I love Christmas.

I’m Jewish. But while we don’t celebrate Christmas in our home, we love celebrating it with our friends.

Growing up in Brooklyn, I’d attend Christmas Eve dinner at my best friend Allison’s house year after year. Starting in the sixth grade, I’d join in on the festivities with Allison’s Italian holiday rituals and delicious Italian food traditions.

I waited all year for the tangy seafood salad, the delicate taste of linguini with clam sauce, and the decadence of chicken Parmesan. I indulged in the food cooked by Allison’s grandmother Eleanor, mainly because it was some of the most delicious food I’ve ever eaten. Perhaps the real reason I loved it so much was that coming from a Jewish, kosher-style home, these dishes would never be cooked at our house. The food I grew up eating at home was mostly Middle Eastern cuisine, as my father’s family was from Syria. I loved it (most of the time), but couldn’t wait for my yearly escape into the Gerbino family’s Italian American Christmas feast.

Eleanor truly adored watching me enjoy her cooking. Every year, we’d count the years I’d been attending their Christmas Eve dinners, and I’d joke that while I loved Allison, it was really her grandma’s cooking that kept me coming back. Eleanor wasn’t just the family cook, she was a self-trained chef who was in love with cooking. Without fail, at the beginning of the meal, Eleanor would call me over to the kitchen and show me one Jewish food item she had baked for me. One year it was black-and-white cookies, another it was challah. During the first few years, I’d try and explain that she didn’t need to make me Jewish food that I ate at home all of the time, but after a while I gave up, and just said thank you, and went back to eating my Italian feast. She wanted her cooking to make me feel at home; I wanted her food that I never had a chance to eat at mine.

Courtesy Brianna Gerbino

Our food traditions couldn’t have been more different, except for dessert—when our worlds collided. After the table was cleared of the appetizers, main courses, and multiple side dishes, Eleanor would announce that she was heading to the kitchen to make sfingi—a very simple looking, yet difficult to perfect Italian dessert. We weren’t allowed in or near the kitchen while this was happening, because it required frying, and lots of monitoring. We’d all wait patiently for the sfingi to be scooped out of the fryer, sprinkled with powdered sugar, and served piping hot. And every year, after I took the first bite, I’d say to Eleanor, “This reminds me of a dessert I eat with my family, called sfenj.”

“No, it’s different,” she’d respond. “This is a Sicilian dish my mother, Vita, learned from her mother in Italy.”

I’d usually pipe down, but couldn’t help but think about the similarities between the two desserts. Sfenj, a traditional Moroccan doughnut often eaten during Hanukkah, is made from similar ingredients as Eleanor’s sfingi, with the biggest difference being the Italian version uses dairy—specifically ricotta cheese. But both are spongy doughnuts fried in oil, topped with powdered sugar, served piping hot. Neither is too sweet, and both are addicting.

Years went by, and Eleanor passed away around the same time my father got sick with cancer, and I began a journey to document our family’s food traditions and recipes. It was clear to me that these two dishes—sfingi and sfenj—must have come from a similar place, and had to be related. I had a feeling our food traditions had more in common than we knew, and so I recently set out to investigate.

This year, we’re not able to participate in Allison’s Christmas Eve Italian feast. I felt so sad about it, so I reached out to her family to see if I could try my hand at making Eleanor’s famous sfingi recipe. At the same time, around Hanukkah this year, I started seeing various Middle Eastern chefs talk about sfenj more than I’ve ever noticed before. It reminded me of whenever my father would take us out to eat: If sfenj was on the dessert menu, we’d get it. Now more than ever, whether it’s an alternative to the traditional sufganiyot we eat at Hanukkah, or just a different dessert to add to the rotation, every time I saw this dish and recipe, it made me want to understand its origin, and how (if at all) it’s related to Eleanor’s sfingi.

The first thing I did was interview Allison’s mother, Lorraine (Eleanor’s daughter). At first, we reminisced about Eleanor, and how serious she was about her cooking and baking, rarely allowing anyone to join her in the kitchen. I asked why she thinks Eleanor always made me special Jewish foods on Christmas when all I wanted was her delectable Italian food. “Most years, on Rosh Hashanah, my mom would make a brisket,” said Lorraine. “I’d say, ‘Ma, we’re not even Jewish, we don’t celebrate Rosh Hashanah!’ And she’d respond with, “We don’t need to be Jewish to celebrate holidays, food is food.’ My mother just loved to cook new things, and she didn’t need much of an excuse.”

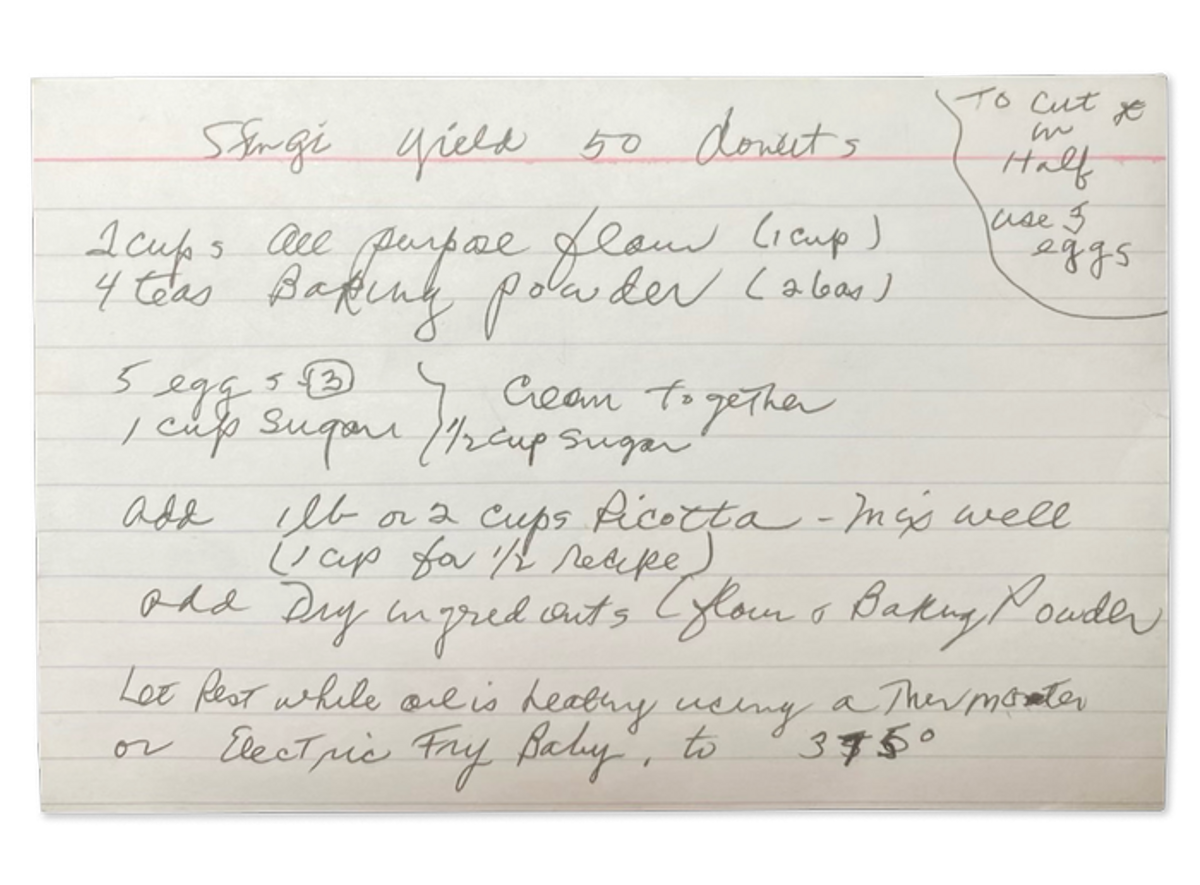

Courtesy the author

We dove into sfingi. Where did it come from? Why did Eleanor only make it on Christmas? The original sfingi recipe, it turns out, originated from Eleanor’s mother, Vita Morrielle. While her family lived in Sicily, her father worked as a seaman, traveling back and forth between Italy and Tunisia. Vita was born in Tunisia, and due to that, their Italian dishes were influenced by Arabic and North African flavors. “Even my mother’s fish sauce had a hint of North African flavors,” said Lorraine. “She’d use pine nuts and raisins, just like many Moroccan dishes use.”

Lorraine never knew why her mother and grandmother would only make sfingi on Christmas Eve. “I don’t remember ever having it any other night of the year,” she said. “And we knew not to even ask for it.”

Lorraine agreed that our dishes sounded too similar to be a coincidence, and led me to her niece Brianna Gerbino. Brianna was always a natural chef, and would often be the only one allowed in the kitchen with her grandmother. Brianna grew up to become a pastry chef, and inherited all of Eleanor’s recipes, and trust in the kitchen.

While Brianna wasn’t any more sure of the origin of the recipe, she was able to tell me why she thinks Eleanor only made this dish sparingly. “Sfingi is probably one of the most difficult recipes I inherited from my grandmother,” said Brianna. “You have to fry them in a portable tabletop fryer, ensuring that they’re perfectly round, and golden brown. If they’re undercooked, they’re mushy inside and you have to start all over again. It takes a lot of practice, and a specific eye to know when they’re ready.” Brianna carries on the tradition of making the sfingi every Christmas, and never any other night.

While Lorraine began to connect the dots for me about how these two dishes with almost the same name—popular around the same time of year—were similar, I wanted to learn more about how. I looked into the various chefs that focus on Moroccan cuisine, and stumbled upon Ron Arazi from New York Shuk, a maker of handcrafted Middle Eastern pantry staples. While I ate many of Arazi’s store-bought spices and sauces, a simple Google search led me to his explanation and recipe for sfenj. “Sfenj are ring-shaped doughnuts that are popular across Morocco, Algeria, and Libya,” writes Arazi on his site, where he also includes a video of how to make them.

I spoke with Arazi to understand a bit more about the tradition of making and eating sfenj. Arazi’s family is originally from Morocco, and from what he learned from his parents and grandparents, Moroccan sfenj was something that you could buy as a breakfast item at various street vendors, but wasn’t something you’d make at home. In Jewish Moroccan cuisine, sfenj evolved to be made a bit sweeter using a coating of sugar or syrup. “Growing up, we would eat it during Hanukkah, or at the Mimouna (a feast after Passover), but we never really made it regularly,” said Arazi. Sfenj is just one of the many food traditions Arazi continues with his own family, and only makes it during Hanukkah. “These doughnuts are something remarkable,” he said. “The shape is amorphous, the texture is chewy, and it really is a very simple recipe.”

On his site, Arazi also notes: “Tunisians also enjoy a closely-related fritter called yoyo.” If Arazi’s sfenj is similar to a Tunisian yoyo, and Allison’s great-grandmother Vita was born in Tunisia, I knew I was on to something.

I reached out to Leah Koenig, who has written about sfenj for Tablet, and recently published Portico: Cooking and Feasting in Rome’s Jewish Kitchen. As it turns out, Koenig has written about this uncanny connection before. “The name for both pastries comes from the Arabic word isfenj, which translates to ‘sponge,’ and refers to the way dough soaks up oil while it fries, and also to its bouncy texture,” writes Koenig. “Interestingly, sufganiyot also means sponge in Hebrew, suggesting a linguistic connection between all three donuts. This connection also hints to the influence that Arabic cuisine had across both North Africa and Southern Italy.”

While I don’t have the exact linkage I was looking for, I am pretty confident Allison’s grandmother’s Christmas sfingi recipe, and the Sephardic sfenj I grew up eating during Hanukkah with my father might have come from the same place. Those similar, but different recipes followed people of a variety of cultures on different paths, across the world from each other for hundreds of years, and landed in the same neighborhood in Brooklyn.

I always knew we were more similar than different.

Jamie Betesh Carter is a researcher, writer, and mother living in Brooklyn.