Holocaust Poetry, Saved Again

New translations of three astonishing poems, which evoke the horror of the Lodz ghetto and its aftermath

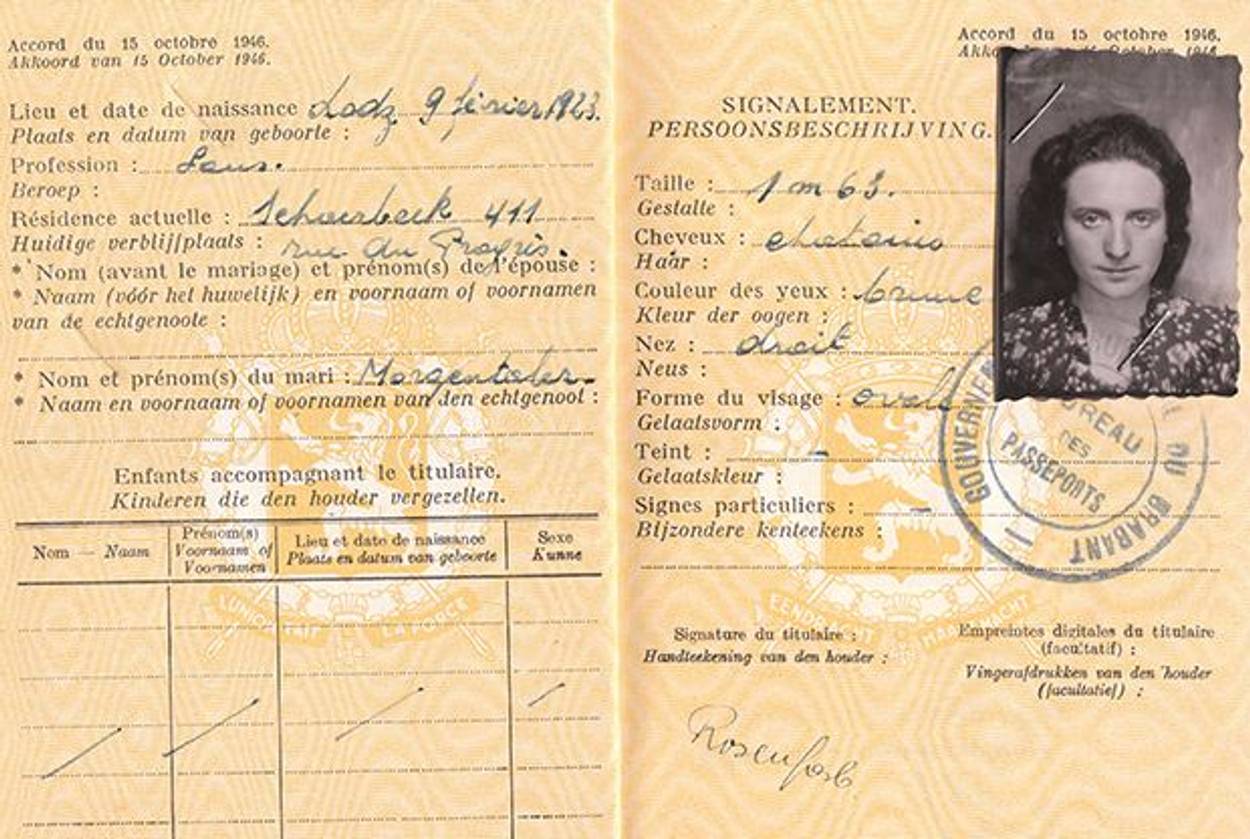

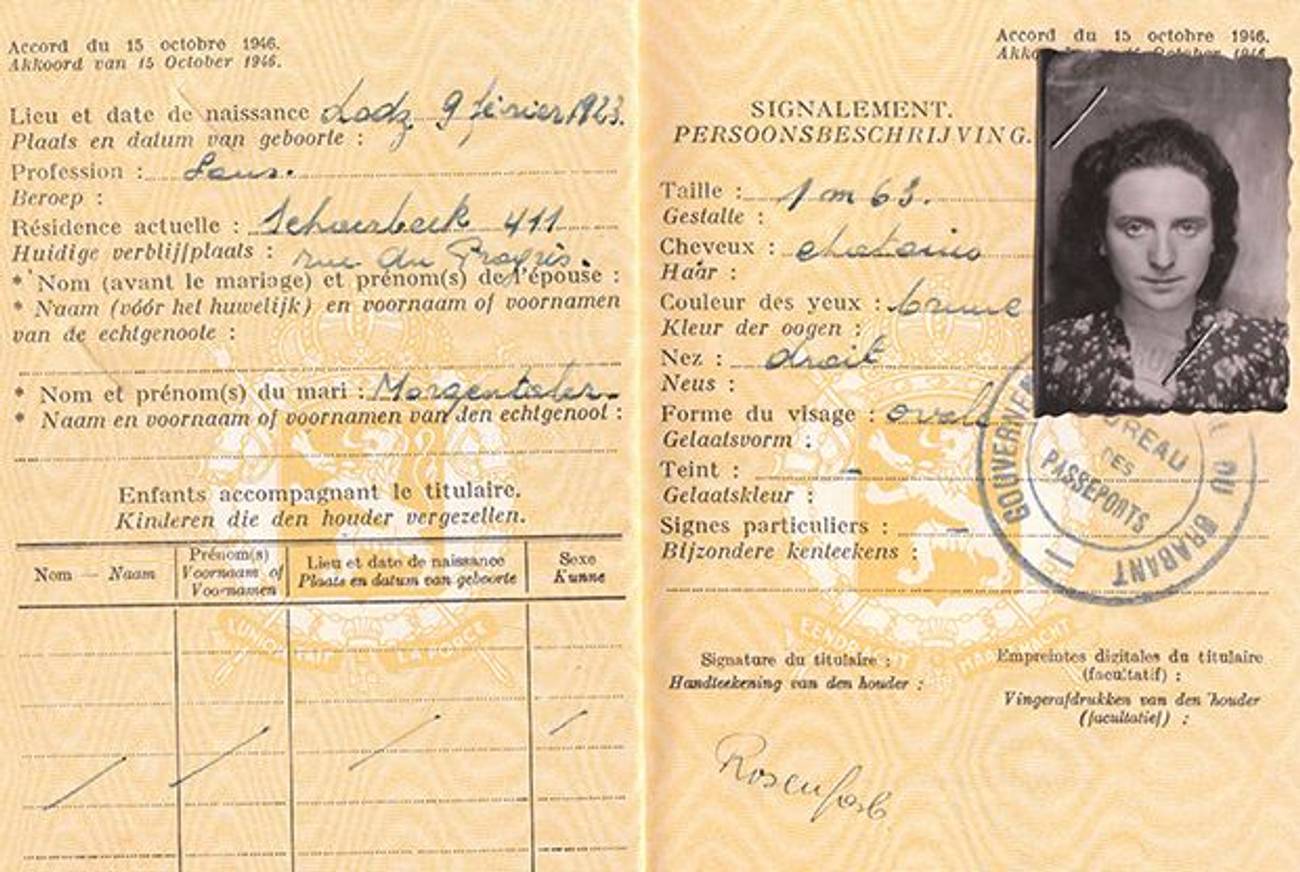

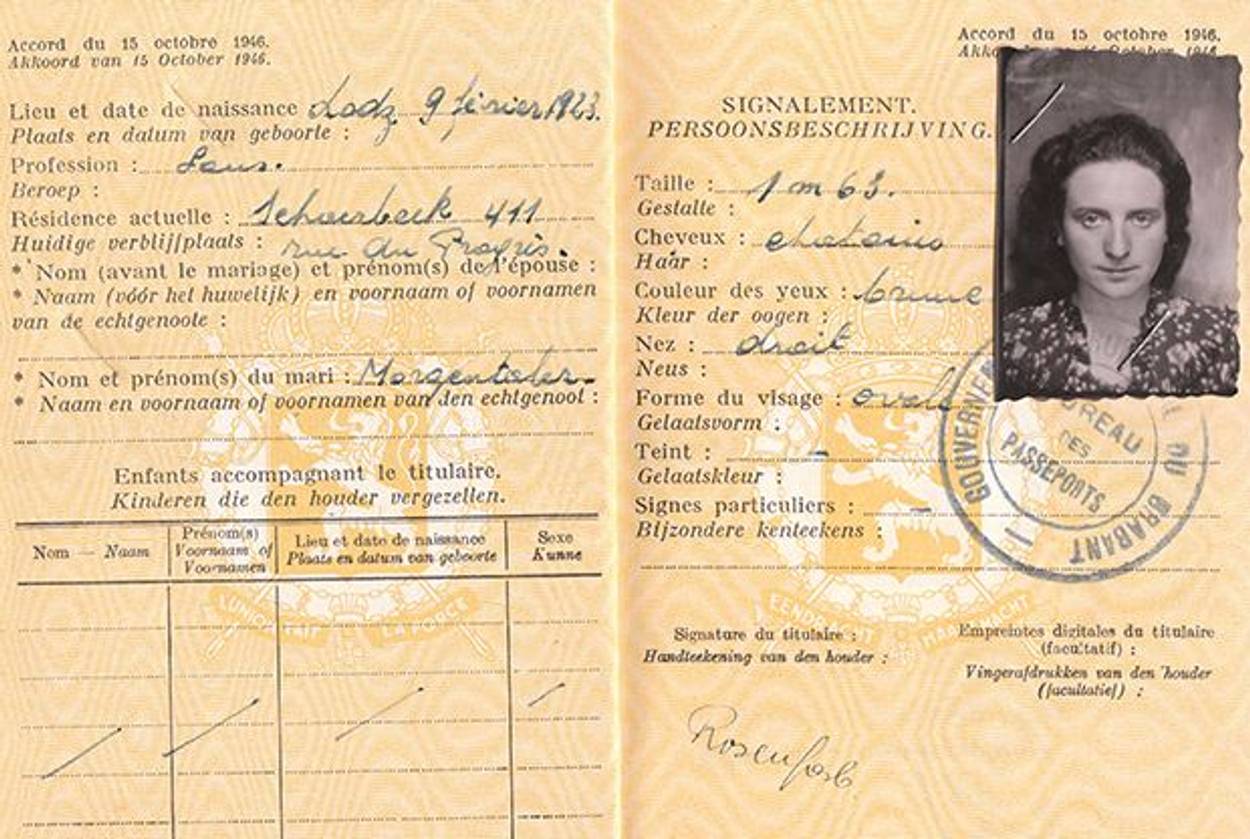

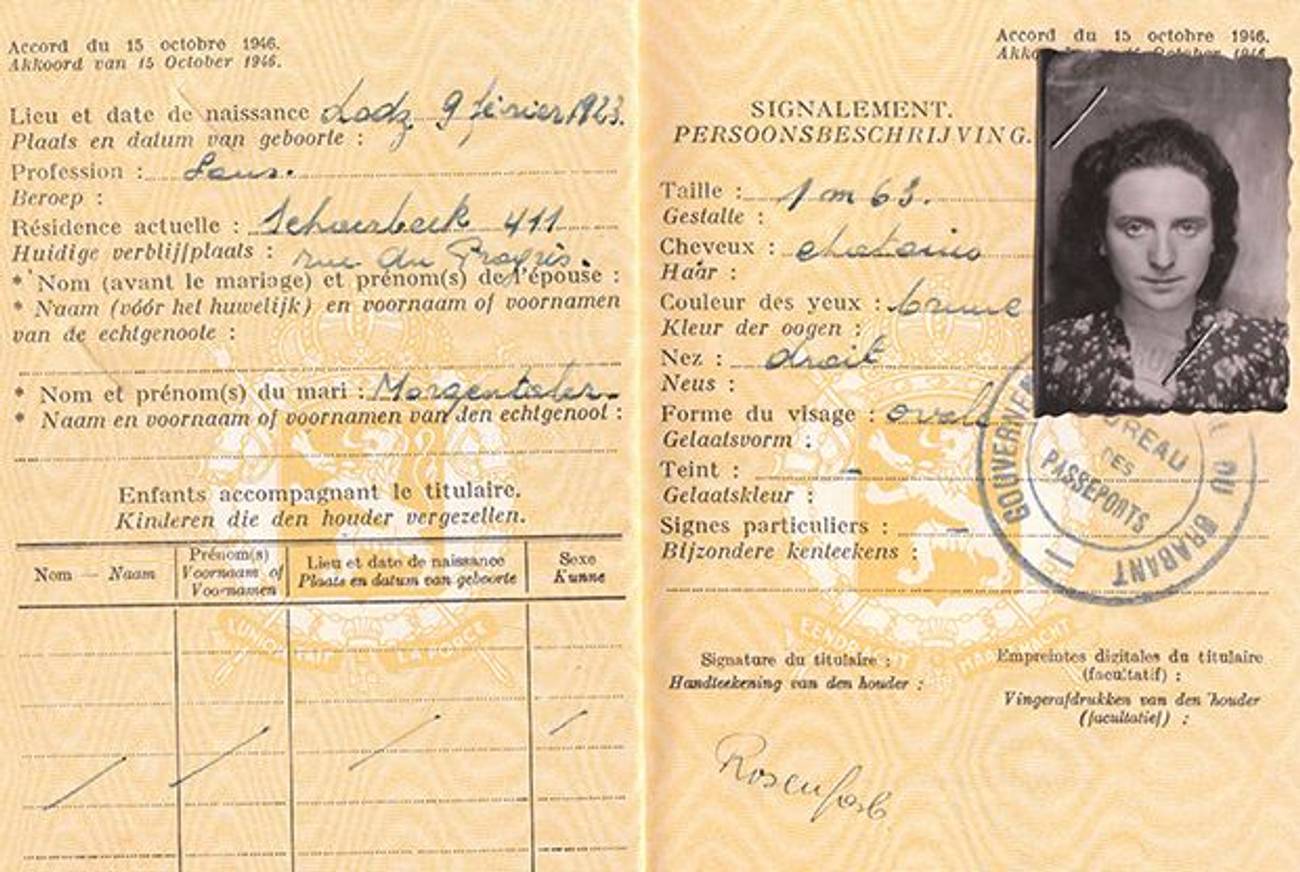

The following three poems are part of a collection of poems by the Yiddish writer Chava Rosenfarb that will be published in English in Spring 2013 by Guernica Editions of Toronto under the title Exile at Last: Selected Poems of Chava Rosenfarb. (Rosenfarb’s essay “The Last Poet of Lodz,” about her mentor, the Lodz ghetto poet Simkha-Bunim Shayevitch, appeared in Tablet magazine last year.) The introduction below was written by Goldie Morgentaler, Rosenfarb’s daughter; all of the following poems were translated from Yiddish to English by Rosenfarb.

***

Chava Rosenfarb was born in Lodz, Poland, in 1923. She was educated in Yiddish and in Polish. When she was 16, the war broke out. Along with her family and the rest of the Jews of Lodz, she was incarcerated in the Lodz ghetto from 1940 until the ghetto’s liquidation in August 1944, when she was deported to Auschwitz. After the war, she settled in Montreal, Canada, where she began a prolific literary career, which included the publication of three books of poetry, three multivolume novels, a play, and numerous short stories and essays, most of which were published in the Yiddish literary journal Di goldene keyt. All of her work was first published in Yiddish, but some of the novels and a short-story collection called Survivors are available in English. She is best known for her landmark Holocaust trilogy, The Tree of Life: A Trilogy of Life in the Lodz Ghetto, one of the seminal works of fiction about the Holocaust.

The first two poems below, “Praise” and “A Dress for My Child,” were published in Yiddish in Rosenfarb’s last collection of poetry Aroys fun gan eydn [Out of Paradise] (Tel Aviv: Peretz Farlag, 1965). “Praise” is a paean to ordinary life by a poet who had lived too much in extraordinary times. “A Dress for My Child” is similarly about the day-to-day joys and cares of motherhood. Both these poems were composed in Montreal, where Rosenfarb lived for most of her life and where she raised her two children.

The poem “Isaac’s Dream” was first written in the Lodz ghetto. It was lost when the knapsack containing all of Rosenfarb’s poems was ripped out of her hands at Auschwitz. She survived the selection and, along with her mother and sister, was sent to a slave labor camp near Hamburg, where she helped to build houses for the bombed-out residents of that city. There she managed to beg a pencil stub from a kindly German overseer and wrote what she could remember of her poems on the ceiling above her bunk. She then memorized the poems. After the war, she published them in her first book of poetry, Di balade fun nekhtikn vald: geto un andere lider [The ballad of yesterday’s forest: ghetto and other poems] (London: Oved, 1947).

Praise likewise the day

standing still as a water—

a mirror without a reflection.

Though hours that glide

through its hazy-pale surface

like breath-carried skaters

are shunning the lighted eye of awareness,

erasing their footprints

before they are falling—

Praise likewise that day

you will never remember.

Praise likewise that day

whose name is a riddle

and you are not sure,

is it now, is it later?

And all the accounts

with yourself and with others

are resting hidden

in white and gray sponges;

and words that you utter

and words that you ponder

resemble the minnows

that fall through ripped net-holes

deep into the silence …

Praise likewise that day

when you feel no discomfort

of soul or of body;

when moving your limbs

you don’t feel their burden

and you don’t hear the pulse

of time in your bosom;

and throughout your mind

reflections are swimming

like gossamer threads

without knots or connections—

not bound and not torn …

Praise likewise that day

when no letters are coming,

no tidings arriving,

not good ones, not bad ones—

when silent the bell at your door

and the telephone’s quiet;

and the loudest of echoes

that reaches your being

is that of a kiss

that your baby gives you

with lips sweet as honey …

When the light is down

and the end is approaching

and sudden at last

you find yourself standing

in a gate of deep darkness;

look once more behind you

to that bubble of being—

and praise it, that day

that drips out of existence,

dissolving unnoticed

in the night of oblivion.

I would sew a dress for you, my child,

out of tulle made of spring’s joyful green,

and gladly crown your head with a diadem

made of the sunniest smiles ever seen.

I would fit out your feet with a pair

of crystal-like, weightless, dance-ready shoes,

and let you step out of the house with bouquets,

bright with the promise of pinks and of blues.

But outside it is cold and dreary, my child,

the wanton winds lurking unbridled and wild.

They will mangle the dress of joy into shreds

and sweep the sun’s smiling crown off your head,

Shatter to dust the translucent glass of your shoes

and bury in mud the dreams of pinks and of blues.

From far away I can hear you call me and moan:

“Mother, mother, why did you leave me alone?”

So perhaps I should sew a robe for you, my child,

out of the cloak of my old-fashioned pain,

and alter my hat of experience for you

to shelter you from the ravaging rain?

On your feet I would put my own heavy boots,

the soles studded with spikes from my saviourless past

and guide your way through the door with a torchlight

of wisdom I’ve saved till this hour of dusk.

But outside it is cold and dreary, my child.

The wanton winds lurking unbridled and wild

will rip up the robe sewn with outdated thread,

bare your chest to all danger, to fear bare your head.

The heavy boots will sink in the swamp and will drown,

the light of wisdom mocked by the laugh of a clown.

From afar I hear you call me and moan:

“Mother, mother, why did you leave me alone?”

What a wretched seamstress your mother is—

Can’t sew a dress for her child!

All she does is prick her clumsy fingers,

cross-stitching her soul, while her eyes go blind.

The only thing that I can sew for you, my sweet, my golden child,

is a cotton shift of the love I store

in my heart. The only thing I can give to light your way

are my tears of blessing; I have nothing more.

So I must leave you outside, my child, and leave you there alone.

Perhaps dressed in clothing of love you will learn better how to go from home.

So I sit here and sew and sew, while in my heart I hope and pray—

my hands, unsteady, tremble; my mind, distracted, gone astray.

As I was standing, all set for my exile,

Doom staring at me from the road’s blinding end,

The door, like a book’s heavy cover, opened,

To bring forth a guest from the biblical land.

His body, half naked, a knife in his loincloth,

In sheep-leather sandals his tanned, bronze-like feet,

A bundle of firewood upon his shoulder—

He said, with a smile very boyish and sweet:

“Good morning, my girl; remember me, dearest?

You’ve waited for me so long—not in vain.

I’m Isaac, your bridegroom, ordained by the Heavens …

Through ages I’ve wandered to you, till I came.

Take off your dress. A sheet of plain linen

Is sufficient to drape round your navel and hips.

Undo your braids and let’s hurry, my sweetheart,

Your hand clasped in mine and a chant on our lips.

Thus will l lead you beyond the horizon,

Between north and south, through the west—to the east,

Until we will reach Mount Moriah, my dearest,

There to be married, to rejoice and to feast.

So come, let us hurry, the distance is calling.

Pray, why do you shiver with anguish and cry?

You’re asking why all that wood on my shoulder,

The glittering knife on my hip—you ask why.

Then turn your soul to my soul, my beloved.

Read your fate in my fate, while I explain:

Out of the wood I will construct an altar

And with love all redeeming set it aflame.

And the knife, my bride, I will file to its sharpest point

Up there, at the peak, on a rough mountain stone.

And who will be offered, you ask me?—then listen:

The offering, my dearest, shall be you, you alone.

A gift of life to the God of All Being,

As Abraham told me, his late-born son:

If you trust in love and love wholly trusting,

Then fear not, nor waver, dear girl, but come.

Though fire will blaze through the wood of the altar,

Flames licking your body, yet you shall see:

The knife will fall from my hand, and a miracle

Will happen to you, as it happened to me.

The rivers and seas shall sing Hallelujah!

The mountain pines, moved, will give praise to all life,

While the Voice Divine will, with thunder and lightning,

Proclaim me your husband, pronounce you my wife.

So hurry, my girl, the sky is already

Spreading its canopy, preparing the rite.

Come to the blue sacrificial fire—

Your last maiden stroll—to the altar, my bride.”

Thus he spoke. I smiled, then said in a whisper,

My eyes not on him, but fixed on the dark night,

Where another road was tracing its outlines

With the red of my blood, with signals of fright:

“Oh leave me, Isaac, you bronzed, sunny man.

This road is not yours, not mine is your day.

I head for those places you never have dreamed of,

Where altars do smolder with their unwilling prey.”

As I spoke a gale swept towards my threshold.

The tempest took hold of my hearth and my house,

Whistling through streets, through the yards of the ghetto,

Hissing with rage: “Juden raus! Juden raus!”

Thus I stepped forward with Abraham, my father,

Who wrapped his arm round me as if with a shawl,

While delicate Isaac, all tremble and flutter,

Pressed his tanned sun-kissed frame to the wall.

“You’re frightened, Isaac?” said I. “I’m your nightmare.

Awake and you’re back in your undying scroll,

Where Rebecca, your true betrothed awaits you,

To be taken with joy on her last maiden stroll.

Make haste, return to the Book that shall save thee.

Hide yourself in the Bible’s fairytale land.

For your God Himself walks with me and my father,

Right now, to the altar; with us—to His end.”

Chava Rosenfarb (1923-2011) is the author of the novels The Tree of Life: A Trilogy of Life in the Lodz Ghetto, Bociany, and Of Lodz and Love, and the short story collection Survivors. She was a frequent contributor to the Yiddish literary journal Di goldene keyt.