I Am Charlotte’s Tsimmes

As Hadassah publishes a professionally made cookbook on its 100th anniversary, its archive reveals snapshots of changing Jewish American life, one typed and mimeographed recipe book at a time

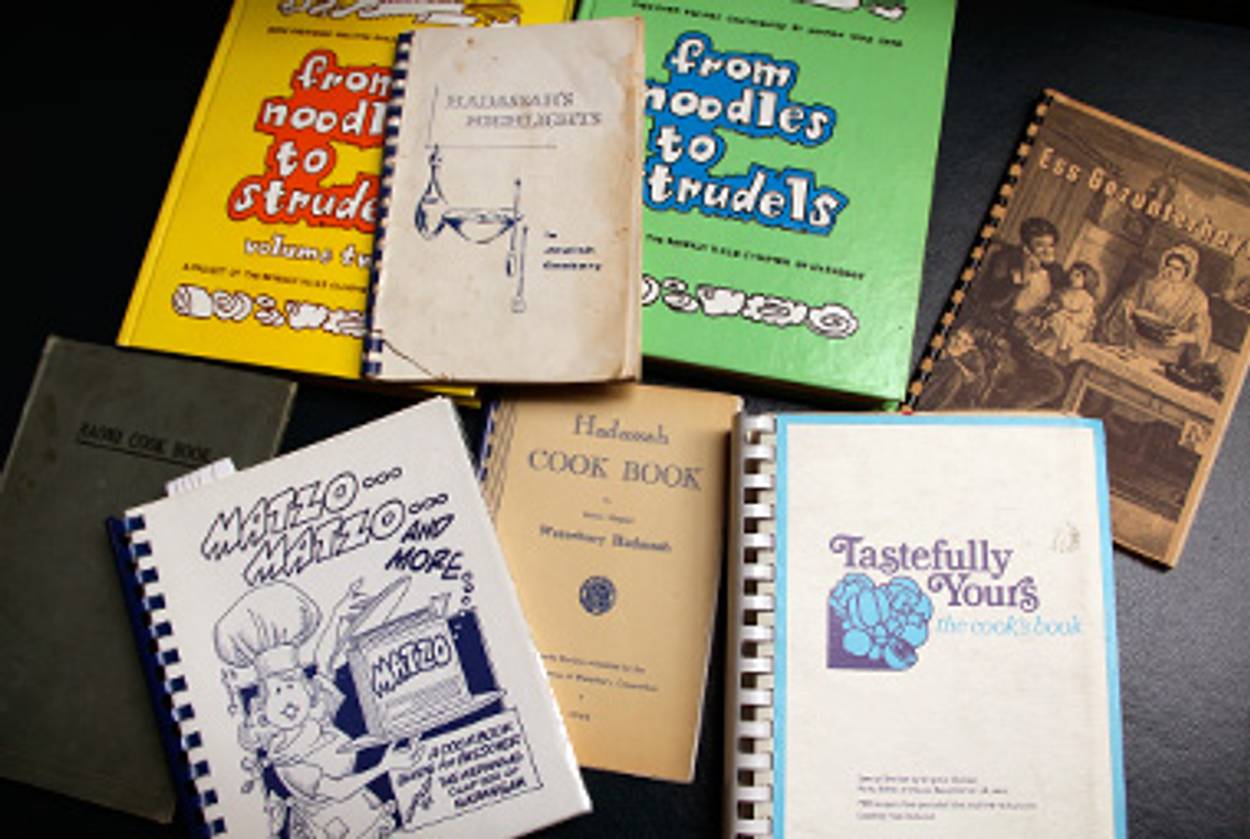

Generations of American Jewish women grew up with Hadassah cookbooks. Plastic-covered and spiral-bound, with recipes contributed by many of our moms, these books were (and still are) produced as fundraisers by regional chapters of the Zionist women’s organization. But now there’s a new Hadassah cookbook, professionally written and edited by the national organization—only the second such cookbook in its history. But the publication of The Hadassah Everyday Cookbook made me want to explore its less-polished predecessors, and so I went to the Center for Jewish History to see what Hadassah’s archive of cookbooks could tell me about the interplay between Jewishness and Americanness, about regional differences, and about what Jewish women were cooking in kitchens from Maine to Oregon and from the 1920s to today.

Susan Woodland, Hadassah’s archivist, pulled out four fat file boxes for me. The Naomi Cook Book, published by Hadassah’s Toronto chapter in 1928, had notes scribbled in Yiddish on its frontispiece and yellowing pages. “Here in this book are the Old and the New,” the introduction promised. “Here are Strudle [sic] and, in the same breath, ice box cakes. Here, the homely dishes that Sarah must have prepared for angels, and here, too, the things that angels upon earth may prepare for modern and critical husbands.”

That definition of “modern” was different from today’s. (Critical husbands, on the other hand, never change.) There are recipes for stewed lung, potted steak, steamed suet pudding, and sago pudding (which Google tells me is like tapioca but made from palm stems instead of cassava root). Then there’s the recipe for kosher soap, which mixes lamb fat and lye or potash, with a warning: “Dissolve in front of open window. This mixture is strong and hard on the eyes.” Cooking times and temperatures are rarely spelled out (“bake in a moderate oven until done”). But there are familiar offerings like “cheese creplach” and pickles, and the book’s aim was similar to that of many cookbooks today. It promised to be “practical in the last degree”—which, it points out, is as it should be, as “funds raised by the sale of this book will be employed in the immensely practical work of Hadassah in Palestine.”

Some cookbooks reveal the effort that went into kosher cooking. The Waterbury, Conn., chapter’s 1946 cookbook’s “Rules for Kashering” section discusses the removal of hooves and claws, the positioning of the salting board, and how to remove veins from milt (spleen), and porge the hindquarters—cutting away the forbidden caul, veins, and sinew. There are instructions for yanking branched veins out of poultry and using eggs found inside chickens, with and without shells. But there are also culinary shortcuts, like “mock cheese blintzes,” which involve spreading saltines with cream cheese, dipping them into beaten egg and frying them in butter. There’s the familiar “Luxen Coogle,” plus New England staples like Grapenut pudding, which was one of my favorites when I was growing up in nearby Rhode Island several decades later.

It’s fun to see how the books mix contemporary culinary trends with Jewish culture. The Ess Gezunterhayt cookbook produced by the Greenwich, Conn., chapter (undated, but an inscription that says “Many of these recipes are as old as our Jewish tradition, and many are as new as the State of Israel” hints that it’s from the late 1940s or early 1950s) offers “cocktail franks” (frankfurters cut up and simmered in a mixture of currant jelly and mustard) and “mock gefilte fish” made with canned tuna. The book’s glossary combines then-trendy cooking terms like “au gratin” and “baba” with Ashkenazi ones like “farfel,” “fleishig” and “holishkes” (stuffed cabbage). On the last page, there is an ad: “A Friend of Hadassah, long and true, as your Tupperware dealer she’ll always serve you!”

Some of the Southern cookbooks are notable for being glatt trayf. Tastefully Yours: The Cook’s Book, from Roanoake, Va., published in 1969, offers recipes for crab and lobster bisque, oysters casino, and shrimp casserole. Recipes like herring cacciatore are an unholy mix of Jewish and goyish. There’s no mention of the word “Hadassah” or “Jewish” on the cover. Tastefully Yours proudly presents recipes from then-fancy restaurants like Sardi’s and Romeo Salta in New York, the Greenbrier in West Virginia, and the Gourmet at Crossroads Mall—“the superlative restaurant in Roanoke.” In a true Southern touch, there’s even a Robert E. Lee poundcake. A multipage insert by Virginia Stanton, a famous mid-century hostess and “party editor” of House Beautiful magazine, explains in detail how to cook veggies using techniques that were, at the time, ground-breaking, such as steaming or sautéing. “The Orientals,” Stanton informs her readers, “all cook their vegetables very lightly and their thin slices and crunchiness are a delight.”

In the books, brand names that are now lost to the mists of time reappear over and over. What were Chef Howald’s seasoning, Mei Yen powder, Purity flour? Sour cream, pimentos, cream cheese, and French onion soup mix gradually give way to lighter dishes and multicultural offerings. For examples, for decades “Hawaiian” and “Polynesian” were as exotic as it got and meant dumping a can of pineapple chunks on top of the dish. From mid-century on, gelatin salads bloomed like rainbow-colored mushrooms after a rain.

Reading From Noodles to Strudels: Cherished Recipes Contributed by Women Who Care, a 1972 book from Beverly Hills, Calif., one sees feminism coming into the authors’ lives. “While other women are demonstrating, Hadassah women are doing,” the book says pointedly. There’s “Carrot Tsimmes (like Daddy used to make)” and “No-Bake Fruitcake (for the liberated woman),” although the combination of evaporated milk, marshmallows, oil, graham crackers, cloves, mixed candied fruit, and candied orange peel makes liberation sound about as appetizing as the patriarchy. There are lots of potato-chip-and-casserole recipes, along with doctored cake mixes, an acknowledgment that sometimes one wants to get out of the kitchen. But sometimes one wants to wow guests, too, and for that there is “Epicurean Melange,” a kosher gourmet wedding appetizer involving brains, sweetbreads, and non-dairy creamer.

Volume 2 of From Noodles to Studels arrived eight years later, in 1980 and in a world changing faster than ever. “Most Beverly Hills Hadassah kitchens have food processors,” the editors noted. “Chores that were too time consuming for busy volunteers can now be done in seconds by a machine. We have added the wok to our arsenal to fight skyrocketing prices of food. We’ve discovered how far a chicken and a little beef will stretch, blended with the exotic spices of the East. We have become health conscious, cutting down on sugars, salt and eggs and reading labels carefully.” But one thing stays the same: “Though we have borrowed something from cuisines of many lands, our favorites are our Jewish recipes. These treasures are a link in the chain of our own heritage from mother to daughter and will always identify a Jewish table and the Baleboosteh who manages a Jewish home.” (The editors do feel obliged to define baleboosteh as an excellent and praiseworthy homemaker. They could no longer assume that readers understand Yiddish.) The Beverly Hills books offer intriguing dishes like Moroccan b’stilla (the editors patiently explain what cilantro is), Hungarian lamb chardash, sikbaj stew from North Africa, and a selection of harosets from different countries.

It’s fun to see cookbooks that have obviously been used, with stains and margin notes and editorializing by each book’s owner. A recipe in the second Beverly Hills book has been vigorously crossed out, with “NO, UGH” written in huge letters next to it in perfect Parker penmanship. (Given that the recipe includes frozen carrots, dried apricots, brown sugar and a giant can of apricot nectar, it’s no wonder. Hello, diabetic coma.) Who were these women? What role did Judaism and Hadassah play in their lives? Did they love to cook? Did they feel trapped in the kitchen? A little bit of both?

And what does a Hadassah cookbook look like today? Leah Koenig, the current book’s author, strove to create a home-cook-friendly book that would work for a wide variety of lives. “It’s called The Hadassah Everyday Cookbook, but there isn’t one ‘everyday’,” she said. “For a new mom, it can mean ‘l barely have the energy to open a package of fishsticks.’ For the empty nester, there may be more time to go to market and try more elaborate recipes. There’s the college kid. There are men who love to grill. I wanted the book to have something for everyone, to be more representative of who we are as a larger community. Some of the recipes you can make in 30 minutes, and there’s a polenta dish that literally comes together in 10.”

Koenig wants cooking to be joyful. “There’s this attitude that you’re not supposed to enjoy everyday cooking,” she said. “You’re just supposed to grimly get things on the table, and I hate that. That goes against Jewish cooking, the notion of cooking for love and for family. I think the book has a good balance between getting it done and making it fun.”

A food columnist for the Forward and a writer for many food magazines, Koenig didn’t want to duplicate The Hadassah Jewish Holiday Cookbook, the 2002 publication that was the national organization’s first foray into the field. “I didn’t include any recipes for brisket or kugel, because to me those are holiday recipes, not everyday recipes,” she said. “Instead, I tried to think about ingredients that felt Jewish—tahini paste and Middle Eastern stuff, biblical stuff like dates and pomegranates, Ashkenazi things like pickles and rye bread. The granola, for instance, is fantastic; it’s from Not Derby Pie blogger Rivka Friedman. It has tahini and maple syrup as the binder, and, trust me, it’s amazing. I also took traditional Jewish recipes and tweaked them to fit our palate. I have a recipe for grilled tsimmes—I love traditional tsimmes, but I know a lot of people find it too cloying and sweet. So, I grilled sweet potatoes, carrots, fresh apricots and pears and drizzled them with a brown sugar vinaigrette. Plus a lot of the recipes are straight-up Sephardic, because Sephardic food relies on olive oil and fresh veggies; it fits more with healthy contemporary food today.”

The book doesn’t presume a lot of culinary knowledge, the way the early “cook on medium fire until thick” books do. “There isn’t so much learning at your mother’s knee nowadays,” Koenig says. “Now I guess we learn at the knee of the Food Network.” Still, Koenig wants to honor the legacy of Hadassah regional cookbooks. “Every cookbook is kind of a snapshot in time, and I want my cookbook to do that for today,” she says. “I want to be part of this chain while bringing in a newer, broader audience.”

From Naomi Cook Book (1928), Toronto chapter:

Sago Cream Pudding

2 tablespoons sago

1 pint milk

A pinch of salt

2 eggs

½ teaspoon vanilla

¼ cup sugar

1. Wash sago. Scald milk.

2. Add sago and let cook on slow fire until sago is soft and forms a thick mixture.

3. Cream yolks and sugar well, and add slowly to sago. Cook a few minutes longer, add vanilla and remove from stove.

4. Fold sago gradually into stiffly beaten egg whites. Serve cold.

Graham Wafer and Apple Pudding

1 ½ lbs graham wafers

½ peck apples (approximately 5 lbs)

½ pound butter

The juice of 1 lemon

Sugar to taste

1. Roll wafers into fine crumbs. Melt butter and rub into crumbs.

2. Spread half of mixture into baking pan. Boil apples for applesauce, using very little water. Add lemon juice.

3. Spread applesauce on crumb mixture, then cover with balance of crumbs.

4. Bake in moderate oven until brown, about 20 minutes.

From Ess Gezunterhayt (late ‘40s or early ‘50s), Greenwich Connecticut chapter:

Mrs. L Coles’ Norway Spread from Mrs. David Resnick

1 can boneless sardines

1 teaspoon lemon juice

1/3 cup sour cream

2 tablespoons prepared mustard

½ cup mayonnaise or salad dressing

¼ cup chopped celery.

1. Drain sardines and chop fine. Mix with remaining ingredients. Serve with crackers, Melba toast or potato chips.

From Hadassah Gives a Party (1974), Portland, Ore., chapter:

Portland Mist

1 pint bourbon

1 quart black coffee (double strength)

1 pint bulk ice cream or sherbert

1 quart brick vanilla ice cream or sherbet

1. Chill coffee and add bourbon. Mix well.

2. Pour carefully over quart brick ice cream placed in punch bowl.

3. Scoop ice cream pint or sherbet into balls and place around top of bowl.

Serves 30

From The Hadassah Everyday Cookbook (2011):

Leah Koenig singled this out as one of her favorite recipes in the book.

Shakshuka

Serves 2-3

2 tablespoons olive oil

1 small onion, chopped

1 red pepper, seeded and chopped

1 28-ounce can whole, peeled plum tomatoes

5 cloves garlic, diced

2 teaspoons salt

1 teaspoon paprika

1/8 teaspoon cayenne powder

2 heaping teaspoons tomato paste

¼ cup vegetable oil

4-6 large eggs

Red pepper flakes and za’atar for garnish (optional)

1. Heat oil in a 12-inch sauté pan or cast-iron skillet. Add onions and pepper and sauté until softened, about 6 minutes.

2. Pour tomatoes and juice into a bowl and squeeze gently with your hands to break them up. Add crushed tomatoes (with juice) to the pan along with garlic, salt, paprika, cayenne powder, tomato paste and vegetable oil; cover. Bring to a simmer, uncovered and stir occasionally until mixture thickens slightly, 25-30 minutes.

3. Break desired number of eggs directly into pan, over the tomatoes. Cover and continue to cook until eggs are set, 5-6 minutes, carefully basting the eggs once or twice with sauce. Serve hot, sprinkled with red pepper flakes and za’atar, if desired.

Marjorie Ingall is a columnist for Tablet Magazine, and author of Mamaleh Knows Best: What Jewish Mothers Do to Raise Successful, Creative, Empathetic, Independent Children.

Marjorie Ingall is a former columnist for Tablet, the author of Mamaleh Knows Best, and a frequent contributor to the New York Times Book Review.