Can Agnon’s Goat Speak English?

Reading the great Hebrew writer in Toby Press’ translation to English, 50 years after his Nobel prize, brings his layered simplicity to a new and deserving audience

My first encounter with the work of S.Y. Agnon, the only Hebrew-language writer to win the Nobel Prize for Literature, was at age 16, in Hebrew. I was an American public-school kid studying Hebrew in a JCC adult ed. class, in which I was the only student who wasn’t retired. Hebrew intimidated me then; no matter how many verbs I mastered, there was an invisible wall of Israeliness between me and the articles about political parties and terrorist attacks that we haltingly translated from the newspaper Ma’ariv. The Hebrew I knew from my own life—from the synagogue where I had become a weekly Torah reader at 12, or from my home where my mother’s artwork was infused with calligraphic Hebrew phrases from the liturgy—seemed to be something totally unrelated to “Hebrew.” Until I read Agnon’s “Fable of the Goat.”

Here, to my astonishment, I knew all the main characters intimately: the father who spoke in words I recognized from Jacob in Genesis; the son who searched for a lost animal in phrases I remembered from Song of Songs. And here, too, was the character I knew best from the most tedious weekly Torah readings: the goat. Doomed to either sacrifice or wandering, the enabler of every speck of spiritual meaning and yet no more than an instrument of the divine will, this goat appeared in everything from the Torah to Had Gadya to this story before me, a comically wacky symbol of this weirdly eternal people to whom logic never seemed to apply.

What Agnon did with these familiar characters was so seemingly simple that it couldn’t but mean absolutely everything. Riffing on so many biblical and rabbinic themes that one could barely track them all, the story begins with a sick man whose doctors prescribe goat’s milk. But the goat he buys periodically wanders off for days, returning with udders full of milk whose taste is “like a taste of the Garden of Eden.” The man’s son decides to tie a cord to the goat’s tail and follow her. The goat then leads the son into a cave, an underground tunnel to an almost-mythical Land of Israel. (Rabbinic tradition suggests that when the messiah arrives, the diaspora Jewish dead will travel from their graves to Israel through underground caverns.) In the mystical city of Safed, the excited son is about to go back and get his father when he realizes that the Sabbath is approaching and he cannot travel. He quickly writes a note to his father to follow this goat, sticks the note in the goat’s ear, and sends her back through the tunnel. But when the goat arrives, the father assumes his son his dead; he has the goat slaughtered, and only then discovers the note. The father laments how he has doomed himself to exile, while the son flourishes “in the land of the living.”

The many dimensions of this story were apparent to me even at 16, particularly its anti-religious undercurrent (the Sabbath ruins everything!). But the story’s power was much more intimate than that. The tunnel between the diaspora and Israel felt to me exactly like the language into which I was entering: a language which took me both into and out of my own life, on a hidden route that required ever-deeper digging into layers of the past. For the first time in Hebrew, I felt at home in my native discomfort.

***

All great writers are to some extent untranslatable. But the liabilities of translation are usually limited to the lack of equivalents for a writer’s specific wordplay or tone. Translating Agnon involves much more. Nearly every word is an allusion to thousands of years of words. A typical Agnon story or novel is like a tel, an archaeological mound composed of the remnants of past civilizations, each layer destroyed and rediscovered and given new, often ironic significance. As if that weren’t enough, the stories themselves often have layers within Agnon’s own imagined world, because he often rewrote his stories in different published versions with entirely different meanings. Consider, for instance, his story “Tale of the Scribe,” which Agnon dedicated to his wife. It’s a bizarre faux-pious tale about a scribe whose beloved wife (who is “barren”… possibly because they have never had sex?) drops dead; when he writes a Torah in her memory, his final dance with the scroll is a kind of dance with her ghost. The story is romantic and anti-romantic, religious and anti-religious, and above all, haunting. But it’s also part of a constellation of other Agnon stories about this same scribe, including an early Yiddish story called “Toytntants” (“Dance of Death”) about a secular writer mourning a lost lover, who writes a story dedicated to his beloved—a story about a scribe whose beloved wife dies and in whose memory he writes a Torah scroll. (Are you still with me?) This is only one of at least four Agnon stories involving some version of these characters that I have personally managed to track. It’s very possible there are others I have missed.

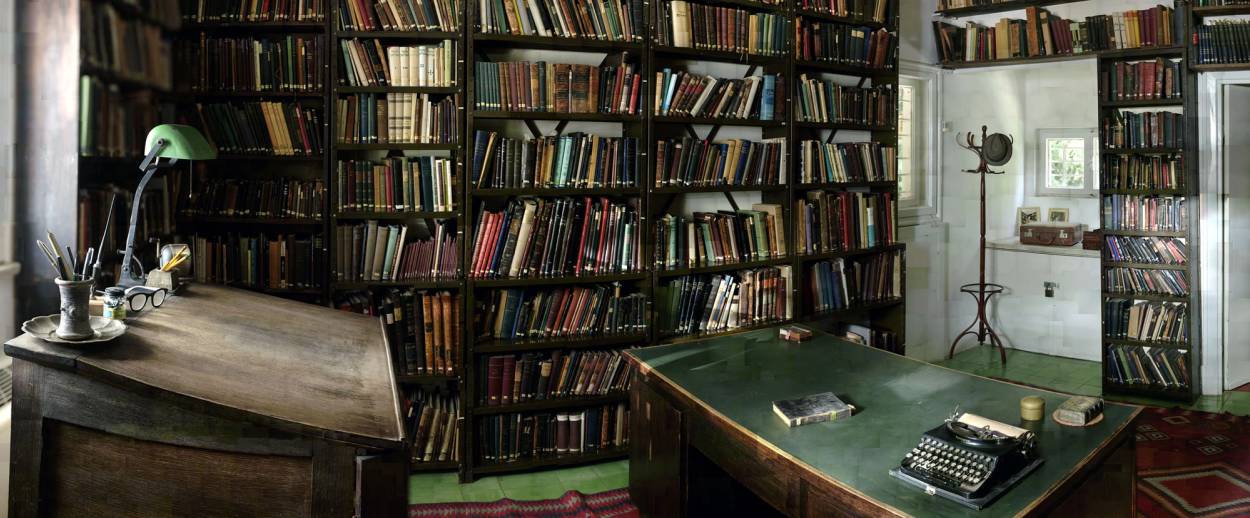

This doesn’t even begin to describe the meta-fictional Agnon universe, which includes Agnon himself. It probably goes without saying that Agnon is not his real name. In a meta-fictional coup that gleefully borrows from traditional Jewish literature (in which many rabbinic figures are known by the names of their books), the author Shmuel Yosef Czaczkes named himself after one of his stories: “Agunot” (literally “chained women;” a legal term for abandoned wives who cannot remarry), about star-crossed lovers/artists whose doomed destinies span Israel and the diaspora. But the pen name is the tip of the iceberg. Agnon moved from Poland to Ottoman Palestine in 1908 and thereafter cast himself as a “Land of Israel” man—but four years later he returned to Europe, settling in Berlin, where stayed until 1924 when his house burned down in a fire that destroyed his library of 4,000 Hebrew books and also 700 pages of the novel he was writing, titled Eternal Life. (Don’t get me started on the Jewish symbolism of burnt houses and lost books, least of all lost books called Eternal Life.) After this First Temple was destroyed, Agnon returned to the Holy Land, where his Second Temple—his house near Jerusalem—was also destroyed, this time by Arab rioters in 1929. These things really happened, but in his fiction Agnon transformed these events into cornerstones of legend, creating a literary world that turned private experience into a kind of Jewish collective unconscious.

Agnon’s self-mythologizing even included his birth date. He claimed he was born on the ninth of the Hebrew month of Av—the date on which the First and Second Temples were destroyed, and according to rabbinic legend, also the date on which the Messiah will be born. Claiming birth on the ninth of Av is therefore either a fun fact, a pious expression of immense hubris, or a hilarious deadpan joke—and the same can be said of pretty much every line Agnon ever wrote. Once he won the Nobel and started fielding interviews from non-Jewish outlets, he began claiming that he’d been born on the portentous, if less momentous, date of 8/8/1888. It probably also goes without saying that 8/8/1888 did not fall anywhere near the ninth of Av.

This kind of ironic play with Jewish and non-Jewish sources isn’t just a major element of Agnon’s fiction. To a large extent, it is his fiction. But is there any way for non-Hebrew readers to appreciate it? As the astonishing translated collection of Agnon’s works recently released by the heroic Toby Press demonstrates, the answer is yes.

Reading through this vast and magnificent collection of works, including many newly translated into English, I discovered that the Agnon one experiences in translation—even excellent translations, as these uniformly are—is undeniably a different Agnon than one experiences in Hebrew. Not, thankfully, a worse Agnon, but one with manifestly different strengths. For instance, in Hebrew one is constantly aware of Agnon’s identity as a “Land of Israel” writer. His Hebrew reputation is staked almost entirely on creatively reviving ancient elements of the Hebrew language and its Israel-based roots; the fact that the bulk of his work is actually set in Europe seems, at times, almost like a detail. But in translation, without Hebrew’s undertow back to the land of its origin, it becomes blindingly obvious that Agnon is in fact one of the greatest artists of the lost world of Eastern European Jewry.

When one reads through these works in English, the center of Agnon’s imagination no longer seems to be Jerusalem but rather “Szybusz” (literally “a muddle”), Agnon’s stand-in for his actual Polish hometown of Buczacz. While Agnon’s Israel-based stories sometimes feature recurring characters, the Szybusz stories feature an entire recurring city, with minor figures from one tale appearing as protagonists in others, still living at the same address where they lived in the last book. This recurring cast is unforgettable. The wounded war veterans, the Zionists, the Communists, the Socialists, the traditional parents and their unsatisfied children, the scholars whose ego battles are parodies of scholarship, the train trips to bumpkin relatives or sanatoriums in other towns, the class hierarchies between starving scholars, domestic servants, bourgeois shopkeepers, and those who (apparently) have it made by working for non-Jewish bigwigs—these people and the everyday European realities move in and out of these stories with a fundamental realness that belies all the meta-fictional games Agnon loved to play. These characters are invariably stuck, whether in loveless marriages or pointless study sessions or failing businesses or even the logistics of modern life; one newly translated novel, To This Day, set in Germany during the first World War, has a protagonist whose life is comically defined by constantly getting evicted from boarding houses and always missing the next train. Some of these works were written before the Holocaust and some after, but they all exist in a state of agunah-like suspension, evoking a world haunted by unfulfilled potential.

Agnon’s characteristic dreamlike suspension between possibilities will feel familiar to anyone living a Jewish life in the diaspora, even in translation. But reading these works in translation is also an act of mourning: not only for the world Agnon resurrects, but also for that well of allusions that English readers cannot hear. Every moment of bumping up against one of those Christian-sounding translated biblical phrases contains a jarring reminder of something inaccessible.

Yet there is one new work that gave me an absolutely radical hope for a new audience for Agnon: a picture-book volume whose untranslatable Hebrew title, “Shai ve-Agnon” (a pun on the author’s and illustrator’s names) has been rendered in English as “From Foe to Friend.” Billed somewhat misleadingly as a “graphic novel,” this brilliant work is a comic-book version of three of Agnon’s stories, illustrated—though the verb hardly does the work justice—by the renowned Israeli cartoonist Shai Charka. As Charka himself puts it, “When I read Agnon’s stories I see entire worlds ‘drawn’ in my imagination. Worlds which contain images not described in Agnon’s own words, but which unravel the riddles of his stories. … I saw all these things and wanted to share them with you—so I drew them.” I would never have dreamed that any derivative work could add depth to the bottomlessness that is Agnon, much less a picture book clearly intended for children. But dear reader, it has happened. And it is miraculous.

All three stories in “From Foe to Friend” are astonishing, even the mythological-autobiographical title piece about how Agnon built his house in Talpiot—which at first appears to be nothing more than a rewriting of “The Three Little Pigs” but which, once you remember you are reading Agnon, is a gut-wrenching commentary on what it really meant to settle in pre-state Israel. (It includes a sickening passing reference to the Arab rioters who destroyed Agnon’s home.) There is sheer delight and amazement in the story “The Architect and the Emperor,” drawn from the novel To This Day, which in the original feels like a defeatist Kafkaesque fable, but here becomes a paradigm-shifting interpretation of Zionism itself. But the one that moved me most was “Fable of the Goat.”

I had not read “Fable of the Goat” in more than 20 years. Yet here it is, alive on the page in ways I could never have imagined would be so powerful and moving. The cartoon format seems at first to belittle the story; I was dismayed to see the story’s shtetl portrayed with an actual fiddler on a roof. But then the goat appears, and something new arrives in the story that wasn’t there in the original. The goat is an actual character, not a delivery device for a message but a being with emotional depth, a character full of milk and also full of joy, hesitation, anxiety, and terror.

In Agnon’s story, the goat’s journey through the cave is dispensed with in a few lines. But this is where Charka does something so breathtaking that I almost thought I dreamed it. When Charka’s goat enters the cave, she quickly finds herself on the edge of a precipice—where she is pushed over the edge by a faint outline of a man in the garb of the high priest. This, as Torah readers like me know, is the biblical scapegoat, the one on whom the high priest confesses the sins of the people and who is then taken to the wilderness and pushed off a cliff. Dayenu. But then the journey continues. On the next page, we see the goat trotting past an altar with a bound figure on it, a hand with a knife hovering above, alongside a ram caught in a thicket of thorns: the binding of Isaac, the first of the Torah’s covenantal contradictions. The goat then slinks along a wall with drawings of a goat being beaten by an Egyptian taskmaster, then being borne on a man’s back to another part of the page. There, a Pan-like satyr pursues the goat around a Greco-Roman column, toward wall drawings borrowed from the 14th century “Bird’s Head Haggadah” depicting Jews in hats they were forced to wear in parts of medieval Europe. Here the goat is chased by a cat who is chased by a dog who is chased by a stick …which is burnt by a fire on a torch held by a Grand Inquisitor figure, who singes the goat’s tail while prodding her toward a bonfire for an auto-da-fe. On the following page, marching scissors wearing World War I helmets cut off the goat’s beard, and then disembodied butcher’s knives lop off the goat’s horn—which becomes a shofar, which blasts the goat and the boy out of the cave and into the Land of Israel.

All of this is the opposite of subtle, a cartoon version of Jewish history. It’s all over in two pages. Yet even though I have probably read hundreds of books on Jewish history, never before have I understood the raw emotional horror and power of that journey as instantaneously I did from glancing at those two pages with that little goat.

This is precisely the effect of reading Agnon in Hebrew: the illusion of simplicity and the symbols that refuse to remain symbolic, all layered over a deep emotional burrowing through time and pain and renewal, until the reader has the sudden feeling that the essence of existence is right here, in this story. Fifty years after Agnon received the Nobel Prize, it’s a relief and a joy to know that for English readers, that tunnel between reality and dream is now open.

***

To read a new translation of ‘Rothschild’s Luck; or, A Tale of Two Patrons,’ by S.Y. Agnon, in Tablet magazine, click here.

Dara Horn is the award-winning author of five novels and the essay collection People Love Dead Jews.