Needle Points

Chapter II: The kernel brilliance of vaccines

The kernel idea of exposing a person to a weakened form of a pathogen or toxin, known colloquially as “like to treat like,” long preceded modern medicine, and came in stages and through observation. Paracelsus, who was said to have treated persons during a plague in 1534, noted that “what makes a man ill also cures him.” During the ancient plague of Athens (430-425 BCE), the historian Thucydides noted that those who, like himself, got the plague and then recovered, never got the plague again. Chinese writing alluded to inoculation in the 10th century, and in the 16th century, Brahmin Hindus were inoculating people with dried pus from smallpox pustules. Similar practices, which were common in Turkey in the 1700s, were brought to England by the remarkable Lady Montagu, the English ambassador’s wife. But when some, such as King George III’s son, died on being inoculated with the smallpox, many became reluctant to undergo the procedure.

A key advance occurred when farmers in England in the 1700s noticed that dairymaids who milked cows got “cowpox” on their hands from the udders. Cowpox was a very mild illness compared to smallpox, which had a 30% mortality rate by some estimates. It was observed that the maids with cowpox were immune to the dreaded smallpox. An English cattle breeder named Benjamin Jesty, who had himself contracted cowpox and was thus immune to smallpox, decided—supposedly on the spur of the moment—to intentionally inoculate his wife and children with cowpox. They remained immune to smallpox 15 years later.

The English physician Edward Jenner, learning of this, began systematically exposing patients to cowpox, including an 8-year-old boy named James Phipps. He exposed James to cowpox and then exposed him to smallpox to see if he’d contract it (an experiment conducted quite obviously without informed consent). The boy survived, and was vaccinated 20 times without bad effect, said Jenner, who reported on the benefits of the procedure in warding off smallpox in a series of cases. He was initially ridiculed for the idea, but in the end prevailed. The phenomenon was soon called “vaccination”—from vaccinia, the Latin for cowpox virus species (vacca being “cow”).

Some have even wondered whether the ancient Western symbol for the medical arts and healing still used today, the Rod of Asclepius, a serpent wrapped around a staff, may itself be an allusion to the kernel idea that something dangerous can also protect; according to Greek myth, Asclepius was said to have healed people with snake venom, which can have some medicinal properties that were written about by Nicander. And, interestingly, the same image appears in the Torah, in Numbers 21:8: “And the Lord said unto Moses, Make thee a fiery serpent, and set it upon a pole: and it shall come to pass, that every one that is bitten, when he looketh upon it, shall live. And Moses made a serpent of brass, and put it upon a pole, and it came to pass, that if a serpent had bitten any man, when he beheld the serpent of brass, he lived.”

All of which is to say that the heal-harm paradox is a deep archetype in the human psyche. And it came not from Big Pharma but from everyday, often rural observations—one might even call them “frontline” observations about how nature works, and how the immune system behaves.

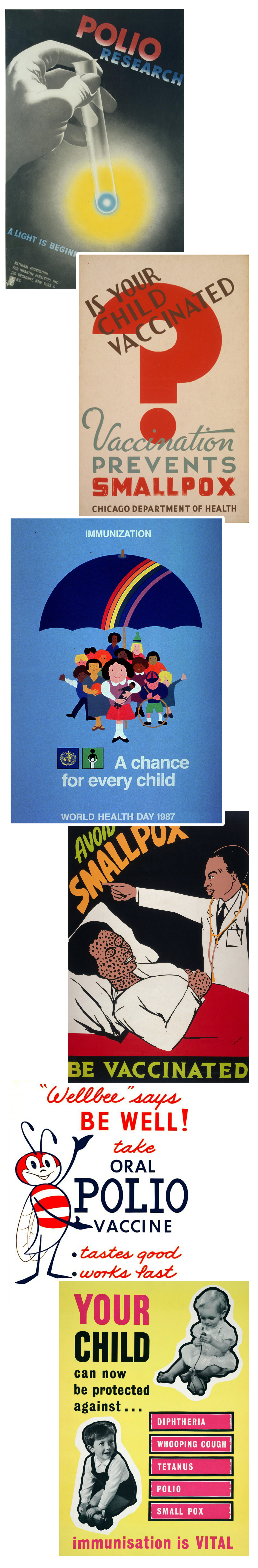

Among the great triumphs of vaccination are the elimination in the United States of the scourge of polio, and the eradication of smallpox throughout the world. Indeed, perhaps because of these successes, many of us nostalgically imagine that their development and public acceptance came easily. But the real history shows a more textured picture. A number of polio vaccines had to be tried. The initial vaccine studies had very little oversight, and the first vaccines left some children paralyzed. The first truly effective vaccine, the Salk, had problems too; in 1955, a bad batch of over 120,000 doses from the Cutter Pharmaceutical Company contained the live polio virus, causing 40,000 cases of polio and killing 10. “The Cutter incident,” as the event is now known, revealed the vulnerability of the systems that produce vaccines, and remains one of the sources of the nightmare that so haunts the hesitant: getting the dreaded disease from the treatment. The incident was followed by efforts to improve the regulatory systems so that similar tragedies wouldn’t be repeated.

In the public’s mind, perhaps the greatest triumph of vaccination was the midcentury worldwide eradication of smallpox—a horrifying scourge that was lethal in 30% of cases. The history as it is often told attributes the victory solely to vaccines, but as British physician Richard Halvorsen has written, it was not simply the product of a single “blockbuster” vaccine or campaign, as is so often described, but rather a regime of multiple public health measures instituted alongside vaccination.

The details here are quite interesting. Beginning in the 17th and 18th centuries, there were a number of mass campaigns of inoculation with smallpox, and then vaccination with cowpox, that led to a decline in smallpox in the 19th century. By 1948, some physicians in England thought the illness was sufficiently well-managed that mass vaccination of infants, which carried some risks, could wind down. And so mass vaccination was replaced by a new, more individually focused strategy: If a case was reported, public health officials isolated the person and their contacts, and the contacts were vaccinated. This was called “the surveillance-containment strategy.” It worked. After that cessation of vaccination in England, a few cases occurred there in 1973 and 1978—but both were based on laboratory accidents. According to Halvorsen, the World Health Organization came to the same conclusion and also adopted the surveillance-containment approach elsewhere. In 1980, the disease was declared eradicated.

But alongside the public health system’s triumphant eradication of polio and smallpox from the 1940s through the 1970s, there was a horrifying chapter as well—one that included staggering abuses by public health and medical authorities. The Tuskegee experiment, conducted by the U.S. Public Health Service (PHS) from 1932 until 1972, sent out representatives to find African American men with syphilis, who were told that they would receive treatment for their “bad blood.” No treatment occurred. The officials gave these men a placebo instead of penicillin, which would have saved them. This was done so the investigators, by watching the men die slowly, could study the natural course of the devastating disease.

During the same period of time, the U.S. public health system oversaw 70,000 sterilizations of “mentally deficient” people with learning problems, the blind, and the poor, and also forcibly removed the uteruses of African American and Indigenous women, all as part of an international eugenics movement that swept through public health. Psychedelics and other drugs were given to people in mental institutions without telling them, often leading to nightmare trips, and dangerous campaigns were undertaken based on only partial knowledge, such as the widespread radiation of healthy children’s thymus glands (a key part of one’s immune system), which later caused cancers. All these programs used abstract “population-based” thinking, dehumanizing people into numbers to be toyed with in the name of science and progress.

In the public’s mind, the greatest triumph of vaccination was the midcentury worldwide eradication of smallpox—a horrifying scourge that was lethal in 30% of cases.

None of the public health abuses during this period involved informed patient consent, and yet they were government-sponsored, lauded, and justified in the name of the greater good. It took the revelation of Nazi medical experiments on Jews and others to give rise to a new ethics of consent for research subjects. The Nuremberg Code of Ethics of 1947, along with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki originally developed by the World Medical Association, required physicians and scientists to obtain the informed consent of all research subjects. This breakthrough led to the normalization of patient consent not just for research subjects, but for those undergoing all medical procedures—and became a bedrock of what many of us in the medical field now see as an inviolable code of ethics.

But in the late 1970s and 1980s, there were new controversies. In 1976, a swine flu outbreak occurred at Fort Dix, New Jersey. Fearing that the country was on the cusp of a pandemic, the U.S. government approved a vaccine and undertook an aggressive rollout that involved 48 million people. But there were two unforeseen developments: First, the epidemic receded on its own, and rather quickly. Second, 450 vaccinated people came down with a neurological disorder called Guillain-Barré syndrome (in greater numbers than would be expected during that period).After producing and distributing the vaccine so quickly, the government then reacted with caution, but the idea that a vaccine could cause damage stuck in the public’s mind. “This government-led campaign was widely viewed as a debacle and put an irreparable dent in future public health initiatives,” wrote Rebecca Kreston in Discover, “as well as negatively influenced the public’s perception of both the flu and the flu shot in this country.”

That skepticism might have emerged so sharply because the swine flu “debacle” occurred against the backdrop of another contemporaneous event. In the 1970s a number of parents began arguing that their children were left with serious brain problems and seizures after receiving the diphtheria-pertussis-tetanus vaccine. Numerous vaccine-related lawsuits followed, and the parents scored many legal victories, costing pharmaceutical companies millions of dollars. It cost 12 cents to make a dose of the DPT vaccine in 1982, but within a few years, the cost increased 35-fold thanks to litigation awards, and as a result companies started leaving the vaccine business. To this day, there is disagreement about the primary cause of the brain problems, with some of the parents insisting it was the vaccine, and vaccine advocates arguing that these children actually had a genetic condition called Dravet’s syndrome, possibly brought to the surface by the vaccination, but which they would have suffered from anyway.

There is little disagreement, though, about what happened next. In 1986, the last pharmaceutical company still making the DPT, Lederle, told the government it would stop making the vaccine. Companies making vaccines for other diseases were also being sued, and also stopping production. The government grew very concerned, and in 1986 Congress passed the National Childhood Vaccine Injury Act (NCVIA). The act established a new system for vaccine-related injuries or death linked to childhood vaccinations, wherein companies were indemnified from being sued for safety problems. (Soon after, the program was enlarged to include adult vaccination injuries.) If anyone believed that a child or person was injured by a vaccine, they could take the complaint to a newly established vaccine court, run by the U.S. government, and plead their case. If they won, the government would pay them damages from a fund it created out of taxpayer money.

This might have seemed the best possible solution: The country retained a vaccine supply, and citizens had recourse in the event of harm. But because companies were indemnified from any harm their vaccines might cause, they no longer had a powerful financial incentive to rectify existing safety problems, or even improve safety as time passed. Arguably, they were financially disincentivized from doing so. The solution shifted liability for the costs of safety problems from the makers onto the taxpayers, the pool that included those who were arguably harmed.

This atmosphere of suspicion spread in the 1990s, with even greater explosiveness and toxicity, during the vaccine autism debate. The landscape of the vaccine discourse in the United States—never simple or one-dimensional to begin with—was becoming even more complicated and hostile.

To understand the polarized psychological reactions to vaccination now, as well as what to do about it, it is essential to disentangle three things:

First, there is the kernel idea behind vaccination as a treatment, arguably one of humanity’s greatest medical insights.

Second, there is the process by which a particular vaccine is produced, tested for safety and efficacy, and regulated—i.e., the execution of the core insight, which, as we know, can vary in success from one vaccine to the next, or fail completely. (We’ve not yet been able to make an AIDS vaccine, for instance.)

Third, there is the way in which those who produce the vaccine, and the public health officials in charge of regulating and disseminating it, communicate to the public.

Only a person who rejects that first kernel idea could sensibly be called an “anti-vaxxer.” Many people accept the kernel insight and have been vaccinated multiple times in the past, but have come to doubt the execution or necessity of a particular vaccine, and hence also come to doubt the claims made in the course of disseminating it. They become hesitant about that particular vaccine, and defer or avoid getting it.

One reason hesitancy can take hold in relatively low-trust societies is that reluctant vaccinees typically have no direct relationship with those mandating vaccinations, and thus no personal evidence that those people are trustworthy. For a regular medication, a physician needs and has the ability to convince one patient at a time to take a particular drug. This is why pharmaceutical companies have huge marketing budgets to sway individual physicians and patients alike. In the case of vaccines, companies need to convince only a few key officials and committees, who then buy their product and market it for them to an entire population. For companies producing vaccines, mass marketing is replaced almost entirely by political lobbying.

A number of events occurred in the 1990s that suggested the growing enmeshment between the pharmaceutical industry and scientists involved in drug production and approval decisions—along with the role of profit in the whole arrangement—was becoming an endemic problem. In 2005 the Associated Press reported that “two of the U.S. government’s premier infectious disease researchers are collecting royalties on an AIDS treatment they’re testing on patients using taxpayer money. But patients weren’t told on their consent forms about the financial connection.” One of them was helping to develop an interleukin-2 treatment, tested around the globe. The problem, as those reports noted, was that “hundreds, perhaps thousands, of patients in NIH experiments made decisions to participate in experiments that often carry risks without full knowledge about the researchers’ financial interests.”

Vaccines are a one-size-fits-all intervention—administered en masse.

One of the two people running these experiments was a researcher named Dr. Anthony Fauci, who first rose to prominence a decade before in the AIDS crisis. Not only was the assertion about royalties true; it was also perfectly legal. Royalties for public service scientists were first allowed under the Bayh-Dole Act of 1980, which had attempted to remedy two related problems: the lack of reimbursement for government-funded research, and retaining top scientists who were being lured away from public work by the private sector. This act and other federal regulations permitted the NIH, for instance, to collect proceeds if its research made money in the private sector, and allowed individual government scientists to collect up to $150,000 a year in royalties on treatments they developed.

At the time, Fauci said he tried to alert patients to his royalties, but his agency rebuffed him, arguing that he couldn’t do so under the law. The nondisclosure of the researcher’s interest was changed after the scandal, but damage had been done. In the minds of some elements of the public, there was something fishy going on between the government and the pharmaceutical industry—and it had something to do with money and a willingness to disregard or dilute informed consent.

These suspicions heightened in the 2000s, as key physicians began revealing to the public that Big Pharma had been involved in a number of major abuses of its relationships with government, patients, physicians, and journals. One of the first to break this story was Marcia Angell, who had been editor of the New England Journal of Medicine, arguably the most important medical journal in the United States at the time. In her 2004 book, The Truth About the Drug Companies: How They Deceive Us and What to Do About It, she argued that the companies spent far more on marketing, administration, public relations, and rebranding than they did on research, and that they actually discovered very few new effective drugs. Instead, they used “lures, bribes, and kickbacks,” to get drugs taken up by physicians. Angell showed how these companies penetrated medical schools, conventions, and organizations, often passing off marketing as “education,” which they provided free of charge.

More to the point, Angell argued that government agencies were highly compromised. She demonstrated how conflicts of interest permeated the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, which gave “expedited” reviews and approvals for drugs with major side effects like heart attacks and stroke (such as Vioxx and Celebrex), and some with no serious benefit. Angell also revealed that “many members of the FDA advisory committees were paid consultants for drug companies. Although they were supposed to excuse themselves from decisions when they have a financial connection with the company that makes the drug in question, that rule is regularly waived.” She documented multiple instances of committee members discussing decisions on safety violations committed by the very companies that paid them, from which they did not recuse themselves.

Angell’s book, which was published to great acclaim, was impossible to dismiss as fringe. “Dr. Angell’s case is tough, persuasive, and troubling,” claimed The New York Times. Publisher’s Weekly wrote: “In what should serve as the Fast Food Nation of the drug industry, Angell … presents a searing indictment of ‘big pharma’ as corrupt and corrupting.” Over the next few years, the kinds of abuses she documented made it to the courts. As these trials became public, Americans who suffered from serious side effects caused by the drugs involved took notice.

In 2012, physician Ben Goldacre of Oxford University published Bad Pharma, in which he explored fraud settlements for pharmaceutical companies covering up known adverse events, including lethal ones, and hiding information, including about safety. The book’s subtitle—How Drug Companies Mislead Doctors and Harm Patients—was key: Physicians often didn’t know the wool was being pulled over their eyes, or what had been kept from them. But when the practices of large pharmaceutical companies were examined in the courts, with internal documents reviewed, one illegal activity after another was revealed. Goldacre’s list makes one shudder:

“Pfizer was fined $2.3 billion for promoting the painkiller Bextra, later taken off the market over safety concerns, at dangerously high doses (misbranding it with ‘the intent to defraud or mislead’) … the largest criminal fine ever imposed in the US, until it was beaten by GSK [GlaxoSmithKline].” [...]

“In July 2012, GSK received a $3 billion fine for civil and criminal fraud, after pleading guilty to a vast range of charges around unlawful promotion of prescription drugs, and failure to report safety data.” [...]

“Abbot was fined $1.5 billion in May 2012, over the illegal promotion of Depakote.” [...]

“Eli Lilly was fined $1.4 billion in 2009.” [...]

“AstraZeneca was fined $520 million in 2010.” [...]

“Merck was fined $1 billion in 2011.”

After Goldacre’s book was published, the fines kept coming. Johnson & Johnson was made to pay $2.2 billion in 2013, which included, according to the Justice Department, “criminal fines” for having “jeopardized the health and safety of patients and damaged the public trust”; in 2019, the company was fined another $572 million for its role in the opioid epidemic, and then fined a whopping $8 billion by a jury in a different case—an amount that will no doubt be reduced, but which signals public outrage at the violations.

These huge fines, year after year, involve popular drugs taken by tens of millions of patients, with negative effects—including death. Stories of devastation have become lore in many families and communities. The circle of concern is even wider if you include those who may not have been personally affected, but are aware of this problematic legal history. When you personally take a medication, you tend to notice news about it, especially bad news. Whether or not you’ve experienced any negative effects yourself, you are naturally alert to their existence. Each time a Big Pharma company is in the courts and in the media because of some problem, the seeds of skepticism are planted in the minds of many Americans.

And not just skepticism of the companies themselves. The transgressions mentioned above were only possible on such a scale because of a textbook case of regulatory capture, consisting of a mixture of perverse incentives and priorities, a tolerance for nontransparency, and, in some cases, a culture of collusion. The FDA bills Big Pharma $800 million a year, which in turn helps pay FDA salaries. Regulators also often get jobs in the pharmaceutical industry shortly after leaving the FDA or similar bodies; there is a huge incentive to impress, and certainly not to cross, a potential future employer.

It’s useful to see how this works by examining a case that became famous as a tale of epic greed and corruption, and in which patients and physicians were misled and deceived, only after patients, families, activists, and even whole communities yelled themselves hoarse about it for years.

In 1995, the FDA approved Oxycontin for short-term serious pain, like terminal cancer or postoperative pain. This approval was based on legitimate scientific studies related to these narrow experiences. The FDA then made it available for minor pains, with around-the-clock daily usage, in 2001. That approval (for long-term use) was not based on any studies. According to a 60 Minutes report in 2019: “Equally suspicious but legal [was] the large number of key FDA regulators who went through the revolving door to jobs with drug manufacturers.”

The opioid epidemic has, to date, left half a million Americans dead.

This same compromised regulatory system allows Big Pharma to pay for, and play a key role in performing, the very studies that lead to the authorization of its own products. For decades, it was not just common for authors of studies to receive payments from the very companies making the medicines being tested; it was also systematically hidden. Drug companies secretly ghostwrote studies of their own drugs; Goldacre shows how they conscripted academics to pretend they had authored them. The papers were then submitted to mainstream journals, whose imprimatur would give the studies credibility, allowing these drugs to become the “standard of practice.”

Sixteen of the 20 papers reporting on the clinical trials conducted on Vioxx—the anti-inflammatory and pain medication that got FDA approval in 1999, then was taken off the market in 2004 for causing heart attacks and strokes—were ghostwritten by Merck employees, then signed by respected scientists. Merck ultimately agreed to pay out $4.9 billion in Vioxx lawsuits. The academics who lent their names to the studies could then stuff their CVs with these articles, receive promotions and higher salaries within academia, and ultimately get more consulting fees from pharmaceutical companies, at which point they are seen as “experts” by a trusting public.

In the current regulatory environment, companies run the studies of their own products. A Danish study found that 75% of drug company self-studies assessed were ghostwritten. A leading U.S. editor of a specialist journal estimated that 33% of articles submitted to his journal were ghostwritten by drug companies. These impostures don’t get adequately investigated by Congress because the pharmaceutical and health industries are now the highest-paying lobby in the country, having doled out at least $4.5 billion in the last two decades to politicians of both parties. “Pfizer’s PAC has been the most active,” STAT reporter Lev Facher writes, “sending 548 checks to various lawmakers and other industry groups—more checks than the actual number of elected officials in the House and Senate.”

While Goldacre’s book shows the many ways that drug studies have been rigged to deliver certain outcomes, one doesn’t always have to rig a study to get the same result. Among the most common techniques is to delay the reporting of medication side effects until after the patent runs out—and then use the bad publicity to sell a new replacement medication, which is still on patent.

Polls repeatedly show that the chief concern among the vaccine hesitant is about side effects, or at least effects that don’t show up right away. The latest edition of the standard textbook in the field, Plotkin’s Vaccines, has an excellent chapter on vaccine safety, which notes: “Because reactions that are rare, delayed, or which occur in only certain subpopulations may not be detected before vaccines are licensed, postlicensure evaluation of vaccine safety is critical.” Postlicensure first requires FDA approval, so for most vaccines that means more follow-up after the typical two-year approval process—at least several years of it.

In 2018, The New York Times’ pro-vaccine science writer, Melinda Wenner Moyer, noted with shock that she learned it was not uncommon among vaccine researchers to take the attitude that censoring bad news about their research was necessary, and that some who didn’t were ostracized by their peers:

As a science journalist, I’ve written several articles to quell vaccine angst and encourage immunization. But lately, I’ve noticed that the cloud of fear surrounding vaccines is having another nefarious effect: It is eroding the integrity of vaccine science. In February I was awarded a fellowship by the nonpartisan Alicia Patterson Foundation to report on vaccines. Soon after, I found myself hitting a wall. When I tried to report on unexpected or controversial aspects of vaccine efficacy or safety, scientists often didn’t want to talk with me. When I did get them on the phone, a worrying theme emerged: Scientists are so terrified of the public’s vaccine hesitancy that they are censoring themselves, playing down undesirable findings and perhaps even avoiding undertaking studies that could show unwanted effects. Those who break these unwritten rules are criticized.

Moyer went on to quote authorities who argue that smaller studies, and even inconclusive ones, often give us the first glimpse of an insight or problem. And this is to say nothing of the wider issue: If scientists play down their undesirable findings in potentially mandated medicines, as Moyer found them to be doing, they are not just missing opportunities for good science; they are potentially generating anti-scientific misinformation. “Vaccine scientists will earn a lot more public trust, and overcome a lot more unfounded fear, if they choose transparency over censorship,” she wrote.

By the time Moyer published her article in 2018, many Americans were already long in the habit of questioning certain elements of their public health, in part because of this hornet’s nest of corruption and regulatory capture. But this habit could also be explained in part by the general trend in medicine over the past two decades toward recognizing the superiority of individually tailored interventions, or personalized medicine, which acknowledges that different people have different risk factors, genetics, medical histories, and reactions to medical products. It is now commonplace for people to take responsibility for their own health because this is precisely what we have been telling them to do—encouraging them to get to know their own unique risk factors for disease, based on their own individual histories and genetics.

Vaccines, in contrast, are a one-size-fits-all intervention—administered en masse by those who know nothing specific about vaccinees or their children. When political and medical authorities change policies from day to day, and public health recommendations in one jurisdiction or country differ from those in others, questions will be asked. The public has been assured that we in health care recognize that the era of medical authoritarianism, and the ugly practices that led us to require informed consent, are behind us. This means that whenever there is a treatment on hand, the burden of proof to demonstrate that it is safe and effective must fall on those who offer it. It means we must never stifle questions, or shame people for being anxious.

I am a psychiatrist and a psychoanalyst, and I deal with people’s anxieties—and their paranoia too. Many people think “the anxious” are necessarily weak (one medical colleague calls the vaccine hesitant “wimps”). But this is, if not entirely wrong, a superficial way of understanding anxiety. Anxiety is a signal. It evolved to get us to pay attention to something—sometimes an external threat, and sometimes an internal one, such as an ignored feeling or forbidden thought threatening to emerge from within. Anxiety can be neurotic. It can even be psychotic. It can also save your life, because dangers do exist. When people don’t experience enough anxiety, we say they’re “in denial.”

Thus, in some situations, the capacity to feel anxiety can be an advantage, which is likely why it is preserved in evolution in so many animals. Aristotle understood this very point long ago; as he noted, the courageous person, say a soldier, can and should feel anxious—he is facing a danger, after all, and his wisdom tells him there is risk. What distinguishes the courageous person from the coward is not that they don’t worry or fear, but that they can still manage to move forward into the dangerous situation they cannot avoid facing. All of which is to say that the presence of anxiety alone is not dispositive of sanity or insanity: It, alone, does not tell you whether the anxiety is well or ill-founded. The same goes with distrust. Sometimes distrust is paranoia, and sometimes it is healthy skepticism.

As of a September 2019 Gallup poll, only a few months before the COVID-19 pandemic, Big Pharma was the least trusted of America’s 25 top industry sectors, No. 25 of 25. In the eyes of ordinary Americans, it had both the highest negatives and the lowest positives of all industries. At No. 24 was the federal government, and at No. 23 was the health care industry.

These three industries form a neat troika (though at No. 22 was the advertising and public relations industry, which facilitates the work of the other three.) Those inside the troika often characterize the vaccine hesitant as broadly fringe and paranoid. But there are plenty of industries and sectors that Americans do trust. Of the top 25 U.S. industry sectors, 21 enjoy net positive views from American voters. Only pharma, government, health care, and PR are seen as net negative: precisely the sectors involved in the rollout of the COVID vaccines. This set the conditions, in a way, for a perfect storm.

Continue to Chapter III. Or return to Chapter I. To download a free, printer-friendly version of the complete article, click here.

Norman Doidge, a contributing writer for Tablet, is a psychiatrist, psychoanalyst, and author of The Brain That Changes Itself and The Brain’s Way of Healing.