Beat the Clock

The White House has put the squeeze on Iran with a serious sanctions regime in the past few months. But for Israel, it may be too little, too late.

From an American perspective, it seems that the White House has finally gotten serious about bringing the Iranian nuclear program to a halt. After President Obama’s policy of engagement came up empty, the administration, pressed by Senate leaders, finally implemented sanctions against the Central Bank of Iran and the Iranian energy sector on Dec. 31 and then leveled more sanctions against the bank earlier this month. The sanctions have sent the Iranian currency into freefall.

The squeeze continues: This month, Congress pressured the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication, which provides tens of thousands of financial institutions with a system for transferring money around the world, to block Iranian institutions from using the service. SWIFT announced last week that it “stands ready to act and discontinue its services to sanctioned Iranian financial institutions as soon as it has clarity on EU legislation currently being drafted.”

From the American point of view, all this is a clear sign, as Defense Secretary Leon Panetta said recently that “The United States … does not want Iran to develop a nuclear weapon. That’s a red line for us.”

But for Israel, this still falls way short of the mark.

If you want to understand how the Jewish state sees the nascent Iranian nuclear arms program, you need to stop thinking like a superpower with vast resources that inhabits a virtual island several thousand miles from the Persian Gulf—and start thinking like a tiny state with limited resources, formed in the aftermath of the Holocaust, and within ballistic missile range of Iran. You’re going to go along with your American patron as far as you can, but in the end, you’re going to keep your own counsel.

***

Last month at the annual Herzliya conference, which brings Israel’s top political, military, and security echelons together with their colleagues from around the world, the majority of Israeli officials and analysts I spoke with said they believe the sanctions have come too late. Perhaps five years ago, economic suffering might have forced the Iranian regime to reconsider its plans. But now with Iran enriching uranium to 20 percent, moving it closer to producing weapons-grade uranium, and even Panetta admitting that the Iranians are a year away from building a nuclear weapon, there are two choices: Either accept that the Islamic Republic has joined the nuclear club, or bomb the country’s nuclear facilities in the hope of setting the program back, at least by a few years. If it’s become increasingly clear to Israel that the Obama Administration is not going to take military action, the question is: When does Israel pull the trigger?

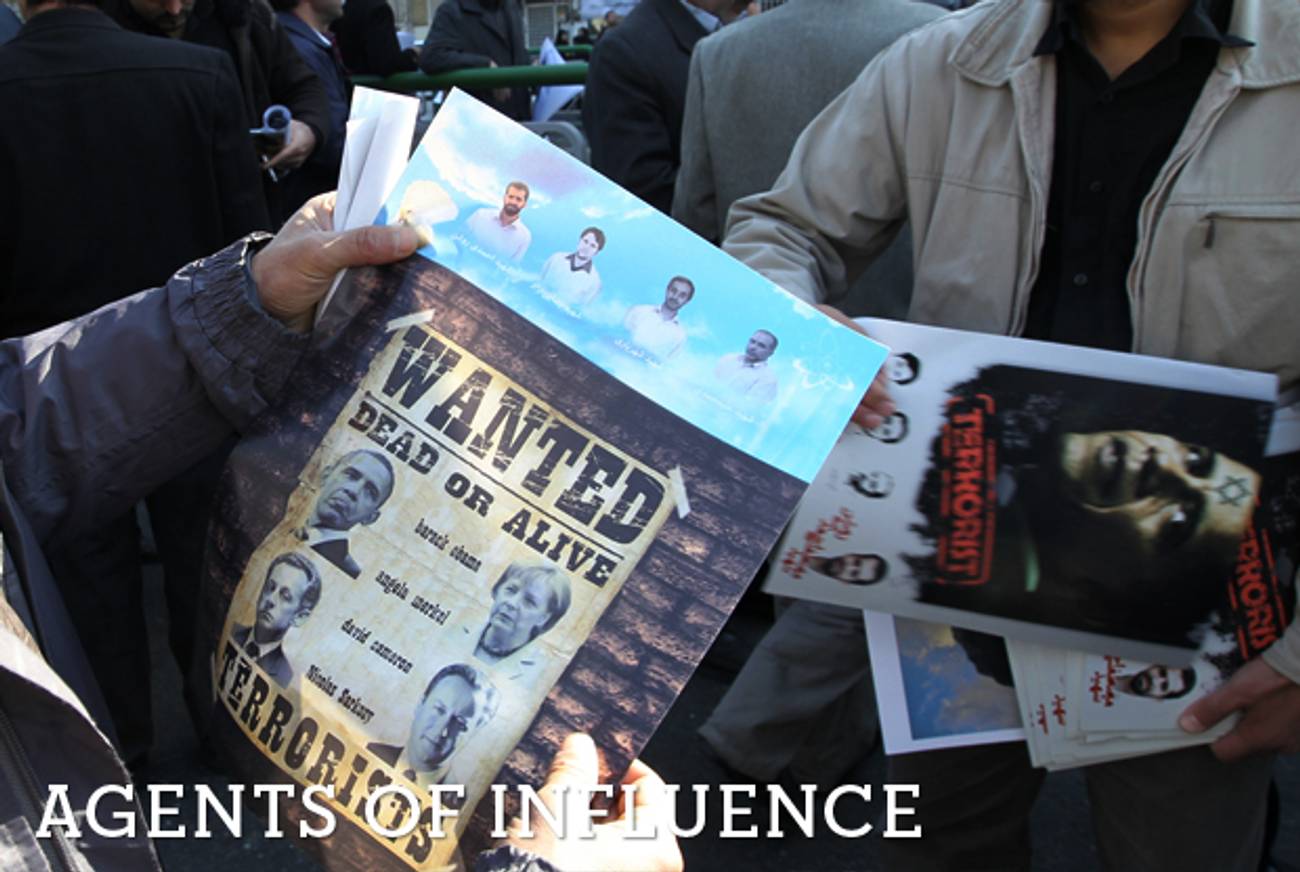

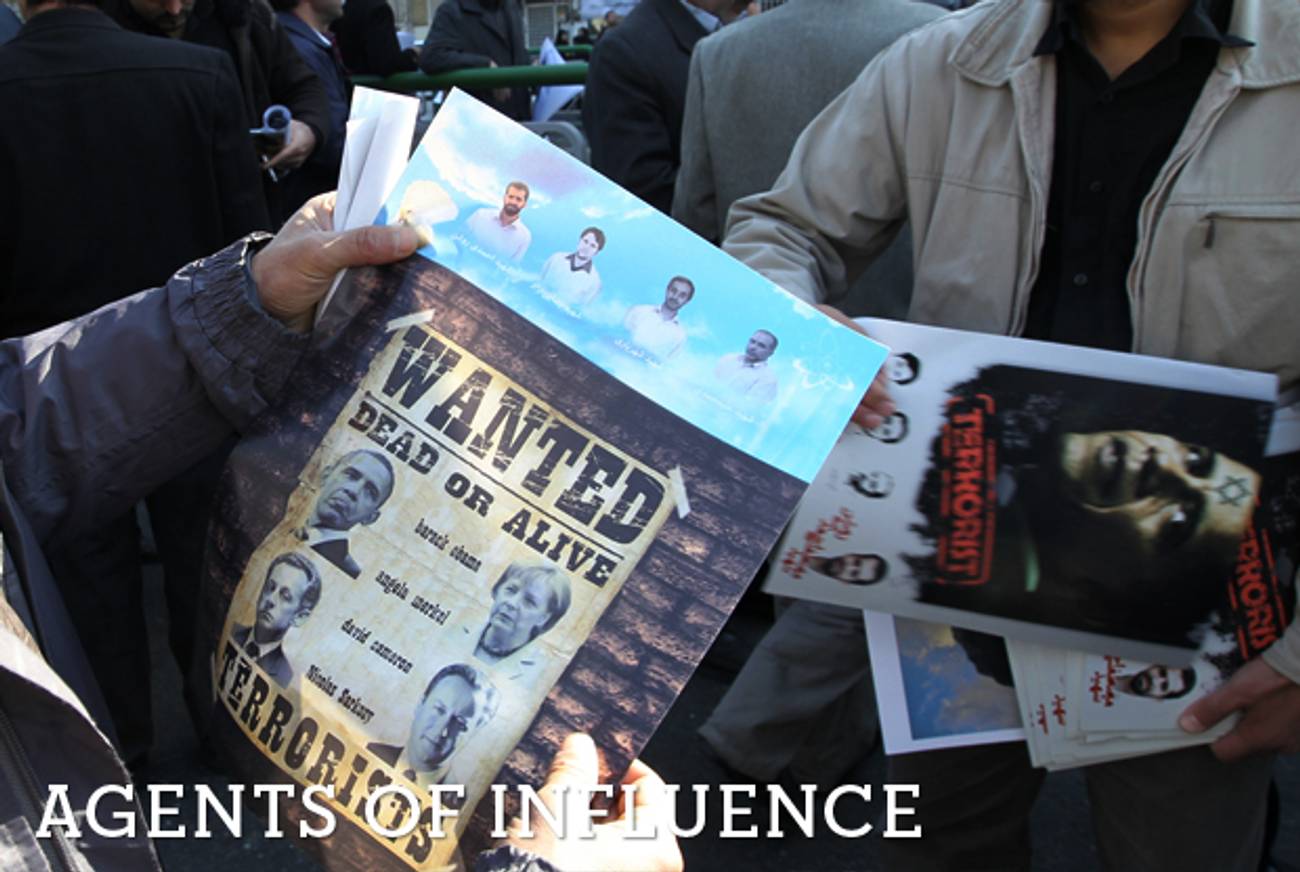

Some experts make the case that Israel’s war against Iran’s nuclear program is already well under way. “Over the last decade Israel has spent a lot of money to prepare for all sorts of options on Iran,” David Wurmser, formerly Vice President Dick Cheney’s Middle East adviser, told me this week. Such options include computer worms, like Stuxnet, and covert operations, like the assassination of nuclear scientists and sabotaging military installations, as well as possible commando raids and air raids.

Now the head of a consulting group called Delphi, which has a few sensitive projects in Israel, Wurmser says it is crunch time for Israeli leaders. He’s seen a marked shift in Israel’s security establishment over the last few months. Perhaps the surest sign is that President Shimon Peres, not typically perceived as a hawk on Iran, has begun warning that a nuclear Iran poses an existential threat to Israel and is “a real danger to humanity as a whole.” Said Wurmser: “It’s not just about Bibi and his historical legacy anymore. He doesn’t need to be a leader in a Churchillian mode, because the consensus on attacking Iran is broad based.”

Up until last summer, Wurmser told me, the overriding sentiment among Israeli leaders was to give the Americans time. “Some thought that the sanctions might work, while others merely wanted to be patient in order to manage the White House in the aftermath of an attack,” he explained. But for Israel, there are other timelines to consider besides Iran’s ability to manufacture a bomb. In addition to its own budgetary concerns, most significant for Israel is Iran’s defensive capability, including advanced Russian anti-aircraft systems that the Iranians reportedly purchased a few years ago. Wurmser contends that “the Russians never actually sold that system to Iran, or anything that was significant.” However, Moscow’s decision to take a strong stand against the United States by backing Iran’s client, Syrian President Bashar al-Assad, indicates that Russia is moving more aggressively against Israel and the West—and Jerusalem is sensitive to such geopolitical shifts.

Wurmser is among the few analysts who thinks that Israel is capable of setting the Iranian program back. But he believes the operation isn’t going to look like what people expect. Wurmser points to Israel’s history of innovative warfare and says it wouldn’t be a surprise to see the same pattern in a strike against Iran. “We might see really weird things, like one-way drones, Doolittle-raid type stuff, where pilots return but the planes don’t. That would mean ditching some really expensive aircraft but you need to consider what are the out-of-the-box crazy things Israeli planners might think of. No one thought Entebbe was possible, or that F-16s could be used to attack Osirak [Iraq’s nuclear reactor].”

That is, to understand what Israel might do, don’t think like a superpower. “The American debate over Israel’s ability to hit Iranian facilities is dominated by analysts who come from the U.S. Air Force,” said Wurmser, a former U.S. Navy intelligence officer. “There the idea is the utter destruction of infrastructure. And so their question is whether Israel can hit hardened targets. But you don’t need to.”

Instead, according to Wurmser, the issue is whether Israel knows precisely what targets to hit in order to destroy Iranian centrifuges. “If they’re not powered down properly, the cascade is destroyed. So, presumably Iran has hardened the power supplies and put generators in tunnels. But you don’t need to destroy the tunnels, only seal them off so that the lack of air shuts down the generators. It’s sort of a sophisticated way of putting a banana in a tail pipe.”

As Wurmser sees it, what Israel needs to make an attack work is not ordnance, but intelligence, which is what the Israelis have been gathering in their ongoing covert war against Iran, assassinating Iranian nuclear scientists and sabotaging military facilities. “The Israelis have mastered an intelligence loop,” said Wurmser. “The intelligence provides a target, like a nuclear scientist; and the Iranians respond by hardening other sensitive targets, which restarts the intelligence process, like a constant interactive circle.”

Reuel Marc Gerecht, a former CIA case officer, is far less confident of Israel’s ability to gather intelligence in Iran: “It is beyond Israel’s capacity to sustain a team inside Iran. There are problems with visas, security. They could bring in people on a short-term basis, run conservative operations and meetings, and bring some supplies in, but I’m not 100 percent convinced that all the attacks can be traced back to some type of Israeli effort.”

Some of the assassinations of Iranian scientists, Gerecht believes, were likely carried out by domestic opponents of the regime, perhaps working in tandem with Israel. And the major explosion at an advanced missile-research center in the desert near Tehran in November might well have been an accident. “The Iranians are extremely careless,” he told me. “We know it by watching them at war, how they handle the production of machinery and war materiel, how they handle themselves in clandestine operations. What they have going for them is that they just persevere.”

Gerecht says that the Israeli officials he’s spoken with contend that the “unnatural events” occurring inside Iran are indeed a sign that the war’s already begun, but Gerecht is skeptical. “In the big scheme of things, these operations are not that impressive, given how far advanced the Iranian program is. Like almost all covert operations, it’s too little, too late: They don’t have the scale to effect a program like this. In some sense, these operations signal the absence of war. They’re not doing it to soften Iranians for a big attack. It’s operational procrastination. When you don’t want to get involved in a military conflict, you go to covert action and special forces.”

Of course, it may also be that Israel’s secret war is also a psychological operation, destined to drive the regime to distraction and force its hand. And of late, Iran has warned that it will take preemptive action if its interests are threatened. If the Iranians do act out,

Israel might enjoy the luxury of being well-prepared for a hot conflict it doesn’t actually initiate.

Lee Smith is the author of The Consequences of Syria.

Lee Smith is the author of The Permanent Coup: How Enemies Foreign and Domestic Targeted the American President (2020).