Understanding the Real Origin of that New York Times Cartoon

How antisemitic Soviet propaganda informs contemporary left anti-Zionism

A black-and-white photograph from the 1970s [Fig. 1] shows happy Soviet children at a May Day parade. They are hitching a ride on a parade installation: a giant hook-nosed spider wearing a military cap adorned with the Star of David, its teeth bared in a sinister grin. Massive rods under its legs suggest both the spider’s web and the meridians of the globe it is trampling. The accompanying slogan offers the proper ideological lens: “Zionism is the weapon of imperialism!”

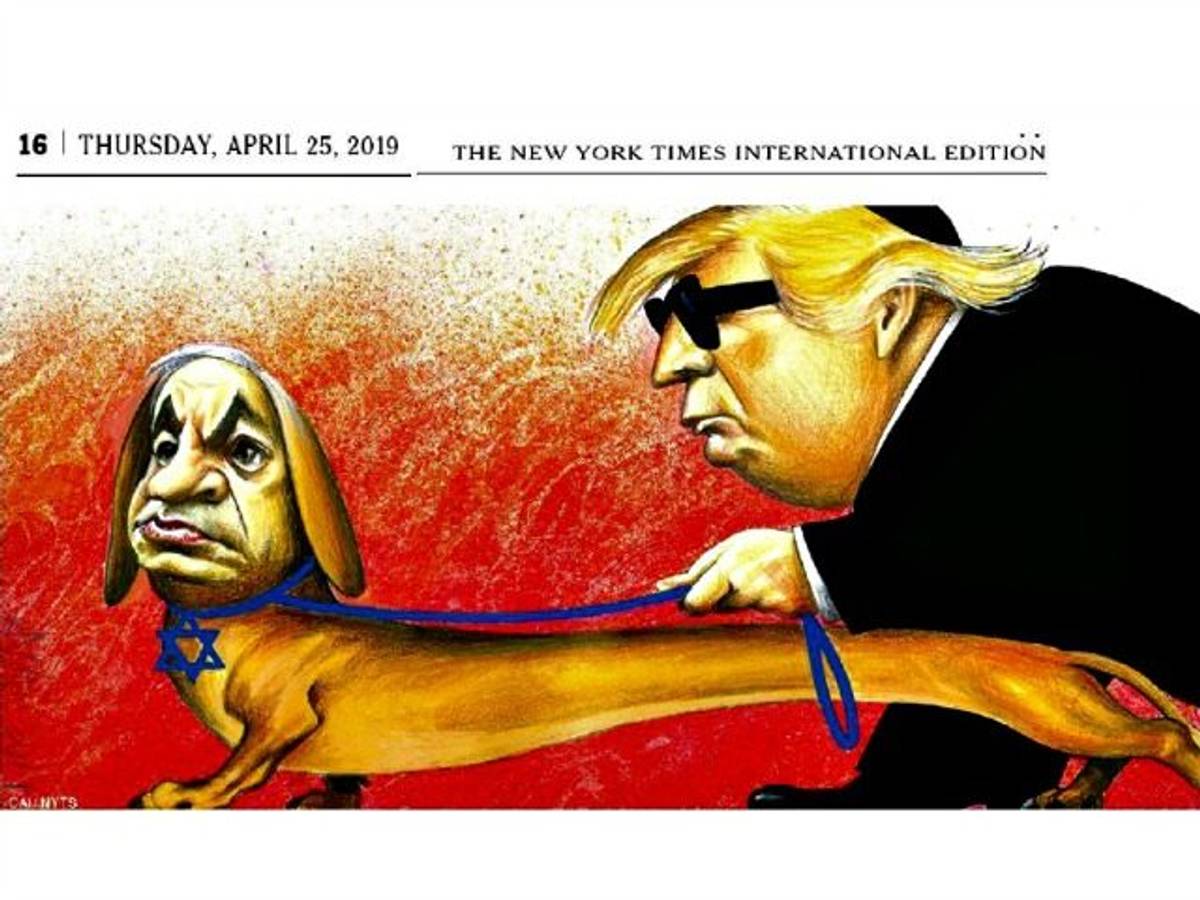

It was this image that popped into my mind the day of the infamous New York Times’s cartoon [Fig. 2] of a short-legged guide dog Jew with the face of Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, a Star of David medallion dangling from its collar, dragging a blind kippah-wearing Donald Trump.

The outrage the Times’ cartoon produced was appropriate, but interpretations of what had happened fell short. Was the cartoon truly a lineal descendant of the anti-Semitic propaganda published in Der Stürmer, as some reflexively opined? To stop there was to accept the possibility that the offices of the New York Times’ international edition are packed with white supremacists. Even if a single production editor was responsible for the incident, as the paper asserted, the publisher’s decision to put the entire staff through sensitivity training to address “unconscious biases” would suggest that senior management was worried others in the company might be similarly infected. Yet the idea that the Times is infested with neo-Nazis seems patently silly.

What makes more sense is the possibility that the cartoon made it into print because the paper’s staff—whether singular or plural—saw it as “a political issue and not religious,” in the words of António Moreira Antunes, the artist who drew it. Like the slogan on the Soviet May Day parade installation, the face of the Israeli prime minister must have signaled to the New York Times staff that the cartoon was about Israel and therefore political—anti-Zionist perhaps, but not anti-Semitic.

Yet the conventional wisdom on the left that anti-Zionism is easily distinguishable from anti-Semitism has run into some obvious practical difficulties in recent months as the Women’s March, the U.K. Labour Party, Congresswomen Rashida Tlaib and Ilhan Omar, Marc Lamont Hill, and AJ+ Arabic, Al Jazeera’s popular online platform, have all shown an inability to distinguish between what they consider to be anti-Zionist political positions and overt anti-Semitism.

So if anti-Zionism and anti-Semitism are not the same, why is the left doing such a poor job of distinguishing between the two? How is it that the side of the political spectrum that makes anti-racism one of the central tenets of its platform repeatedly stumbles into espousing such vile hatred?

The left would be less confused if it were able to soften temporarily its ahistorical, ideologically driven focus on the right as the sole source of anti-Semitism and devote some time to studying its own rich history of the same. In particular, it should look at the Cold War-era Soviet Union, which for decades not only practiced politically weaponized anti-Zionism but also exported it abroad. Many of the core tropes that animate the anti-Zionist left today are carbon copies of ideas that the KGB and the Department of Propaganda’s ideologues developed, weaponized, and popularized with particular intensity in the wake of the Six-Day War. It is there, not among the Nazi oeuvre, that the direct precursors to the New York Times cartoon and similar such efforts, in which the European press has been awash for the past two decades, are to be found.

The history of Soviet anti-Zionist cartoons makes obvious that separating anti-Zionism from anti-Semitism can be a challenging if not impossible task. Produced by a system that claimed to have rejected anti-Semitism, and labeled as anti-Zionist, the cartoons nevertheless retained a powerful anti-Semitic charge. So did the rest of the propaganda that the Soviets produced as part of their demonization of Israel and Zionism that began with Stalin’s postwar show trials and continued with varying levels of intensity through the end of the USSR.

Soviet anti-Zionist propaganda entered a particularly active stage following the Arab-Israeli Six-Day War in 1967. The propaganda and disinformation campaign that the Soviets developed then, which demonized Israel and Zionism, served their specific domestic and foreign interests and was aimed both at domestic and foreign audiences. It was most likely this latter stage of Soviet anti-Zionism that forged in popular consciousness on the far left false links between Zionism and Nazism, fascism, racism, genocide, settler-colonialism, imperialism, militarism, and apartheid. The ideas from this campaign were actively used in the Soviet promotion of the “Zionism Is a Form of Racism” resolution adopted by the United Nations in 1975. And it is this campaign that refined and popularized the particular Holocaust distortion narrative that remains so popular in certain anti-Semitic and anti-Israel circles—the kind that was recently broadcast to millions by AJ+.

The Soviet anti-Zionist campaigns produced hundreds of books and thousands of articles smearing Israel, Zionism, and, with them, Judaism and the Jewish people. Newspapers with a circulation in the millions carried these writings to every corner of the USSR. A different set of publications, with similarly million-copy circulations, published in some 80 foreign languages, carried these messages to the West and Third World countries. So did radio broadcasts, which in the early 1970s transmitted some 1,000 hours of Soviet propaganda weekly to every continent on the planet.

Soviet ideology didn’t allow the Soviets to propagate outright racist anti-Semitism of the Nazi variety. They rejected accusations of anti-Semitism, claiming that their ideology was anti-Zionist, not anti-Semitic. In developing their ideas, Soviet ideologues relied for inspiration on the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, on the ideas of classic religious anti-Semitism, and even Mein Kampf, but adopted them to the Marxist framework by substituting the idea of a global anti-Soviet Zionist conspiracy for a specifically Jewish one. Jewish power became Zionist power. The rich and conniving Jewish bankers controlling money, politicians, and the media became the rich and conniving Zionists. The Jew as the anti-Christ became the Jew as the anti-Soviet. Instead of the Jew as the devil, they presented the Zionist as a Nazi.

In practice, the distinction between Soviet anti-Zionism and anti-Semitism often proved a distinction without a difference. The tropes were the same, albeit with a new set of labels. Jews living in the Soviet Union saw their culture and religion decimated, educational and professional opportunities depleted, and became licensed targets of casual grassroots anti-Semitism.

Soviet anti-Zionist cartoons relied on a particular set of symbols to identify “the Zionist” as an object of contempt and hatred. Since one of the political goals of Soviet anti-Zionist ideology was to undermine Israel, Soviet caricaturists typically depicted a “Zionist” as wearing Israeli military uniform. When it came to identifying a Jew as such, they used the full arsenal of anti-Semitic portrayals developed over the centuries. One traditional approach was to show a Jew as subhuman in form (a dog, a spider, an octopus, a snake) yet in possession of supernatural powers. The “Zionists” were invariably drawn with stereotypical Jewish facial features—a classic tool of traditional anti-Semitism—to make sure that it was clear who the artist had in mind.

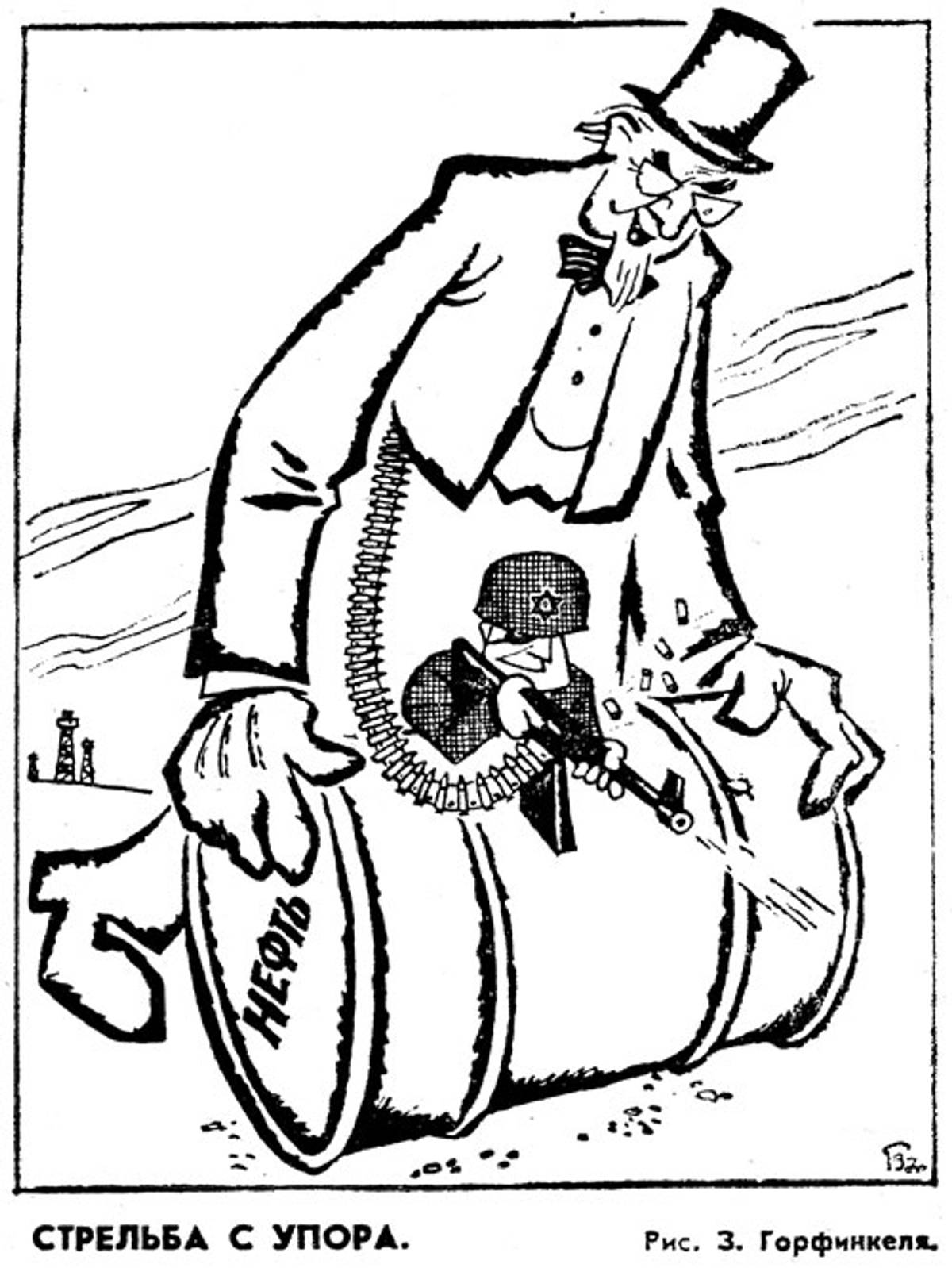

One of the forerunners to the guide dog in the New York Times cartoon is the Soviet Israeli-Zionist dog who loyally served its master, the imperialist Uncle Sam. The smallness of the dog signals its contemptibility. For example, the tiny attack dog in this 1969 image [Fig. 3] is barking mad, dropping bombs instead of saliva at the behest of its American master. The dog wears an Israeli military uniform, but the viewer also knows that the dog is a Jew because of its Jewish facial features. The uniform makes the Jew—and by extension, any Jew—a fair game for demonization.

The concept of a Jew-Zionist as a stand-in for Israel who drags the United States toward a destination of its choice—the core idea of the Times’ cartoon—appeared frequently in Soviet caricature. In this figure [Fig. 4], a Jew-Zionist’s hand guides the United States to drive a nail into the Arab lands already branded with a Star of David. The hammer has a dollar sign on it—a frequent motif in Soviet caricature invoking the familiar anti-Semitic trope of Jews and greed. In this one [fig 5], an Israeli Jew with a gun is riding on a barrel of oil as he leads the United States into war.

The goal of these cartoons was to demonize Israel and Zionism. But the use of stereotypical pejorative signifiers of a Jew showed whom its intended audience would find at fault: any Jew it came in touch with.

The kind of Jew-spider we saw in the photograph from the 1970s was another frequent figure in Soviet caricature. The Jew as spider is a timeless trope in the anti-Semite’s arsenal, once gracing the cover of a French edition of the Protocols of the Elders of Zion [Fig. 6]. (Note that here the Jew is not a Zionist but a Judeo-Bolshevik, which illustrates the eternal ideological flexibility of the anti-Semite.)

The Soviets put this golden oldie to their own use. One of the best-known Soviet images of this kind is titled “A Zionist Cobweb Spider: at his favorite work” [Fig. 7]. The spider has stereotypical Jewish features, a contemptible posture, and an aggressive scowl. The word “Zionism” graces its back. Its web has the Star of David at its heart and is made up of calumnies, lies, anti-Soviet attitudes, “the Jewish question,” and anti-communism—words written along the meridians of the web. The vile anti-Semitic quality of this image is obvious, and the “Zionist” labeling does nothing to reduce it.

Jew as a vile and deadly snake is present in Soviet propaganda as well. Fig. 8 shows an aggressive, hook-nosed snake riding on a barrel of oil labeled “U.S. oil monopolies.” Like the snake on a different cover [Fig. 9] of the Protocols, this Soviet anti-Zionist snake has stereotypical Jewish facial features and Stars of David drawn along its body. Both the Jewish-conspiracy snake and the Zionist-conspiracy ones threaten to suffocate the world—the Protocols one literally, and the Zionist one by depriving the world of vital energy resources. In Fig. 10, the snake has a gun in place of a tongue and the word “Zionism” written on its body. The caption, “ExpanSIONISM in real life,” is spelled in such a way as to play on words: “Sionism” is the Russian for Zionism.

But perhaps the most disturbing and consequential set of Soviet anti-Zionist cartoons were ones that sought to tie Zionism and Nazism together—a link that remains alive and well on today’s anti-Zionist left. While the comparison itself dates back to the 1930s, it wasn’t until the Soviets launched their post-1967 anti-Zionist campaign that it became truly developed and popularized at home and abroad. It was this parallel that, in the words of William Korey, helped transform Zionism into “the bête noire of the international community,” turning Zionism into a representation of evil incarnate.

The caricatures helped to make this connection visceral. They did so with the help of several sleights of hand. One was to juxtapose, associate, and even merge the swastika with the Star of David [Fig. 11]. Here the Star of David and the symbol of one of the greatest evils to befall humanity literally become one. This approach is still used widely on the anti-Israel left, as in the picture of the Israeli flag that appeared in the leftist Daily Kos blog [Fig. 12].

Another was to present the Nazis (often Hitler himself) as a mirror image or shadow of the Jew-Zionist. One of the most striking caricatures of this style is shown in Fig. 13, which depicts a middle-aged man with stereotypical Jewish features holding an ax dripping with blood. Making the image even more sinister is its cast shadow, which takes the form of Adolf Hitler’s silhouette. The Star of David on the Jew’s ax becomes a swastika in the shadow. This cartoon is particularly interesting because the Jew in it has neither Israeli military uniform nor any of the other typical signifiers by which he might be labeled a “Zionist.”

Here the very faint line between anti-Zionism and anti-Semitism is completely erased. The caricaturist is honest: It is about Jews, not “Zionists.” As the Dutch researcher Judith Vogt noted in her 1984 essay “When Nazism Became Zionism: An Analysis of Political Cartoons,” “Hitler’s shadow evokes the Jew’s reputed gift of mimicry—of always being able to change his identity.” This shape-shifting ability is commonly attributed to Satan, to whom Jews were frequently compared by religiously motivated anti-Semites. Here, as with other aspects of classic anti-Semitism, the Soviets adapted a well-worn concept for their own purposes.

In Fig. 14, Hitler’s face, drawn inside a Star of David, looks almost childish and innocent, whereas the very real, obviously Jewish Israeli soldier has blood dripping from his weapon and scenes of destruction in the background. In figure 15, an Israeli soldier and a Nazi German soldier each hold a gun and pose in the same way before a scene of devastation. But the Nazi German figure is a museum painting in a frame, rendering him harmless. The Israeli Jew, on the other hand, is real and therefore the more dangerous.

A specific subset of Soviet propaganda, including caricatures, sought to explicitly connect with Zionism concepts that the Soviet people, as well as Western audiences, already associated with Nazi Germany. In Fig. 16, an Israeli Jewish soldier is holding a weapon that has the word Blitzkrieg written on it. He is standing next to a signpost painted as an Israeli flag and bearing the word Lebensraum—a clear attempt to equate Israel’s 1967 territorial conquests with the Nazi conquest of Soviet territories. In front of the soldier is a deathlike figure dressed in Nazi uniform showing the soldier a picture of an Auschwitz crematorium, with New Order written on it. Here, too, the Nazi is reduced to a mere shadow of his former self. His characteristics and ideology are now conferred on the Israeli Jew.

According to Israeli scholar Yeshayahu Nir, who analyzed Soviet caricature in his book The Israeli-Arab Conflict in Soviet Caricatures 1967–1973, most of the time these caricatures were published in mass-circulation newspapers without any overt tie to events. The same image could be reprinted days, weeks, or years later without any changes or connection to political developments. Their objective was propaganda, not information or commentary. The goal was not to criticize Israeli policies; it was to demonize the country and everything it represented.

Foreign-directed Soviet anti-Zionist propaganda gradually built in for its audiences associations between Israel and such familiar Nazi German-specific terms as genocide, concentration camps, deportations, and Lebensraum. Israeli scholar Baruch Hazan documented this progression. By 1969, he wrote, the concept of “Zionist racism” was in active circulation in Soviet press materials directed abroad. By 1971, it was linking the Nazi phrase “master race” to the Jewish religious concept of a chosen people. (This idea would gain particular notice in the global community when it featured prominently in a major speech in the Security Council by the Soviet ambassador to the U.N., Yakov Malik.) Later still it added the idea that Zionism practices racism against anti-Zionist Jews everywhere.

“While stories of Israeli cruelty are broadcast indiscriminately by Moscow, … concepts such as ‘Nazism,’ ‘concentration camps,’ ‘

Gauleiters,’ ‘Herrenvolk,’ etc., are used mainly in articles and broadcasts aimed at European audiences,” wrote Hazan. “‘Racism,’ ‘discrimination,’ and plain sadism are reserved for African audiences, which are generally not acquainted with Nazi terminology. Stories about racism practiced against all Jews who oppose the Zionist idea are directed at places where, in fact, there are practically no Jews—such as Southeast Asia.”

These ideas and images continue to permeate the anti-Zionist discourse on the far left. They are also evident in the anti-Zionist caricature of today: from a Jew viewing his mirrored reflection as Hitler [Fig. 17], to a comparison of the West Bank and Gaza territories to Auschwitz [Fig. 18], to the use of the swastika to denote the State of Israel [Fig. 19].

The contemporary left needs to understand that Soviet history is its history. Just as the right needs to take responsibility for the historical and emotional meanings of the buzzwords and images it deploys, the American far left has its own soul-searching to do: according to the historian Stephen Norwood, many of its predecessors rationalized or simply ignored Soviet-style anti-Semitism. Some even defended it.

Today, the often-voiced idea that today’s far-left anti-Semitism is merely “political” and therefore benign is rapidly losing its already-thin credibility. No one doubts that there are white supremacists who are armed and ready to kill. But what is the impact of an anti-Semitic image published in one of the world’s most widely circulated and respected newspapers?

Anti-Semites recognize anti-Semitism no matter what side of the aisle they live on. It is no accident that Holocaust denier David Irving expressed admiration for the self-described anti-racist Jeremy Corbyn and white supremacist David Duke did the same for Ilhan Omar. This approval should cause the far left to ask itself some difficult questions about the role its own tropes may play in the murders executed by the far right, in the ongoing wave of hate crimes against Jews being committed by non-white assailants in New York and other cities, and in the mainstreaming of openly anti-Semitic discourse behind the fig leaf of anti-Zionism

Izabella Tabarovsky is a Tablet contributor. Follow her on Twitter @IzaTabaro.