illegally selling cigarettes. A New York police officer used a chokehold on Garner that was prohibited by department regulations, killing him. The incident was filmed, but the grand jury declined to indict the officer.

After months of relative quiet, a large protest movement seemed to develop overnight in New York. From the beginning, Justice League was visible at the public protests throughout the city. Along with other activist groups adept at organizing over social media, Justice League turned its Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram into shareable billboards. A tweet or a Facebook post broadcast information that told people where to turn up and provided the phrases and messaging points that would in turn become, first, chants at the marches, and then the next day’s headlines. In contrast to Occupy, Justice League had a cadre of young people of color who gave it a visible presence at the protests, wearing shirts with the group’s logo and often using bullhorns and established organizing tactics, leading the call-and-response chants. In a large crowd looking to express itself coherently, a small determined group with basic organizational competence can direct forces far larger than itself and Justice League proved adept at assuming that role.

In the aftermath of the Garner trial, as large-scale protests began building in New York, Justice League pulled its other advantage—celebrity connections—into the mix. On Dec. 8, 2014, black T-shirts with the phrase “I Can’t Breathe”—Eric Garner’s haunting final words before death—printed in stark white letters across the chest were handed to players for the Brooklyn Nets basketball team. The shirts were then worn onto the courts at Brooklyn’s Barclays Center in front of a crowd that included royalty, cultural and otherwise: Beyoncé and Jay-Z were in attendance, as were Prince William and Kate Middleton—as well as a national television audience. “We were able to deliver shirts to the Brooklyn Nets, and they wore our shirts in solidarity with the work that we’re doing out here,” Carmen Perez said at the time. An item in the next day’s New York Times added a detail about how the shirts got into the player’s hands: “Skolnik, meanwhile, knew he needed to get Jay-Z on board.” Somehow, he did.

While the Justice League was using its celebrity connections to create a viral media spectacle on the court, organizers wearing its logo emblazoned in white print on black shirts were simultaneously leading protests in the streets right outside the arena.

Eric Garner Jr., @UncleRUSH and our team member @Awkward_Duck #royalshutdown pic.twitter.com/z17igFyELi

— Justice League NYC (@NYjusticeleague) December 9, 2014

Then, in October 2015, a large rally was held in Washington, D.C., organized by Louis Farrakhan to commemorate the 20th anniversary of the Million Man March. Three representatives from the Justice League were present: Perez, Mallory, and Sarsour. “Let’s keep it real,” Perez told a reporter who interviewed her at the rally. “The Minister reached out to us and he was extremely intentional about who needed to show up today, so here we are.”

They weren’t the only ones with direct connections to the leader of the Nation of Islam. Russell Simmons calls Farrakhan—who often and in various forms argues that “Satanic Jews have infected the whole world with poison and deceit”—his “second father.”

Ironically, the hip-hop mogul also simultaneously ran a flashy outfit called the Foundation for Ethnic Understanding, with the controversial, five-times-married New York City Rabbi Marc Schneier. Though he ended his employment with his former boss in 2015—before Simmons’ departure from public life in 2017 amidst multiple sexual assault allegations—and recently told Tablet that he and Simmons have no current relationship, Skolnik seems to have learned a lot from the onetime king of Def Jam about the art of high-profile activism. He had certainly become influential, though to some his success also seemed representative of an emerging activist culture on the left that too often valued style and virality above substance.

“For me, successful agitprop is not fucking preaching to the converted, which is what sickens me,” Anthony Bourdain said, in his final interview before his death. “Do you follow Michael Skolnik? I can’t bear to read … I can’t fucking bear it. I almost want to like, become a Republican reading this. This is how deeply offended I am by self-congratulation, his saccharine, hashtag-driven expressions of solidarity, his messianic certainty that he is in some way a vanguard of something. It really makes me wanna vomit.”

***

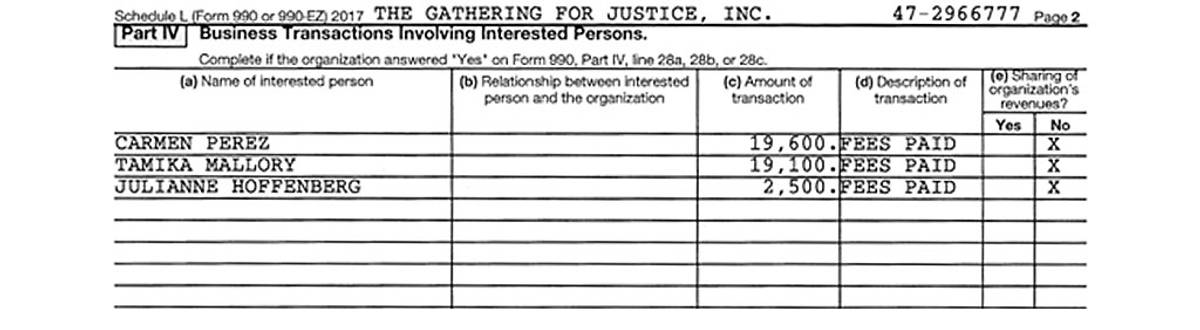

It’s not even possible—given their fiscal relationship—to evaluate the Justice League and the Women’s March separately. “The records suggest that the Women’s March leaders receive compensation at the low end of major nonprofit executive pay,” according to the Intercept article, which cites Mallory making $70,570 in salary. But this omits the money the co-chairs have received from the Gathering for Justice. Mallory was paid $19,100 under the “business transactions involving interested persons” section of the Gathering’s 990 tax form while Perez earns more than twice as the Gathering’s executive director as she does from the Women’s March. The additional sums that we’re talking about here for the co-chairs are not exorbitant—an extra $20,000 does not make Mallory a member of the 1 percent, but what they do suggest is that to get a full picture of the Women’s March finances requires a combination of effort and knowing where to look.

Perhaps the single biggest question that arises from reviewing the Women’s March financial disclosures is how to account for all the money raised through organizations’ various revenue streams. The “total revenue” reported on the Women’s March 990 form from 2017 is $2,533,074. Yet, just through donations on the website CrowdRise, an “online social fundraising platform” owned by GoFundMe, the Women’s March—or various entities directly connected to the national Women’s March—appear to have raised more than $3 million. Donations for the initial January 2017 March on Washington have already reached $2,069,883, and, despite the event being almost two years old at this point, are still trickling in. Three days prior to the publication of this article, an individual contributed $50 in the name of “standing for justice.” Counting the March on Washington, the Women’s March appears to have eight separate fundraising efforts on CrowdRise for causes including events to “Cancel Kavanaugh” and “End Family Detention” that have raised a total of $3,131,071. Just the money from CrowdRise is over half a million more than the Women’s March has reported so far in total revenue to the IRS.

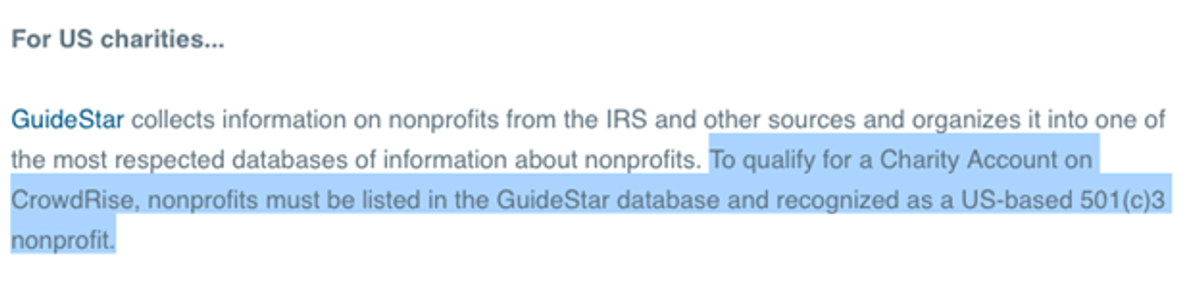

It would appear that the Women’s March has been a banner success for CrowdRise—a high profile and much lauded progressive cause raising millions on its platform. And yet, it’s not at all clear that the Women’s March is even eligible to raise money on CrowdRise. “To qualify for a Charity Account on CrowdRise, nonprofits must be listed in the GuideStar database and recognized as a U.S.-based 501(c)3 nonprofit,” the site states and details in its terms of service. But the Women’s March is not a 501(c)3 nonprofit, it’s a different kind of organization, a 501(c)4, and it was not listed on the Guidestar database as the requirement clearly states. Reached for comment about this apparent discrepancy, CrowdRise replied with a one line answer: “We did look into it. Women’s March Inc. is a 501(c)(4). Thanks!”

Other notable items on the financial disclosure forms include the $167,299 that the Gathering for Justice earmarked for “sponsorship” and the fact that over $500,000 in public support for the group, a little under one quarter, appears to come from donors of roughly $44,000 or more.*

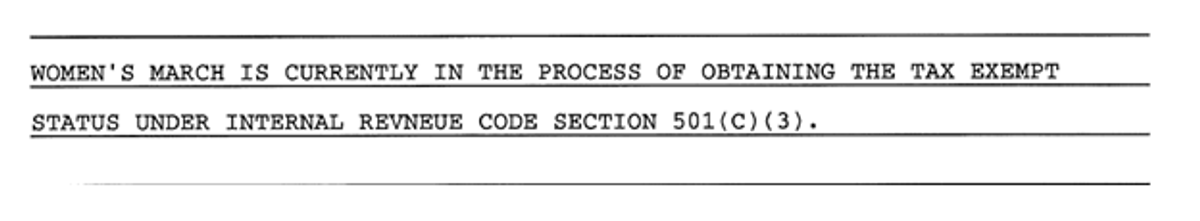

To make matters murkier, the Gathering for Justice indicates on both its 2016 and 2017 tax forms that the “Women’s March is currently in the process of obtaining the tax exempt status under internal revenue code section 501(c)(3). Yet when Tablet asked the Women’s March co-chairs about the status of their application, Bob Bland responded: “to clarify we are a 501(c)(4) social and political advocacy organization.”

After more than a year of local chapters of the Women’s March asking national to provide information on its finances, the group finally released, along with its tax documents, a 10-page glossy annual report for 2017. The document ended up raising more questions. For instance it shows the organization paying $255,747 to “consultants and contractors” for the year 2017 but does not name the individual contractors or show how much each received.

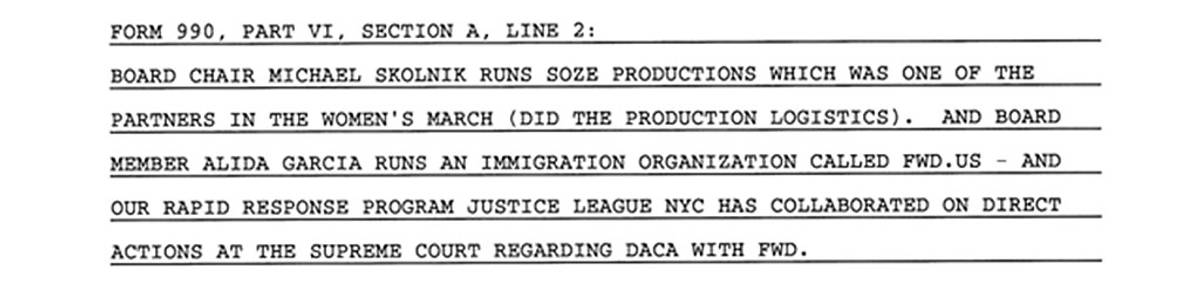

On the Gathering’s 2016 tax form, Michael Skolnik’s consultancy company Soze is listed as “one of the partners in the Women’s March.”

“The Soze Agency provided support on some of the production logistics for the actual march,” Solnik told Tablet, but did the work “pro-bono and received zero compensation.”

Currently, Skolnik says that Soze is not contracted to provide any services to the Women’s March and describes his own relationship to the organization as “none.”

Moreover, on March 1, 2018, NEO Philanthropy, a not-for-profit group that serves as a fiscal sponsor for left-leaning causes, quietly announced they had taken on a new project, the Women’s March Network. A couple of months later in June the URL womensmarch.org was transferred from Bland to NEO Philanthropy. A website was built and launched with no announcements to the public or Women’s March members about NEO Philanthropy or womensmarch.org. In fact most members we spoke to didn’t even know the website existed and had never heard of NEO Philanthropy. Tablet received documents showing that Women’s March Inc. is operating as a 501(c)(4) and Women’s March Foundation Inc. is operating as a 501(c)(3). It is unknown what entity Women’s March Network is doing business under. What’s clear is that there are multiple entities with money flowing in different directions for the Women’s March and little transparency. While it is perfectly legal to have affiliated 501(c)(3) and 501(c)(4) organizations, both need to be governed by separate boards of directors, maintain separate bank accounts, have different names and different letterheads to avoid violating tax laws.

Indeed, critics were not mollified by what the group had released. Morganfield, one of the most vocal, detailed her reaction on her own Facebook page: “I develop training programs and public forums for a living so I know everything that goes into it. I am also familiar with the costs involved and I feel fairly confident in asserting the costs on these financials for various ‘programs’ are wildly inflated,” she wrote. “While their individual salaries appear to be low—it represents ‘direct compensation.’ Indirect compensation would be monies paid to their individual ‘consulting companies’—did they receive indirect compensation as well?” [UPDATE, Dec. 12, 3:30 p.m.: After publication, the Women’s March provided this statement: “No consulting companies connected with individuals associated with the work on the March on Washington received compensation and we have documents and vendor receipts from the 2017 convention to prove it as well.”]

Morganfield went on, citing her own direct experience with the group:

For those of us on the inside 2.5 million as large as that number is—appears to be deceptively low. I witnessed us putting out a call for donations at 8am and amassing 50K in donations by 5pm. Where is the rest of the money? What I know for sure from this financial report as flawed as it is—this group took in 2.5 million dollars and didn’t give a cent to the states, didn’t give a cent to enhance the work being done inside gun control advocacy, reproductive health rights, grooming young women for political leadership, Black Lives Matter, initiatives by WOC, initiatives to counter antisemitism, helping the embattled immigrants, or even helping the Muslim community that has been so attacked by this administration. They took in all that money and kept all that money for themselves—oh yeah and their specious programming initiatives. And that is what I find most problematic. If you pull out WOC and use them as your smokescreen to allow you to spew antisemitic rhetoric couldn’t you at the very least toss them a few dollars?

“They get millions of dollars, and who does all the work? The states,” said Morganfield, in an interview. “D.C. was their biggest chapter. We never received one dollar from them,” she told Tablet. “They promised us money. Never gave us a red cent. I’ve asked to see their financials at least 15 times. They won’t even answer emails.”

Faced with the questions raised by Morganfield and others, the Women’s March co-chairs told Tablet that it was never their intent to fund local chapters. “It’s not industry standard for nonprofits that have membership-based or chapter-based organizing to directly support their chapters on a money basis,” said Bland. “We are a very distributed network.” Mallory added: “It’s also important to note that many of the chapters have expressed—and we support the idea—that they want to be separate but working in community with us.” Mallory summed up their approach: “Folks have to be empowered to raise funds on their own and to really be a grassroots network as well, just the way that we are trying to model as a national organization.”

Confronted directly with Morganfield’s criticism of her leadership, Mallory was emphatic:

Let’s just say she did call for one of us to resign. What does that mean in the larger scope of the fact that 5 million people marched and many chapters across the country we’re operating? If you want to focus on Mercy Morganfield as one individual—as if she was the person who sacrificed every day over several months and put blood, sweat, and tears into this movement in order to make it what it is—that that makes me very uncomfortable, because we were the ones doing the work every single day. Mercy Morganfield is no different than any other detractor who may have something to say.

For many, the reaction from the co-chairs was depressingly predictable. In a conference call with the state chapter organizers on Nov. 29, Sarsour punted the swirling controversies as nothing but a little scuttlebutt. “It just happens often with women, unfortunate gossip and rumors and it’s very hurtful to us as our families are watching these conversation online.”

***

Sarsour also offered an explanation—perhaps more necessary after 11 Jews were murdered in a synagogue in Pittsburgh in October—for why Jewish women were left out of the organization’s unity principles. “It’s not because there was some deliberate omission,” she said. “The unity principles were written as a visceral response to the groups that were directly targeted by Trump during his campaign. … They were really written for the people who during campaign seemed to be the first on the list for this Administration. There was no deliberate omission of our Jewish sisters. In fact, you know, one of the groups that is one of the most directly impacted since in America are Sikh Americans, those are people who wear turbans and unfortunately, they are the largest group that are impacted by violent Islamophobic attacks. Even though they’re not Muslim, people think they’re Muslim.”

According to the FBI, in fact Jews are the most targeted religious group in America. 2017 had the most hate crimes based on religion of any year since 2011, up 23 percent over 2016—and the majority of those incidents, 58 percent, were against Jews, an increase of more than a third over the previous year.

Since it was conceived on the rooftop in the chaotic days after Trump’s election, the Women’s March has never really escaped the contradictions and internal conflicts present at its founding. There wasn’t any one rift that could be healed or moved beyond; there were many—over personalities, ideology, money and organization. Is it a 501(c)(4) organization called Women’s March Inc. or a different entity, a 501(c)(3) called the Women’s March Foundation? And why is it that there are two entities and the group will only acknowledge one? But those are not the only kinds of questions that have pulled at the seams of the movement. There are profound questions, too, about its core values and what, exactly people are marching for.

Over time, these questions became flashpoints. In one heated exchange, Julianne Hoffenberg, who works at the Gathering for Justice, lashed out at a woman on Facebook who criticized Sarsour for alleged anti-Semitism. “Did you march? You marched for Palestine,” Hoffenberg wrote. “You wore a pink pussy hat??? You advocated against the state of Israel and for Palestine.” The assertion that anyone who marched in January 2017 was marching against the state of Israel likely came as a surprise to most of the thousands of women present—including the hundreds who marched that day outside the U.S. Embassy in Tel Aviv.

“The statement attributed to Julianne Hoffenberg does not reflect her actual comment. Moreover, it was posted from her personal Facebook account,” the Women’s March wrote in an email to Tablet. Moreover, the group wrote, Hoffenberg, “holds no position in the Women’s March organization and is not a spokesperson for Women’s March nor for The Gathering for Justice.”

While she is not a spokesperson, Hoffenberg is the Gathering for Justice’s director of operations and, according to the group’s 2016 tax returns, its highest-paid employee.

Angie Beem, a microbiologist and president of the board for the Women’s March Washington State told Tablet that after this Jan. 3 anniversary march, the Washington state chapter will be dissolving. “The vice president of our chapter is Jewish,” Beem said. “She gave them that first opportunity to apologize and admit and say ‘we screwed up’ but they didn’t, so she was done.” After this year’s march, Beem said, “we are dissolving the organization.”

When Morganfield tries to sum up how and why it all went wrong, she sees the downfall of the Women’s March in a hunger for fleeting recognition and publicity that eclipsed the movement’s real political power. “The reason I joined the Women’s March is because I believe women could truly be the most powerful voting bloc this country has ever seen,” Morganfield said. “The problem with the Women’s March is that in order to stay in the news, they had to be like ambulance chasers: They chased every issue that could get them media coverage. That’s not strategy; that’s tactics.” Nor is she holding out hope that critical media attention will prove any more beneficial to the co-chairs than the adulation they received early on. “The response that gives them the most sympathy is ‘This is white women trying to come out against women of color,’” said Morganfield. “The context is always, ‘the white media are trying to bring down women of color.’ And in this case, they’ll probably say it’s white Jewish women, which of course discounts the fact that there are black Jews. There’s somewhere close to 300,000 black Jews! What about them? It’s just divisiveness.’”

For her part, Wruble agrees—and has pivoted her energy to a new organization devoted to women’s activism, called March On. “At March On, we approach things from a bottom-up rather than a top-down way. We take the lead from local organizers, and we understand that there’s no one-size-fits-all when it comes to organizing. Our organizers come from all walks of life and backgrounds. We’re diverse and intersectional in ways that people often don’t think about. Many women in red states, for example, couldn’t follow an organizing playbook crafted out of D.C. or New York City. The red states couldn’t participate, for example, in a general ‘women’s strike’—people would lose their jobs.”

Others have moved on in their own way. When Glamour named the new Women of the Year last month, the cover featured March for Our Lives activists, young women who survived the Parkland High School shooting in Florida. “The March for Our Lives founders are aware that their prominence and impact stems, in large part, from their being white and well-off,” read another profile in Wired. “They’ve responded by seeking out a wide range of allies. They speak frequently with Michael Skolnik, who runs a social impact consultancy called the Soze Agency …”

Morganfield doesn’t want to see disillusionment turn into cynicism. She’s hoping that those who felt inspired will continue to do so—and find ways to effect real and lasting female-driven change in American society. “This needs to be a blip in our radar,” she said. “We don’t have to call it the Women’s March. I think we still have an opportunity to pull this together. But it can’t be the Jewish women’s movement or Black womens’ or White womens’ or the Spanish women’s movement. We just need women voting together.”

Dec. 12, 3:30 p.m.: This article has been amended to reflect the following:

The Women’s March disputes that the Los Angeles and Georgia chapters are no longer part of the national network. Attempts to reach the LA and Georgia chapters of the Women’s March were unsuccessful at the time of this update. According to a report in Refinery29, the LA chapter is currently in a trademark dispute with Women’s March Inc.—and a related email from March 2018, seen by Tablet today, includes LA chapter head Emiliana Guereca strongly implying that there is no “working relationship.” The following chapters of the Women’s March were not included in the list of regional groups that had disaffiliated with the Women’s March: Florida, Portland, Barcelona, Canada, and Women’s March GLOBAL.

An earlier version misstated the sum of sponsorship money and misidentified its source. The correct sum is $167,299, not $169,000, and the source was the Gathering for Justice, not the Women’s March.

An earlier version incorrectly stated that “None of the other women in attendance would speak openly to Tablet about the meeting.” In fact, at press time, Tablet had contacted or spoken to six out of the seven people present at the meeting. That seventh person, Cassady Fendlay, reached today, offered a description of the events that aligns with the version described in the piece.

An earlier version of this story misstated the chronology of Vanessa Wruble’s departure from the Women’s March. Wruble remained a member of the Women’s March until late January 2017.

Leah McSweeney, co-host of the podcast Improper Etiquette, is a columnist at Penthouse magazine. Jacob Siegel is Tablet’s Scroll editor.