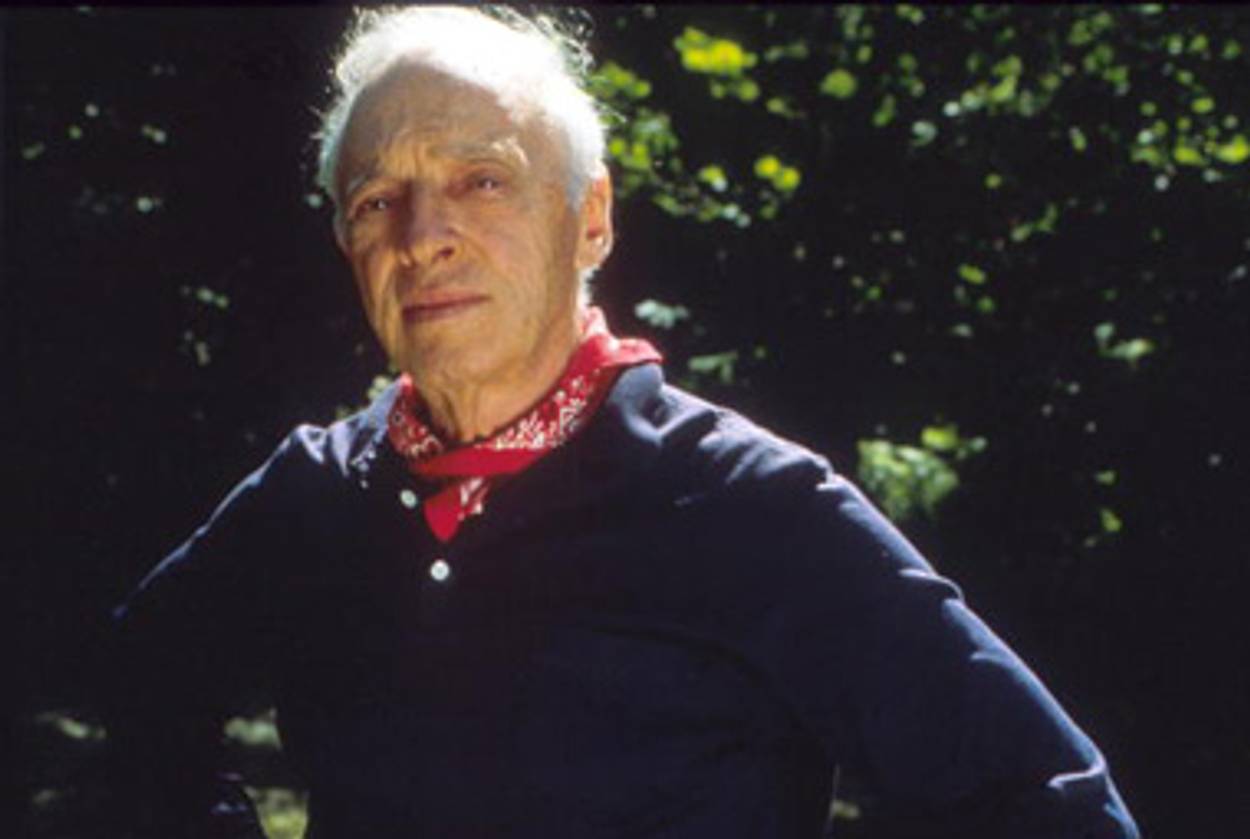

Pen Pal

In his letters, Saul Bellow was thoughtful, eloquent, feisty—and quite possibly at his most Jewish

“I have ever been unideological. I have sophisticated skin and naïve bones.” Thus wrote Saul Bellow in 1955, four days after turning 40, to Leslie Fiedler, a guy he didn’t have too much time for, but for whom he nonetheless took a moment to disassociate himself from the Partisan Review crowd and their knee jerk leftism. And for anyone else who might have wanted to claim him for one cause or another during his long life here he is again, writing to Martin Amis 35 years later: “The likes of us should quit politics and stick to dreams.” Like Yeats, Bellow was caught in the cold snows of a dream from the moment he first put pen to paper, but then there were all the interruptions: wives who wanted to make a mess out of him, wives who didn’t, girlfriends, children, law suits, the odd literary battle, travel, illness, prizes, and when the latter piled up self-protectively saying no, repeatedly, but not exclusively, to requests for appearances, comments, lectures. Writers want to write, or at least they used to, before they wanted to be on The Colbert Report.

Saul Bellow’s letters, the last reproduced in the newly-released Saul Bellow: Letters written in February 2004, a year before his death, already have an antique flavor. They are beautifully wrought dusty figures in the carpet before the avalanche of emails and tweets that await us. Which is not to say that the letters aren’t vital and combative, no punches pulled from beginning to end. He starts early on in adult life bashing Mary McCarthy, and at 83 he’s still got the balls to let Philip Roth know what’s wrong with I Married a Communist. But honesty for Bellow is almost always a measure of friendship. And if you dish it out you have to be ready to take it; and take it he does. Sadly, we can’t get his correspondents’ p.o.v., but we deduce from Bellow’s replies who’s swinging for him and who isn’t.

The correspondence he seems to enjoy best is with familiars attuned to the old neighborhood, whether in Montreal or Chicago, like the Trotsky scholar Albert Glotzer. Here he can reach back, as Moses Herzog does in some of the most haunting passages in Herzog, to evoke bitter winters “the zero teeth of Chicago eating at my toes” and skating on Humboldt Park lagoon, “One pair of skates had to do for all three boys.” Something more than nostalgia is on the table here: “I wonder what it is that so fascinates us about the old city. I suppose we had instinctively understood that it filled our need for poetry.” That’s a Bellovian moment, the swerve into an understanding of how intrusions of beauty arise in unlikely places.

Glotzer was a Trotsky scholar, but it was Bellow who was among the first people to see the great revolutionary dead “with a bloody turban of bandages and his face streaked with iridescent iodine.” That remarkable flash of history arrived while Bellow, posing for the moment as a newspaperman, was visiting Mexico in the summer of 1940. His description is dropped laconically into a letter in a manner that is of a piece with a number of “wow” moments in this collection: dinner with Marilyn Monroe, “I have yet to see anything in Marilyn that isn’t genuine. Surrounded by thousands she conducts herself like a philosopher.” An audience at Downing Street with the Iron Lady Margaret Thatcher, “American friends have asked me for my impressions: ‘Well you’re cruising on an interstate highway and a few hundred feet ahead you see a perfectly ordinary automobile … and then suddenly it turns on its dangerous blue police lights and you realize that what you took for a perfectly ordinary vehicle is packed with power.’ ” It’s not the celebrity brush that matters, Bellow’s a celebrity himself, but the refined consciousness brought to bear on the person or place under scrutiny.

Time passes, and the letters only get feistier. The by-now-infamous dinner with Christopher Hitchens and Martin Amis in which swords were crossed over an Edward Said article in Critical Inquiry is reprised and rehearsed in a letter to Cynthia Ozick, and it is one of the late, high directional markers on the long Jewish trail that meanders throughout this collection. For Bellow, Hitchens is a “Fourth Estate playboy thriving on agitation, and Jews are so easy to agitate.” It is clear from the letters, especially those written to his friend the novelist John Auerbach, a survivor of Stutthoff concentration camp who lived on Kibbutz S’dot Yam, that Bellow loved Israel, warts and all, and also that he felt a certain anguish that he had largely elided the Holocaust in his work until Mr. Sammler’s Planet. Is he more heart-on-his-sleeve Jewish in his letters than in his novels? Yes. The letters are flecked with snowflakes of Yiddish, and he even confesses that at one point, early in his life, he “had to decide … whether to write in English or in Yiddish, and when I opted for English the Yiddish began to wither.” But Bellow’s Jewishness, like the character of many of his protagonists, is frequently defined in opposition or quirkily outside the mainstream. There’s an extraordinary letter to Stephen Mitchell, written after Bellow had read Mitchell’s The Gospel According to Jesus: A New Translation and Guide to His Essential Teachings for Believers and Unbelievers, which records Bellow’s hospitalization in Montreal as an 8-year-old during which he nearly died and how he came to be “overwhelmed” by Jesus while reading the New Testament. “Jesus moved me beyond all bounds by his deeds and his words. His death was a horror to me. And I had to face the charges made in the gospels against the Jews, my people. Pharisees and Sadducees. In the wards, too, Jews were hated. My thought was (I tell it as it came to me then): How could it be my fault? I am in the hospital.”

Bellow, as evidenced in the letters, doesn’t have much time for Freud, a “nudnik” who “subjugated us with powerful metaphors.” (What would Freud, one wonders, have done with Bellow’s dream, recorded in a letter to Martin Amis, in which a secret remedy for a deadly disease is inscribed in Chinese on his penis?) But nonetheless, after all the high thought, wonderfully acerbic judgments, antic letters to poets and fellow novelists, generous pleas to find grant money for other writers, poems to lovers (not so good), and lyrical evocations of place, particularly Vermont, it is childhood scenes and their psychological residue that affect this collection with most force. Hence, the poignant letter to his friend the Chicago writer Eugene Kennedy, the last collected in this book, which returns to that place where all the ladders start: “My parents wanted me to grow up in a hurry and that I resisted, dragging my feet. … We often stopped before a display of children’s shoes. My mother coveted for me a pair of patent-leather sandals with an elegantissimo strap. I finally got them—I rubbed them with butter to preserve the leather. This is when I was six or seven years old, a little older than Rosie [Bellow’s daughter] is now. Amazing how it all boils down to a pair of patent leather sandals.”

The legacy and fate of the 20th century’s great white male novelists is not yet clear to us. D.H. Lawrence’s party, for example, has become a distinctly ill-attended affair. Benjamin Taylor has done a superb job in both his selection and his introduction to these salient letters from a gone world when literature was all the rage.

Jonathan Wilson is the director of the Center for the Humanities at Tufts University. His books include the novel A Palestine Affair, the story collection An Ambulance is On the Way, and, from Nextbook Press, the biography Marc Chagall.

Jonathan Wilson is the author of eight books including the novel A Palestine Affair and a biography, Marc Chagall. He recently completed a novel, Hotel Cinema, about the unsolved murder of Chaim Arlosoroff.