When Feminists Were Zionists

A new generation of women is being misled into assuming an ideological tension between feminism and Zionism

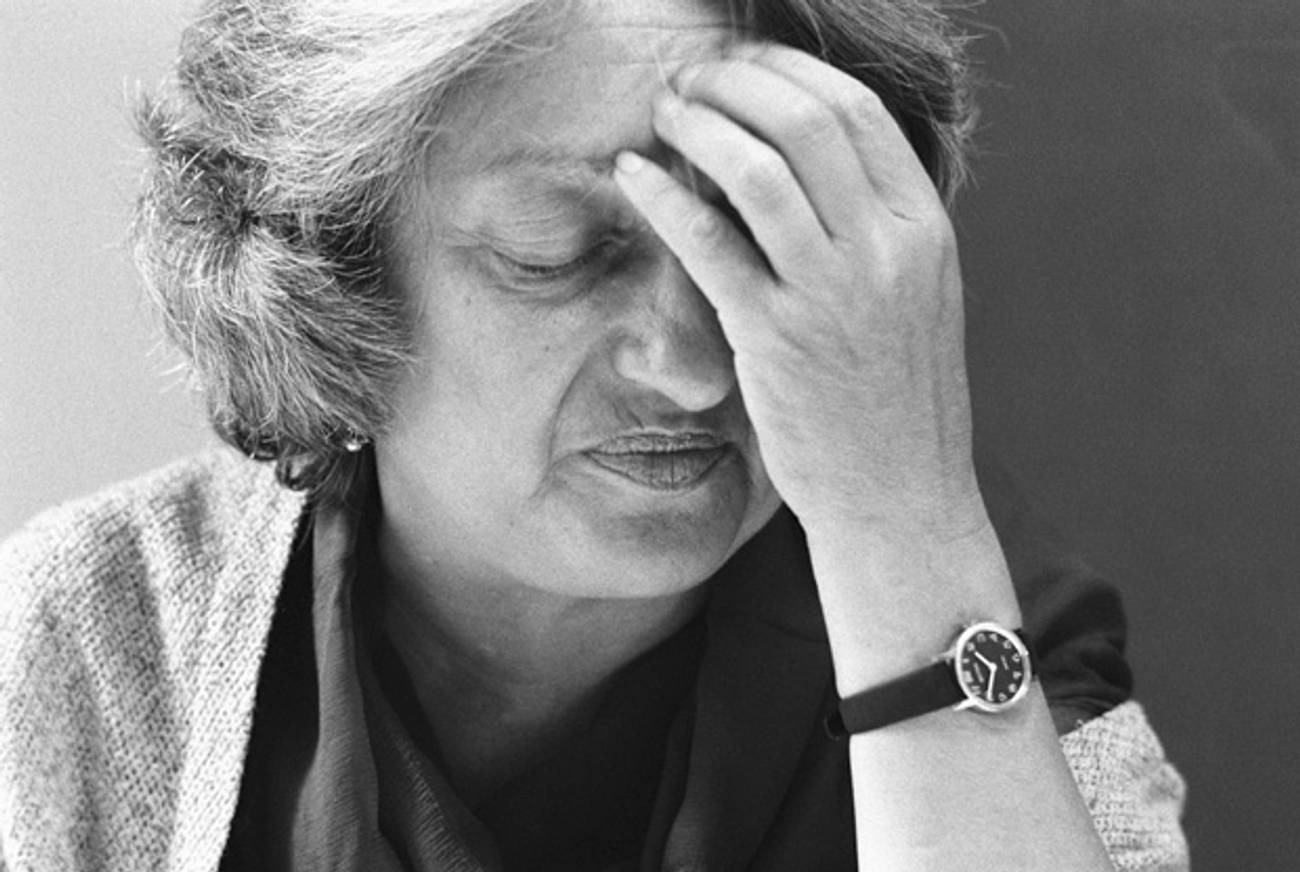

In June 1975, weeks after Saigon fell, Betty Friedan led a large delegation of American feminists to Mexico City for an International Woman’s Year World Conference hosted by the United Nations. The feminist trailblazer—whose legacy is in the spotlight on International Women’s Day today, 50 years after the publication of her book The Feminine Mystique—traveled south “relatively naïve,” she would recall, hoping “to help advance the worldwide movement of women to equality.” Instead, she endured what she called “one of the most painful experiences in my life.”

The conference’s anti-Americanism, anti-Semitism, and anti-Zionism shocked Freidan—and diverted attention from the feminist agenda. Men, political spouses, or “female flunkies,” she noted, dominated most official delegations. Few of the delegates seemed interested in women’s issues. American feminists were mocked as spoiled bourgeois elites raising marginal concerns to avoid confronting more pressing issues of racism, imperialism, colonialism, and poverty. A thuggish atmosphere intimidated the American feminists, especially in the parallel NGO, or non-governmental organization, conference. At critical moments “microphones were turned off” and speakers shouted down. Friedan recalled in notes found in her papers, which formed the basis of her famous article “Scary Doings in Mexico City”: “the way they were making it impossible for women to speak—on the most innocent, straightforward of women’s concerns, seemed fascist—like to me, the menace of the goosestep.” Friedan saw the Israeli prime minister’s wife, Leah Rabin, booed and boycotted, and she watched, horrified, as the “Declaration on the Equality of Women” became one of the first international documents to label Zionism as a form of racism.

When Third World and Communist delegates moved to link the Ten-Year Plan of Action for Women to the abolition of “imperialism, neocolonialism, racism, apartheid, and Zionism,” some feminist voices finally broke the silence. One European woman delegate told Friedan: “That is clear anti-Semitism, and we will have no part of it.” “If Zionism is to be included in the final declaration, we cannot understand why sexism was not included,” T.W.M. Tirika-tene-Sullivan, heading the New Zealand delegation, shouted. Lacking a two-thirds majority, the Arab and Communist delegates forced through a procedural change requiring only a majority vote to approve a declaration so that the anti-Zionist plank could pass.

Under attack, “followed by gunmen and advised to get out of town,” and ultimately hustled out of the hall by three large women from Detroit who were concerned about her physical safety, Friedan had her consciousness raised in a new way. She had been criticizing American society for years. Regarding Judaism and Israel, she had been ambivalent, saying her “own background was not that religious.”

Following the conference, Friedan viewed these democracies’ flaws in perspective. America was at least acknowledging sexism as a problem. Upon her return to the United States, she also dedicated herself to the Zionist cause, advocating Jewish self-defense in confronting vicious, obsessive lies about Israel.

The Mexico City experience integrated Friedan’s two embattled identities. She later celebrated the “new strength and authenticity of women as Jews, and Jews as women, which feminism has brought that enables them to combat the use of feminism itself as an anti-Semitic political tool.” She linked this struggle to “part of the larger never-ending battle for human freedom and evolution. Women as Jews, Jews as women, have learned in their gut, ‘if I am not for myself, who will be for me (and who can I truly be for). If I am only for myself, who am I?’ ”

Back home in New York, when the United Nations considered expelling Israel that fall of 1975, Friedan mobilized against the move in order, as she put it, to “save the U.N.” She noted that, having risen from the “ashes of the Holocaust,” the United Nations was now sacrificing its credibility in targeting one country. Many of the Asian and African delegates agreed with Friedan and vetoed the move, unwilling to risk their new status as member states by questioning Israel’s right to belong.

The Soviets and the Palestinians then turned to their fallback position: having the General Assembly label Zionism racism. The Soviets hoped to humiliate the United States, six months after South Vietnam fell. And beyond their terror attacks and diplomatic grandstands, the Palestinians were fighting an ideological war. They framed their local narrative, Edward Said explained, as part of “the universal political struggle against colonialism and imperialism.”

Proclaiming that “all human rights are indivisible,” Friedan’s Ad Hoc Committee of Women for Human Rights objected to the racist label being “applied solely to the national self-determination of the Jewish people.” Politicians including Bella Abzug, Helen Gahagan Douglas, Margaret Heckler, Elizabeth Holzman, and Pat Schroeder; celebrities including Lauren Bacall, Beverly Sills, and Joanne Woodward; writers including Nora Ephron, Margaret Mead, Adrienne Rich, and Barbara Tuchman; Joan Ganz Cooney of Sesame Street; La Donna Harris, the American Indian activist; and the feminist Gloria Steinem, among others, joined Friedan’s committee.

Despite Friedan’s efforts, and despite the eloquence of U.N. Ambassador Daniel Patrick Moynihan’s opposition to “this infamous act,” General Assembly Resolution 3379, which labeled Zionism as a form of racism, passed on Nov. 10, 1975. The next day, Friedan made a surprise appearance at an anti-3379 protest, where she identified herself “as a woman, as an American, and as a Jew.” She proclaimed: “All my life I have fought for justice, but I have never been a Zionist until today.”

Subsequently in an American Jewish Congress Symposium called “Woman as Jew, Jew as Woman,” Friedan would root her feminism in her Judaism. She often wondered, “Why me?”—what prompted her to confront sexism? Eventually, she traced “this passion against injustice” to the values she absorbed and the mild anti-Semitism she experienced “as a Jew growing up in Peoria, Illinois.”

Friedan’s Jewish transformation was mostly public and political. Letty Cottin Pogrebin experienced a more personal awakening. Pogrebin wrote in her 1991 memoir, Deborah, Golda and Me, that although Israelis were targeted, “I knew the arrow also was meant for me.”

She realized that “to feminists who hate Israel, I was not a woman, I was a Jewish woman.” Launching a deeper Jewish journey, Pogrebin wondered: “Why be a Jew for them if I am not a Jew for myself?” Many Jews reported experiencing an identity reawakening following the public trauma of the “Zionism is racism” resolution. Like Pogrebin, and Theodor Herzl, many discovered that anti-Semitism can make the Jew, but it is more satisfying for the Jew to make the Jew.

Yet many feminists, Jewish and not, felt that solidarity with international women’s conferences was more important to the movement than the fate of the Jews. Pogrebin confronted feminist anti-Zionism in her controversial June 1982 Ms. Magazine article “Anti-Semitism in the Women’s Movement.” There Pogebrin defended Zionism as an experiment in realistic nationalism. “If we can understand why history entitles lesbians to separatism, or minorities and women to affirmative action, we can understand why history entitles Jews to ‘preferential’ safe space,” she wrote. “To me, Zionism is simply an affirmative action plan on a national scale. Just as legal remedies are justified in reparation for racism and sexism, the Law of Return to Israel is justified, if not by Jewish religious and ethnic claims, then by the intransigence of worldwide anti-Semitism.” Pogrebin echoed the radical thinker Andrea Dworkin’s vision: “In the world I’m working for, nation states will not exist. But in the world I live in, I want there to be an Israel.”

Globally, the battle only got nastier, and weirder. U.N. organizations and conferences worked diplomatically to “add Zionism to all the nasty ‘isms’ ” the world wanted “eliminated,” lamented the Israeli diplomat Tamar Eshel, who represented Israel at the U.N.’s International Women’s Conference in Copenhagen in July 1980. A huge portrait of Ayatollah Khomeini, Iran’s Islamist anti-feminist leader, decorated the conference headquarters, inside of which attacks on Israel, Jews, and America intensified. Most Third World delegates decided sexism was a Western problem, because only Western women complained about it.

Co-chairing the American delegation was Sarah Weddington, a special assistant to President Jimmy Carter, and the winning lawyer in the Supreme Court abortion case Roe v. Wade. Disgusted by what she saw unfolding in front of her, she had her own Moynihan moment—echoing the now-former U.N. ambassador’s courage and eloquence—and demanded that the women’s conference address women’s needs. “To equate Zionism with colonialism and imperialism,” she objected, “is in a sense to state that the destruction of Israel is a prerequisite for peace.”

Yet Weddington’s arguments were largely ignored by the other delegates, who were more interested in creating a common global agenda of the oppressed. Anti-Zionism was emerging as an identity marker, the glue uniting a broad, diverse, often contradictory left-wing movement. “The real test of our fabled ‘Jewish power’ is how powerless Jews were in Copenhagen,” the radical writer Ellen Willis of the Village Voice glumly reported. A liberal “Diaspora Jew” uninterested in Jewish nationalism, Willis strongly opposed Israel’s control of the West Bank. Still, she slammed radical leftists’ collective blind-spot regarding the anti-Semitic impulses triggering their anti-Israel obsession. Eventually, she proclaimed: “I’m an anti-anti-Zionist.”

Meanwhile, American feminists tried liberating the international women’s movement from its anti-Zionist obsession. Some activists, disgusted by Mexico City and Copenhagen, spent years preparing for the July 1985 International Women’s Conference, in Nairobi, Kenya. Applying feminist methods, Pogrebin and Abzug convened Black-Jewish Women’s dialogue groups and tried establishing Palestinian-Jewish dialogues. Emerging from what she called “virtual feminist retirement,” Betty Friedan mobilized Jewish women worldwide to tap the “strength that comes from authentic assertion of one’s own identity, as Jew or woman.”

Women at Nairobi wanted to avoid the politicized ranting about Zionism and talk, Friedan noted, “as feminists about their common women’s problems.” In the middle of yet another dreary debate about Zionism and racism, a French woman began chanting: “The women of the world are watching and waiting.” Others joined in, until the PLO and the Iranian delegates finally relented. Representatives of 157 countries, many teary-eyed, many singing the conference’s unofficial theme song “We are the World, We are the Women,” unanimously adopted a final document with, Betty Friedan exulted, “every reference to Zionism gone.” The first major international movement to declare Zionism to be racism, the women’s movement now became the first to denounce that lie. Six years later, in 1991, the General Assembly repealed its infamous resolution.

Yet, despite the heroic leadership of Friedan and her sisters, what Moynihan called “The Big Red Lie,” which insists that the national conflict between Israelis and Palestinians must be viewed through the distorting, inflammatory anti-Zionist lens of racism, still persists. Despite her victory in Nairobi, Friedan would be devastated to see that the libel she opposed with such courage and strength is now increasingly accepted by leading American feminists like Judith Butler and Alice Walker, who would rather identify with the warped gender politics of Hezbollah and Hamas than with the history and heroes of their own movement.

Adapted from Moynihan’s Moment: America’s Fight against Zionism as Racism, by Gil Troy, with permission of Oxford University Press, all rights reserved.

Professor Gil Troy, a Senior Fellow in Zionist Thought at the JPPI, the global think tank of the Jewish people, is an American presidential historian, and, most recently, the editor of the three-volume set Theodor Herzl: Zionist Writings, the inaugural publication of The Library of the Jewish People.